Abstract

Background

Treatment of pilonidal sinus disease is controversial. Many claim policy of marsupialisation and healing by secondary intention. This is demanding in terms of nursing care and time lost from work.

Aims

To examine outcome of excision and primary closure of chronic pilonidal disease on recurrence rate and patient’s daily activities.

Patients and methods

One hundred and fourteen consecutive elective patients who had excision and primary closure of pilonidal sinus disease were reviewed. The demographic data and the post-operative outcome were studied.

Results

The recurrence of pilonidal sinus was noted in 9% of patients, wound breakdown occasioning delayed healing in 9%, patients able to drive by day 16 on average. The mean time to return to work was 20.5 days; duration of analgesia, 2.4 days; and duration of antibiotic treatment, 4.7 days.

Conclusion

Excision and primary closure of chronic pilonidal sinus has low recurrence rate with early return to activities. Primary closure appears to be a cost-effective option for uncomplicated pilonidal sinus disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pilonidal sinus disease is a significant cause of morbidity and absence from work [1]. Its management is controversial as reflected in the range of treatment options available such as, excision with primary closure, cleft lift [2], transposed rhomboid flap [3], Limberg flap [4], VY fasciocutaneous flap [5] or Z-plasty [6]. But many surgeons advocate marsupialisation or leaving the defect open to heal by secondary intention in all cases, citing the high incidence of recurrence after primary closure to support this policy [7–9]. This approach is time consuming, taking up to a year to close and is costly in time and resources and is unsatisfactory for patients. Primary closure would clearly be superior if it could be performed with a sufficiently low-recurrence rate.

The aim of this study was to examine the outcome of a policy of excision and primary closure of all cases of chronic pilonidal sinus on recurrence rate and patient’s daily activities.

Patients and methods

A retrospective study was conducted on a consecutive series of 114 patients presenting with pilonidal sinus disease under one consultant surgeon in a Dublin academic surgical department over a 5-year period from 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2005 and followed up for 3 years. Patients with acutely infected pilonidal sinuses were excluded from the study.

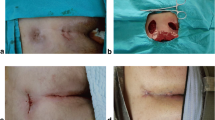

Patients underwent a standardised operative technique. All procedures were performed under general anaesthesia in the prone position. The first dose of an intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotic (co-amoxyclav) was administered on induction of anaesthesia. The operative field was prepared by separating the buttocks with an adhesive tape and the area of disease was waxed (Fig. 1). The incisions were marked. The area was infiltrated with Bupivacaine 0.5% with adrenaline 1 in 200,000 to provide both intra-operative haemostasis and post-operative analgesia.

The extent of the sinus tract(s) was delineated by infusing each sinus opening with diluted methylene blue dye, which also demarcated any deep secondary extension (Fig. 2). The sinus was resected en bloc through a longitudinal elliptical incision. The incision was extended to excise any lateral extensions. This sometimes required Z-shaped reconstruction. Dissection was performed using electrocautery, paying particular attention to the areas of methylene blue dye distribution to ensure full en bloc excision of the entire sinus tract (Fig. 3). Haemostasis was secured and the dead space was obliterated by deep-tension sutures (0 polypropylene) encompassing the entire dead space up to the sinus cavity. Interrupted superficial sutures (4/0 polypropylene) were used for skin closure (Fig. 4). The deep-tension sutures were then tied over rolled gauze to prevent the tension suture material from cutting through the skin (Fig. 5). Further long-acting local anaesthetic (Bupivacaine 0.5%) was infiltrated into the wound for local pain control prior to reversal of anaesthesia.

The tension sutures were removed on day 10 post-operatively and the superficial skin sutures were removed on day 14. Follow-up was by review in the outpatient departments and telephone survey.

Results

One hundred and fourteen consecutive patients presenting with pilonidal sinus disease underwent elective excision and primary closure during this 5-year period. There were 71% males (n = 81). The mean age was 26 years (range 14–51). Forty-four patients had previously undergone incision and drainage of a pilonidal abscess prior to surgery. The mean duration for post-operative analgesia requirement was 2.4 days (range 1–10 days) with the exception of two patients who required long-term use of analgesia. All patients were treated with antibiotics following surgery for an average of 5 days (range 2–7 days) depending on the extent of the sinus and the degree of underlying infection encountered. The details of patients’ occupation are illustrated in Table 1.

Of the patients, 69% (n = 79) experienced no post-operative complications, while 31% (n = 35) patients had at least one complication including superficial wound infection in 13% (n = 15), wound breakdown in 9% (n = 10), and recurrence of sinus in ten patients (9%) (Fig. 6). The sinuses that recurred were more likely to be deeper, longer and more complex than those that healed uneventfully. Treatment of recurrent pilonidal sinuses was by marsupialisation or further primary closure. Of the ten recurrences, six required one further operation, three required two operations and one required three further procedures.

When questioned about the time before being able to drive and return to work or study, 82 patients who normally drove were unable to drive for an average of 16 days (4–7 days). The average time required to return to work or study was 20.5 days (range 7–90 days).

Discussion

Excision with primary wound closure or excision and wound healing by secondary intention with or without marsupialisation are the two principal surgical options for pilonidal sinus disease. The best treatment option remains controversial [7, 10]. The differences between these two techniques relate to the time it takes for the wound to heal and the rate of wound breakdown and recurrence.

Although primary closure has a slightly higher infection rate (due to the presence of a closed potential cavity after resection), it carries the potential for quicker wound healing. In this study, 9% of patients suffered wound breakdown, which healed by secondary intention and 9% developed recurrence. This compares well with published series [11]. Recurrence rates following excision and primary closure vary in the literature and range between 11 and 42%. Peterson et al. reported wound breakdown and infection in 11.1% of 1,731 patients in a survey of patients treated with excision and primary closure.

Wounds that failed to heal after primary closure were allowed to heal by secondary intention. The data do not show longer time disability in this group compared with those with open wound management or treated with marsupialisation [8]. Excision and primary closure is associated with less morbidity and is more cost-effective than excision and open packing [12]. Wounds that are left open take, on average, 8–10 weeks to heal [13] but some take much longer than this. These open wounds require aggressive management with frequent dressing changes and close observation by both patient and surgeon. The overall costs, both direct and indirect (inpatient care, dressing clinic appointments, time off work) of this strategy are therefore higher than with primary closure.

This procedure is now performed as a day case with no obvious increase in recurrence rate from when it was performed as an in-patient, which was the chief concern and which prompted restriction of activity for the duration of healing period. It is unclear for how long patients should limit mobility but it would seem prudent to advise restriction while the sutures are in place to discourage haematoma or seroma formation, which might promote recurrence.

In conclusion, a policy of excision and primary closure using deep-tension suture over a rolled wound pack can be performed with a low expected recurrence rate and should be considered the treatment of choice for all pilonidal sinuses leaving marsupialisation or more complex flap procedures for selected recurrent disease.

References

Chintapatla S, Safarani N, Kumar S, Haboubi N (2003) Sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus: historical review, pathological insight and surgical options. Tech Coloproctol 7(1):3–8

Bascom J, Bascom T (2007) Utility of cleft lift procedure in refractory pilonidal disease. AJS 193(5):606–609

Arumugam PJ, Chandrasekaran TV, Morgan AR, Beynon J, Carr ND (2003) The rhomboid flap for pilonidal disease. Colorectal Dis 5(3):218–221

Erylimaz R, Sahin M, Alimoglu O, Dasiran F (2003) Surgical treatment of sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus with the Limberg transposition flap. Surgery 134(5):745–749

Schoeller T, Wechselberger G, Otto A, Papp C (1997) Definite surgical treatment of complicated recurrent pilonidal disease with a modified fasciocutaneous V-Y advancement flap. Surgery 121(3):258–263

Sharma PP (2006) Multiple Z-Plasty in pilonidal sinus-A new technique under local anaesthesia. World J Surg 30(12):2261–2265

Menzel T, Dorner A, Cramer J (1997) Excision and open wound treatment of pilonidal sinus. Rate of recurrence and duration of work incapacity. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 122(47):1447–1451

Sondenaa K, Andersen E, Soreide JA (1992) Morbidity and short term results in a randomised trial of open compared with closed treatment of chronic pilonidal sinus. Eur J Surg 158(6–7):351–355

Perruchoud C, Vuilleumier H, Givel JC (2002) Pilonidal sinus: how to choose between excision and open granulation versus excision and primary closure? Study of a series of 141 patients operated on from 1991 to 1995. Swiss Surg 8(6):255–258

De Caestecker JD, Mann B, Castellanos A, Straus J (2006) Pilonidal disease. In: Lundberg G (ed). E Medicine

Peterson S, Koch R, Stelzner S, Wendlandt T-P, Ludwig K (2002) Primary closure techniques in chronic pilonidal sinus. A survey of the results of different surgical approaches. Dis Colon Rectum 45:1458–1465

Fuzun M, Bakir H, Soylu M, Tansug T, Kaymak E, Harmancioglu O (1994) Which technique for treatment of pilonidal sinus—open or closed? Dis Colon Rectum 37(11):1148–1150

Kronberg I, Christensen KI, Zimmerman-Nielson O (1986) Chronic pilonidal disease: a randomised trial with complete three year follow up. Br J Surg 72:303–304

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gilani, S.N.S., Furlong, H., Reichardt, K. et al. Excision and primary closure of pilonidal sinus disease: worthwhile option with an acceptable recurrence rate. Ir J Med Sci 180, 173–176 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-010-0532-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-010-0532-0