Abstract

Introduction

Increasing awareness and regulatory body attention is directed towards the insertion of synthetic material for a variety of surgical procedures. This review aims to assess current evidence regarding systemic and auto-immune effects of polypropylene mesh insertion in hernia repair.

Methods

The electronic literature on systemic and auto-immune effects associated with mesh insertion was examined.

Results

Foreign body reaction following mesh implantation initiates an acute inflammatory cellular response. Involved markers such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-10 and fibrinogen are increased in circulation in the presence of mesh but return to normal at 7 days post operatively. Oxidative degradation of implanted mesh is likely, but no evidence exists to support systemic absorption or resulting disease effects. Variable cytokine production in healthy hosts leading to unpredictable or overwhelming response to implanted biomaterial warrants further investigation. Clinical studies show no associated long-term systemic effects with mesh.

Conclusion

To date, there remains no evidence to link polypropylene mesh and systemic or auto-immune symptoms. Based on current evidence, the use of polypropylene mesh is supported.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There are 20 million inguinal hernia repairs performed each year worldwide making it one of the most commonly performed surgical procedures [1, 2]. The standard Lichtenstein tension free repair has significantly reduced recurrence rates and requires the use of mesh, usually in the form of polypropylene [3, 4]. There are innumerable types of mesh available which can be broadly divided according to their composition. First-generation meshes are composed of one material, most commonly polypropylene which is non-absorbable. Second-generation meshes are generally composed of polypropylene with another material and were developed to accommodate for shortcomings in tensile strength, adhesions and local reactions associated with first-generation meshes.

In a large collaboration of randomised trials, raw data from 11,000 randomised patients has shown that the use of synthetic mesh, regardless of open or laparoscopic placement, reduces the risk of hernia recurrence by 50% [5]. In addition, mesh use has actually been shown to be associated with lower rates of chronic pain compared to non-mesh techniques in a recent meta-analysis of 23 randomised controlled trials [6]. European guidelines promote the use of Lichtenstein mesh repair or laparoscopic mesh repair in primary unilateral inguinal hernia and bilateral inguinal hernias [7]. Recommendations regarding suture repair suggest that the Shouldice technique should be used if considering not using mesh. This is generally specific to scenarios when use of mesh may not be possible due to high risk of infection. Several studies have shown that for surgeons who do not specialise solely in Shouldice technique, outcomes are inferior to Lichtenstein repair [8, 9].

There is increasing patient awareness and regulatory body attention directed towards the insertion of synthetic material for a variety of surgical procedures. In 2017, the Therapeutic Goods Administration in Australia banned the use of some mesh products for use in pelvic organ prolapse. This was in response to concerns regarding under-reporting of mesh associated complications and failure of both general practitioners and specialists in recognising mesh-related problems [10]. This focused specifically on local complications of sling or tape mesh but has brought public awareness of mesh to the forefront. Successful lawsuits against surgeons and medical device manufacturers were carried out previously regarding silicone implants and associated systemic effects. An agreement via the federal district court in America in 1994 concluded that fixed settlements be paid to over 25,000 women who felt local and systemic symptoms occurred relating to implants. The breast-implant agreement ensured that set amounts were to be paid to women with specific medical conditions, including lupus, auto-immune disease and connective tissue disorders with no requirement that they show that their implants caused the disorders. Interestingly, subsequent robust studies such as a recently published 8-year follow-up involving over 1000 US hospitals found no increased systemic diseases with silicone implants [11].

A multitude of materials and mesh types exist and there is severe under reporting and lack of consistency in mesh packaging information in comparison to food packaging [12, 13]. A recent study suggests that inconsistencies in property reporting among hernia mesh brands do not provide a strong foundation for surgeons to make informed intra-operative decisions [13]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in America has issued a safety communication regarding the use of surgical meshes specifically in hernia repair [14]. Some legal firms are now investigating all hernia mesh-associated complaints and encouraging clients to come forward if they feel long-term side effects associated with their surgery. Complications now being considered to relate to mesh on consumer websites include auto-immune disease, dental problems, neurological changes, joint aches and pains and abnormal sweating [15, 16]. This review aims to assess clinical and scientific evidence regarding the association of systemic and auto-immune effects of polypropylene mesh insertion.

Methods

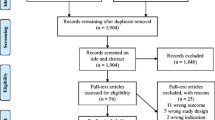

Literature published in English from January 1977 to May 2018 on systemic and autoimmune effects associated with mesh insertion was examined by electronic search (MEDLINE and the National Library of Medicine, Embase and the Cochrane Library) using the key words (“hernia” AND “mesh” AND “systemic OR auto-immune”). The search was performed independently by two reviewers who selected potentially relevant papers based on title and abstract. Additional articles were identified by cross-referencing from papers retrieved in the initial search. Due to heterogeneity of data and varied methodology, studies identified via cross-referencing describing possible mechanisms of systemic symptoms associated with polypropylene mesh insertion in surgery of any type were assessed.

Eligibility criteria

Studies including specific areas of interest that included studies relating to mesh composition, foreign body reaction, systemic inflammation, mesh degradation and individual response to mesh were included. Mesh usage and potential mechanisms for systemic effects in surgeries other than inguinal hernias were included based on their relevance. Surgery types included urological, gynaecological and pelvic floor surgery in addition to hernia surgery. There were no language restrictions. Where data was unclear, authors were contacted.

Results

Twenty-three published studies containing information relating to areas of interest such as mesh composition, foreign body reaction, systemic inflammation, mesh degradation and individual response to mesh were identified (Fig. 1). The initial search identified 84 articles. Seven full text studies were initially assessed for eligibility and a number of further studies were identified through searching the references. All studies vary significantly in scientific methods and clinical parameters recorded making homogenous systematic review impossible. No large randomised trials or data series reported any significant group of patients to suffer from systemic effects at long-term follow-up.

Foreign body reaction to mesh

Foreign body reaction following mesh implantation initiates an acute inflammatory cellular response of injury, blood-material interactions, provisional matrix formation, acute and chronic inflammation, granulation, foreign body reaction and finally fibrous capsule formation [17]. Insult to vascularized connective tissue initiates the inflammatory responses and also leads to activation of the extrinsic and intrinsic coagulation systems, complement system, fibrinolytic system, the kinin-generating system and platelets [17]. Recruitment of macrophages and monocytes to the implant site is required for the progression from initial inflammatory reaction to foreign body response. Chemokines and other chemo-attractants are responsible for guiding this process, most significantly IL-4 and IL-13, which are involved in foreign body giant cell formation [18]. Studies have demonstrated that a measurable higher systemic inflammatory marker response occurs after mesh repair compared to suture repair. Involved markers such as IL-1, IL-6, IL-10 and fibrinogen are increased in circulation in the presence of mesh [19]. With materials such as polypropylene, early resolution of the acute and chronic inflammatory responses occurs with the chronic inflammatory response composed of mononuclear cells usually lasting no longer than 2 weeks. Inflammatory responses beyond a 3-week period usually indicates an infection [17]. This is supported by other literature demonstrating a normalisation in systemic inflammatory markers at 7 days post-operatively [19].

It has been suggested that the extent of foreign body tissue reaction and associated chronic pain correlates with the amount of mesh inserted [20,21,22]. Light weight polypropylene meshes with larger pores or alternate web designs were developed to dampen the effects of foreign body reaction associated with heavy weight meshes [23, 24]. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that light weight and heavy weight meshes did not show any difference in early post-operative pain but heavy weight meshes were associated with a significantly higher incidence of chronic pain. This result remained significant for a subgroup of randomised controlled studies examining the same end-point [25]. Another recent large meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials has shown that there is no difference in chronic pain rates between mesh and non-mesh techniques [6].

Systemic and auto-immune effects of mesh

Up-regulation of systemic inflammatory markers

One hypothesis for systemic symptoms associated with mesh is that the inflammatory reaction produced locally instigates and maintains a systemic up-regulation of inflammatory mediators. All trauma associated with surgery induces a systemic inflammatory response associated with enzymatic cascades including previously mentioned coagulation factors, complement systems and altered cytokine transcription [26,27,28]. Persistent local reaction to foreign bodies can account for many mesh-related complications such as seromas and fistula formation. A persistent systemic response to mesh can hypothetically account for development of generalised symptoms in a similar fashion. A recent systematic review examined the inflammatory response in patients with mesh repair vs no mesh repair in inguinal hernia surgery [19]. Specifically, systemic levels of CRP and IL-6 were found to be higher in the immediate post-operative period in mesh repair compared to non-mesh repair in some studies [19]. This was normalised by 7 days post-operatively so does not give information regarding long-term systemic effects. Other studies have found that systemic levels of CRP and IL-6 return to similar levels between mesh and non-mesh groups after 168 h [29]. It has been suggested that normal levels of inflammatory markers following a period of 7 days suggest biological inertia of the mesh associated with excellent tissue integration [29] (Table 1).

In vivo degradation and mesh absorption

Another hypothesis to account for systemic symptoms associated with mesh is degradation and absorption of polypropylene into systemic circulation. Long-term oxidative degradation of polypropylene mesh has been suggested in explanted meshes previously (Table 1). Between 33 and 75% of polypropylene meshes can exhibit evidence of degradation at 3 years [30]. Whether or not degraded polypropylene can be absorbed systemically leading to long-term systemic symptoms or development of auto-immune disease is unclear. A number of studies have suggested that oxidative degradation does take place based on the appearance of cracks on the surface of polypropylene fibres and a thickened bark like degraded outer layer [30,31,32,33,34]. In addition to oxidative degradation, fatty acid diffusion causing long-term damage to polypropylene fibres has been hypothesised [31]. Scanning electron microscopy, infrared spectroscopy, morphological assessment along with other chemical tests and weight assessments have supported the theory that mesh and sutures are degraded in vivo. This has been found independently in different centres in human and animal models [31,32,33,34,35,36]. A recent study examining explanted polypropylene meshes which had been in place in some instances for over 11 years suggests that no oxidative degradation takes place [37]. Thames et al. found no evidence of degradation. What was previously suggested as degraded mesh and often appears as curled edges of fibres was a protein formaldehyde coating which occurs when placing explanted meshes in formalin as is frequently done at the time of removal in the operating theatre [37].

High responders

Finally, the concept of ‘high responders’ in which certain people have profound systemic reactions to implanted mesh has been suggested [38]. Polypropylene has been shown to cause a more pronounced inflammatory reaction locally when compared to polyester and ePTFE [22]. Significant research has been applied to mesh properties, associations with volume of polypropylene and recurrent inflammation and the ongoing inflammatory foreign body reaction produced. Monocytes have shown variable response to biomaterials used in surgery previously. In the context of sepsis, a marked variety of host reactions have been observed in response to the same triggers [39,40,41,42]. It has been shown that cytokine production by monocytes from healthy blood donors varies significantly when exposed to implantable biomaterials. TNF-alpha, IL-6 and IL-10 are produced in significantly different amounts according to the host. Schachtrupp et al. concluded that regarding monocyte–macrophage-derived pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, the individual was identified as an independent factor for the response to commonly used biomaterials [38] (Table 1). This warrants further investigation in the context of polypropylene mesh.

Conclusion

In the context of the current perception and attitudes towards mesh, it is critical that surgeons have a comprehensive knowledge of all clinical and scientific evidence available to them. Consenting of patients for inguinal hernia surgery requires extensive discussion around the benefits and side effects associated with polypropylene mesh. Based on current studies examining systemic effects, there is no evidence in large series to support systemic effects, backed up by systemic cytokines resolving to normal levels within 1 week of implantation. Significant evidence does exist to demonstrate some in vivo oxidative degeneration of polypropylene, but the resultant effects of this are unclear.

To support the ongoing use of mesh, however, more focused studies to disprove systemic effects may be required. Only one large population-based study designed specifically to examine the effect of mesh on systemic disease has thus far shown no association with mesh and auto-immune disease [43]. The hypotheses of abnormal host immune response, oxidative degradation with systemic absorption of polypropylene and ‘high responders’, however, are difficult to prove or disprove in the absence of well-performed clinical studies with long-term follow-up. There certainly is a significant body of scientific evidence suggesting some minimal level of degradation of polypropylene fibres when examined by electron microscopy and other techniques [31,32,33,34,35,36]. The significance of this in the context of development of systemic symptoms, however, is unclear. It is noteworthy that the majority of the studies focusing on assessment of polypropylene mesh degradation in vivo are performed following extraction and assessment in medicolegal cases.

Clinical studies to establish links between systemic disease and polypropylene have also been performed showing no association. A study based on New York State Department of Health Statewide Planning and Research Cooperative System (SPARCS) data collected over 2 years was performed examining the incidence of autoimmune/systemic inflammatory conditions in adult males following inguinal hernia surgery with mesh vs a control group undergoing colonoscopy. Over 12,000 patients who had undergone mesh inguinal hernia repair were followed up to 2 years. There was no significant difference in the development of systemic inflammatory or auto-immune diseases at 6 months, 1 year or 2 years [43]. A similar study looking at the development of auto-immune disease and conditions such as fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis following polypropylene vaginal mesh implantation for pelvic prolapse was performed. Again, no association of mesh use and auto-immune/systemic inflammatory disease was found in mesh vs control groups examining over 2000 patients [44].

The vast number of patients studied in long-term follow-up to assess recurrence and chronic pain who do not have systemic complaints, however, is evidence against the existence of systemic side effects. Case reports do describe foreign body reactions, granuloma formation in tendon repairs and urticarial rash months after the use of polypropylene sutures [45,46,47]; however, no large series exist. In order to continue to use polypropylene-based meshes to maintain optimal outcomes in inguinal hernia repair surgery, it may be necessary to perform larger studies to demonstrate their safety profile or to establish mesh registries. To establish the safety of breast implants, studies with over 10-year follow-up of more than 5000 breast implant patients were performed in Scandinavia to prove no association with malignancy [48]. Over 40,000 patients were prospectively followed in North America to outrule an association between connective tissue disease and breast implants [49].

Historically, the fact that no evidence exists to prove an association between mesh and systemic disease does not provide medicolegal protection. More importantly, it may become increasingly common for patients to refuse mesh-based hernia repairs based on consumer sites associating mesh with systemic side effects. Further scientific data regarding long-term up-regulation of inflammatory mediators beyond the first post-operative week in higher volumes of patients may be useful. Large clinical studies focusing on systemic complaints at long-term follow-up and the use of registries for all patients in which mesh is inserted would further support the appropriate use of mesh in hernia repairs and other surgeries.

References

Rutegård M, Gümüsçü R, Stylianidis G, Nordin P, Nilsson E, Haapamäki M (2018) Chronic pain, discomfort, quality of life and impact on sex life after open inguinal hernia mesh repair: an expertise-based randomized clinical trial comparing lightweight and heavyweight mesh. Hernia 22(3):411–418

Dabbas N, Adams K, Pearson K, Royle G (2011) Frequency of abdominal wall hernias: is classical teaching out of date? JRSM Short Rep 2(1):5

Beets GL, Oosterhuis KJ, Go PM, Baeten CG, Kootstra G (1997) Long term followup (12-15 years) of a randomized controlled trial comparing Bassini-Stetten, Shouldice, and high ligation with narrowing of the internal ring for primary inguinal hernia repair. J Am Coll Surg 185:352–357

Amid PK (2005) Groin hernia repair: open techniques. World J Surg 29(8):1046–1051

Collaboration EUHT (2002) Repair of groin hernia with synthetic mesh: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Surg 235(3):322–332

Öberg S, Andresen K, Klausen TW, Rosenberg J (2018) Chronic pain after mesh versus nonmesh repair of inguinal hernias: a systematic review and a network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Surgery. 163:1151–1159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2017.12.017

Simons MP, Aufenacker T, Bay-Nielsen M, Bouillot JL, Campanelli G, Conze J, de Lange D, Fortelny R, Heikkinen T, Kingsnorth A, Kukleta J, Morales-Conde S, Nordin P, Schumpelick V, Smedberg S, Smietanski M, Weber G, Miserez M (2009) European hernia society guidelines on the treatment of inguinal hernia in adult patients. Hernia 13(4):343–403

Danielsson P, Isacson S, Hansen MV (1999) Randomised study of Lichtenstein compared with Shouldice inguinal hernia repair by surgeons in training. Eur J Surg 165(1):49–53

Amato B, Moja L, Panico S, Persico G, Rispoli C, Rocco N, Moschetti I (2012) Shouldice technique versus other open techniques for inguinal hernia repair. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (4):CD001543. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001543.pub4

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. www.safetyandquality.gov.au/our-work/transvaginal-mesh/. Last accessed 02/03/2018

Singh N, Picha GJ, Hardas B, Schumacher A, Murphy DK (2017) Five-year safety data for more than 55,000 subjects following breast implantation: comparison of rare adverse event rates with silicone implants versus National Norms and saline implants. Plast Reconstr Surg 140(4):666–679

Zhu LM, Schuster P, Klinge U (2015) Mesh implants: an overview of crucial mesh parameters. World J Gastrointest Surg 7(10):226–236

Kahan L, Blatnik J (2018) Critical under-reporting of hernia mesh properties and development of a novel package label. J Am Coll Surg 226(2):117–125

FDA (2014) Safety Communications-surgical mesh: FDA safety communication. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/AlertsandNotices/. Last accessed 03/03/2018

Akre J (2014) Autoimmune diseases and surgical mesh—causation or correlation? Available from: http://meshmedicaldevicenewsdesk.com/autoimmune-diseases-and-surgical-mesh-causation-or-correlation

https://hollislawfirm.com/case/hernia-mesh-lawsuit/ Last accessed 03/03/2018

Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT (2008) Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Semin Immunol 20(2):86–100

Gerard C, Rollins BJ (2001) Chemokines and disease. Nat Immunol 2(2):108–115

Kokotovic D, Burcharth J, Helgstrand F, Gögenur I (2017) Systemic inflammatory response after hernia repair: a systematic review. Langenbeck's Arch Surg 402(7):1023–1037

Baylón K, Rodríguez-Camarillo P, Elías-Zúñiga A, Díaz-Elizondo JA, Gilkerson R, Lozano K (2017) Past, present and future of surgical meshes: a review. Membranes 7:47

Öberg S, Andresen K, Rosenberg J (2017) Absorbable meshes in inguinal hernia surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Innov 24(3):289–298

Klinge U, Klosterhalfen B, Muller M, Schumpelick V (1999) Foreign body reaction to meshes used for the repair of abdominal wall hernias. Eur J Surg 165(7):665–673

Alfieri S, Amid PK, Campanelli G, Izard G, Kehlet H, Wijsmuller AR, di Miceli D, Doglietto GB (2011) International guidelines for prevention and management of post-operative chronic pain following inguinal hernia surgery. Hernia 15:239–249

Massaron S, Bona S, Fumagalli U, Valente P, Rosati R (2008) Long-term sequelae after 1,311 primary inguinal hernia repairs. Hernia. 12(1):57–63

Li J, Ji Z, Cheng T (2012) Lightweight versus heavyweight mesh in inguinal hernia repair: a meta-analysis. Hernia. 16(5):529–539

Klosterhallfen B, Klinge U, Hermanns B, Schumpelick V (2000) Pathology of traditional surgical nets for hernia repair after long-term implantation in humans. Chirurg 71:43–51

O'Dwyer MJ, Owen HC, Torrance HD (2015) The perioperative immune response. Curr Opin Crit Care 21:336–342

Arnould JP, Eloy R, Weill-bousson M et al (1977) Resistance et tolerance biologique de 6 protheses inertes utilises dans la reparation de la paroi abdominale. J Chir 113:85–100

Di Vita G, Milano S, Frazzetta M, Patti R, Palazzolo V, Barbera C, Ferlazzo V, Leo P, Cillari E (2000) Tension-free hernia repair is associated with an increase in inflammatory response markers against the mesh. Am J Surg 180(3):203–207

Ostergard DR (2010) Polypropylene vaginal mesh grafts in gynecology. Obstet Gynecol 116(4):962–966

Clavé YH, Hammou JC, Montanari S, Gounon P, Clavé H (2010) Polypropylene as a reinforcement in pelvic surgery is not inert: comparative analysis of 100 explants. Int Urogynecol J 21:261–270

Liebert TC, Chartoff RP, Cosgrove SL, McCuskey RS (1976) Subcutaneous implants of polypropylene filaments. J Biomed Mater Res 10:939–951

Imel A, Malmgren T, Dadmun M, Gido S, Mays J (2015) In vivo oxidative degradation of polypropylene pelvic mesh. Biomaterials. 73:131–141

Iakovlev VV, Guelcher SA, Bendavid R (2015) Degradation of polypropylene in vivo: a microscopic analysis of meshes explanted from patients. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 105:237–248. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm.b.33502

Costello C, Bachman S, Ramshaw B, Grant S (2007) Materials characterisation of explanted polypropylene meshes. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 83(1):44–49

Lefranc O, Bayon Y, Montanari S, Gravagna P, Thérin M (2011) Reinforcement materials in soft tissue repair: key parameters controlling tolerance and performance – current and future trends in mesh development. New Tech Genit Prolapse Surg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-84882-136-1_25

Thames SF, White JB, Ong KL (2017) The myth: in vivo degradation of polypropylene-based meshes. Int Urogynecol J 28(2):285–297

Schachtrupp AV, Klinge K, Junge R, Rosch RS, Bhardwaj C, Schumpelick V (2003) Individual inflammatory response of human blood monocytes to mesh biomaterials. Br J Surg 90:114–120

Bienvenu J, Monneret G, Fabien N, Revillard JP (2000) The clinical usefulness of the measurement of cytokines. Clin Chem Lab Med 38:267–285

Schraut W, Wendelgass P, Calzada-Wack JC, Frankenberger M, Ziegler-Heitbrock HW (1997) TNF gene expression in monocytes of low and high responder individuals. Cytokine 9:206–211

Schroder J, Kahlke V, Book M, Stuber F (2000) Gender differences in sepsis: genetically determined? Shock 14:307–310

Matthews JB, Green TR, Stone MH, Wroblewski BM, Fisher J, Ingham E (2000) Comparison of the response of primary human peripheral blood mononuclear phagocytes from different donors to challenge with model polyethylene particles of known size and dose. Biomaterials 21:2033–2044

Chughtai B, Thomas D, Mao J, Eilber K, Anger J, Clemens JQ, Sedrakyan A (2017) Hernia repair with polypropylene mesh is not associated with an increased risk of autoimmune disease in adult men. Hernia. 21(4):637–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-017-1591-1

Chughtai B, Sedrakyan A, Mao J, Eilber KS, Anger JT, Clemens JQ (2017) Is vaginal mesh a stimulus of autoimmune disease? Am J Obstet Gynecol 216(5):495

Al-Qattan MM, Al-Zahrani K, Kfoury H, Al-Qattan NM, Al-Thunayan TA (2016) A delayed foreign body granuloma associated with polypropylene sutures used in tendon transfer. A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 26:118–120

Al-Qattan MM et al (2015) A delayed allergic reaction to polypropylene suture used in flexor tendon repair: case report. J Hand Surg 40:1377–1381

Cajigas I, Burks SS, Gernsback J, Fine L, Moshiree B, Levi AD (2015) Allergy to Prolene sutures in a Dural graft for Chiari decompression. Case Rep Med:583570

Lipworth L, Tarone RE, Friis S, Ye W, Olsen JH, Nyren O, McLaughlin JK (2009) Cancer among Scandinavian women with cosmetic breast implants: a pooled long-term follow-up study. Int J Cancer 124:490–493

Lee IM, Cook NR, Shadick NA, Pereira E, Buring JE (2011) Prospective cohort study of breast implants and the risk of connective-tissue diseases. Int J Epidemiol 40:230–238

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Clancy, C., Jordan, P. & Ridgway, P.F. Polypropylene mesh and systemic side effects in inguinal hernia repair: current evidence. Ir J Med Sci 188, 1349–1356 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-019-02008-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-019-02008-5