Abstract

Once diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), a woman has a sevenfold increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes relative to women who do not have diabetes during pregnancy. In addition, up to one third of women with GDM have overt diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, or impaired glucose tolerance identified during postpartum glucose screening completed within 6 to 12 weeks. Therefore, the American Diabetes Association, the World Health Organization, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists currently recommend postpartum glucose screening following GDM. However, despite this recommendation, in many settings the majority of women with GDM fail to return for postpartum glucose testing. Studies conducted to date have not comprehensively examined the health care system, the physician, or the patient determinants of successful screening. These studies are required to help develop standard clinical procedures that enable and encourage all women to return for postpartum glucose screening following GDM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

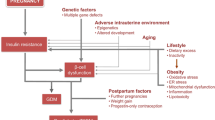

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), defined as glucose intolerance with onset or first recognition during pregnancy, is estimated to affect 2% to 10% of the pregnancies in the United States, with estimates being higher for racial and ethnic minority groups than for non-Hispanic white individuals [1]. Once diagnosed with GDM, a woman has a high chance of developing type 2 diabetes following delivery, with studies estimating cumulative incidence of 15% to 50% [2–9] in the decades following delivery, and a recent meta-analysis reporting a sevenfold increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes in women who had a pregnancy with GDM relative to women who did not have diabetes during pregnancy [4••]. In addition, recent studies indicate that women with GDM not only have increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes, but have increased cardiometabolic and cardiovascular disease risk [10–12].

Although the majority of women with GDM have normal glucose regulation postpartum, up to one third of women will have overt diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, or impaired glucose tolerance identified during postpartum screening completed within 6 to 12 weeks [9, 13–15]. However, although women are often motivated when pregnant to improve their health and often successfully control their diabetes during pregnancy, in many settings the majority of women with GDM fail to return for postpartum glucose testing despite clinical guidelines recommending such testing [6, 13, 16–24].

The current article outlines clinical guidelines recommending postpartum glucose screening following GDM, reviews current estimates of postpartum glucose screening following GDM including the type of screening used, and discusses factors associated with receiving postpartum glucose screening.

Postpartum and Long-Term Glucose Screening Guidelines

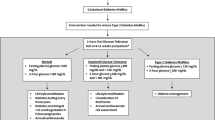

The definitions of diabetes and impaired glucose regulation have changed during the past 15 years, and may change again with the recent emphasis the American Diabetes Association (ADA) has placed on the value of hemoglobin A1c for screening. However, the present review considers the current diagnostic criteria for diabetes, including the 1985 and 1999 World Health Organization (WHO) criteria [25] that require a 2-hour 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) and the 1997 ADA criteria [26] that are based on fasting plasma glucose, but also recognize a casual or 2-hour 75-g OGTT glucose level ≥200 mg/dL as diagnostic of diabetes. Additionally, the ADA in 1997 and the WHO in 1999 focused on impaired glucose tolerance (defined as a 2-hour 75-g OGTT level of 140–199 mg/dL) as a marker of abnormal glucose regulation and increased risk of subsequent type 2 diabetes [25, 26], while more recently the ADA has considered individuals with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose (defined as a fasting plasma glucose 100–125 mg/dL) as being “prediabetic” [27, 28].

Because a fasting plasma glucose test is quicker and easier to perform than a 2-hour 75-g OGTT, but does not identify individuals with impaired glucose tolerance and is therefore less sensitive, there is controversy as to which test should be used to screen individuals at high risk for developing diabetes. Erring on the comprehensive side, the Fifth International Workshop on GDM recommended that all women with GDM undergo a 2-hour 75-g OGTT 6 to 12 weeks postpartum [29]. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Committee on Obstetric Practice and the ADA recommend that all women with GDM be screened at 6 to 12 weeks postpartum with a fasting plasma glucose or a 2-hour 75-g OGTT [30••, 31]. Interestingly, neither ACOG nor ADA clearly states whether the 2-hour 75-g OGTT is preferred over the fasting plasma glucose test. ACOG acknowledges that the 2-hour 75-g OGTT is more sensitive and ADA merely recognizes the 2-hour 75-g OGTT as a valid diagnostic test. The WHO guidelines recommend a 2-hour 75-g OGTT 6 weeks postpartum [25].

Whereas the ACOG does not make a statement about long-term follow-up of women with GDM, the ADA recommends that high-risk individuals, including women with previous GDM, be screened for diabetes every 3 years [31].

Estimates of Postpartum Glucose Screening

A literature search was conducted to identify recently published articles (ie, published since January 1, 2004) specific to postpartum diabetes screening following GDM. A decision was made not to focus on articles in which the primary objective was to determine rates of postpartum type 2 diabetes or abnormal glucose regulation because implementation of these studies likely impacted postpartum screening rates.

During the past 5 years, a number of studies using medical record review were published regarding the prevalence of postpartum glucose screening following GDM [18–24]. These studies are summarized in Table 1. All are retrospective, with the exception of a single study completed using a GDM registry established by Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program in Northern California [20]. The prevalence of postpartum glucose screening with a fasting plasma glucose or a 2-hour 75-g OGTT in these studies ranges from 23% to 58% [18–24]. The two studies reporting the highest prevalence of postpartum glucose screening were the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program in Northern California and the Kaiser Permanente Northwest Health Maintenance Organization in Oregon and Washington State [19, 20]. They were the only studies to report postpartum glucose screening of over 50%. In the single study conducted in Canada, where there is a publically funded universal health care system, the prevalence of postpartum glucose testing was 48% [22].

In addition to the studies completed based on medical record review, three surveys were conducted that collected information on postpartum glucose screening rates following GDM (Table 2) [32–34]. In a survey of ACOG Fellows and Junior Fellows, 74% of physicians who provide prenatal care reported providing postpartum glucose screening following GDM and 58% reported performing a fasting plasma glucose or a 2-hour 75-g OGTT postpartum following GDM [33]. In a second survey of North Carolina in-state practitioners who provided prenatal care, 21%, 43%, 20%, and 16% reported that they always, usually, sometimes, or “rarely or never” screen for abnormal glucose levels following GDM [32]. A total of 54% reported that they used a 2-hour 75-g OGTT when they screened. Interestingly, the survey of North Carolina in-state practitioners was the only study that reported rates of routine screening after the postpartum period; 35% reported that they screen every year, 14% reported that they screen every 3 years, and 47% reported no routine screening [32]. Finally, in a postpartum survey of women with GDM conducted in Australia, 73% of women reported they had received some type of glucose screening at any point postpartum; and 61% reported that they had received some type of screening within the 6- to 8-week window recommended in Australia; however, only 27% reported that they had received a 2-hour 75-g OGTT within the 6- to 8-week postpartum window [34].

Factors Associated with Increased Screening

Successful postpartum glucose screening following GDM is dependent on the health care system, the physician, and the patient. The health care system is responsible for establishing clinical practice recommendations and facilitating their implementation, the physician is responsible for following clinical practice recommendations and ordering the recommended tests, and the patient is responsible for completing the test. Studies conducted to date have not comprehensively examined health care system, physician, or patient determinants of successful screening. However, targeting even a single area may significantly increase postpartum glucose screening following GDM.

In the studies based on medical record review (Table 1), factors consistently associated with increased screening across at least two studies could be grouped into three categories: GDM severity, health care/provider, and patient characteristics. GDM characteristics associated with increased screening included higher GDM diagnostic glucose levels and insulin use to treat diabetes during pregnancy [18, 20, 22, 24]. Health care/provider characteristics associated with increased screening included completion of a 6-week postpartum visit, type of practice site where care was received, having more provider contacts after delivery, and in a single study seeing an endocrinologist after delivery [18–21]. Patient characteristics associated with increased screening included being Asian or Hispanic compared with non-Hispanic white, and lower parity [19, 20, 22].

Factors identified to impact postpartum glucose screening through the two physician surveys were physician age (ie, physicians <40 years of age were more likely to report routine screening), loss to follow-up, patient inconvenience, inconsistent guidelines, patient refusal, patient cost, and reimbursement (Table 2) [32, 33]. Factors identified to impact postpartum glucose screening through the postpartum survey of GDM patients included patient age (ie, younger age was associated with increased screening), written postnatal information, individualized risk reduction advice, receiving care from an endocrinologist among less educated women, and receiving care from a diabetes educator among those who saw an obstetrician (Table 2) [34].

Factors identified to impact postpartum glucose screening in two prospective studies that examined characteristics of women who did and did not return for postpartum glucose screening included patient age, insulin use during pregnancy, GDM diagnostic glucose levels, and prior history of GDM (Table 2) [14, 35]. Interestingly, in contrast to the postpartum survey of women in Australia [34], in the prospective study conducted in Poland [35], older patient age was associated with increased glucose screening. Also interesting, in the study conducted in San Antonio, Texas [14], in which a case manager was used to increase postpartum glucose screening and all patients were encouraged to complete screening, factors associated with increased severity of GDM (ie, higher diagnostic glucose levels, prior history of GDM, and insulin use during pregnancy) were associated with failure to return for postpartum glucose screening.

Finally, in a single randomized clinical trial designed to increase postpartum glucose screening following GDM, postal reminders to patients and their physicians were successfully used as the intervention to improve postpartum glucose screening (Table 2) [36]. A two-by-two factorial design was used: 61% of women completed a 2-hour 75-g OGTT when both the patient and physician received the postal reminder, 55% when only the patient received the postal reminder, 52% when only the physician received the reminder, and only 14% when neither the patient nor the physician received the reminder.

Conclusions

The ADA, the WHO, and the ACOG all currently recommend postpartum glucose screening following GDM [25, 28–30••]. However, there is disagreement over whether an OGTT is required or if obtaining fasting plasma glucose levels is sufficient, as well as what cutpoint should be used to diagnose impaired fasting glucose. These inconsistencies across clinical practice recommendations likely contribute to the observed low postpartum glucose screening rates. However, even in studies aimed at improving postpartum glucose screening rates and in integrated health management organizations with a focus on improving postpartum glucose screening rates, completion rates hovered around 60% [14, 19, 20].

Recently, several clinical trials have indicated that through diet and exercise, or with the aid of a pharmacologic agent, it was possible to lower the incidence or delay the onset of diabetes among individuals at high risk for the disease [37–41]. Thus, the optimum way to reduce the risk associated with diabetes may be preventing diabetes itself, either by altering lifestyle, or by using pharmacologic agents. Women with impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance in the early postpartum period following GDM are at very high risk for developing type 2 diabetes and the burden of diabetes is especially high in these women because of their young age. Reducing the incidence of type 2 diabetes following GDM also reduces the inherent risks to future offspring of exposure to a diabetic intrauterine environment.

Studies conducted to date have not comprehensively examined the health care system, the physician, and the patient determinants of successful screening. For instance, although studies have identified loss to follow-up and failure to return for 6-week postpartum visit as risk factors for failure to complete glucose screening postpartum, studies have not examined what factors facilitate or impede a patient’s ability to return for postpartum medical care. Studies have also not examined to what extent changing from obstetrical to primary care postpartum may impact postpartum glucose screening. Finally, studies have not been completed that focus on long-term screening for diabetes following GDM. These studies are required to help develop standard clinical procedures that enable and encourage all women to return for postpartum glucose screening.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: •• Of major importance

Hunt KJ, Schuller KL: The increasing prevalence of diabetes in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2007, 34:173–199, vii.

Golden SH, Bennett WL, Baptist-Roberts K, et al.: Antepartum glucose tolerance test results as predictors of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Gend Med 2009, 6(Suppl 1):109–122.

Baptiste-Roberts K, Barone BB, Gary TL, et al.: Risk factors for type 2 diabetes among women with gestational diabetes: a systematic review. Am J Med 2009, 122:207–214.e4.

•• Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams D: Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2009, 373:1773–1779. This study is a recent meta-analysis that reports a sevenfold increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes in women who had a pregnancy with GDM relative to women who did not have diabetes during pregnancy.

Kim C, Newton KM, Knopp RH: Gestational diabetes and the incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care 2002, 25:1862–1868.

Kjos SL, Peters RK, Xiang A, et al.: Predicting future diabetes in Latino women with gestational diabetes. Utility of early postpartum glucose tolerance testing. Diabetes 1995, 44:586–591.

Lobner K, Knopff A, Baumgarten A, et al.: Predictors of postpartum diabetes in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 2006, 55:792–797.

Peters RK, Kjos SL, Xiang A, Buchanan TA: Long-term diabetogenic effect of single pregnancy in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus. Lancet 1996, 347:227–230.

Schaefer-Graf UM, Buchanan TA, Xiang AH, Clinical predictors for a high risk for the development of diabetes mellitus in the early puerperium in women with recent gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2002, 186:751–756.

Dawson SI: Glucose tolerance in pregnancy and the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2009, 85:14–19.

Retnakaran R, Qi Y, Connelly PW, et al.: Glucose intolerance in pregnancy and postpartum risk of metabolic syndrome in young women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010, 95:670–677.

Retnakaran R, Shah BR: Mild glucose intolerance in pregnancy and risk of cardiovascular disease: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ 2009, 181:371–376.

Conway DL, Langer O: Effects of new criteria for type 2 diabetes on the rate of postpartum glucose intolerance in women with gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999, 181:610–614.

Hunt KJ, Conway DL: Who returns for postpartum glucose screening following gestational diabetes mellitus? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008, 198:404.e1–404.e6.

Retnakaran R, Qi Y, Sermer M, Connelly PW, et al.: Glucose intolerance in pregnancy and future risk of pre-diabetes or diabetes. Diabetes Care 2008, 31:2026–2031.

Greenberg LR, Moore TR, Murphy H: Gestational diabetes mellitus: antenatal variables as predictors of postpartum glucose intolerance. Obstet Gynecol 1995, 86:97–101.

Kjos SL, Buchanan TA, Greenspoon JS, et al.: Gestational diabetes mellitus: the prevalence of glucose intolerance and diabetes mellitus in the first two months post partum. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990, 163(1 Pt 1):93–98.

Almario CV, Ecker T, Moroz LA, et al.: Obstetricians seldom provide postpartum diabetes screening for women with gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008, 198:528.e1–528.e5.

Dietz PM, Vesco KK, Callaghan WM, et al.: Postpartum screening for diabetes after a gestational diabetes mellitus-affected pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2008, 112:868–874.

Ferrara A, Peng T, Kim C: Trends in postpartum diabetes screening and subsequent diabetes and impaired fasting glucose among women with histories of gestational diabetes mellitus: a report from the Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) Study. Diabetes Care 2009, 32:269–274.

Kim C, Tabaei BP, Burke R, et al.: Missed opportunities for type 2 diabetes mellitus screening among women with a history of gestational diabetes mellitus. Am J Public Health 2006, 96:1643–1648.

Kwong S, Mitchell RS, Senior PA, Chik CL: Postpartum diabetes screening: adherence rate and the performance of fasting plasma glucose versus oral glucose tolerance test. Diabetes Care 2009, 32:2242–2244.

Russell MA, Phipps MG, Olson CL, et al.: Rates of postpartum glucose testing after gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 2006, 108:1456–1462.

Smirnakis KV, Chasan-Taber L, Wolf M, et al.: Postpartum diabetes screening in women with a history of gestational diabetes. Obstet Gynecol 2005, 106:1297–1303.

World Health Organization: Report of a WHO Consultation. Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and its Complications. Part 1: Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Geneva: World Health Organization. Department of Noncommunicable Disease Surveillance; 1999.

Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus [no authors listed]. Diabetes Care 1997, 20:1183–1197.

Genuth S, Alberti KG, Bennett P, et al.: Follow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2003, 26:3160–3167.

American Diabetes Association: Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2009, 32(Suppl 1):S62–S67.

Metzger BE, Buchanan TA, Coustan DR, et al.: Summary and recommendations of the Fifth International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 2007, 30(Suppl 2):S251–S260.

•• Committee on Obstetric Practice: ACOG Committee Opinion No. 435: postpartum screening for abnormal glucose tolerance in women who had gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 2009, 113:1419–1421. This ACOG committee opinion was published following the release of results from the HAPO (Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes) study. HAPO is a large prospective study demonstrating the correlation between increasing hyperglycemia and increased rates of fetal overgrowth.

American Diabetes Association: Standards of medical care in diabetes—2009. Diabetes Care 2009, 32(Suppl 1):S13–S61.

Baker AM, Brody SC, Salisbury K, et al.: Postpartum glucose tolerance screening in women with gestational diabetes in the state of North Carolina. N C Med J 2009, 70:14–19.

Gabbe SG, Gregory RP, Power ML, et al.: Management of diabetes mellitus by obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2004, 103:1229–1234.

Morrison MK, Collins CE, Lowe JM: Postnatal testing for diabetes in Australian women following gestational diabetes mellitus. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2009, 49:494–498.

Ogonowski J, Miazgowski T: The prevalence of 6 weeks postpartum abnormal glucose tolerance in Caucasian women with gestational diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2009, 84:239–244.

Clark HD, Graham ID, Karovitch A, Keely EJ: Do postal reminders increase postpartum screening of diabetes mellitus in women with gestational diabetes mellitus? A randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009, 200:634.e1–634.e7.

Chiasson JL, Josse RG, Gomis R, et al.: Acarbose for prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus: the STOP-NIDDM randomised trial. Lancet 2002, 359:2072–2077.

Gerstein HC, Yusuf S, Bosch J, et al.: Effect of rosiglitazone on the frequency of diabetes in patients with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2006, 368:1096–1105.

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al.: Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002, 346:393–403.

Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, et al.: Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance. The Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care 1997, 20:537–544.

Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, et al.: Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 2001, 344:1343–1350.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Center on Minority and Health Disparities/National Institutes of Health (R01MD004251-02).

Disclosure

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hunt, K.J., Logan, S.L., Conway, D.L. et al. Postpartum Screening Following GDM: How Well Are We Doing?. Curr Diab Rep 10, 235–241 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-010-0110-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-010-0110-x