Abstract

Dietary intolerances to fructose, fructans and FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols) are common, yet poorly recognized and managed. Over the last decade, they have come to the forefront because of new knowledge on the mechanisms and treatment of these conditions. Patients with these problems often present with unexplained bloating, belching, distension, gas, abdominal pain, or diarrhea. Here, we have examined the most up-to-date research on these food-related intolerances, discussed controversies, and have provided some guidelines for the dietary management of these conditions. Breath testing for carbohydrate intolerance appears to be standardized and essential for the diagnosis and management of these conditions, especially in the Western population. While current research shows that the FODMAP diet may be effective in treating some patients with irritable bowel syndrome, additional research is needed to identify more foods items that are high in FODMAPs, and to assess the long-term efficacy and safety of dietary interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Malabsorption and intolerance to carbohydrates are common problems that are frequently encountered in the gastrointestinal (GI) and primary care clinics, but are poorly recognized and managed. Their exact prevalence is unknown. These intolerances frequently lead to unexplained GI symptoms such as abdominal bloating, gas, flatulence, pain, distension, nausea, and diarrhea. Often, patients with such GI symptoms, and especially those with alarm symptoms, will undergo investigations to rule out organic disorders that may include endoscopy, imaging studies, and blood and stool tests. When these tests are negative, then they are likely to have functional GI disorders that may include functional dyspepsia, functional bloating, and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), etc., which frequently overlap.

IBS is estimated to affect 5–30 % of the world’s population and approximately 10–15 % of the population in the US [1]. Research suggests that these disorders have a negative impact on the quality of life to a similar extent to chronic diseases including gastroesophageal reflux disease or asthma [2]. Self-reported food intolerance among subjects with high symptom burden has a great negative impact on their quality of life [3•]. Approximately 60–80 % of patients with IBS believe that their symptoms are diet-related, of which three-quarters is related to incompletely absorbed carbohydrates [3•, 4]. In addition, the advice patients receive regarding diet varies enormously. Thus, there is a large unmet need for a clear diagnosis of the underlying problem(s) as well as consistent and effective advice on dietary treatments.

In this review, we focus on dietary fructose and fructan intolerances, both of which have been poorly recognized until recently, and also discuss the role of dietary interventions including low FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols) in patients with unexplained GI symptoms.

Fructose Intolerance

Fructose is a 6-carbon monosaccharide molecule that is naturally present in a variety of foods. Foods high in fructose can include certain fruits, vegetables, and honey but it is also produced enzymatically from corn as high fructose corn syrup (HFCS), which is commonly found in many food sweeteners and soft drinks (Table 1). According to the US Department of Agriculture (USDA), HFCS consumption has increased by more than 1,000 % between 1970 and 1990 [5], with an annual consumption of fructose that has risen from less than a ton in 1966 to 8.8 million tons in 2003 [6]. It is possible that a rise in fructose consumption in the US population has resulted in a rise in fructose malabsorption and intolerance [7]. Both conditions are pretty much often unrecognized, and this has resulted in mislabeling of many patients as having IBS especially in those with diarrhea-predominant symptoms. One study has estimated that up to one-third of patients with suspected IBS had fructose malabsorption and dietary fructose intolerance (DFI) [8••].

Humans have a limited absorptive capacity for fructose since its absorption is an energy-independent process and this capacity is quite variable [9, 10]. While glucose is completely absorbed through an active transport mechanism in the small intestine that is facilitated by GLUT-2 and GLUT-5 transporters, fructose is mainly absorbed through carrier-mediated facilitative diffusion and GLUT-5 [10, 11]. A recent study did not show a difference in expression of GLUT-2/-5 transporters in a small number of patients with DFI versus controls [9]. This suggests that other transporters may be involved as indicated in animal studies with GLUT-8 [12], but confirmation in human studies is needed. Malabsorption of fructose generates an osmotic force which increases water influx into the lumen and then leads to rapid propulsion of bowel contents into the colon, where it is fermented, leading to the production of gas [13]. This can result in symptoms including abdominal pain, excessive gas, and bloating, especially in patients with visceral hypersensitivity [11].

Breath Testing and Diagnosis of Fructose Intolerance

It is important to consider small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) as a cause of unexplained GI symptoms, and especially when breath tests for hydrogen (H2) and methane (CH4) are positive with glucose and fructose (in the diabetic population). A discussion on SIBO is beyond the scope of this review, but if found this should be treated with antibiotics before considering fructose intolerance.

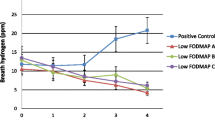

Breath testing after ingestion of fructose has been widely adopted as a standard method of identifying fructose malabsorption and intolerance. A dose of 25 g of fructose dissolved in a 10 % solution is generally accepted as the appropriate dose of fructose for clinical use of H2 and CH4 breath testing [14••]. A study that compared 3 doses of fructose (15, 25, and 50 g) found that 100 % of healthy volunteers could absorb 15 g of fructose, 90 % could absorb 25 g of fructose, but only 20–30 % could absorb 50 g [14••]. In pediatrics, appropriate dosage still requires standardization, but a dose of 0.5–1 g/kg with a maximal dose of 10–15 g has been suggested [15]. These tests are by no means perfect, but are the best available tools for diagnosis of fructose intolerance. Presence of malabsorption and reproduction of symptoms during a breath test provides the best objective evidence and symptom correlation for fructose intolerance that can then lead to a firm diagnosis, and this helps avoid the use of empirical or unnecessarily restrictive diets. An example of a positive fructose breath test is shown in Fig. 1.

During testing, both H2 and CH4 should be analyzed from the breath samples that are collected every 30 min for up to 3 h. A rise in 5 ppm over 3 consecutive measurements or ≥20 ppm H2 or ≥10 ppm CH4 or ≥15 ppm H2 and CH4 rise above baseline is regarded as a positive test [14••]. One issue associated with this testing is the interpretation of symptoms, which do not appear to correlate with rises in H2. Some practitioners use a lack of symptoms during testing as a rational to exclude fructose intolerance despite significant increases in breath H2 [16, 17], while others disagree. Symptoms may also lag somewhat. For example, a patient may experience symptoms only after testing has ended. These episodes could be related to delayed intestinal transit and should be considered in the interpretation of test results. Patients who experience otherwise unexplained symptoms such as diarrhea or bloating during testing but do not show rises in H2 are also considered to have fructose malabsorption. In such individuals, there is a rapid influx of fluid into the lumen and rapid transport of highly osmotic and unabsorbed fructose across the colon. Consequently, there is less time available for gas production from the fermentation of fructose. Patients are often interested in knowing whether their breath test can identify if they have mild or severe intolerance. Unfortunately, there is a lack of studies to support such a categorization in the literature [16, 17].

Dietary Treatment for Fructose Intolerance

Published guidelines for fructose intolerance from the American Dietetic Association (now the Academy for Nutrition and Dietetics) include foods with less than 3 g of fructose per serving, less than 0.5 g of free fructose (defined as fructose in excess of glucose) per 100 g of food, and less than 0.5 g of fructan per serving, but these guidelines are only arbitrary cut-off values [13]. It is proposed that it is the free fructose which most strongly influences fructose malabsorption, though a meal with high total fructose content could also result in symptoms. In one study that tested these dietary recommendations, 77 % of the 62 patients with IBS were considered adherent to the diet, while 74 % of all patients responded favorably to all abdominal symptoms [18]. Interestingly, 15 % of these patients used supplemental glucose to balance free fructose in their diets and all reported that they were symptom-free with this strategy [18]. Another study which examined this phenomenon found that when subjects consumed 50 g of free fructose, breath H2 levels were four times higher when compared to subjects who consumed 50 g of fructose in the form of sucrose [19].

Patient compliance with fructose restricted diet was found in slightly more than half of study participants, as shown by Choi et al., and in the compliant group, significant improvements were seen in belching, bloating, and abdominal pain as well as in all other symptoms at 1 year [8••]. Despite having mild to moderate impact on their quality of life, all the adherent patients planned to continue the dietary restriction even after study completion [8••]. Another study similarly reported significant improvement in symptoms but a lesser impact on lifestyle with restriction of both fructose and fructans in a group of IBS patients with DFI [18].

There are empirical protocols or guidelines in the dietary management of fructose malabsorption or intolerance, and therefore management depends on the center’s experience. At our center, patients with fructose intolerance will undergo, firstly, the “elimination phase”, where patients are encouraged to follow a diet with approximately 5 g of fructose per day for about 2 weeks (a totally fructose-free diet is cumbersome and not usually required). Once patients experience sufficient relief from their intolerance symptoms (usually in 2–6 weeks), they are then encouraged to start a “re-introduction phase”, during which they reinstate small amounts of slightly higher fructose-containing foods, one at a time, in order to determine exactly how much fructose they can personally tolerate, and have a diet that is the least restrictive as possible while still keeping their symptoms under control. The lists of foods that we advise patients to consume and avoid during the elimination and reintroduction phase are found in Table 1. Typically, patients can tolerate 10–15 g of fructose per day.

Alternative Treatments

While lactase enzyme tablets are available to help people digest products containing lactose, there is a dearth of such enzyme-based treatments for dietary fructose intolerance. One cross-over study reported the use of xylose isomerase (fructosin, which converts fructose to glucose) as an alternative therapy for fructose intolerance. While this product did lead to significant decreases in H2 excretion (but not elimination of H2, while CH4 was not measured), as well as symptoms such as nausea and abdominal pain, it did not reduce bloating [20]. Furthermore, 30 % of patients receiving isomerase or placebo showed no rise in H2, which suggests that some of the subjects may not have been truly fructose-intolerant [20]. More research is needed to determine if this compound or others would be an effective treatment for those with fructose intolerance.

Fructan Intolerance

Fructans are oligo- or polysaccharides that include short chains of fructose units with a terminal glucose molecule. Fructans with a 2–9 unit length are referred to as oligofructose and those with >10 units as inulins [21]. The most common structural forms of fructan are inulin, levanare, and geraminan. The human body has limited ability to break down these oligo- or polysaccharides in the small bowel and only absorbs 5–15 % of fructan [22, 23•]. The mechanism for malabsorption and intolerance is related to the lack of enzymes to fully hydrolyze glycosidic linkages of this complex polysaccharide, and the malabsorbed fructans when delivered to the colon, are then fermented causing symptoms [24]. Furthermore, the small molecule of fructans draws more water into the intestine which can result in bloating and diarrhea [24].

The USDA 1994-1996 Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals showed that the average fructan consumption in the US population was 3.91 g/day [25], but in other populations it may vary between 1 and 20 g [18]. The consumption rate is believed to have increased further by now since fructan-containing diets are very common in the Western diet, as more wheat-based products (breakfast cereals, pasta, and bread) are consumed, but further epidemiological data are needed. Many foods are high in fructans and examples are shown in Table 2. Although the fructose and fructan content of different foods has been estimated [25, 26], additional research is needed on a wider range of newly-introduced items, especially inulin-based, in the market. Also, the effect of food preparation and cooking on foods containing fructan is unknown and needs to be examined.

No Standardized Test but Breath Testing is a Possibility

At the moment, there is no standardized test for a diagnosis of fructan intolerance. There are only a few studies on absorptive capacity of fructan in humans [27, 28]. A preliminary report suggests that a dose of 10 g may be the optimal dose for breath testing of up to 3 h in suspected fructan intolerance [23•]. In this dose-ranging response study, 14 healthy subjects, in a random order, were subjected to 7.5, 10, or 12.5 g of 10 % fructan (chicory inulin) solution at weekly intervals. Breath samples were collected and assessed for H2 and CH4 every 30 min for 5 h. It was found that the amount of H2 and CH4 production correlated with the dose of ingested fructan and peak by around 4 h. A composite index, the Fructan Intolerance Index (FII), which is a change of ≥20 ppm over baseline of H2 and or CH4 along with abdominal symptoms during the test, was found to best characterize fructan intolerance. More studies are needed to confirm the utility of this test in clinical practice.

Dietary Management of Fructan Intolerance

Restricting fructan in dietary intake may reduce symptoms in a variety of GI disorders [16]. It has been estimated that 24 % of IBS patients may be sensitive to fructans [3•]. In one study, restriction of fructan and fructose in the diet was found to reduce symptoms in patients with IBS [27]. The only study to look at fructan independently of other FODMAPs, found that patients with unexplained GI symptoms and who were negative for bacterial overgrowth, fructose intolerance, and lactose intolerance showed a significant malabsorption of fructans and were symptomatic during testing indicating intolerance [28]. Clearly, more robust evidence is needed to demonstrate the benefits of fructan restriction in functional GI disorders.

There are no clear guidelines on dietary management in fructan intolerance since there are no robust published data. As with other carbohydrate intolerance, identification and elimination of problematic foods containing fructan is the principle approach. The list in Table 2 is by no means exhaustive since more fructan-containing foods have been introduced recently into the market. Furthermore, foods containing higher unit length of fructans (for example rye) may be better tolerated but on the other hand, restricting galactans (for example raffinose and stacchyose) may be difficult with vegetarians. In any case, involvement of an interested dietitian is paramount.

What Are Fodmaps? Is It Just Hype?

FODMAPs are a group of short-chain carbohydrates which are poorly absorbed in the GI tract. A list of high FODMAP foods is shown in Table 2. The monosaccharide, fructose, and oligosaccharide, fructan, as discussed above are all part of FODMAPs. The disaccharide lactose is found in a variety of dairy products. Polyols are sugar alcohols found in certain fruits including peaches and plums. Sugar alcohols such as sorbitol, lactitol, and xylitol are also commonly found in sugar-free products [29]. At least 70 % of polyols are not absorbed in healthy individuals [29]. These highly osmotic substances are rapidly fermented by bacteria. FODMAPs may induce GI symptoms via immune-mediated pathways, luminal distension, or through direct action of the FODMAPs themselves [30••]. Many patients with IBS have visceral hypersensitivity, which could be triggered by abrupt luminal distension [30••]. FODMAPs have an additive effect on symptoms in patients with IBS [19, 31] and, therefore, total FODMAPs intake becomes important. However, some people may be more sensitive to some groups of FODMAPs than others. A study by Böhn et al. examined self-reported dietary intolerances in IBS and found that 70 % of surveyed patients reported sensitivity to foods high in FODMAPs, 49 % reported sensitivity to dairy products (high in lactose), 36 % to beans (galactans), and 23 % to plums (fructose + polyols) [3•]. The low FODMAPs diet was developed in 2001 to help treat functional gut disorders, but its efficacy and safety remains controversial.

Efficacy of Low FODMAPs Diet

Recent evidence suggests that the low FODMAPs diet appears to be efficacious in improving symptoms in patients with unexplained GI symptoms. The key principle for its success is dietary education. Whilst effective short term, there are practical hurdles regarding such education, and its long-term safety or efficacy is not yet known.

A low FODMAP diet in IBS was shown in a study to be more effective than dietary guidelines [32]. A RCT also showed greater effectiveness of low FODMAPs compared to habitual diet in improving IBS symptoms [33]. Similarly, a recent single blinded RCT showed its efficacy in IBS [34•]. A summary of these published studies are shown in Table 3. To conclude, there is significant disparity in subject selection, dietary interventions, and outcome assessments in most of these studies, and hence definitive conclusions on efficacy of low FODMAPs diet cannot yet be made.

Besides functional diseases, some studies suggest that patients with IBD or patients with an ileostomy may also benefit from a low FODMAP diet. It is also possible that the FODMAP content of food may be linked to diarrhea seen in patients receiving enteral nutrition [36, 37], but more studies are needed despite recent reviews supporting this form of dietary management [38].

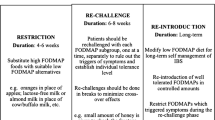

Dietary Guidelines for the Low FODMAPs Diet

Although patients often observe some improvement in symptoms within the first week, usually there is progressive increase in efficacy over the first 6 weeks; hence, it is recommended that patients who benefit from the diet, strictly adhere for at least 6–8 weeks. Following this period of elimination, patients are encouraged to “challenge” themselves with different groups of FODMAPs, in order to determine to which group(s) of FODMAPs they are sensitive, and then to liberalize the diet as much as possible [29]. The challenge phase can be done either by adding foods high in a particular group of FODMAPs for a day, or by starting with a very small amount of FODMAPs from one group and gradually adding more items into the diet in order to determine the individual tolerance. Most seem to favor the more cautious approach. If there is little efficacy after 8 weeks of elimination, the diet may be discontinued. However, some people who report inadequate symptom improvement with the diet still report that their symptoms are aggravated when they eat high FODMAP foods [29].

Patients on the low FODMAP diet were found to have altered starch, total sugar, carbohydrates, and calcium intake [32]. Also, fiber intake can sometimes be of concern to some patients. Whole grain gluten-free breads, other wheat-free whole grains such as brown rice, and the inclusion of low FODMAP fruits and vegetables are all encouraged to offset that potential low fiber intake [29]. More studies are needed to determine the nutritional adequacy of the diet. It is also unknown whether the change in prebiotic intake in the FODMAP diet could have any negative effects on the intestinal microbiome, or whether the associated changes in the gut microenvironment could affect health. It appears that it is safe to follow the diet as long as necessary with the assistance of a dietitian [29], and this approach can also help to increase compliance [39].

Conclusions

Dietary fructose and fructan intolerance are common clinical problems that lead to unexplained GI symptoms. Gastroenterologists and dietitians need to be aware of these conditions and of the tests designed to diagnose these problems. A fructose-restricted diet is an effective treatment option for dietary fructose intolerance, but more studies are needed to examine the long-term efficacy and adherence to such diets. Fructan intolerance is a new concept and warrants further studies. The efficacy of dietary restrictions in fructan intolerance is not known. The low FODMAP diet seems to be useful in controlling IBS symptoms, but more rigorous studies are needed including the FODMAP content of more foods. Tests to determine tolerance to individual FODMAPs may help to liberalize a patient’s diet, though this also calls for additional study.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Hungin AP, Chang L, Locke GR, Dennis EH, Barghout V. Irritable bowel syndrome in the United States: prevalence, symptom patterns and impact. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1365–75.

Chang L. Review article: epidemiology and quality of life in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20 Suppl 7:31–9.

Böhn L, Störsrud S, Törnblom H, Bengtsson U, Simrén M. Self-reported food-related gastrointestinal symptoms of IBS are common and associated with more severe symptoms and reduced quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:634–41. This study investigates dietary food triggers using a food questionnaire in patients with IBS and their effects on gastrointestinal and psychological symptoms and quality of life.

Heizer WD, Southern S, McGovern S. The role of diet in symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in adults: a narrative review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1204–14.

Bray GA, Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity. Am Clin Nutr. 2004;79:537–43.

Economic Research Service, USDA. Table 49–US total estimated deliveries of caloric sweeteners for domestic food and beverage use, by calendar year. 2003.

Choi YK, Johlin Jr FC, Summers RW, Jackson M, Rao SS. Fructose intolerance: an under-recognized problem. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1348–53.

Choi YK, Kraft N, Zimmerman B, Jackson M, Rao SS. Fructose intolerance in IBS and utility of fructose-restricted diet. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:233–8. This study provides evidence that fructose intolerance is prevalent in patients with IBS and showed that, with compliance to fructose-restricted diet, symptoms improved despite only moderate impact on lifestyle.

Wilder-Smith CH, Li X, Ho SSY, Leong SM, Wong RK, Koay ESC, et al. Fructose transporters GLUT5 and GLUT2 expression in adult patients with fructose intolerance. United Eur Gastroenterol J. 2013. doi:10.1177/2050640613505279.

Riby JE, Fujisawa T, Kretchmer N. Fructose absorption. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;58:748S–53S.

Putkonen L, Yao CK, Gibson PR. Fructose malabsorption syndrome. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16:473–7.

DeBosch BJ, Chi M, Moley KH. Glucose transporter 8 (GLUT8) regulates enterocyte fructose transport and global mammalian fructose utilization. Endocrinology. 2012;153:4181–91.

Barrett JS, Gearry RB, Muir JG, Irving PM, Rose R, Rosella O, et al. Dietary poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates increase delivery of water and fermentable substrates to the proximal colon. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:874–82.

Rao SS, Attaluri A, Anderson L, Stumbo P. Ability of the normal human intestine to absorb fructose: evaluation by breath testing. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:959–63. The dose for breath testing of fructose malabsorption is determined in this dose-response study in normal volunteers.

Jones HF, Butler RN, Moore DJ, Brooks DA. Developmental changes and fructose absorption in children: effect on malabsorption testing and dietary management. Nutr Rev. 2013;71:300–9.

Gibson PR, Newnham E, Barrett JS, Shepherd SJ, Muir JG. Review article: fructose malabsorption and the bigger picture. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:349–63.

Barrett JS, Gibson PR. Fructose and lactose testing. Aust Fam Physician. 2012;41:293–6.

Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Fructose malabsorption and symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome: guidelines for effective dietary management. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:1631–9.

Kim Y, Park SC, Wolf BW, Hertzler SR. Combination of erythritol and fructose increases gastrointestinal symptoms in healthy adults. Nutr Res. 2011;31:836–41.

Komericki P, Akkilic-Materna M, Strimitzer T, Weyermair K, Hammer HF, Aberer W. Oral xylose isomerase decreases breath hydrogen excretion and improves gastrointestinal symptoms in fructose malabsorption-a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:980–7.

Roberfroid MB. Introducing inulin-type fructans. Br J Nutr. 2005;93 Suppl 1:S13–25.

Marcason W. What is the FODMAP diet? J Acad Nutr Diet. 2012;112:1696.

Donahue R, Attaluri A, Schneider M, Valestin J, Rao SS. Absorptive capacity of fructans in healthy humans: a dose response study. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:S709. This preliminary study provides the dose appropriate for fructan breath testing.

Muir JG, Shepherd SJ, Rosella O, Rose R, Barrett JS, Gibson PR. Fructan and free fructose content of common Australian vegetables and fruit. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:6619–27.

Moshfegh AJ, Friday JE, Goldman JP, Ahuja JK. Presence of inulin and oligofructose in the diets of Americans. J Nutr. 1999;129:14707S–11S.

Biesiekierski JR, Rosella O, Rose R, Liels K, Barrett JS, Shepherd SJ, et al. Quantification of fructans, galacto-oligosaccharides and other short-chain carbohydrates in processed grains and cereals. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24:154–76.

Shepherd SJ, Parker FC, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Dietary triggers of abdominal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: randomized placebo-controlled evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:765–71.

Attaluri A, Paulson J, Jackson M, Donahue R, Rao SS. Dietary Fructan intolerance: a new recognized problem in IBS. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;57:150.

Barrett JS, Gibson PR. Clinical ramifications of malabsorption of fructose and other short-chain carbohydrates. Pract Gastroenterol. 2007;31:51–65.

Shepherd SJ, Lomer MC, Gibson PR. Short-chain carbohydrates and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:707–17. This review provides comprehensive evaluation of FODMAPs in functional gastrointestinal disorders.

Fernández-Bañares F, Esteve M, Viver JM. Fructose-sorbitol malabsorption. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2009;11:368–74.

Staudacher HM, Whelan K, Irving PM, Lomer MC. Comparison of symptom response following advice for a diet low in fermentable carbohydrates (FODMAPS) versus standard dietary advice in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2011;24:487–95.

de Roest RH, Dobbs BR, Chapman BA, Batman B, O’Brien LA, Leeper JA, et al. The low FODMAP diet improves gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67:895–903.

Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2013;pii: S0016-5085(13):01407–8. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2013.09.046. This randomized controlled trial provides evidence on the efficacy of FODMAPs in IBS.

Ong DK, Mitchell SB, Barrett JS, Shepherd SJ, Irving PM, Biesiekierski JR, et al. Manipulation of dietary short chain carbohydrates alters the pattern of gas production and genesis of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1366–73.

Halmos EP, Muir JG, Barrett JS, Deng M, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Diarrhoea during enteral nutrition is predicted by the poorly absorbed short-chain carbohydrate (FODMAP) content of the formula. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:952–33.

Gearry RB, Irving PM, Barrett JS, Nathan DM, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR. Reduction of dietary poorly absorbed carbohydrates (FODMAPs) improves abdominal symptoms in patients with inflammatory bowel disease-a pilot study. J Crohns Colitis. 2009;3:8–14.

Barrett JS. Expanding our knowledge of fermentable, short-chain carbohydrates for managing gastrointestinal symptoms. Nutr Clin Pract. 2013;28:300–6.

Barrett JS, Gibson PR. Fermentable oligosaccharides disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPS) and nonallergic food intolerance: FODMAPs or food chemicals? Ther Adv Gastroenterol. 2012;5:261–8.

Acknowledgments

We thank Yeong Yeh Lee MD for providing assistance with the manuscript

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest

Satish S. C. Rao declares no conflict of interest. Amy Fedewa is employed by Georgia Regents Medical Center.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does contains studies with human subjects performed by the authors that were approved by ethics boards.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Neurogastroenterology and Motility Disorders of the Gastrointestinal Tract

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fedewa, A., Rao, S.S.C. Dietary Fructose Intolerance, Fructan Intolerance and FODMAPs. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 16, 370 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-013-0370-0

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-013-0370-0