Abstract

Background

There is extensive focus on the rising costs of healthcare. However, for patients undergoing cancer treatment, there are additional personal costs, which are poorly characterised.

Aim

To qualify indirect costs during anti-cancer therapy in a designated Irish cancer centre.

Methods

An anonymous questionnaire collected demographic data, current work practice, and personal expenditure on regular and non-regular indirect costs during treatment. Differences between groups of interest were compared using the Mann–Whitney U test.

Results

In total, there were 151 responders of median age 58 years; 60 % were female and 74 % were not working. Breast cancer (29 %) was the most frequent diagnosis. Indirect costs totalled a median of €1138 (range €21.60–€7089.84) per patient, with median monthly outgoings of €354. The greatest median monthly costs were hair accessories (€400), transportation (€65), and complementary therapies (€55). The majority (74 %) of patients used a car and median monthly fuel expenditure was €31 (range €1.44–€463.32). Women spent more money during treatment (€1617) than men (€974, p = 0.00128). In addition, median monthly expenditure was greater for those less than 50 years old (€1621 vs €1105; p = 0.04236), those who lived greater than 25 km away (€2015 vs €1078; p = 0.00008) and those without a medical card (€2023 vs €961; p = 0.00024).

Conclusion

This study highlights the need for greater awareness of indirect expenditures associated with systemic anti-cancer therapy in Ireland.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the era of precision medicine and immunotherapy, advances in cancer treatments have come at a significant price to the healthcare system. However, the personal cost to an individual patient with cancer is less well documented and harder to quantify. Despite government subsidies for the majority of a patient’s cancer therapy, there is minimal support for the multiple indirect costs occurring during their cancer journey with almost all reporting some financial challenges [1–3]. Sources of these additional costs include frequent transportation to centralised centres of excellence, as well as requirements for parking, childcare, and supportive medications [4–6].

The identification of sources of expenditure could improve patient awareness, education, and financial advice prior to commencing their cancer treatment, as well as potentially highlighting areas that could benefit from increased local and national support. To address both these issues, this research set out to quantify and qualify the personal cost to patients receiving outpatient anti-cancer therapy at a designated Irish cancer centre.

Methods

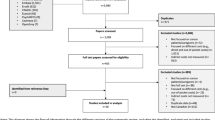

Patients

Patients, 18 years and older, were invited to voluntarily complete an anonymous questionnaire during their day ward visit for oral, intravenous and subcutaneous anti-cancer medicines. Institutional approval for carrying out this questionnaire was granted through the audit department. All data were electronically recorded on a password-protected excel spreadsheet for the statistical analysis. No personal patient information was collected.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire collected patient-reported clinical and demographic data, such as age, gender, and cancer diagnosis. Patients were also asked to report their knowledge on the duration of their anti-cancer treatment, their average monthly attendances to the day ward, and the average number of hours spent at the day ward. Further information included possession of a medical card, current work practice, and schedule and whether patients deemed anti-cancer medicines the cause of any changes to work agenda.

The second part of the questionnaire focused on factors known to be associated with increased personal cost during medical treatment. It gathered information upon one-off costs (hair accessories, attendances to emergency departments and general practitioners (GPs), and any religious or non-religious travels) and recurrent monthly spending (transportation costs, parking, need for childcare, use of complementary therapies, monthly prescribed medication cost, and food and drink during day ward visits).

Patients reported the mode of transport as well as distance travelled to the day ward. For patients attending by car, a validated formula of €0.46/km was utilised to quantify the cost of fuel over these distances. This formula was taken from the Irish Revenue website as the intermediate value for the standard employee travel expenses [7].

Analysis

Reported expenditures and estimated duration of anti-cancer therapy allowed a monthly median cost per patient to be quantified as well as a total cost for the entirety of the anti-cancer treatment. Median total cost for the duration of therapy was compared between groups of interest using the Mann–Whitney U test. Data testing demonstrated an approximate Gaussian distribution of the data. The value of U (test statistic) where relevant was converted to the appropriate z value, and the associated values of p were derived using actuarial tables. A 1.25 % significance level (p value less than 0.0125) was used in analysing results which included all costs where four different null hypotheses were applied to the data. In other words, the significance level usually applied (5 %) was divided by 4—the number of null hypotheses tested. A 5 % significance level was applied to the analysis of costs, which excluded the cost of hair accessories, as this was only analysed by gender.

Results

Patient demographics

Over a 3-week period, 151 patients were included, estimated as 48 % of the total population attending the Oncology Day Ward. The median age of respondents was 58 (range 20–79) years, most (60 %) were female, and the largest single group (29 %) had breast cancer (Table 1).

Hospital visits

Three quarters of patients estimated their expected duration of treatment to be a median of 6 months with the remaining patients uncertain as to their treatment length (Table 1). Twenty-one (14 %) reported that they would be receiving cancer treatment indefinitely and 11 % stated that they did not know the planned duration of their treatment. Patients attended the day ward a median of three times per month. Almost two-thirds of patients possessed medical cards.

Distance from hospital

The median distance travelled by patients was 16 km (range 0.8–321.8 km) to attend the cancer centre (Fig. 1). Over a third of respondents lived beyond 25 km from the hospital (n = 48) and a small but noteworthy 6 % of the respondents lived beyond 100 km of the oncology day ward.

Current work practices

At the time of the completion of the questionnaire, the majority (74 %) of patients were not working (Table 2). Fourteen (9 %) patients were self-employed, of whom 7 (50 %) were working during treatment. In contrast, only 19 % of patients who were not self-employed (n = 137) reported to be working (Fig. 2). Over half of all patients (53 %, n = 80) did not consider anti-cancer therapy the reason for not working, however, of this group of respondents, 38 % were retired and a further 35 % were still working in some capacity.

Additional personal cost during medical treatment

The median additional cost for each individual patient was €354 per month (range €4–€5149). The median total cost for the estimated complete duration of cancer therapy was €1138 per patient (range €21.60–€7089.84).

The median total cost during treatment was €1617 for women, compared with €974 for men (Table 3), and this difference was statistically significant at the 1.25 % significance level (p = 0.00128). This was primarily because of hair accessories purchased by female patients, as removing the cost of hair accessories from this total median cost minimised the difference between sexes to €1187, which was statistically insignificant (p = 0.08186). Notably, median expenditure was greater for those less than 50 years of age (€1621) compared with older respondents (€1105) (p = 0.04236). As might be expected, median expenditure was statistically greater for those patients that lived further than 25 km away from the hospital (€2015) vs those within 25 km (€1078), (p = 0.00008). Patients with medical cards also spent a statistically significant lower amount than those without (€961 vs €2023, p = 0.00024).

Specific expenditure

Patients reported a total median spend of €100 (range €0–€5000) for one-off items, such as wigs and other hair accessories, as well as unexpected attendances to the emergency department or their GP and spiritual or religious trips or retreats (Fig. 3).

Recurring costs totalled a median of €160 (range €4–€864) each month. These included transportation, childcare, complementary therapies, prescription medicines, and consumables (Fig. 4).

One-off costs

Hair accessories

Patients spent a median of €400 (range €0–€2500) on hair accessories for treatment-related alopecia including wigs, headscarves, and hats. Notably, almost half the respondents did not spend any money on hair accessories (n = 72, 48 %), although the majority of these patients were men (n = 47, 65 %). Of the 76 (50 %) respondents that bought hair accessories, 62 (82 %) required at least one wig. Only one man bought a wig.

Attendances to GP and emergency departments

Sixty-nine (46 %) patients reported attending their GP and 20 (13 %) patients attended emergency departments during their cancer treatment. Patients spent a mean of €63 and €82.50 on GP and emergency attendances respectively.

Religious pilgrimages/spiritual retreats

One hundred and twenty two (81 %) respondents stated that they would not consider spending money on a religious pilgrimage. Eight (5 %) patients had been on one of these retreats, at a median cost of €1000 (range €500–€3000). One hundred and thirty four (89 %) had no interest in non-religious spiritual retreats. Six (4 %) patients had or continued to attend a non-religious centre, at a median cost of €300 (range €50–€5000). Seventeen (11 %) and 7 (4 %) patients were considering spending money on religious and non-religious retreats, respectively.

Recurrent costs

Transportation

The median monthly total transport cost for each patient was €65 (range €0–€494.70). The majority (74 %) of patients used a car to attend hospital appointments, and parking was required by 113 (75 %) at a median monthly cost of €24 (range €0–€125). Using reported distance travelled, median monthly fuel expenditure was estimated at €31 (range €1.44–€463.32).

Thirty-nine patients (26 %) travelled using alternative modes of transport: 22 bus, 14 taxi, 3 charity taxi/bus, 3 walked, 1 patient cycled, and 2 patients reported using other modes of transport. Patients sometimes used more than one mode of alternative transportation. Alternative non-car modes of transport cost a median of €9.50 per visit (range €0–€100 per visit) and a median monthly cost of €25 (range €0–€210).

Childcare

Only thirty (20 %) respondents, of median age 45 years, needed to arrange childcare to attend the oncology day ward. However, the majority (77 %) of these patients did not spend money on childcare, as support was predominantly given by family (n = 15), neighbours, and friends (n = 3). In particular, grandparents took on the majority burden (n = 6), followed by the patient’s partner (n = 2), an elder child (n = 1), and patient’s siblings (n = 1). Occasionally official child-minding services (n = 2) or combined childcare services with family/friends (n = 6) were necessary. This group spent a median of €38 (range €20–€144) for childcare to attend the day ward for treatment which equated to €90 monthly.

Complementary therapies

Thirty-five (23 %) respondents spent a mean of €83.38 on complementary therapies, including dietary changes (n = 18), herbs and/or multivitamins (n = 5), reflexology (n = 5), faith healers (n = 4), counselling (n = 3), massage (n = 3), and yoga/Pilates (n = 3). Most dietary changes involved either juicing or switching to organic food produce.

Discussion

This questionnaire-based study revealed the high personal cost of attending for anti-cancer therapy (median expenditure €1138 per patient). The breakdown of expenditure revealed that the most expensive once-off payments were religious pilgrimages (median cost €1000), hair accessories (median cost €400), and spiritual retreats or non-religious groups (median cost €300) (Fig. 3). Transportation (median €65 per month, range €0–€494.70) inclusive of fuel, parking and alternative modes of transport, and complementary therapies (median cost €55 per month) made up the most costly recurring monthly spend (Fig. 4). However, only 5 % of patients had attended a religious pilgrimage and 4 % of respondents reported attending a non-religious spiritual centre. In comparison, half of all patients were required to purchase hair accessories for treatment-induced alopecia. Importantly, this research identified vulnerable groups at highest risk of increased financial demands, such as those with children, those living in remote areas, the self-employed and the younger cohort of patients (Table 3).

This study also highlighted changes to work practices that can occur as a result of anti-cancer treatment (Table 2). Only 26 % of patients were actively working with approximately half fulltime and half parttime. The remaining majorities were not working, but it is noteworthy that over one-third were retired.

In 2010, the National Cancer Registry of Ireland (NCRI) quantified the personal cost of anti-cancer therapy. The published dissertation “The Financial Impact of a Cancer Diagnosis” revealed 55 % of Irish patients used savings to support their time receiving treatment [8]. More recently, the Irish Cancer Society identified a monthly cost of €862 in a nationwide online survey of a smaller cohort of 409 patients [9]. This included patient’s loss of income, health insurance, and additional bills in addition to the indirect costs also assessed in this research, Interestingly, it found much higher costs for the transportation of €287 per month. This was partly due to a higher proportion of rural respondents travelling farther distances. In comparison, transportation costs reported in this study reflected an urban catchment area. Internationally, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and the United Kingdom-based Macmillan Cancer Foundation have similarly published on this challenging problem [10, 11]. Our research is consistent with international publications, but it differs from other national work in this field, as it includes a broad range of cancer types and reflects the “real world” nature of the oncology day ward. In contrast, the NCRI data focused upon breast, prostate, and lung cancers only. Our study also reports details of complementary therapy costs, dietary changes, and religious or spiritual trips taken during cancer treatment, which have often been omitted from the previous studies.

In Ireland, cancer patients are aided by the receipt of medical cards as well as a number of charitable schemes, where patients can apply for hardship funds, transport support, and financial aid. Most schemes, however, are subjected to means testing and are often only available to the most vulnerable groups. This work highlights areas that would benefit from support, subsidy, or funding. In particular, transportation, including parking, is a significant problem area. One practical solution would be for hospitals to arrange subsidised or free car parking for patients regularly attending the oncology day ward. In addition, it would likely benefit patients to have an early introduction to hospital-based financial advisors that could guide cancer patients on budgeting techniques and financial planning to minimise the fiscal impact upon themselves and their families.

There are a number of limitations to this study. In particular, the results rely upon patient-reported expenditure and, as such, may contain inaccuracies, oversights, and imprecisions. The questionnaire is obviously open to selection bias as regard the patients who are more inclined to complete the questionnaire. It is estimated that approximately half the possible patients voluntarily completed the questionnaire. This is apparent in the female preponderance and younger age of respondents than might be truly reflective of the day ward attendances (Table 1). The questionnaire was unable to exhaustively assess all smaller potential costs upon patients for practical reasons: use of road tolls, cost of other varied supportive care, such as mouthwashes, stoma bags, high sun protection factor skin care, mastectomy prostheses, swimwear and brassieres as well as new clothing for weight increases or decreases. Whether patients had private health insurance was not collected on the questionnaire. This obviously has implications for reimbursement of various aspects of personal expenditure. This research did not explore the impact on savings, lost income, and need for borrowings due to concerns that a more extensive, and burdensome questionnaire might preclude voluntary completion of the survey. Similarly, lost days due to sick leave, disability, and the overall price to the taxpayer were not assessed. Finally, the cost implications on the family unit were not assessed, such as family members taking time off work with resultant lost income, use of sick/holiday leave, as well as potential transportation costs and childcare arrangements for other family members.

This work sets out to quantify and qualify the high personal indirect costs during systemic treatment and has identified problem areas that could be targeted to reduce current patient spending. Potential solutions include the establishment of hospital-based financial advisors, improved education and awareness for both patients and physicians, and early encouragement to budget and plan. Furthermore, additional government, hospital or charitable subsidies to the more common sources of expenditure, such as travel and parking, would be welcomed in the future.

References

Gordon L, Scuffham P, Hayes S et al (2007) Exploring the economic impact of breast cancers during the 18 months following diagnosis. Psychooncology 16:1130–1139

Arndt V, Merx H, Stegmaier C et al (2004) Quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer 1 year after diagnosis compared with the general population: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol 22:4829–4836

Arndt V, Merx H, Stegmaier C et al (2005) Persistence of restrictions in quality of life from the first to the third year after diagnosis in women with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 23:4945–4953

Moore KA (1999) Breast cancer patients’ out-of-pocket expenses. Cancer Nurs 22:389–396

Pearce S, Kelly D, Stevens W (2001) “More than just money”—widening the understanding of the costs involved in cancer care. J Adv Nurs 33(3):371–379

Longo CJ, Fitch M, Deber RB et al (2006) Financial and family burden associated with cancer treatment in Ontario, Canada. Support Care Cancer 14:1077–1085

Irish Employees’ Motoring/Bicycle Expenses-IT51 (2016) http://www.revenue.ie/en/tax/it/leaflets/it51.html. Accessed 13 Jul 2016

L Sharp, A Timmons (2010) The financial impact of a cancer diagnosis. http://hse.openrepository.com/hse/handle/10147/188292. Accessed 13 Jul 2016

Irish Cancer Society (2016) The real cost of cancer. Research conducted by Millward Brown 2015. http://www.cancer.ie/sites/default/files/content-attachments/the_real_cost_of_cancer_report_final.pdf. Accessed 13 Jul 2016

Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ et al (2009) American society of clinical oncology guidance statement: the cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol 27(23):3868–3874

Macmillan (2012) Cost of cancer campaign. http://www.macmillan.org.uk/documents/getinvolved/campaigns/costofcancer/thecostofcancercampaignreport.pdf. Accessed 13 Jul 2016

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the patients and their families for taking part in this research and completing the questionnaire.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study has no funding to declare.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Collins, D.C., Coghlan, M., Hennessy, B.T. et al. The impact of outpatient systemic anti-cancer treatment on patient costs and work practices. Ir J Med Sci 186, 81–87 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-016-1483-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-016-1483-x