Abstract

Heart disease remains the leading cause of death in the USA. Overall, heart disease accounts for about 1 in 4 deaths with coronary heart disease (CHD) being responsible for over 370,000 deaths per year. It has frequently and repeatedly been shown that some minority groups in the USA have higher rates of traditional CHD risk factors, different rates of treatment with revascularization procedures, and excess morbidity and mortality from CHD when compared to the non-Hispanic white population. Numerous investigations have been made into the causes of these disparities. This review aims to highlight the recent literature which examines CHD in ethnic minorities and future directions in research and care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Coronary heart disease (CHD) affects 15.5 million Americans with a prevalence of 6.2 % [1]. It has been estimated that CHD is responsible for one in seven deaths in the USA. Disparity between race and ethnic groups has been observed for decades [1]. While hundreds of publications have identified disparities, emphasis is increasing on implementing changes to manifest real-world change [2].

The demographics of the USA are changing rapidly, and the Census Bureau has reported that 44.2 % of the “millennial” generation (born 1982–2000) belongs to a minority group [3]. Additionally, 37.8 % of the current population belongs to non-white minority groups with African-Americans and Hispanics making up the largest proportions, together almost 30 % of the population. Thus, it becomes increasingly important to address the disparities that exist in CHD care from knowledge of the epidemiology to primary prevention and long-term disease management. It is no longer appropriate to assume that large-scale studies performed in a majority white population will be generalizable to our patient population [4•]. This review will highlight recent publications focusing on CHD in the three largest groups of ethnic minorities in the USA: Hispanics/Latinos, African-Americans, and Asian-Americans.

In the 2010 Census, people who identified as Hispanic or Latino comprised 17 % of the US population and had become the largest minority group [5]. Growth is expected to continue, and by 2060, Hispanics will be a larger proportion of the population than African-Americans and Asians combined (Fig. 1). Heart disease is the second leading cause of death for US Hispanics, responsible for 20.8 % of all deaths [7]. In Hispanics older than 65, heart disease takes over as the leading cause and accounts for 26.3 % of deaths. Estimates of mortality of CHD in Hispanics can vary. It has been observed that while the absolute CHD mortality rate is significantly lower in Hispanics when compared to whites, the proportions of total CHD deaths were similar among the two groups due to a lower overall mortality rate in Hispanics [8]. To date, the majority of research involving heart disease in American Hispanics has focused on Mexican subjects [9••]. While Mexican-Americans make up the majority (64.9 %) of the Hispanic population of the USA, the population is diverse with regard to region of origin. This heterogeneity makes it important to pursue additional studies and realize it may not be appropriate to generalize results from Mexicans to all Hispanics. Recently, the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL) has focused on a diverse Hispanic population (Table 2) [10, 15•].

Percentage of total US population by race and ethnicity. Racial groups include only non-Hispanics. Hispanics may be of any race. Source: Projections of the size and composition of the US population: 2014 to 2060 [6]

In 2010, there were 38 million people who identified as non-Hispanic black or African-American. For 2014, this population is estimated to have grown to 39.5 million [5]. Among black males, CHD prevalence is lower than whites (7.2 vs 7.8 %); however, this is reversed in women (7.0 vs 4.6 %) (Table 1). Despite the lower prevalence, death rates from CHD remain higher in blacks than whites [1]. There are many disparities in cardiovascular health between African-Americans and whites including prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, CHD hospitalization rates, CHD revascularization procedures, and life expectancy from CHD [1, 16, 17]. African-Americans have been studied with the aid of several cohorts including the Jackson Heart Study, Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC), Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA), and Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) (Table 2) [11–14].

There were over 15 million Asian-Americans in the 2010 Census. By 2014, this had grown to 17.3 million, making it another expanding subset of the US population [5]. The Census definition of “Asian” includes people who self-identified as Asian, Asian-Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Korea, Japanese, Vietnamese, or Other Asian (examples included Hmong, Laotian, Thai, Pakistani, and Cambodian). The majority of Asians in the USA are foreign-born, totalling 11.6 million in 2011 [5]. Five countries—China, India, South Korea, the Philippines, and Vietnam—have each contributed over a million foreign-born people to the USA. The prevalence of CHD in Asians has been estimated at 3.7 %, lower than the general population [1]. However, the CHD mortality risk is variable with Asian-Indian men and women and Filipino men having greater proportionate mortality burden from CHD [18•].

Cardiovascular Health and CHD Risk Factors

CHD has a significant effect on the Hispanic population with rates similar to or lower than those for the non-Hispanic white population [1, 9••]. Some data point to a health advantage among Hispanics over non-Hispanic populations. Hispanics, despite an increased burden of CHD risk factors and greater socioeconomic disadvantage, are less likely to have CHD and less likely to die from heart disease compared to non-Hispanic whites [8, 19–21]. This discordance comprises the “Hispanic paradox” [22, 23]. This paradox is an important incongruity that remains unresolved. This paradox is not fully defined; it may not apply equally to all Hispanic groups or across all types of heart disease. Concerns about the worse risk factor profile among Hispanics could be falsely allayed by the perception that Hispanics are less susceptible to CHD. Thus, the paradox may confuse CHD risk assessment and lead to delays in interventions in a vulnerable population. The paradox may be untrue and just the effect of Hispanics being a significantly under-studied population in relation to CHD.

The AHA has published the Life’s Simple 7 metrics of cardiovascular health (CVH). One goal of the campaign is to improve different metrics and behaviors. Using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data, social risk factors and non-white race were associated with worse cardiovascular health (fewer ideal metrics) [24]. A similar group of healthy lifestyle factors was evaluated in the ARIC cohort where the prevalence of 5–7 ideal cardiovascular health metrics was 3.6 % for African-American men, 4.2 % for African-American women, 10.5 % for white men, and 18.7 % for white women [25]. Consistent with studies in African-Americans, the prevalence of ideal CVH is lower in Hispanics compared to non-Hispanic whites [26]. In addition to identifying disparity, these studies emphasized that all groups can have lower rates of adverse outcomes if ideal CVH is achieved [27].

Kwagyan examined the effect of participating in a diet-exercise plan on cardiovascular risk factors and CHD risk prediction among obese African-Americans [28]. Five hundred fifteen patients were enrolled in a 6-month program involving a low-salt, low-fat diet and aerobic exercise. The initial 10-year CHD risk, as per the Framingham risk calculator, was 6 % in women and 16 % in men. Following the intervention, the 10-year risk decreased to 4 % in women and 13 % in men. This was accomplished by improvements in BMI (kg/m2), waist circumference, blood pressure, LDL, and HDL. Implementing similar programs that are culturally sensitive across minority groups could significantly improve cardiovascular health and CHD risk for an at-risk population at lower costs than long-term pharmacological treatment.

High serum cholesterol is a known risk factor and a treatment target in primary and secondary prevention of CHD. Using MESA, it has been observed that in a cohort free of CHD, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of dyslipidemia in blacks, Hispanics, and non-Hispanic whites [29]. However, the Hispanic group was 20 % less likely to report drug therapy and the black group 15 % less likely. Furthermore, these groups were 30 % less likely than whites to have their dyslipidemia under control. When these metrics were adjusted for socioeconomic status and health care access, there was attenuation of the disparity, implying that biological differences alone were not responsible for the differences in control.

Lipoprotein(a) (Lp(a)) is a low-density lipoprotein that has been recognized as a risk factor for CHD [30]. Plasma levels vary by race and African-Americans having higher median levels compared to whites [31]. In MESA, it was found that Lp(a) was a predictor of CHD in blacks and whites after stratification [32]. In all race/ethnic groups except Chinese-Americans, using a cutoff of 50 mg/dL was associated with elevated risk. Only in African-Americans, there was still significant detection of risk at a lower cutoff (30 mg/dL).

The HCHS/SOL is a multicenter study with 16,415 Hispanic subjects across the USA [33]. Recently, Daviglus used this cohort to investigate CVD risk factors. In the study, 25.4 % of participants had hypertension with significant variation based on sex and region of origin; 32.6 % of men from the Dominican Republic had hypertension compared to 15.9 % of South American women. Similar variations existed for other risk factors including obesity, cholesterol, diabetes status, and smoking status. It was noted that the most common risk factors for CHD are (in descending order) high cholesterol, obesity, smoking, and hypertension for men and obesity, high cholesterol, and hypertension for women. As HCHS/SOL highlights, there is significant heterogeneity within the Hispanic population and more work is needed to define the burden of CHD risk factors.

Using HCHS/SOL, awareness and treatment of high cholesterol levels was evaluated [34]. The prevalence of high cholesterol was 45 % with 15 % having elevated total cholesterol, 35 % having elevated non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and 37 % having elevated LDL levels. Important to CHD, high cholesterol was found at higher rates in those with hypertension and diabetes and those who were overweight or obese. In those with high cholesterol, 49 % were aware of their diagnosis. Only 30 % of those with high cholesterol, either by previous diagnosis or by blood work done as part of the study, were being treated. The frequency varied but among those younger than 45 years old and eligible for treatment, over 90 % were not being treated. Interesting findings were observed when looking at acculturation factors. Hispanics born in the USA were less likely to be treated for high cholesterol but rates increased in foreign-born individuals with longer residence in the USA. It was also found that control was improved in those with comorbid conditions. This suggests that access to care plays a large part in the under-treatment of the minority population.

Race has been examined independently of socioeconomic and traditional risk factors. Using the MESA population, it was found that own-group neighborhood-level segregation (a measure of an area’s composition being predominantly of one race-ethnic group in comparison to surrounding areas) in African-Americans was associated with a 12 % higher risk of CHD [35•]. The increased risk persisted after controlling for neighborhood, socioeconomic, and patient-level factors. In whites, those who lived in neighborhoods with self-segregation had a 12 % lower risk of CHD; however, these effects were attenuated and the result lost statistical significance after controlling for additional factors. Hispanic own-group neighborhood-level segregation did not impact rates of CHD.

While Asian-Americans are under-studied, national-level surveys have collected data on cardiovascular risk factors. Using NHANES, 25.6 % of Asian adults reported hypertension with increased rates in the older and less educated [36]. Asian men were found to have a higher prevalence of high BMI than women and rates of high HDL five times lower than their female counterparts. High total cholesterol was not associated with sex, age, country of birth, or education level.

Jose used the mortality database from the National Center for Health Statistics and examined 10.4 million records to characterize CHD in multiple Asian-American populations [18•]. CVD mortality was compared between whites and the predominant Asian sub-groups (Asian-Indian, Chinese, Filipino, Japanese, Korean, or Vietnamese). All sub-groups were found to have lower standardized mortality rates than whites. However, when proportionate mortality ratios (PMRs) were used, significant differences emerged. The PMRs for CHD was highest in Asian-Indian men and women and Filipino men. All other sub-groups had lower PMRs when compared to whites. Despite the lower PMRs, many sub-groups did not show the same improvement in mortality over time that was seen in whites. This study is a call to action for more research into the patterns of disease across sub-groups and as an impetus for the US census to expand the traditional race classifications [37].

Coronary Artery Calcium

Coronary artery calcium score (CAC) is a computed tomography-based assessment of calcium deposits in the arteries and is used as a surrogate for CHD. Increasing CAC can be used as a predictor for CHD events [38]. The MESA cohort has produced many studies involving race and CAC. It has been observed that whites of both sexes consistently had a higher likelihood of detectable CAC compared to other race-ethnic groups [38–40]. There were differences in CAC by race which depended on age and gender. In women, Hispanics had the lowest CAC except in the oldest groups where the Chinese subjects had the lowest scores. In men, Hispanics had the second highest percentiles. At younger ages, blacks had the lowest CAC while Chinese were lowest at older age groups. While non-white or non-Hispanic status appeared to be associated with a lower CAC score, the transition from no CAC to new detection of multi-vessel CAC over a 10-year follow-up was more common in African-Americans and Hispanics [41•].

Angina Pectoris and Stable CHD

Using NHANES data from 1988 to 2012, it was found that the number of people reporting symptoms of angina was decreasing over time [42]. Initially, 80 % of those who reported angina were white; however, this had dropped to 59 % by the 2009–2012 surveys. Over the period of the study, rates in non-Hispanic whites decreased by a third while remaining relatively flat for blacks. The authors hypothesized that this may be attributable to a slower improvement in CHD risk factors in blacks over this same period. Later studies, also with NHANES data, have shown that being African-American but not Hispanic/Mexican was associated with having undiagnosed angina [43].

Povsic evaluated patients with angina presenting to a single center over a 13-year period [44]. This study utilized 1908 patients with class II–VI angina who had undergone cardiac catheterization and who had been clinically stable for 60 days post-procedure. African-American race had a hazard ratio of 1.32 for the composite endpoint of the 3-year incidence of death, MI, stroke, cardiac re-hospitalization, or revascularization. This study over-represented white patients (almost 80 %) and under-represented African-Americans. Only 5 % in the study were “Native American/Other” demonstrating further under-representation of large minority groups such as Hispanic and Asian-Americans.

Studies of angina in US Hispanics are limited to date. It has been estimated that the prevalence is currently 3.5 %, having increased in Mexican men and women from 1971 to 1994 [1, 9••, 45]. With newer large cohorts that include, and exclusively focus on, Hispanic subjects, there will be further investigation into this relatively un-explored aspect of CHD.

Acute Coronary Syndrome

There have been numerous studies investigating presentation, diagnosis, and management of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) and the influence of race [1, 9••, 46–48]. Despite the attention, recent studies continue to demonstrate disparities in management and outcomes. Although death rates from CHD have been declining nationally, the age-adjusted death rate from CHD is higher among non-Hispanic blacks than any other racial/ethnic group. The rate of premature CHD death is higher among non-Hispanic blacks than their white counterparts [49]. In a recent study, it was found that African-Americans with confirmed ACS were younger, poorer, and less educated and had a longer pre-hospital delay than whites [50].

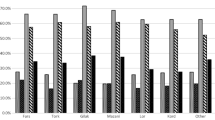

Rates of ACS in the African-American community have been much higher than those in other races, with the incidence in black women outpacing that in white men (Fig. 2) [1]. While mortality and many CHD risk factors appear at higher rates in African-Americans, studies have shown that race can be associated with some positive aspects such as lower risk of cardiogenic shock following STEMI [51]. Recently, African-Americans, Asians, and Hispanics were seen to receive aspirin from emergency medical services in the setting of suspected ACS at higher rates than non-Hispanic whites [52].

Average age-adjusted first MI or fatal CHD incidence rates by sex and race [1] (ARIC participants, ages 35–84 years old)

Medication adherence is an important tenant of secondary prevention of ACS. Using 7955 subjects, the TRANSLATE-ACE investigators examined persistence of medication use after MI and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [53]. Focusing on five medication classes with class I indications, use was evaluated 6 months after MI and PCI. The study found that black race was correlated with non-persistence. Some factors associated with increased persistence were white race, private insurance, patient assistance programs, and having follow-up scheduled prior to discharge.

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

In 2010, it was estimated that over 950,000 PCI procedures were performed [1]. PCI is often performed emergently in the treatment of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) where racial disparity has previously been shown in the time to treatment and the overall treatment rates [54•]. However, it has been seen that door-to-balloon times have improved over time and narrowed (but not eliminated) disparity [55]. Most recently, in looking at a registry of 14,518 patients transferred from a non-PCI to a PCI center for primary PCI treatment, it was found that those with first door-to-device times greater than 120 min were 19 % more likely to be of non-white race [56].

For decades, it has been recognized that there is a disparity in the rate that PCI revascularization procedures are performed for African-Americans when compared to white patients [57, 58]. Retrospective analysis by Gaglia has also revealed that African-American race was associated with lower rates of drug-eluting stent (DES) usage while there was no significant difference between Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites [59•]. While this was meant to highlight a racial disparity, implying that lower DES usage was equivalent to substandard care, there has also been literature demonstrating worse outcomes with DES in African-American patients. Adverse events in this study were due to stent thrombosis despite higher levels of adherence to dual anti-platelet therapy [60]. Later studies also looked at revascularization in Hispanic subjects and found similar results to Gaglia—lower rates of PCI in minority groups despite similar insurance coverage [61]. However, with the emphasis placed on disparities, there have been more efforts put towards correcting them. At centers where the minority population was not receiving appropriately timed primary PCI, quality improvement projects have been shown to correct some disparity [62].

A review of a nationwide database of over 8 million PCI procedures described the trends in DES usage since their introduction [63]. Contained within the overall trends were breakdowns in stent type based on cohorts highlighting potential disparities in care in women and African-Americans. Similar low rates of DES use were found in the elderly and those with Medicare, Medicaid, and no insurance when compared to those with private insurance.

Using 46,245 STEMI patients from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcome Network-Get With The Guidelines Registry (ACTION Registry-GWTG), Guzman compared treatment of Hispanic patients to that of non-Hispanic Caucasians [64]. Hispanics had longer time of symptom onset to hospital arrival, arrival to ECG, and door-to-balloon time. They had lower percentages of ambulance use, pre-hospital ECG, arrival to ECG in less than 10 min, and door-to-balloon time of less than 90 min. While there were no significant differences in the first 24 h in-hospital treatments (diagnostic catheterization, reperfusion therapy, primary PCI, DES use), fewer Hispanics received exercise counseling and referrals to cardiac rehabilitation. Despite the disparities in pre-hospital metrics, no significant differences were found in evidence-based discharge medications or unadjusted in-hospital death. With many similar metrics examined, Hispanics had previously been found to have been treated more conservatively (with fewer invasive revascularization procedures) when hospitalized for non-STEMI ACS [46].

Earlier this year, Olafiranye compared long-term outcomes in both bare metal and DES placement [65•]. This study used the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Registry of 3326 patients to compare whites and African-Americans. Contrary to the nationwide database used by Gaglia, this group had no significant difference in DES usage between the racial groups. African-Americans treated with DES had a higher rate of stent thrombosis compared to whites, but this did not reach statistical significance. The authors found that in both white and black patients, DES was more effective in reducing death or recurrent MI over 2 years. While there was a decreased need for repeat revascularization with DES use in both groups, the effect was attenuated in blacks after statistical adjustment which the authors attributed to the lower sample size.

Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting

In 2010, approximately 397,000 bypass surgeries were performed in the USA [1]. It has been recognized that the mortality rates and readmission rates post-coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) are worse in black patients than other races [66–68]. Hospital quality has been found to have a significant effect as minority patients are more likely to be treated at centers with worse surgical mortality. In the Rangrass study, hospital differences were responsible for 34 % of the difference between African-Americans and whites and 54 % of the outcomes between Hispanics and whites [67••]. An additional 30 % of the disparity was attributed to socioeconomic factors. Even after controlling for differences in hospital quality, disparity remains which has not been fully evaluated to date.

A recent review examined disparities after cardiac surgery focusing on the previously described issues of hospital quality in addition to other contributing factors [69]. The authors found that although there were proposed differences in biological factors and burden of comorbid conditions, the most important determinants of disparity were socioeconomic and hospital factors. It was found that African-Americans often have lower access to more highly ranked hospitals and disproportionately sought care at poor-quality hospitals. A number of explanations were proposed for the differences in hospital quality such as referral patterns that remain left over from the era of institutionalized segregation, residential segregation, and increased use of safety net hospitals.

The review goes on to examine ways which the deficits in CABG quality of care may be addressed and improved. Reaching somewhat broadly, the authors emphasize that the primary reason behind the disparity is the difference in socioeconomic factors. From a more medical standpoint, emphasis can be placed on removing the barriers to care at higher quality hospitals. The authors highlight a study where more than 40 % of African-American Medicare patients hospitalized in 2004 were admitted to just 5 % of the hospitals in the country. Quality improvement efforts at those hospitals which lag the farthest behind standard of care could yield large gains with relatively concentrated efforts.

Pollock reviewed outcomes at a single center looking for the effects of gender and racial outcomes on isolated CABG performed for 8154 consecutive patients at Baylor University Medical Center [70]. While this study echoed those which previously had shown an increased mortality in female patients compared to males, there was no significant difference in operative mortality between white, African-American, and Hispanic patients. The parity between races in this study could be explained by all subjects being treated at the same high-volume, high-quality center. This study was hindered by a somewhat smaller sample size compared to previous studies. Additionally, only 7.3 % of patients in this study were classified as Hispanic, far below the average in Texas.

Platelet Aggregation

Genetic differences along racial lines have been used to investigate questions of whether differences in platelet function can be responsible for disparity in CHD and stroke. Studies of platelet function have found differences in response to pro- and anti-aggregation signaling between races [71, 72]. With the identification of different pathways between races, it is important to consider generalizability while developing new anti-platelet drugs [73]. As technology improves, it becomes easier to perform larger studies in genomics using genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [74]. A recent GWAS by Qayyum identified novel loci which were associated with agonist-mediation platelet aggregation in African-Americans but not European Americans [75]. Similar studies will need to be continued to assess the heritable aspects of platelet aggregation and to examine their effect on large-scale treatment of CHD across race and ethnic groups.

Using the cohort from the PLATO trial, there was no difference in bleeding events found in Asian subjects treated with ticagrelor compared to clopidogrel when compared to the rest of the study cohort [76]. The authors did note the relatively small Asian cohort relative to the entire study population. Citing the small percentage of black subjects included in the PLATO trial, a pilot cross-over study with 34 subjects was performed to examine the onset and degree of platelet inhibition in black subjects with stable coronary disease taking ticagrelor compared to those already taking clopidogrel [77]. It was found that ticagrelor provided greater platelet inhibition than clopidogrel and demonstrated pharmacokinetics similar to previously reported studies. The authors emphasized the importance of investigating new CHD treatments and strengthening an evidence base in the black population. To this end, reducing disparities (under-representation of minorities) in clinical trials of CHD treatments and therapies is an ongoing challenge.

Future Directions

Much of the disparity which still exists with CHD in ethnic minorities can be attributed to the persistent gaps in socioeconomic status and health care system-level factors. Compounding the disparity is the fact that ethnic and racial minorities had made up 55 % of the uninsured population prior to the passage of the Affordable Care Act [78]. These gaps contribute to an increased level of cardiovascular risk factors as well as decreased access to both primary care and inadequate treatment options when disease develops. While socioeconomic equality may be outside of the range of the medical system, health care reforms have already increased the number of patients with access to care. Since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, the Department of Health and Human Services estimates that the uninsured rate for African-Americans has dropped by 9.2 % (2.3 million) and by 12.3 % (4.2 million) in Hispanics [79].

On a smaller scale, there are coverage providers starting to focus more on primary prevention in the area of CHD. Using the University of Michigan employees as a study population, Burke estimated the effectiveness of a hypothetical intervention which focused on primary prevention [80]. They questioned whether targeting interventions in risk factor improvement would have improved cost savings by targeting minority employees or any employee at high risk for CHD. It was found that even though these hypothetical interventions would result in better cost savings across high-risk employees, 75 % of CHD events in African-American employees could also be prevented due to the high prevalence of CHD risk factors in the minority population.

Conclusions

Many of the largest CHD studies to date have been limited to white or African-American cohorts. As the USA becomes increasingly diverse with the rise of populations of Asian and Latin American descent, more attention should be paid to designing cohorts that reflect the general population.

CHD disparities exist for ethnic minorities in the USA. These range from differences in CHD treatments and outcomes to a lack of epidemiological studies involving minorities. Efforts need to be made to expand the knowledge base regarding CHD in the US Hispanic and Asian-American population. With the African-American population, there have been numerous studies documenting disparities in CHD risk factors, treatment, and outcomes. Many of these disparities remain related to patient-level factors (medication adherence, health literacy), health care system factors (access to care, differential treatment, and referral patterns), and environmental factors (socioeconomic status). While it is important to define each of these issues, more focus will need to fall on effective means for primordial and secondary prevention along with risk factor recognition and management.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–322.

Chan PS. The gap in current disparities research a lesson from the community. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:785–6.

Bureau UC. Millennials outnumber baby boomers and are far more diverse [internet]. Available from: http://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2015/cb15-113.html?intcmp=sldr2.

Sardar M, Badri M, Prince CT, Seltzer J, Kowey PR. Underrepresentation of women, elderly patients, and racial minorities in the randomized trials used for cardiovascular guidelines. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1868–70. An examination of RCTs which contributed to published guidelines which shows underrepresentation of women, minorities, and the elderly which may limit the generalizability of certain guidelines.

Census.gov [Internet]. [cited 2015 Jul 16]. Available from: http://www.census.gov/.

Bureau UC. New census bureau report analyzes U.S. population projections [internet]. [cited 2015 Sep 12]. Available from: http://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2015/cb15-tps16.html.

CDC - Hispanic - Latino - populations - racial - ethnic - minorities - minority health [internet]. [cited 2015 Jul 16]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/populations/REMP/hispanic.html#10.

Liao Y, Cooper RS, Cao G, Kaufman JS, Long AE, McGee DL. Mortality from coronary heart disease and cardiovascular disease among adult U.S. Hispanics: findings from the National Health Interview Survey (1986 to 1994). J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:1200–5.

Rodriguez CJ, Allison M, Daviglus ML, Isasi CR, Keller C, Leira EC, et al. Status of cardiovascular disease and stroke in Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: a science advisory from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2014;130:593–625. This is a comprehensive examination of cardiovascular disease in Hispanics in the USA. It not only describes traditional epidemiology concepts and risk factors but also touches on aspects of health and culture that are unique to Hispanics/Latinos.

Sorlie PD, Avilés-Santa LM, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Kaplan RC, Daviglus ML, Giachello AL, et al. Design and implementation of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:629–41.

Sempos CT, Bild DE, Manolio TA. Overview of the Jackson Heart Study: a study of cardiovascular diseases in African American men and women. Am J Med Sci. 1999;317:142–6.

Investigators TA. The atherosclerosis risk in communit (aric) stui)y: design and objectwes. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:687–702.

Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, Hughes GH, Hulley SB, Jacobs DR, et al. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:1105–16.

Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Roux AVD, Folsom AR, et al. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–81.

Daviglus ML, Talavera GA, Avilés-Santa M, et al. Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. JAMA. 2012;308:1775–84. This paper not only describes the epidemiology of risk factors in Hispanics/Latinos but also highlights the considerable heterogeneity in this population.

Kurian AK, Cardarelli KM. Racial and ethnic differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors: a systematic review. Ethn Dis. 2007;17:143–52.

Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the United States. Circulation. 2005;111:1233–41.

Jose PO, Frank ATH, Kapphahn KI, Goldstein BA, Eggleston K, Hastings KG, et al. Cardiovascular disease mortality in Asian Americans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2486–94. This study used a very large sample (10,442,034) to examine mortality rates in Asian Americans. The authors also detailed the significant differences between the extremely different groups which are lumped into the “Asian” classification.

Sorlie PD, Backlund E, Johnson NJ, Rogot E. Mortality by Hispanic status in the United States. JAMA. 1993;270:2464–8.

Cortes-Bergoderi M, Goel K, Murad MH, Allison T, Somers VK, Erwin PJ, et al. Cardiovascular mortality in Hispanics compared to non-Hispanic whites: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the Hispanic paradox. Eur J Intern Med. 2013;24:791–9.

Abraído-Lanza AF, Dohrenwend BP, Ng-Mak DS, Turner JB. The Latino mortality paradox: a test of the “salmon bias” and healthy migrant hypotheses. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1543–8.

Ruiz JM, Steffen P, Smith TB. Hispanic mortality paradox: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the longitudinal literature. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e52–60.

Medina-Inojosa J, Jean N, Cortes-Bergoderi M, Lopez-Jimenez F. The Hispanic paradox in cardiovascular disease and total mortality. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;57:286–92.

Caleyachetty R, Echouffo-Tcheugui JB, Muennig P, Zhu W, Muntner P, Shimbo D. Association between cumulative social risk and ideal cardiovascular health in US adults: NHANES 1999–2006. Int J Cardiol. 2015;191:296–300.

Folsom AR, Yatsuya H, Nettleton JA, Lutsey PL, Cushman M, Rosamond WD, et al. Community prevalence of ideal cardiovascular health, by the American Heart Association definition, and relationship with cardiovascular disease incidence. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1690–6.

Dong C, Rundek T, Wright CB, Anwar Z, Elkind MSV, Sacco RL. Ideal cardiovascular health predicts lower risks of myocardial infarction, stroke, and vascular death across whites, blacks, and hispanics: the northern Manhattan study. Circulation. 2012;125:2975–84.

Rodriguez CJ. Disparities in ideal cardiovascular health: a challenge or an opportunity? Circulation. 2012;125:2963–4.

Kwagyan J, Retta TM, Ketete M, Bettencourt CN, Maqbool AR, Xu S, et al. Obesity and cardiovascular diseases in a high-risk population: evidence-based approach to CHD risk reduction. Ethn Dis. 2015;25:208–13.

Goff DC, Bertoni AG, Kramer H, Bonds D, Blumenthal RS, Tsai MY, et al. Dyslipidemia prevalence, treatment, and control in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) gender, ethnicity, and coronary artery calcium. Circulation. 2006;113:647–56.

Bennet A, Di Angelantonio E, Erqou S, Eiriksdottir G, Sigurdsson G, Woodward M, et al. Lipoprotein(a) levels and risk of future coronary heart disease: large-scale prospective data. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:598–608.

Virani SS, Brautbar A, Davis BC, Nambi V, Hoogeveen RC, Sharrett AR, et al. Associations between lipoprotein(a) levels and cardiovascular outcomes in black and white subjects: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Circulation. 2012;125:241–9.

Guan W, Cao J, Steffen BT, Post WS, Stein JH, Tattersall MC, et al. Race is a key variable in assigning lipoprotein(a) cutoff values for coronary heart disease risk assessment: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:996–1001.

Daviglus ML, Pirzada A, Talavera GA. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in the Hispanic/Latino population: lessons from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2014;57:230–6.

Rodriguez CJ, Cai J, Swett K, González HM, Talavera GA, Wruck LM, et al. High cholesterol awareness, treatment, and control among Hispanic/Latinos: results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001867.

Kershaw KN, Osypuk TL, Do DP, Chavez PJD, Roux AVD. Neighborhood-level racial/ethnic residential segregation and incident cardiovascular disease the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2015;131:141–8. This study goes beyond the usual examination of non-traditional risk factors and uses neighborhood segregation as an independent variable for cardiovascular disease.

NHANES - National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Homepage [Internet]. [cited 2015 Aug 13]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm.

de Souza RJ, Anand SS. Cardiovascular disease in Asian Americans: unmasking heterogeneity∗. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:2495–7.

Yeboah J, McClelland RL, Polonsky TS, et al. Comparison of novel risk markers for improvement in cardiovascular risk assessment in intermediate-risk individuals. JAMA. 2012;308:788–95.

Bild DE. Ethnic differences in coronary calcification: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation. 2005;111:1313–20.

McClelland RL, Chung H, Detrano R, Post W, Kronmal RA. Distribution of coronary artery calcium by race, gender, and age: results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circulation. 2006;113:30–7.

Alluri K, McEvoy JW, Dardari ZA, Jones SR, Nasir K, Blankstein R, et al. Distribution and burden of newly detected coronary artery calcium: results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2015;9:337–44.e1. This study uses a relatively new risk factor and describes disease patterns by race.

Will JC, Yuan K, Ford E. National trends in the prevalence and medical history of angina: 1988 to 2012. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:407–13.

McKee MM, Winters PC, Fiscella K. Low education as a risk factor for undiagnosed angina. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25:416–21.

Povsic TJ, Broderick S, Anstrom KJ, Shaw LK, Ohman EM, Eisenstein EL, et al. Predictors of long‐term clinical endpoints in patients with refractory angina. J Am Heart Assoc Cardiovasc Cerebrovasc Dis [Internet]. 2015, 4. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4345862/.

Ford ES, Giles WH. Changes in prevalence of nonfatal coronary heart disease in the United States from 1971–1994. Ethn Dis. 2003;13:85–93.

Cohen MG, Roe MT, Mulgund J, Peterson ED, Sonel AF, Menon V, et al. Clinical characteristics, process of care, and outcomes of Hispanic patients presenting with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: results from Can Rapid risk stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress ADverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA Guidelines (CRUSADE). Am Heart J. 2006;152:110–7.

Hayes DK, Greenlund KJ, Denny CH, Neyer JR, Croft JB, Keenan NL. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in health-related quality of life among people with coronary heart disease, 2007. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A78.

Deshmukh M, Joseph MA, Verdecias N, Malka ES, LaRosa JH. Acute coronary syndrome: factors affecting time to arrival in a diverse urban setting. J Community Health. 2011;36:895–902.

Gillespie CD, Wigington C, Hong Y, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Coronary heart disease and stroke deaths—United States, 2009. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ. 2013;62 Suppl 3:157–60.

DeVon HA, Burke LA, Nelson H, Zerwic JJ, Riley B. Disparities in patients presenting to the emergency department with potential acute coronary syndrome: it matters if you are Black or White. Heart Lung J Acute Crit Care. 2014;43:270–7.

Movahed MR, Khan MF, Hashemzadeh M, Hashemzadeh M. Age adjusted nationwide trends in the incidence of all cause and ST elevation myocardial infarction associated cardiogenic shock based on gender and race in the United States. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2015;16:2–5.

Tataris KL, Mercer MP, Govindarajan P. Prehospital aspirin administration for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) in the USA: an EMS quality assessment using the NEMSIS 2011 database. Emerg Med J EMJ 2015.

Mathews R, Wang TY, Honeycutt E, Henry TD, Zettler M, Chang M, et al. Persistence with secondary prevention medications after acute myocardial infarction: insights from the TRANSLATE-ACS study. Am Heart J. 2015;170:62–9.

Cavender MA, Rassi AN, Fonarow GC, Cannon CP, Peacock WF, Laskey WK, et al. Relationship of race/ethnicity with door-to-balloon time and mortality in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: findings from get with the guidelines—coronary artery disease. Clin Cardiol. 2013;36:749–56. This study highlights persistent disparities in an important benchmark of CHD treatment quality. Despite the residual disparity, improvement in quality metrics was observed in all groups studied.

Curtis JP, Herrin J, Bratzler DW, Bradley EH, Krumholz HM. Trends in race-based differences in door-to-balloon times. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:992–3.

Dauerman HL, Bates ER, Kontos MC, Li S, Garvey JL, Henry TD, et al. Nationwide analysis of patients with ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction transferred for primary percutaneous intervention findings from the American Heart Association Mission: Lifeline Program. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:e002450.

Ayanian JZ, Udvarhelyi IS, Gatsonis CA, Pashos CL, Epstein AM. Racial differences in the use of revascularization procedures after coronary angiography. JAMA. 1993;269:2642–6.

Whittle J, Conigliaro J, Good CB, Lofgren RP. Racial differences in the use of invasive cardiovascular procedures in the Department of Veterans Affairs Medical System. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:621–7.

Gaglia MA, Shavelle DM, Tun H, Bhatt J, Mehra A, Matthews RV, et al. African-American patients are less likely to receive drug-eluting stents during percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc Revasc Med Mol Interv. 2014;15:214–8. This is a recent study that highlights that there is still an impact of race on the decision to use DES which can extend beyond other markers of socioeconomic status.

Batchelor WB, Ellis SG, Ormiston JA, Stone GW, Joshi AA, Wang H, et al. Racial differences in long-term outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention with paclitaxel-eluting coronary stents. J Intervent Cardiol. 2013;26:49–57.

Cram P, Bayman L, Popescu I, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS. Racial disparities in revascularization rates among patients with similar insurance coverage. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:1132–9.

Bhalla R, Yongue BG, Currie BP, Greenberg MA, Myrie-Weir J, DeFino M, et al. Improving primary percutaneous coronary intervention performance in an urban minority population using a quality improvement approach. Am J Med Qual. 2010;25:370–7.

Bangalore S, Gupta N, Guo Y, Feit F. Trend in the use of drug eluting stents in the United States: insight from over 8.1 million coronary interventions. Int J Cardiol. 2014;175:108–19.

Guzman LA, Li S, Wang TY, Daviglus ML, Exaire J, Rodriguez CJ, et al. Differences in treatment patterns and outcomes between Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites treated for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: results from the NCDR ACTION Registry—GWTG. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:630–1.

Olafiranye O, Vlachos H, Mulukutla SR, Marroquin OC, Selzer F, Kelsey SF, et al. Comparison of long-term safety and efficacy outcomes after drug-eluting and bare-metal stent use across racial groups: insights from NHLBI Dynamic Registry. Int J Cardiol. 2015;184:79–85. This study describes a significant difference in outcome by race after the usage of DES. Further work will be needed to determine the precise cause of this difference.

Becker ER, Rahimi A. Disparities in race/ethnicity and gender in in-hospital mortality rates for coronary artery bypass surgery patients. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98:1729–39.

Rangrass G, Ghaferi AA, Dimick JB. Explaining racial disparities in outcomes after cardiac surgery: the role of hospital quality. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:223–7. A large number of subjects (173,925) were used to provide convincing evidence that hospital quality is a major source of the disparities in outcomes between races. There is still a large fraction of the disparity in outcomes that remains unexplained.

Girotti ME, Shih T, Revels S, Dimick JB. Racial disparities in readmissions and site of care for major surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:423–30.

Khera R, Vaughan-Sarrazin M, Rosenthal GE, Girotra S. Racial disparities in outcomes after cardiac surgery: the role of hospital quality. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17:29.

Pollock B, Hamman BL, Sass DM, da Graca B, Grayburn PA, Filardo G. Effect of gender and race on operative mortality after isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:614–8.

Tourdot BE, Conaway S, Niisuke K, Edelstein LC, Bray PF, Holinstat M. Mechanism of race-dependent platelet activation through the protease-activated receptor-4 and Gq signaling axis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:2644–50.

Bray PF, Mathias RA, Faraday N, Yanek LR, Fallin MD, Herrera-Galeano JE, et al. Heritability of platelet function in families with premature coronary artery disease. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:1617–23.

Edelstein LC, Simon LM, Montoya RT, Holinstat M, Chen ES, Bergeron A, et al. Racial difference in human platelet PAR4 reactivity reflects expression of PCTP and miR-376c. Nat Med [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2015 Sep 21];19. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3855898/.

Carty CL, Keene KL, Cheng Y-C, Meschia JF, Chen W-M, Nalls M, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies identifies genetic risk factors for stroke in African Americans. Stroke. 2015;46:2063–8.

Qayyum R, Becker LC, Becker DM, Faraday N, Yanek LR, Leal SM, et al. Genome-wide association study of platelet aggregation in African Americans. BMC Genet [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2015 Sep 21];16. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4448541/.

Kang H-J, Clare RM, Gao R, Held C, Himmelmann A, James SK, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in Asian patients with acute coronary syndrome: a retrospective analysis from the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) Trial. Am Heart J. 2015;169:899–905.e1.

Waksman R, Maya J, Angiolillo DJ, Carlson GF, Teng R, Caplan RJ, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in black patients with stable coronary artery disease prospective, randomized, open-label, multiple-dose, crossover pilot study. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2015;8:e002232.

13 M, 2013. Health coverage by race and ethnicity: the potential impact of the affordable care act [internet]. [cited 2015 Sep 13]. Available from: http://kff.org/disparities-policy/issue-brief/health-coverage-by-race-and-ethnicity-the-potential-impact-of-the-affordable-care-act/.

Health Insurance Coverage and the Affordable Care Act [Internet]. ASPE. [cited 2015 Sep 13]. Available from: http://aspe.hhs.gov/pdf-document/health-insurance-coverage-and-affordable-care-act.

Burke JF, Vijan S, Chekan LA, Makowiec TM, Thomas L, Morgenstern LB. Targeting high-risk employees may reduce cardiovascular racial disparities. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20:725–33.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

J. Adam Leigh and Manrique Alvarez declare that they have no conflict of interest. Carlos J. Rodriguez declares personal fees from Alnylam and non-financial support from AMGEN and Merck.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Coronary Heart Disease

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Leigh, J.A., Alvarez, M. & Rodriguez, C.J. Ethnic Minorities and Coronary Heart Disease: an Update and Future Directions. Curr Atheroscler Rep 18, 9 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-016-0559-4

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-016-0559-4