Abstract

Introduction

Paraneoplastic neurological disorders are rare complications of breast carcinoma. Lambert–Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome (LEMS) is most commonly associated with small cell lung cancer. However, a combination of LEMS and subacute cerebellar degeneration as paraneoplastic syndromes is extremely rare, and has never been described in association with breast cancer.

Case

We report for the first time an unusual association of LEMS and paraneoplastic subacute cerebellar degeneration with breast carcinoma.

Conclusion

In patients with atypical LEMS, when there is no evidence of respiratory malignancy, breast cancer should be included in the differential diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Paraneoplastic syndromes are the rarest neurological complications in patients with cancer [1]. Lambert–Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome (LEMS) is an uncommon paraneoplastic neurological disorder (PND) that is classically described in patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC) [1]. PNDs that are mainly associated with breast cancer are subacute cerebellar degeneration, retinopathy, opsoclonus-myoclonus syndrome and Stiff-man syndrome [2]. A combination of LEMS and paraneoplastic subacute cerebellar degeneration (PSCD) has been reported in association with lung cancer in the past [3, 4], but not with breast carcinoma. Here, we report an unusual presentation of breast cancer with concomitant LEMS and PSCD. Consent was obtained from the patient prior to publication of this case.

Case

A 59-year-old, life-time smoker female was diagnosed with a low-to-intermediate grade invasive ductal carcinoma associated with DCIS (pT1cN1) in her right breast behind the nipple-areola complex (ER+/PR+). She underwent a wide local excision and a level II axillary lymph node clearance (1 out of 15 lymph nodes contained metastasis).

On admission for the axillary clearance the patient reported a 4-week history of increased tiredness, which had coincided with her diagnosis of breast cancer and had become progressively worse since. Following her surgery she was reluctant to mobilise due to her unsteady gait. She developed postural hypotension and depression but did not report any pain, paraesthesia or numbness. On examination, ataxia, reduced reflexes and reduced muscle tone with proximal muscle weakness were found. Eye examination revealed nystagmus to the left. A CT of the brain was normal. An MRI of the brain revealed bilateral white matter changes with large irregular lesions in the corona on both sides. The areas of change were lateral to and above the posterior aspects of the lateral ventricles, which were felt to be compatible with a lacunar-type infarct, but not diagnostic of the condition. Isotope bone scan confirmed degenerative bone disease in the same areas. There was no evidence of malignant cells on CSF analysis; however, oligoclonal bands were present and total protein was raised. Serum and CSF anti-neuronal antibodies (anti-Yo, anti-Hu) were also negative as well. Serum antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and anti-Sjogren syndrome antibodies (anti-SSA) were positive, but no rheumatological disease was found.

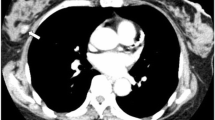

Nerve conduction studies showed a nearly 100% increase in compound motor action potential area following maximal voluntary activation for 15 s from 5.7 to 10 mV s from right ulnar ramus profunda nerve (Fig. 1). These findings were consistent with LEMS. Serum anti-VGCC (voltage-gated calcium channels) antibodies were also elevated (382 PM; normal range 0–45) confirming LEMS. SCLC was ruled out by CT of thorax and bronchoscopy with broncho-alveolar lavage cytology.

The patient was commenced on dexamethasone, but this resulted in a slight improvement only. However, six cycles of CMF chemotherapy, which were started 5 weeks after her diagnosis, significantly improved her unsteady gait. Hormonal manipulation was initiated with anastrozole, subsequently she also received adjuvant radiotherapy to her conserved breast. Five months later, due to a relapse of her neurological symptoms, a second course of CMF chemotherapy was commenced. Nine months after her initial diagnosis, the only remaining symptoms were sciatic-like pain radiating down to the back of her left thigh and leg with associated numbness at the ankle. Serum anti-VGCC levels decreased, but still remained elevated (105 PM), anti-Yo and anti-Hu anti-neuronal antibodies were negative at this time. One and a half years after her initial diagnosis of breast cancer the patient could resume full-time work as her symptoms of fatigue had significantly improved. She has remained free of local or distal recurrence in the last 5.5 years.

Discussion

Paraneoplastic LEMS is characterised by the production of IgG antibodies against presynaptic P/Q-type voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) expressed by the primary tumour [1]. These auto-antibodies decrease calcium entry into the presynaptic terminal of the neuromuscular junction, hence decreasing acetylcholine vesicle binding to the membrane and its consequent release [5]. The incidence of paraneoplastic LEMS in breast cancer is not known, since only a few cases have been reported in the literature.

Symptoms of LEMS have an insidious onset and may antedate the diagnosis of cancer. Typically, patients with LEMS present with proximal muscle weakness in the lower limbs. In addition, autonomic disturbances may be present, characterised by dry mouth or postural hypotension. Examination may reveal that strength is not as poor as is reported by the patient and initially improves with exercise. Tendon reflexes may be reduced or absent, but may be elicited by repeated tapping of the muscle tendon. Sensation is not affected.

Electrophysiological testing is diagnostic. Small compound action potentials and then dramatically increased facilitation observed with exercise or with repetitive nerve stimulation are pathognomic for LEMS [6]. A serum test for anti-VGCCs antibodies confirms the diagnosis [6]. Successful treatment of the underlying cancer leads to improvement of symptoms of LEMS in many patients.

Patients with subacute cerebellar degeneration usually present with ataxia, wide-based gait, intention tremor, nystagmus, vertigo, but cognition is spared [3]. PSCD is associated mainly with lung, breast, ovarian, renal, gastrointestinal, thyroid, laryngeal, and prostatic cancer [3]. However, the exact pathophysiological mechanism of PSCD is not known; it is proposed that anti-Purkinje cell IgG antibodies destroy the cerebellar Purkinje cells. Cerebellar cortical damage can be diagnosed by histology only, since imaging modalities are unhelpful. Clinical diagnosis of PSCD is confined to the presenting symptoms and a positive anti-Purkinje cell antibody assay [3, 4].

Concomitant LEMS and PSCD is a very rare entity. Similar to our case, patients usually present with symptoms characteristic to both diseases [3]. While the presence of one PND does not necessarily predispose the patient to another one, it has been suggested that the coexistence of PSCD and LEMS might be relatively frequent [4]. In a study of SCLC patients diagnosed with PSCD, 16% were found with concomitant LEMS. Furthermore, 24% of the patients had increased VGCC antibody levels. However, most of the patients did not have electrophysiological testing performed; therefore this association may even be underrepresented [4].

Interestingly, a different response to chemotherapy has been described in SCLC patients having concomitant PSCD and LEMS as compared to PSCD alone. SCLC patients having both PNDs respond better to chemotherapy in terms of improvement in paraneoplastic neurological symptoms [4]. In our breast cancer patient, the symptoms of PND responded well to repeated chemotherapy, which supports the previous findings in patients with SCLC.

In conclusion, in a patient diagnosed with atypical LEMS, when there is no evidence of respiratory malignancy, breast cancer should be included in the differential diagnosis.

References

Sanders DB (2003) Lambert–Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome: diagnosis and treatment. Ann N Y Acad Sci 998:500–508

Gatti G, Simsek S, Kurne A et al (2003) Paraneoplastic neurological disorders in breast cancer. Breast 12:203–207

Leonovicz BM, Gordon EA, Wass CT (2001) Paraneoplastic syndromes associated with lung cancer: a unique case of concomitant subacute cerebellar degeneration and Lambert–Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome. Anesth Analg 93:1557–1559

Mason WP, Graus F, Lang B et al (1997) Small-cell lung cancer, paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration and the Lambert–Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome. Brain 120:1279–1300

Wirtz PW, Lang B, Graus F et al (2005) P/Q-type calcium channel antibodies, Lambert–Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome and survival in small cell lung cancer. J Neuroimmunol 164:161–165

Oh SJ, Kurokawa K, Claussen GC, Ryan HF Jr (2005) Electrophysiological diagnostic criteria of Lambert–Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome. Muscle Nerve 32:515–520

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Romics, L., McNamara, B., Cronin, P.A. et al. Unusual paraneoplastic syndromes of breast carcinoma: a combination of cerebellar degeneration and Lambert–Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome. Ir J Med Sci 180, 569–571 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-008-0257-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-008-0257-5