Abstract

Background

Medication discrepancies at the time of hospital discharge are common and can result in error, patient/carer inconvenience or patient harm. Providing accurate medication information to the next care provider is necessary to prevent adverse events.

Aims

To investigate the quality and consistency of medication details generated for such transfer from an Irish teaching hospital.

Methods

This was an observational study of 139 cardiology patients admitted over a 3 month period during which a pharmacist prospectively recorded details of medication inconsistencies.

Results

A discrepancy in medication documentation at discharge occurred in 10.8% of medication orders, affecting 65.5% of patients. While patient harm was assessed, it was only felt necessary to contact three (2%) patients. The most common inconsistency was drug omission (20.9%).

Conclusions

Inaccuracy of medication information at hospital discharge is common and compromises quality of care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adverse events experienced by patients at discharge from hospital are commonly related to medication use [1–4]. Approximately one third of adverse drug events occurring around the discharge period are the result of error [3]. Effective and accurate prescription information should be transferred from the hospital to the patient’s GP and community pharmacist to ensure optimal patient care [2, 4].

The inaccuracy of medication documentation at discharge has been demonstrated in other jurisdictions [5–7]. Policy documents outlining strategies to promote medication safety for patients moving from one care environment to another have been produced in the United Kingdom (UK) [8] and the United States (US) [9]. At present, there exists no such policy or recommendations in the Irish setting, nor is there any published evidence to suggest the need. This study investigated the quality and consistency of medication documentation produced for transfer to the next care provider at patient discharge.

Participants and methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in a 600 bed academic teaching hospital in Ireland. Written consent for participation in the study was obtained, and the study was granted Hospital Ethics Committee approval.

The current prescribing process involves a junior doctor hand writing inpatient medication orders onto a drug prescription form. At discharge, the doctor writes the discharge prescription and transcribes medication details onto a discharge summary sheet.

The study took place over a 3 month period from 17 January to 17 April 2006. Included were all patients admitted to and discharged from inpatient cardiology care in four chosen medical wards. Excluded were patients who were transferred from the hospital to another care facility for further surgical intervention.

Measures and data collection

The assessment was conducted at discharge. All documents listing medication were reviewed and assessed for accuracy and congruency of details. This included:

-

inpatient drug prescription form

-

discharge summary sheet

-

discharge prescription

-

case notes.

Any anomalies were analysed for their potential to cause patient harm using a validated visual analogue scale between 1 (no harm) and 10 (death) [10]. A panel of five experienced healthcare professionals (a drug safety co-ordinator, two clinical pharmacists, a cardiology registrar and a cardiology clinical nurse manager) independently scored the clinical importance of every error. The mean score for each error was calculated and categorised as potential to cause none or minor (mean score <3), moderate (mean score 3–7), or severe (mean score >7) patient harm.

Definitions

Where medication details documented for any given patient were not harmonised across the case notes, drug prescription form, discharge summary sheet and the discharge prescription, it was recorded as an inconsistency. For the purpose of the study a prescribing error was defined as a prescribing decision or prescription writing process that results in an unintentional, significant reduction in the probability of treatment being timely and effective or increase in the risk of harm, when compared with generally accepted practice [11].

Omission of medication prescribed on an as required basis during inpatient stay was not recorded as an inconsistency, for example discontinuation of deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis once patient became mobile upon discharge, discontinuation of sleeping tablets or laxatives prescribed on an as required basis during patient stay.

Ethical considerations

Throughout the study, where potentially serious adverse patient outcomes were uncovered, steps were taken by the research pharmacist and a cardiology consultant to take remedial action.

Data analysis

Data was entered onto and analysed using Microsoft Excel® and EpiCalc 2000®.

Results

A total of 192 patients admitted to inpatient care under the cardiology consultants were eligible for inclusion in the study. Of these 139 patients (72%) consented to participation (28 patients were admitted and discharged within such a short timeframe as to prohibit the opportunity to recruit them to the study; 25 patients refused to take part). Patient age ranged from 18 to 89 years (median 63). The median number of regular medications prescribed per patient upon discharge from hospital was 7 (range 1–19). A total of 70.5% of patients were male, 56.8% were medical card holders and 85% were discharged on a weekday. The median length of stay was 6 days (range 1–46).

Identification and classification of inconsistencies

Of the 139 patients recruited, inconsistency in documentation of discharge medications was observed in 91 (65.5%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 57 to 73%).

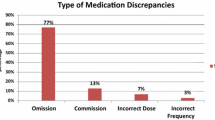

Any patient may have suffered more than one inconsistency and these may have been present in one or more of the documents (Table 1). Drug omission was the commonest inconsistency type observed.

Clinical importance of inconsistencies

A sum of 113 errors were identified in 1,046 medication orders (10.8%, 95% CI 9-12%). Errors were judged to have the potential to cause none or minor (47%), or moderate (53%) patient harm. None were judged to have the potential to cause severe patient harm. Examples of minor and moderate errors are provided (Table 2). Remedial action was taken for three (2%) patients to mitigate patient harm.

Inconsistencies related to day of discharge

When analysed according to day of discharge, there was no discernible difference in inconsistency rate between those discharged on a Saturday or Sunday and those discharged on a weekday (p = 0.11, χ2 = 2.56, DF = 1; relative risk 1.28).

Inconsistencies related to number of medications prescribed

When analysed according to increasing number of medications prescribed, the incidence of inconsistencies is significantly different between groups (p = 0.0004, χ2 = 16.17, DF = 2) (Table 3).

Discussion

Findings in this study add an Irish context to the evidence demonstrating inefficiencies and risk for patients moving between care environments [1, 2, 12, 13]. The number of patients who experienced a discrepancy is higher than reported elsewhere (range 11–53% of patients) [1–4]. The error rate per medication order is consistent with findings from UK but differs in that in the UK errors were detected in the routine course of clinical pharmacy service, providing an opportunity to take corrective action: Franklin et al. [14] reported an error rate of 9.2% across newly written, as required and discharge prescriptions; Tully and McElduff [15] reported an error rate of 10.7% identified by clinical pharmacists across all stages of patient stay from admission to discharge. Interestingly the current study found that patients discharged at the weekend, with on-call staff and limited support services, did not experience a greater risk of discrepancy than those discharged on a weekday. This illustrates the complexity of the process that involves the same level of input independent of day or level of support.

The authors acknowledge the limitations of this study, performed in a single service in one hospital involving a small number of patients. However the finding that almost two thirds of patients experienced an inconsistency, many of which had the potential to result in moderate patient harm, merits further investigation. It is worth noting that the discharge prescription is the only legal document on foot of which medication is dispensed, and discrepancies identified on the discharge summary may carry less potential for patient harm. Indeed this is borne out by the fact that the authors felt the need to contact only three patients to take corrective action. However, conscious of the importance of addressing systemic problems that underlie human errors, the authors seek to adopt a generative organisational safety culture [16] and focus on the discharge prescribing process, and improvements that can be made to it [17]. The prescribing process described is typical of that used in other specialty areas, and other hospitals in Ireland, and so similar findings would be expected elsewhere. The survey is currently being repeated in general medical and surgical services in the study hospital. Such investigation is a constructive and beneficial tool only when it leads to systematic improvements in patient outcomes. There are a number of evidence based strategies to improve standards of care at admission and discharge. The question is whether these strategies are adaptable to and feasible in the Irish setting.

The current discharge prescribing process involves reconciling four different medication lists, resulting in a high transcription burden, which is known to increase the risk of prescribing error [18]. It is perhaps not surprising therefore that drug omission was the commonest error type identified. This study demonstrates that the handwritten discharge summary is an unreliable source of medication information and in its current format a non-value added step in the process. This finding is supported by a recent systematic review which demonstrated that discharge summaries lack information on discharge medication in 2–40% of cases [7]. Electronic prescribing has been shown to decrease prescribing errors and increase prescribing quality in the US [19, 20] and the UK [21]. A pilot study in our hospital of electronic generation of the discharge prescription and summary using a surgical patient management system has demonstrated a significant reduction in prescribing errors. Results of this study will be reported elsewhere. The system is being adapted for use in a medical setting and will be piloted in cardiology later this year.

Intensive clinical pharmacy input from admission to discharge has been shown to improve patient outcomes in the UK [4, 14, 15], US [22] and Northern Ireland [23, 24]. Such services are the norm in the UK since the early 1990s [25, 26], but not in the Republic of Ireland. In the study hospital clinical pharmacy services are provided on admission and during patient stay but not at discharge. Resource constraints and a ceiling on the number of staff employed in each hospital represent barriers to service expansion [27]. Local research is warranted to investigate the feasibility and impact of extending clinical pharmacy services to the point of discharge.

The data presented in this study demonstrates the inefficiencies and medication safety risks inherent in the current discharge prescribing process. The authors hope to highlight the existence of this problem, assess the impact in other services and hospitals and demonstrate the need to design a new, sustainable and evidence based process which will improve patient outcomes in the Republic of Ireland, consistent with the Health Services Executive’s strategy for transformation [28].

Conclusions

Quality and accuracy of medication information imparted at discharge is poor and carries with it the potential to cause minor to moderate patient harm. This is largely attributable to the complexity of the process. Strategies for improvement include involvement of clinical pharmacists at the point of discharge and simplification of the process through the use of an electronic solution.

References

Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW (2003) The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Int Med 138(3):161–167

Forster AJ, Clark HD, Menard A, Dupuis N, Chernish R, Chandok N et al (2004) Adverse events among medical patients after discharge from hospital. CMAJ 170(3):345–349

Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW (2005) Adverse drug events occurring following hospital discharge. J Gen Inter Med 20(4):317–323

Duggan C, Feldman R, Hough J, Bates I (1998) Reducing adverse prescribing discrepancies following hospital discharge. Int J Pharm Pract 6:77–82

Colemann A (2002) Discharge information needs to be improved to prevent prescribing errors. Pharm J 268:81–86

Gandhi T, Sittig D, Franklin M, Sussman A, Fairchild D, Bates D (2000) Communication breakdown in the outpatient referral process. J Gen Intern Med 15:626–631

Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW (2007) Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital based and primary care physicians. Implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA 297(8):831–841

Smith J (2004) Building a safer NHS for patients: improving medication safety: Department of Health (UK)

Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) 2006 National Patient Safety Goals, Goal 8 hospital version accurately and completely reconcile medications across the continuum of care http://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/NationalPatientSafetyGoals/06_npsg_cah.htm. Accessed 23 Nov 2006

Dean BS, Barber ND (1999) A validated, reliable method of scoring the severity of medication errors. AJHP 56:57–62

Dean B, Barber N, Schachter M (2000) What is a prescribing error? Qual Health Care 9:232–237

Sexton J, Brown A (1999) Problems with medicines following hospital discharge: not always the patient’s fault? J Soc Adm Pharm 16(3/4):199–207

Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ (2006) The care transitions intervention: results of a randomised controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 166(17):1822–1828

Franklin BD, O’Grady K, Paschalides C, Utley M, Gallivan S, Jacklin A, Barber N (2007) Providing feedback to hospital doctors about prescribing errors: a pilot study. Pharm World Sci 29(3):213–220

Tully MP, McElduff P (2005) Identification of prescribing errors at different stages of hospital admission. IJPP 13:R29 (abstract)

Reason J (1997) Managing the risks of organisational accidents. Ashgate, Vermont

Cohen MR (2007) Medication errors, 2nd edn. American Pharmacists Association, Washington

Dean B, Schachter M, Vincent C, Barber N (2002) Causes of prescribing errors in hospital inpatients: a prospective study. Lancet 359(9315):1373–1378

Bates DW, Leape LL, Cullen DJ, Laird N, Petersen LA, Teich JM, Burdick E, Hickey M, Kleefield S, Shea B, Vander Vliet M, Seger DL (1998) Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors. JAMA 280:1311–1316

Bates DW, Teich JM, Lee J, Seger D, Kuperman GJ, Ma’Luf N, Boyle D, Leape L (1999) the impact of computerized physician order entry on medication error prevention. JAMIA 6:313–321

Donyai P, O Grady K, Jacklin A, Barber N, Franklin BD (2007) The effects of electronic prescribing on the quality of prescribing. Br J Clin Pharm; Online early article (July), doi:10.1111/j.1365–2125.2007.02995.x

Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotungo MC, Wahlstrom SA, Brown BA, Tarvin E et al (2006) Role of pharmacist counselling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med 166(5):565–571

Beagon P, Scott M, McElnay J (2004) Quantifying the impact of an intensive clinical pharmacy service on readmission rates to hospital. Pharm World Sci 26:A9

Scullin C, Scott MG, Hogg A, McElnay JC (2007) An innovative approach to integrated medicines management. J Eval Clin Pract; online early release July 2007: doi: 10.1111/j.1365–2753.2006.00753.x

Sexton J, Ho YJ, Green CF, Caldwell NA (2000) Ensuring seamless care at hospital discharge: a national survey. J Clin Pharm Ther 25(5):385–393

Jackson C, Owe P, Lea R (1993) Pharmacy discharge—a professional necessity for the 1990s. Pharm J 250:502–506

Delaney T (2007) Hospital pharmacy staffing and workload in Irish acute hospitals. IPJ 85(4):136–144

Health Service Executive. Transformation programme 2007–2010. http://www.hse.ie/en/Publications/TransformationProgramme2007–2010/FiletoUpload,4309,en.pdf. Accessed 30 Aug 2007

Acknowledgments

Completion of this study would not have been possible without the help of nursing, pharmacy, medical and administrative staff in the study hospital. The authors also wish to acknowledge the time and input of those involved in assessing the clinical importance of medication errors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Grimes, T., Delaney, T., Duggan, C. et al. Survey of medication documentation at hospital discharge: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. Ir J Med Sci 177, 93–97 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-008-0142-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-008-0142-2