Abstract

Purpose of Review

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) affects 20% of children. However, diagnosis of ACD may be underreported in children due to lack of recognition. Patch testing is the gold standard for evaluation of ACD in children but poses unique challenges in this population.

Recent Findings

Recent studies highlight the significance of ACD and the utility of patch testing in children. Evaluation of ACD in children is difficult and requires knowledge of a child’s exposure history, careful selection of allergens, and knowledge of specialized patch testing considerations to minimize irritation and maximize cooperation. Until recently, there were no agreed upon patch test series for children. In 2018, a comprehensive pediatric baseline series was published enabling thorough evaluation of ACD in children (Yu J, Atwater AR, Brod B, Chen JK, Chisolm SS, Cohen DE, et al. Dermatitis. 2018;29(4):206–12).

Summary

This review provides an overview of the current literature, an update on pediatric ACD, and patch testing methods in children to effectively evaluate and manage ACD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) occurs in children at a similar frequency compared with adults [1]. ACD is a frequent comorbidity in children with underlying atopic dermatitis (AD) [2•]. Sensitization to contact allergens may develop as early as infancy [3]. According to recent publications, 27 to 95.6% of children with suspected ACD have sensitization to one or more allergens [4•]. In addition, children with and without AD can develop ACD. Recognizing discerning clinical features can prevent the delay of diagnosis in children with concurrent ACD and AD [2•, 5•]. Patch testing is the gold standard for diagnosing ACD in children. The Thin-Layered Rapid Use Epicutaneous (TRUE) test (Smart Practice, AZ, USA) is the only Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved patch test series for use in children 6 to 17 years [6]. However, due to the limitations of the TRUE test including the inability to add or subtract allergens, more expert-driven comprehensive patch testing series have recently been published for use in children in the USA and abroad. We present an update of the recent literature on pediatric ACD and discuss important indications, techniques, and our clinical experience of patch testing in children to effectively evaluate and manage ACD in pediatric patients.

Pathophysiology of Allergic Contact Dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis is a T cell mediated, delayed type IV hypersensitivity reaction caused by cutaneous exposure to a sensitizing allergen. During the sensitization phase, the allergen comes into contact with the skin leading to the engulfment and processing by antigen presenting cells [7]. Subsequently, these antigen presenting cells migrate to regional lymph nodes where it is presented to naïve T cells leading to clonal expansion of memory T cells [7]. In the elicitation phase, re-exposure of the allergen leads to activation and mobilization of memory T cells to the site of allergen exposure eliciting the clinical manifestation of ACD which includes pruritus, erythema, weeping, crusting, scaling, hyperkeratosis, and lichenification [7]. ACD is primarily driven by T helper 1 cells and cytotoxic T cells; however, recent research has also implicated that Th2, Th17, and Th22 cells may be involved in the development of ACD as there is some evidence suggesting the use of dupilumab, a IL-4/13 inhibitor, for ACD [8,9,10].

Allergic Contact Dermatitis in Children

Compared with adults, there are few large-scale studies of pediatric ACD that have been published in North America and Europe. The two largest North American studies are the North American Contact Dermatitis Group (NACDG) [1] and the Pediatric Contact Dermatitis Registry (PCDR) [5•]. The largest pediatric contact dermatitis study from Europe is the European Surveillance System on Contact Allergies (ESSCA) from 2005 to 2010 [11]. The NACDG examined 883 children younger than 18 years referred for patch testing from 2005 to 2012 [1]. This study found that children and adults had similar rates of contact sensitization with 56.7% of children having a relevant positive patch test reaction (RPPT) [1]. Children and adults demonstrated significantly different RPPT for 27 allergens. Children were more likely to have a relevant reaction to nickel, cobalt, and Compositae mix but less likely to react to fragrance mix I, balsam of Peru (Myroxylon pereirae), and formaldehyde than adults. This suggests that children may have unique environmental exposures and allergen sensitivities than adults. Furthermore, investigators found that the TRUE test would have only detected all of the positive patch test (PPT) reactions in 67% of children who underwent patch testing [1].

The PCDR is a multicenter, retrospective study of 1142 children patch tested between 2015 and 2016 [5•]. Forty-eight percent of children had one or more RPPT, and 48.3% of patients had concurrent ACD and AD [5•]. The top ten allergens among children consisted of metals (nickel, cobalt, and gold), fragrances (fragrance mix I and balsam of Peru, topical antibiotics (neomycin and bacitracin), emollient/emulsifier (propylene glycol), and surfactants (cocamidopropyl betaine (CAPB)). This study compared sensitization rates between younger (0–5 years) and older children (6–18 years) and found that younger children were more likely to have relevant sensitizations to Compositae mix, CAPB, and dimethyl dimethylol hydantoin than older children possibly from exposure to personal care products including shampoos and body washes. Older children were more likely to have relevant sensitizations to disperse blue dyes and gold through exposure to disperse blue dyes from clothing, food dyes, and toys [12].

The ESSCA study examined 6708 children (1 to 16 years) patch tested between 2005 and 2010 across 11 European countries [11]. The prevalence of one or more PPT in the cohort was 36.9%. Younger children (0–5 years) had the highest prevalence of one or more PPT (45.3%) compared with children (6–12 years) (33.3%) and older children (13–16 years) (34.4%). Furthermore, there was no difference in the prevalence of one or more PPT between boys and girls as well as between children with AD and without AD. Allergen sensitization rates may vary by geographic regions. The 10 most frequent allergens in children aged 1 to 16 years in European countries were nickel sulfate, cobalt chloride, potassium dichromate, neomycin sulfate, balsam of Peru, para-phenylenediamine, methylchloroisothiazolinone (MCI)/methylisothiazolinone (MI), fragrance mix, lanolin alcohols, and colophony [11].

Allergic Contact Dermatitis and Atopic Dermatitis

One of the primary challenges in the diagnosis of ACD in children is the high prevalence of AD in children which has been estimated to be as high as 20% and maintaining a sensitive threshold to test children with AD [13]. The coexistence of ACD and AD was previously thought to be an inverse relationship due to the differing T helper cell lineages implicated in the pathophysiology [14]. Recent studies have highlighted the high prevalence of ACD in children with AD [1, 2•, 15, 16]. Lubbes et al. found that in 1012 children (0–17 years) patch tested between 1996 and 2013, the prevalence of positive patch test reactions was similar between children with AD (48%) and children without AD (47%) [15]. In another study, AD patients were found to be statistically more likely to have one or more PPT [17].

It is difficult to clinically differentiate between AD and ACD in children as oftentimes both skin conditions involve similar areas on the body including the lip, eyelids, hands, and flexural distributions [18]. Skin barrier abnormalities in patients with AD could increase allergen exposure with repeated application of topical medications and emollients possibly leading to higher risk of contact sensitization [19]. Halling-Overgaard et al. found that patients with AD had a nearly two-fold increase in cutaneous absorption of topical medicaments compared with patients without AD [20]. In addition, the frequent use of topical treatments in AD patients such as emollients and medicaments could lead to the development of sensitization to ingredients used in these topical treatments, thus leading to differing sensitization profiles between AD and non-AD patients [21]. Furthermore, contact sensitization may negatively influence AD skin, amplifying the effects of contact irritants and allergens on the skin. It is important to maintain a high index of suspicion for ACD in AD patients, especially in children with worsening of AD or AD refractor to topical treatments to prevent a delay of ACD diagnosis.

According to the PCDR study, AD patients were more likely to be sensitized to CAPB, lanolin, tixocortol-21-pivalate, and parthenolide, which are commonly found in skin care products used by AD patients [2•]. Notably, it has been shown that patch testing with the patient’s personal products such as topical corticosteroids, antibiotics, and emollients may be instrumental in identifying culprit allergens [22].

Evaluation of Allergic Contact Dermatitis in Children

Indications for Patch Testing in Children

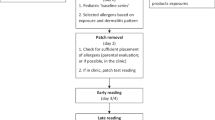

Patch testing is the gold standard for the diagnosis of ACD in children. Patch testing is indicated in children with a suspected history of ACD (acute or chronic), worsening or chronic recalcitrant dermatitis (> 2 months) despite topical treatment including patients with history of AD, dermatitis presented with atypical distributions such as face, eyelids, hands and feet, and groin, adolescent or adult onset AD without history of childhood eczema, and severe or widespread dermatitis before initiating systemic therapy [21, 23,24,25]. Children presented with any of these findings should raise clinical suspicion for ACD, and referral for patch testing is recommended. A suggested algorithm for patch testing in children is provided in Fig. 1.

Pre-Patch Testing Considerations

Patch testing in children is a unique challenge due to compliance and collaboration needed from both the patient and parents to ensure that the testing is carried out properly. Patch testing requires three visits including an initial visit to obtain a history and for patch application, a second visit 24 to 48 h later for patch removal, and a final visit 72 to 96 h after patch placement for evaluation and counseling. The first and third visits can last anywhere from 30 to 60 min. Parents should be informed that the delayed patch test reactions may occur up to 3 weeks after patch testing in some patients [23]. At our center, parents are instructed to be aware of any new reactions that may occur during this period; however, remarking of the patches is not necessary, and patients can resume normal activities. If new reactions occur, patients are asked to take a close-up picture of the site of reaction and the entire back. The patch test expert will work with the parent and patient to figure out if this represents an actual delayed patch test reaction and if so identify the culprit allergen. This may require additional visits and re-testing of certain allergens.

Patches should be marked and reinforced with hypoallergenic adhesive tape to avoid dislodging (Fig. 2). Patients should be advised to wear a dark shirt at the patch application visit to avoid staining clothes from markings. Throughout the week, patients should keep their back dry by avoiding baths and showers, as well as minimizing strenuous physical activities such as gym class and sports to avoid sweating and dislodging of the patches.

Parents should also bring in the child’s personal products including moisturizers, emollients, and prescribed and over-the-counter topical treatments. This should be brought in its original container with the ingredient list. Small quantities of leave-on products may be tested if any product is suspected to be the cause of the child’s ACD. Small portions of other items such as rubber from shoes, pieces of clothing, or items from the child’s hobbies or toys may also be tested. Detailed information on test concentration and vehicles for less common substances should be clarified beforehand. The book of De Groot is an extremely useful source of information in this direction [26•].

Children with generalized dermatitis or extensive dermatitis involving the back are not candidates for patch testing due to risk of false-positive or “angry back” reactions and may need to reschedule their visits. Ideally, the child should not be on any systemic immunosuppressants prior to patch testing as this may lead to false-negative readings. However, there are some studies demonstrating that patients on low doses of immunosuppressant such as oral prednisone and methotrexate, and biologic therapies such as dupilumab and adalimumab may still produce clinically relevant patch test reactions [21, 27,28,29,30,31]. Nevertheless, there is a lack of literature regarding the use of systemic immunosuppressive medication and patch testing in children to establish definitive clinical recommendations [21, 25]. Topical corticosteroids on the site of patch testing should also be discontinued at least 1 week prior to patch testing to avoid suppression of patch test reactions [32]. Children presenting for patch testing also should not have a suntan or have intensive ultraviolet radiation exposure on their back for at least 6 weeks prior to testing [33].

Clinical History and Physical Exam

A thorough evaluation of exposures may help uncover relevant allergens in children. Exposures to various personal care products (e.g., moisturizers, shampoos, soaps, diaper wipes, laundry detergents), topical and systemic medication history, hobbies (e.g., toys, arts and crafts, musical instruments), school activities (e.g., sports, games), and after-school occupations are relevant [34,35,36,37]. Children also spend time with other caretakers (e.g., teachers, grandparents, day care), and thus, potential exposures outside the home may also contribute to ACD [38].

Understanding the clinical distribution of ACD in children may also provide significant information to culprit allergens and help select allergens to test (Table 1). The face, hands, feet, arms, and legs are commonly affected areas for pediatric ACD [1, 49]. Sources of ACD involving the face could include personal care products such as shampoos, face creams, and face washes. Other possible sources of facial ACD include connubial ACD from perfumes or para-phenylenediamine hair dye used by caregivers [38]. Sources of eyelid dermatitis include aerosolized products such scented candles and essential oil diffusers, which have gained recent popularity [50]. Airborne contact dermatitis may also affect other exposed sites such as the neck, extensor forearms, and dorsal hands [50].

Hand dermatitis in children could be related to a new popular childhood activity, “slime,” which is typically made with various household substances [40]. Ingredients for “slime” include common allergens such as methylisothiazolinone, fragrances, surfactants, plant-derived allergens, and formaldehyde releasers [40]. Recently, a novel source of methylisothiazolinone, a common allergen among children, has also been identified in certain “water-based” nail polish marketed for children causing hand dermatitis [41].

Leg dermatitis may be associated with shin guards used in sports containing potential allergens such as neoprene rubbers or glues [34, 43]. ACD affecting diaper areas should raise clinical suspicion for ACD as this region is usually spared in patients with AD. Culprit allergens associated with contact dermatitis in the diaper area include botanical extracts, fragrances, and preservatives in diaper wipes as well as disperse dyes and rubber compounds (benzothiazoles) in diapers [44,45,46].

There are also increasing reports of systemic contact dermatitis in children through ingestion, inhalation, and transcutaneous and intravenous exposure of sensitized allergens [47]. Causes of systemic contact dermatitis include common food ingredients such as balsam of Peru (Myroxylon pereirae), propylene glycol, and nickel [47, 48]. Rare cases of systemic contact dermatitis to carmine, a red dye in foods such as red velvet cupcakes, have also been reported in children [51].

Patch Testing Series in Children

While history and physical exam usually provide clues of potential culprit sensitizers, unsuspected allergens may also be clinically relevant. Therefore, a general baseline series of allergens having the highest proportion of clinical relevance in children is recommended for ACD evaluation (Table 2) [23].

The TRUE™ test is FDA approved for patch testing in children over 6 years old. While this allows for convenient in-office patch testing, one concern when using this pre-made patch test is the inability to interchange allergens based on exposure history. This is a critical consideration in younger and smaller children who have limited surface area on the back upon which to perform patch testing. In addition, the TRUE™ test does not contain some of the common pediatric allergens such as methylisothiazolinone, propylene glycol, CAPB, and fragrance mix II [1, 5•]. In 2018, a US-based expert consensus-derived pediatric baseline patch test series consisting of 38 allergens was established for use in children over 6 years old [52••]. Other countries have also proposed baseline series for patch testing in children. Australia has a pediatric baseline series consisting of 30 allergens [53]. Furthermore, the NACDG 70 allergen series, American Contact Dermatitis Core 80 allergen series, and European baseline series are thought to be appropriate screening series in children over 12 years of age, if space allows [1, 49, 54]. The authors’ experience is that the back of a 6-year-old child can fit 40 to 60 allergens [52••].

Patch Testing Technique

Small quantity of allergens dissolved in petrolatum (approximately 20 mg) or aqueous solution (approximately 15 uL of liquid) are deposited in 8 mm Finn Chambers® and applied to the back (avoiding the spine) and affixed with hypoallergenic adhesive (Scanpor, Actavis Norway AS/Norgesplaster, Vennesla, Norway) tapes [32]. When other test chambers are used, the optimal doses of petrolatum and liquid test substances should be based on a dose per unit area [55]. Placement of patches on the abdomen or thighs can also be done. Similar patch test concentrations are used in children and adults. However, special consideration may be needed when testing infants due to potential risk of irritant reactions [23]. Furthermore, it is recommended to test the patient’s personal products in conjunction to baseline series. Leave-on products can be tested as is, and rinse-off products should be diluted in water by 1/100 to 1/1000 to minimize irritation [26•].

The general consensus for adolescent (>13 years) is to follow standard procedure performed in adults with the removal of patches at 48 h and reading at 72 to 96 h [23, 24]. Some centers have proposed for occlusion times of 24 h especially in younger children (< 8 years old) or children with AD or generalized dermatitis to reduce irritant reactions [49, 56]. To increase cooperation from the child during patch application, distraction tools such as games and videos and collaborating with parents to provide motivational incentives for the child can be incorporated [57, 58].

Two readings are generally recommended: the first reading at the time of patch removal and a second reading at 24 to 48 h after patch removal. A delayed (> 72 h after patch removal) reading may be necessary for certain allergens that may cause delayed reactions such as topical antibiotics, corticosteroids, certain preservatives, and metals [59, 60]. In children specifically, one prospective study of 38 children aged 6 to 17 years identified the following allergens causing delayed patch test reactions: quaternium-15, formaldehyde, diazolidinyl urea, epoxy resin, neomycin, and p-tert-butylphenol formaldehyde resin [61]. Patients and parents should also be advised that any delayed reactions may appear as late as 3 weeks after testing.

Patch test reactions are interpreted using standardized criteria by the International Contact Dermatitis Research Group (ICDRG) [62]. It is sometimes difficult to distinguish between irritant and weak positive reactions, especially in patients with AD [21]. However, even questionable reactions can sometimes be clinically relevant. For example, propylene glycol (PG) may present as an irritant or weak positive reaction [63]. Nonetheless, PG is almost always clinically relevant regardless of strength of reaction [63]. The “crescendo” effect of increasing reaction strength between the first and second patch test reading is more likely to indicate a true positive reaction. Determination of clinical relevance of the positive reactions with regard to the child’s history, exposure, and clinical presentation is also of the utmost importance.

Repeated Open Application Test

When suspected allergens produce doubtful or negative results on patch testing, repeated open application test can be utilized by testing specific products or other suitable formulations [32]. This test involves repeated application of the suspected allergens on the volar arm twice daily for 10 to 14 days (up to 3 weeks) and observing for the development of dermatitis [64]. If clinical dermatitis develops after repeated application of the suspected substance, then a weak positive reaction is highly relevant. In contrast, if dermatitis does not develop, the suspected product causing a doubtful or negative reaction is likely not relevant. This can be a useful method for clarifying the relevance of a patch test reaction or evaluating the safety of a new product.

Counseling and Avoidance

Detection, avoidance, and prevention are the main focus of ACD management in children. Because children have less control over their environment than adults, counseling should also involve educating all individuals involved in the care of the child including parents, grandparents, teachers, and caretakers. The American Contact Dermatitis Society Contact Allergy Management Program is a good resource that can be offered to patients to provide a safe product list free of offending allergens and cross-reactors [65].

Pre-Emptive Allergen Avoidance Strategy

Pre-emptively avoiding top offending allergens in children has been suggested especially for children with limited access to patch testing or when patch testing becomes a challenge in those with generalized dermatitis, which could potentially benefit one-third of children suffering ACD [4•]. Pediatricians and pediatric dermatologists can recommend children with eczema and sensitive skin personal care products free of the most common allergens identified among children which includes neomycin, balsam of Peru, fragrances, benzalkonium chloride, lanolin, CAPB, formaldehyde, MCI/MI, propylene glycol, and corticosteroids [4•].

Conclusion

ACD is a common dermatologic problem in children and a high index of suspicion is necessary. A suspected history of ACD, worsening or chronic recalcitrant dermatitis despite topical treatment, prior to starting a systemic immunosuppressive agent, and dermatitis presented with atypical distributions are indications for patch testing in children. Patch testing techniques and methodology in children have been examined and discussed in this review. Clinicians should recognize that many children may have concomitant AD and should maintain a sensitive threshold for ACD evaluation to avoid delay in diagnosis. The availability of the TRUE test and establishment of pediatric baseline series should minimize barriers of patch testing for children [5•]. Furthermore, a thorough evaluation of exposure history and physical exam will provide clues of culprit sensitizers and help guide the selection of allergens to patch test. It is essential to include all caregivers during counseling on avoidance of relevant allergens to improve compliance.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Zug KA, Pham AK, Belsito DV, Dekoven JG, DeLeo VA, Fowler JF, et al. Patch testing in children from 2005 to 2012: results from the North American contact dermatitis group. Dermatitis. 2014;25(6):345–55.

• Jacob SE, McGowan M, Silverberg NB, Pelletier JL, Fonacier L, Mousdicas N, et al. Pediatric contact dermatitis registry data on contact allergy in children with atopic dermatitis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(8):765–70 Large scale study providing patch test data and insight in children with atopic dermatitis and concomitant allergic contact dermatitis.

Fisher AA. Allergic contact dermatitis in early infancy. Cutis. 1994;54(5):300–2.

• Hill H, Goldenberg A, Golkar L, Beck K, Williams J, Jacob SE. Pre-emptive avoidance strategy (P.E.A.S.)-addressing allergic contact dermatitis in pediatric populations. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12(5):551–61 Study highlights common allergens in personal care products for children and preventive strategies for allergic contact dermatitis in children.

• Goldenberg A, Mousdicas N, Silverberg N, Powell D, Pelletier JL, Silverberg JI, et al. Pediatric contact dermatitis registry inaugural case data. Dermatitis. 2016;27(5):293–302 Multcenter study highlighting patch testing data in pediatric patients.

Package Insert - TRUE TEST - ucm294327.pdf. 2018; Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/83084/download. Accessed 4/1/2020

Vocanson M, Hennino A, Rozières A, Poyet G, Nicolas JF. Effector and regulatory mechanisms in allergic contact dermatitis. Allergy. 2009;64(12):1699–714.

Dhingra N, Shemer A, Correa Da Rosa J, Rozenblit M, Fuentes-Duculan J, Gittler JK, et al. Molecular profiling of contact dermatitis skin identifies allergen-dependent differences in immune response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(2):362–72.

Peiser M. Role of Th17 cells in skin inflammation of allergic contact dermatitis. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013:261037.

Jacob SE, Sung CT, Machler BC. Dupilumab for systemic allergy syndrome with dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2019;30(2):164–7.

Belloni Fortina A, Cooper SM, Spiewak R, Fontana E, Schnuch A, Uter W. Patch test results in children and adolescents across Europe. Analysis of the ESSCA Network 2002-2010. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015;26(5):446–55.

Giusti F, Massone F, Bertoni L, Pellacani G, Seidenari S. Contact sensitization to disperse dyes in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20(5):393–7.

Weston WL, Weston JA, Kinoshita J, Kloepfer S, Carreon L, Toth S, et al. Prevalence of positive epicutaneous tests among infants, children, and adolescents. Pediatrics. 1986;78(6):1070–4.

Uehara M, Sawai T. A longitudinal study of contact sensitivity in patients with atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125(3):366–8.

Lubbes S, Rustemeyer T, Sillevis Smitt JH, Schuttelaar ML, Middelkamp-Hup MA. Contact sensitization in Dutch children and adolescents with and without atopic dermatitis – a retrospective analysis. Contact Dermatitis. 2017;76(3):151–9.

Hamann CR, Hamann D, Egeberg A, Johansen JD, Silverberg J, Thyssen JP. Association between atopic dermatitis and contact sensitization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(1):70–8.

Malajian D, Belsito DV. Cutaneous delayed-type hypersensitivity in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(2):232–7.

Aquino M, Fonacier L. The role of contact dermatitis in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2(4):382–7.

Thyssen JP, McFadden JP, Kimber I. The multiple factors affecting the association between atopic dermatitis and contact sensitization. Allergy. 2014;69(1):28–36.

Halling-Overgaard AS, Kezic S, Jakasa I, Engebretsen KA, Maibach H, Thyssen JP. Skin absorption through atopic dermatitis skin: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177(1):84–106.

Chen JK, Jacob SE, Nedorost ST, Hanifin JM, Simpson EL, Boguniewicz M, et al. A pragmatic approach to patch testing atopic dermatitis patients: clinical recommendations based on expert consensus opinion. Dermatitis. 2016;27(4):186–92.

Rodrigues DF, Goulart EM. Patch-test results in children and adolescents: systematic review of a 15-year period. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(1):64–72.

de Waard-van der Spek FB, Darsow U, Mortz CG, Orton D, Worm M, Muraro A, et al. EAACI position paper for practical patch testing in allergic contact dermatitis in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015;26(7):598–606.

Jacob SE, Burk CJ, Connelly EA. Patch testing: another steroid-sparing agent to consider in children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25(1):81–7.

Borok J, Matiz C, Goldenberg A, Jacob SE. Contact dermatitis in atopic dermatitis children—past, present, and future. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019;56(1):86–98.

• De Groot A. Patch testing: test concentration and vehicle for 4900 chemicals. 4th ed. Wapserveen: acdegroot publishing; 2018. Detailed information for 4900 chemicals and serves as a useful standard for detailed information on patch testing various substances.

Rosmarin D, Gottlieb AB, Asarch A, Scheinman PL. Patch-testing while on systemic immunosuppressants. Dermatitis. 2009;20(5):265–70.

Wentworth AB, Davis MDP. Patch testing with the standard series when receiving immunosuppressive medications. Dermatitis. 2014;25(4):195–200.

Hoot JW, Douglas JD, Falo LD Jr. Patch testing in a patient on dupilumab. Dermatitis. 2018;29(3):164.

Kim N, Notik S, Gottlieb AB, Scheinman PL. Patch test results in psoriasis patients on biologics. Dermatitis. 2014;25(4):182–90.

Wee JS, White JML, McFadden JP, White IR. Patch testing in patients treated with systemic immunosuppression and cytokine inhibitors. Contact Dermatitis. 2010;62(3):165–9.

Johansen JD, Aalto-Korte K, Agner T, Andersen KE, Bircher A, Bruze M, et al. European Society of Contact Dermatitis guideline for diagnostic patch testing - recommendations on best practice. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;73(4):195–221.

Daunton A, Williams J. The impact of ultraviolet exposure on patch testing in clinical practice: a case–control study. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2020;45(1):25–9.

Brooks C, Kujawska A, Patel D. Cutaneous allergic reactions induced by sporting activities. Sports Med. 2003;33(9):699–708.

Bonchak JG, Prouty ME, De La Feld SF. Prevalence of contact allergens in personal care products for babies and children. Dermatitis. 2018;29(2):81–4.

Jacob SE, Herro EM. School-issued musical instruments: a significant source of nickel exposure. Dermatitis. 2010;21(6):332–3.

Tran JM, Reeder MJ. When the treatment is the culprit: prevalence of allergens in prescription topical steroids and immunomodulators [published online ahead of print, 2019 Nov 15]J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;S0190–9622(19):33110–X.

Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE. Connubial dermatitis revisited: mother-to-child contact dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2009;20(1):55–6.

de FS HM, JCS C, Lazzarini R. Evaluation of nickel and cobalt release from mobile phone devices used in Brazil. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93(1):151–3.

Anderson LE, Treat JR, Brod BA, Yu J. “Slime” contact dermatitis: case report and review of relevant allergens. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36(3):335–7.

Kullberg SA, Gupta R, Warshaw EM. Methylisothiazolinone in children’s nail polish [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 20]. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/pde.14147.

Jensen P, Hamann D, Hamann CR, Jellesen MS, Jacob SE, Thyssen JP. Nickel and cobalt release from children’s toys purchased in Denmark and the United States. Dermatitis. 2014;25(6):356–65.

Herro E, Jacob SE. P-tert-butylphenol formaldehyde resin and its impact on children. Dermatitis. 2012;23(2):86–8.

Yu J, Treat J, Chaney K, Brod B. Potential allergens in disposable diaper wipes, topical diaper preparations, and disposable diapers: under-recognized etiology of pediatric perineal dermatitis. Dermatitis. 2016;27(3):110–8.

Alberta L, Sweeney SM, Wiss K. Diaper dye dermatitis. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):e450–2

Di Altobrando A, Gurioli C, Vincenzi C, Bruni F, Neri I. Allergic contact dermatitis caused by the elastic borders of diapers. Contact Dermatitis. 2020;82(1):71–2.

Scheman A, Cha C, Jacob SE, Nedorost S. Food avoidance diets for systemic, lip and oral contact allergy: an American contact alternatives group article. Dermatitis. 2012;23(6):248–57.

Fabbro SK, Zirwas MJ. Systemic contact dermatitis to foods: nickel, BOP, and more. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2014;14(10):463.

Collis RW, Morris GM, Sheinbein DM, Coughlin CC. Expanded series and personalized patch tests for children: a retrospective cohort study 2019;1–3.

Shah KM, Goldman SE, Agim NG. Airborne contact dermatitis caused by essential oils in a child. Dermatitis. 2019;30(1):79–80.

Rundle CW, Jacob SE, Machler BC. Contact dermatitis to carmine. Dermatitis. 2018;29(5):244–9.

•• Yu J, Atwater AR, Brod B, Chen JK, Chisolm SS, Cohen DE, et al. Pediatric baseline patch test series: pediatric contact dermatitis workgroup. Dermatitis. 2018;29(4):206–12 Pediatric baseline patch test series consisting of 38 allergens recently proposed in the United States to aid in the thorough evaluation of allergic contact dermatitis in children.

Felmingham C, Davenport R, Bala H, Palmer A, Nixon R. Allergic contact dermatitis in children and proposal for an Australian paediatric baseline series. Australas J Dermatol. 2020;61(1):33–8.

Brod BA, Treat JR, Rothe MJ, Jacob SE. Allergic contact dermatitis: kids are not just little people. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33(6):605–12.

Friedmann PS. Contact sensitisation and allergic contact dermatitis: immunobiological mechanisms. In: Toxicol Lett. Vol 162. Elsevier Ireland Ltd; 2006:49–54.

Worm M, Aberer W, Agathos M, Becker D, Brasch J, Fuchs T, et al. Patch testing in children--recommendations of the German contact dermatitis research group (DKG). J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2007;5(2):107–9.

Beattie PE, Green C, Lowe G, Lewis-Jones MS. Which children should we patch test? Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32(1):6–11.

Jacob SE. Avoid the shriek with Shrek: video-distraction assist for pediatric patch testing. Dermatitis. 2007;18(3):179–80.

van Amerongen CCA, Ofenloch R, Dittmar D, Schuttelaar MLA. New positive patch test reactions on day 7-the additional value of the day 7 patch test reading. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81(4):280–7.

Chaudhry HM, Drage LA, El-Azhary RA, Hall MR, Killian JM, Prakash AV, et al. Delayed patch-test reading after 5 days: an update from the Mayo Clinic contact dermatitis group. Dermatitis. 2017;28(4):253–60.

Matiz C, Russell K, Jacob SE. The importance of checking for delayed reactions in pediatric patch testing. Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28(1):12–4.

Wilkinson DS, Fregert S, Magnusson B, Bandmann HJ, Calnan CD, Cronin E, et al. Terminology of contact dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1970;50(4):287–92.

Jacob SE, Scheman A, McGowan MA. Propylene glycol. Dermatitis. 2018;29(1):3–5.

Hannuksela M, Salo H. The repeated open application test (ROAT). Contact Dermatitis. 1986;14(4):221–7.

American Contact Dermatitis Society Contact Allergy Management Program. Available from: https://www.contactderm.org/resources/acds-camp. Accessed 4/1/2020

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Allergic Skin Diseases

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tam, I., Yu, J. Allergic Contact Dermatitis in Children: Recommendations for Patch Testing. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 20, 41 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-020-00939-z

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-020-00939-z