Abstract

There are many factors that determine what forestry activities forest owners carry out in their forest properties and that influence whether forest owners engage in entrepreneurial activity. This paper explores whether the values and objectives of forest owners influence their forestry behaviour and their engagement in entrepreneurial activity. This is done through a review of the literature on private forest owners’ typologies based on owners’ objectives. The review reveals that typologies typically divide forest owners into two main groups. The primary objective of the first group of owners is production (of wood and non-wood goods and services) usually, although not exclusively, so as to generate economic activity. The primary objective of the second group is consumption (of wood and non-wood goods and services). There is a tacit assumption in the studies reviewed that goals and objectives do influence forestry behaviour but few studies have actually assessed whether this is the case. The general finding is that forest owners whose objectives are timber production and who are business-oriented are more likely to manage and harvest their stands. No research focusing on the link between owners’ objective and wider entrepreneurial activity in forests was found.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Private forest management is primarily a voluntary action with few legal constraints. The exceptions include central and eastern European post-communist countries where forest management is strongly affected by various laws and regulations, and countries where receipt of financial assistance for afforestation requires compliance with regulations (as is the case in Ireland). In many countries, aside from the potential requirement to reforest after final felling, forest owners can largely decide which management activities they pursue in their forests.

The characteristics of the forest holding and the financial position of the owner play a role in this decision-making. However, forest owners’ attitudes towards forestry and their objectives concerning their forest property are perhaps the most important factors affecting management decisions. This is an underlying assumption in many empirical studies on forest management behaviour of non-industrial private forest (NIPF) owners. This assumption has often been implicit, rather than being explicitly based on direct analysis of factors motivating forest owners’ behaviour. Demographic characteristics, including income and occupation, are often used as proxies of owners’ attitudes or preferences. Even when attitudes or ‘reasons for owning forest land’ have been explicitly elicited, the analysis of their effects on actual behaviour has often been descriptive or non-existent.

One of the core objectives of EU rural development policy is to encourage the diversification of economic activity in rural areas in order to promote viable and sustainable rural communities (EC 2006). Diversification of economic activity will inevitably involve entrepreneurship. Rametsteiner et al. (2006) observed that entrepreneurship is a multifaceted, complex social and economic phenomenon, which has given rise to a range of definitions. However, they noted that it essentially refers to the process of change, and in a business context this means to start up a new business. While external factors, including government policies, influence whether there is a demand for entrepreneurship, the ability of a firm or an individual to engage in entrepreneurship is affected by their resources and capabilities as well as their attitudes (Niskanen et al. 2007).

Forest owners are a heterogeneous group (Kurtz and Irland 1987) and their objectives for their forest ownership can vary greatly. In the context of the aims of COST E30, it is important to explore whether there is evidence that ownership objectives influence forest owners’ engagement in entrepreneurial activity and start-ups.

A literature review was undertaken of studies concerning private forest owners’ objectives, to establish whether there is evidence that these objectives act as barriers to—or facilitate—entrepreneurship. Other relevant factors affecting start-ups such as policies, resources and capabilities, are beyond the scope of this review. Rametsteiner et al.’s (2006) description of entrepreneurship as a process of change, usually involving starting up something new, is used. Thus forest owners who undertake new activities in their forests are considered entrepreneurs. The paper focuses initially on forest owner typologies that have been developed based on forest owners’ objectives. Research that specifically links these typologies to the forestry behaviour of the owners and entrepreneurial activity is then reviewed in more detail.

Review of Forest Owner Typology Literature

The typologies identified in the literature review were obviously influenced by the objective of the research from which they were derived. In some cases the research objective has been stated explicitly. For example, the typologies outlined by Kline et al. (2000) were developed to identify forest owners’ willingness to accept incentive payments to forego harvesting in order to improve wildlife habitat. Yet despite the differing research objectives, many of the typologies developed are similar. Thus in the analysis that follows, common types of owners that emerged through the literature review are identified. Table 1 reports a selection of studies in which some or all of these types were identified.

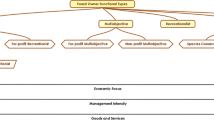

At basic level most typologies divide forest owners into two main groups depending on their objectives for their forests. The primary objective of one group is the production of wood and non-wood goods and services usually so as to generate economic activity, while the primary objective of the second group is consumption (of wood and non-wood goods and services). This latter group is often then further subdivided, as described in Table 1.

Forest Owners Whose Primary Objective is Production

Kurtz and Lewis (1981) developed a typology of forest owners in eastern USA based on their motivations and objectives. One of the four groups of owners they identified was the timber agriculturist who grows and harvests timber in a sustained manner. This group was portrayed as business-oriented and attempting to maximize the financial returns from timber. Similarly, Marty et al. (1988) identified one cluster of forest owners in Missouri as timber agriculturists. These were described as business-oriented owners who felt that trees could be managed similarly to agricultural crops to return a profit. Kline et al. (2000) also identified a group of American forest owners as timber producers who place priority on timber production and land investment considerations. In Lithuania, Mizaraite and Mizaras (2005) classified one group of forest owners they surveyed as businessmen whose objectives are to earn income from sales of wood and non-wood products.

Some typologies separate the timber production goal from the economic goal. For example, Lönnstedt (1997) identified a group of forest owners in Sweden with formal economic goals who aimed to attain a positive cash flow. The use of profits to fund investment in equipment, forest roads and property expansion were also considered important by this group. A separate group with informal economic goals was also identified. This latter group emphasised profit-making related to earnings from hunting and the provision of firewood. Lönnstedt (1997) distinguished both these groups with economic goals from a further group he identified as having production goals. The aim of forest owners with production goals was to increase the standing volume, cuttings and the level of increment in their woods. In a more recent study of Swedish forest owners, Hugosson and Ingemarson (2004) also differentiated between those with production motivations which comprised the production of wood and its harvesting for sale (as well as for domestic consumption) and those with economic efficiency goals. This latter group of forest owners had economic objectives for managing their forests. Karppinen (1998, 2000) described investors as forest owners who regarded their forest property as an asset and a source of economic security, providing financial security for old age. He also identified a group of owners classified as self-employed who valued regular sales income and labour income from delivery sales (in which the seller does the logging and hauling). The forest owners also stressed the importance of ‘household timber’. In their survey of German forest owners, Von Mutz et al. (2002) found a group they labelled economically oriented owners, who used their forests as a source of income for consumption and a source of economic security.

Some forest owner types could be equally assigned to the group with production goals or to those classed as having multiple objectives. For example, the classic forest owner described by Boon et al. (2004) placed greatest importance on forest income generation. However, they also valued the environmental and recreational aspects of forest ownership, and attached importance to the forest as a legacy.

Forest Owners Whose Primary Objective is Consumption

A number of forest owner types have been identified, the primary objective of which is consumption. These generally range from owners whose primary objective is the production of wood and non-wood products for their own use to those who have either multiple objectives or no explicit objectives for their woods.

Consumption of Wood and Non-wood Products

A number of typologies have identified a specific type of forest owner whose objective is the production of wood and other products for their own use. For example, Mizaraite and Mizaras (2005) identified the consumer group of forest owners in Lithuania whose main motivation for forest ownership is the extraction of wood and non-wood products for personal use, and for whom the collection of fuelwood is highly important. Wiersum et al. (2005) in their study of forest owners in Austria, Denmark, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, The Netherlands and Spain, found a type they described as self-interested forest owners who use the forest mostly for providing products for their own use.

Forest Owners with Non-timber Goals

A type of forest owner, described as a forest environmentalist, was identified by Kurtz and Lewis (1981). These are owners whose primary objective for their forest is the generation of non-timber outputs such as aesthetic values, wildlife and privacy. Marty et al. (1988) used a similar term to describe a group of forest owners in Missouri who are primarily concerned with the non-tangible benefits from their forest. These authors classed a further group of forest owners as forest recreationists, these being people who own forest land primarily for recreation and enjoyment. A similar group of forest owners was identified in Finland by Karppinen (1998, 2000). This group, also referred to as recreationists, emphasized the non-timber and amenity aspects of their forest ownership, including outdoor recreation, aesthetic considerations and berry-picking. Forest owners in the USA, who were classed as recreationists by Kline et al. (2000), were found to value the non-timber objectives of forest ownership, such as recreation and enjoyment of green space, and to some extent stressed bequest motives. In Lithuania, a forest owner type known as an ecologist, were found to value nature conservation highly (Mizaraite and Mizaras 2005). Hugosson and Ingemarson (2004) identified a group of Swedish forest owners with conservation objectives. These emphasized the protective function of forests. Biodiversity and forest landscape management are also key objectives of these owners. Also in Sweden, Lönnstedt (1997) described a type of forest owner with environmental goals, who particularly stressed the aesthetic aspects of their forests. Wiersum et al. (2005) also found a forest owner type they called environmentalists, who place priority on nature and landscape.

Another group of owners who can be categorized as having non-timber goals are those with amenity objectives. Hugosson and Ingemarson (2004) outlined how this group stressed the intangible aspects of forest ownership. Emotional ties to the forest estate and social contacts with relatives, friends, other forest owners, and foresters, can be of importance for this group. Similarly, Lönnstedt (1997) described Swedish forest owners (some of whom resided on the holding and some of whom were absentee owners) with intangible goals as those who wish for a particular lifestyle from the forest such as the opportunity (for the absentee owners) to meet neighbours during the hunting season. Boon et al. (2004) used the term hobby owners to describe those who attach importance to the forest as a place for hobby activities and who value the aesthetic and biodiversity aspects of forests. Forest owners who consider their forest mainly as a place for outdoor recreation or hunting or as an object of nature conservation were labelled leisure-oriented owners by von Mutz et al. (2002).

Forest Owners with Multiple Objectives

Many forest owners have been classified as multi-objective in typologies. In their overview of typologies, Boon et al. (2004) described the multi-objective owner as being motivated by financial considerations as well as recreational, environmental and other values related to forest ownership. Marty et al. (1988) found a similar group of forest owners in Wisconsin which they labelled as forest utilitarians. This group holds forest land for a variety of purposes with no dominating philosophy. They do not manage their forest for sustained timber production and instead use the forest resource to satisfy immediate needs such as fuelwood, grazing, recreation and residence. These authors classed as timber conservationists forest owners in Missouri who manage their forests for the sustained production of timber crops and who have a long-term stewardship perspective and a concern for wildlife. One of the types of forest owner that Karppinen (1998, 2000) identified in Finland was the multi-objective owner who valued equally both the short-term and long-term monetary benefits as well as the amenity benefits of their forests.

Kline et al. (2000) characterized the group of forest owners they identified as multi-objective as those who emphasise economic benefits, non-timber benefits and personal gratification equally. In their study of forest owners, Wiersum et al. (2005) described the multifunctional forest owner as owners who place equal priority to economy, nature and landscape. Multi-objective owners have also been identified in Lithuania (Mizaraite and Mizaras 2005).

Indifferent or Passive Forest Owners

The final group of forest owners is often referred to as passive owners or indifferent owners. Wiersum et al. (2005) found that among the forest owners they surveyed in eight European countries, the largest group could be classed as indifferent. These have a low level of motivation concerning all the forest functions. Passive owners is the term used by Kline et al. (2000) to describe forest owners whose primary benefit derives from the satisfaction of owning forest land.

How Objectives Influence Forest Owners’ Behaviour

Few of the studies undertaken on typologies specifically addressed the link between the objectives and values of forest owners and their actual forestry behaviour. Those that did focused on forestry behaviour in the context of forest management from a timber production point of view (Marty et al. 1988; Kuuluvainen et al. 1996; Karppinen 1998; Hänninen et al. 2001; Ovaskainen et al. 2006). There was little evidence of an examination of forestry behaviour relating to the production of non-wood products and services. Marty et al. (1988) did examine forest management behaviour of forest owners but limited their investigation to timber production activities. Thus timber stand improvement, reforestation (planting or seeding), completion of timber inventories and harvesting timber were the activities investigated in their study. They found that timber stand improvement was the management practice most frequently used by timber agriculturalists in Missouri and resource conservationists in Wisconsin. Reforestation activities were common in the forests of resource conservationists in Wisconsin. The completion of timber inventories was also most common among timber-oriented owners, i.e. timber agriculturalists and resource conservationists. Timber was harvested, most commonly, as expected, by timber-oriented owners in both regions, i.e. by timber agriculturalists and resource conservationists. Interestingly, forest environmentalists in Missouri did not seem to ignore timber harvesting completely.

A link was established between landowner objectives, owner and holding characteristics, and harvesting and silvicultural behaviour by Karppinen (1998). The forest owner groups based on their objectives were identified by owner and holding characteristics using logit-models. Karppinen (1998) also analysed silvicultural and harvesting behaviour in these groups. Besides descriptive analyses, dummy variables indicating assignments to these groups were included along with other explanatory factors in an econometric timber supply function to investigate the effects of ownership objectives on timber sales (Kuuluvainen et al. 1996). The timber sales of NIPF owners were connected to their objectives: multi-objective owners harvested significantly more than the other three groups. Knowledge of forest owners’ assignment to the groups based on ownership objectives was similarly incorporated in the models when analysing forest owners’ reforestation behaviour. The results suggest that ownership objectives explain seeding, planting and seedling stand improvement activities (Hänninen et al. 2001). Forest owners categorised as investors were most active in seeding and planting and self-employed owners were most active in seedling stand improvement. Ovaskainen et al. (2006) studied factors affecting timber stand improvement. Notably, they found that the forest owners surveyed who emphasised amenity values were active in timber stand improvement. Jennings and van Putten (2006) explored the relationship between past logging activity of forest owners in Tasmania and their objectives of forest ownership. They found that greater proportions of those classed as income and investment owners, agriculturists and multi-objective owners than those classed as non-timber output owners indicated that they had harvested timber in the past 3 years. Non-timber output owners were the least likely to log in the future.

Entrepreneurial Activity and Forest Owners’ Objectives

In the analysis of the literature, little was found that directly relates to the entrepreneurial attitudes of private forest owners. Only Lunnan et al. (2006) considered this topic, although their study does not specifically link these attitudes to the values of owners and their objectives for their forests. Instead, their study of entrepreneurial attitudes and the probability of start-ups among private forest owners in southern Norway used entrepreneurship theory to determine why some farm forest owners choose to start up new activities, based on the forest resources they have. They carried out a postal survey in 2002 in which a questionnaire was sent to 500 owners of whom 45% responded. The sample was drawn at random from the membership list of a forest owners’ association in southern Norway. The owners were also asked whether they were considering offering new services and products to increase their income and whether they had undertaken a new start-up. It was found that 25% of those surveyed had experiences with new business activities (including commercialisation of hunting and fishing and renting out cabins). However, only one-third of these new business activities had a basis in forestry alone, while a further one-third had a basis in both forestry and farming. Logistic regression was used to determine which factors influenced whether a forest owner would start up a new business. Those variables shown to significantly influence this occurrence were whether the owner was a risk taker and whether they had actively searched for profitable business opportunities in the forestry sector.

Discussion

The review of the typology literature was designed to investigate whether there is evidence that the values and objectives of forest owners influence forestry behaviour from the point of view of entrepreneurship. What the literature reveals is that it is a tacit assumption of the studies that goals and objectives do influence behaviour, but few studies have actually assessed whether this is the case. The small number of studies that addressed this issue did not throw up any surprising results. As expected, with a few exceptions (e.g. Kuuluvainen et al. 1996), forest owners whose objective is timber production and who are business-oriented are more likely to manage and harvest their stands. These studies focussed on timber management and production behaviour and did not consider behaviour in the context of other activities in forests. Yet, as demand for these non-timber production activities (e.g. cut foliage production for the floristry market, nature-based tourism, non-wood products) increases, it is in these areas that entrepreneurial activity will be required.

In the absence of literature specifically addressing the relationship between forest owners’ objectives and entrepreneurial activity, the forest owner types are revisited and this relationship hypothesized. The assumption is made that income generation is one of the main drivers to entrepreneurial start-ups in forests and on farms.

Research has shown that the group of forest owners with production goals is most likely to engage in active forest management (e.g. Marty et al. 1998). Thus, entrepreneurial activity that relates to timber production might be most likely among this group. In that many of the owners that comprise this group are also motivated by economic concerns, the likelihood that they will engage in activities that can be shown to increase the financial returns from their forest enterprise is high. The types of activities could range from basic wood production activities (e.g. selling roundwood, involvement in logging and hauling) to setting up small-scale sawmills.

Although the group of forest owners with consumption goals mainly uses their forest products and services for domestic (on-farm) purposes, there may be potential also for entrepreneurial activities connected to forests. For instance, surplus fuelwood may be sold to neighbours and other customers. Similarly, berries and mushrooms could be sold on local markets.

The group of forests owners with the objective of amenity and recreation (for self and family) is unlikely to become involved in entrepreneurial activity. The basis for this judgment is that the economic return from the forest is not emphasised, so the typical motivation for entrepreneurial activity is absent. Conversely, it could be argued that the multi-objective group of owner is likely to become involved in entrepreneurial activity. Not only are financial motivations important to these forest owners but they also recognise and appreciate the variety of products and services that their forests supply. Thus they should be aware of the forest-related activities on which entrepreneurial activity can be based. There is evidence from the literature that this group harvests more that other groups (Kuuluvainen et al. 1996). Thus the holding of multiple objectives does not appear to hinder their involvement in timber production. This group may also become involved in entrepreneurial activity related to game management and hunting.

The group of forest owners classed as indifferent may offer possibilities for entrepreneurship. It seems unlikely given their lack of involvement in their forest that they might directly become involved in entrepreneurial activities but there may be an opportunity for others to make use of their forests for entrepreneurial activity. An example of this might be cut foliage production for which there is an increasing demand, perhaps through renting of fields. There are examples of this in Ireland where a cut foliage company leases the forest and undertakes all the management of the forest and the harvesting of the foliage while the owner benefits financially. These owners could also be interested in biodiversity protection if they received subsidies.

Concluding Comments

Private forest management behaviour is basically volitional. Knowledge of forest owners’ values, attitudes and ownership objectives is therefore of crucial importance in understanding and predicting forest owner behaviour in private woodlots. However, it is clear from the review that there is insufficient information on the link between forest owner objectives and forestry behaviour and entrepreneurial activity. While the relationships between owner objectives and entrepreneurial activity are hypothesised in this paper, these hypotheses need to be tested. A survey of forest owners would be required in this regard. Such a survey, if carried out on a Europe-wide basis, could also be used to establish the relative frequency of each type of forest owner on a Europe-wide basis. If this kind of information is available, policy-makers will be in a position to ensure that effective and efficient forest policy instruments are designed.

References

Boon TE, Meilby H, Thorsen BJ (2004) An empirically based typology of private forest owners in Denmark: improving communication between authorities and owners. Scand J For Res 19(Suppl. 4):45–55

EC, (2006) The EU rural development policy 2007–2013. http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/publi/fact/rurdev2007/en_2007.pdf (accessed 13/6/07)

Hänninen H, Karppinen H, Ovaskainen V, Ripatti P (2001) Metsänomistajan uudistamiskäyttäytyminen. [Forest owners’ reforestation behavior] Metsätieteen aikakauskirja 4/2001:615–629, Helsinki (In Finnish)

Hugosson M, Ingermarson F (2004) Objectives and motivations of small-scale forest owners; modelling and qualitative assessment. Silva Fenn 38(2):231–271

Jennings SM, van Putten IE (2006) Typology of non-industrial private forest owners in Tasmania. Small-scale For Econ Manag Policy 5(1):37–56

Karppinen H (1998) Values and objectives of non-industrial private forest owners in Finland. Silva Fenn 32(1):43–59

Karppinen H (2000) Forest values and the objectives of forest ownership (Doctoral Dissertation). Metsäntutkimuslaitoksen tiedonantoja [Finnish Forest Research Institute, Research Papers] Helsinki

Kline JD, Alig RJ, Johnson RL (2000) Fostering the production of non-timber services among forest owners with heterogeneous objectives. Forest Science 46(2):302–311

Kuuluvainen J, Karppinen H, Ovaskainen V (1996) Landowner objectives and non-industrial private timber supply. For Sci 42(3):300–309

Kurtz WB, Lewis BJ (1981) Decision-making framework for non-industrial private forest owners: an application in the Missouri Ozarks. J For 79(5):285–288

Kurtz WB, Irland LC (1987) Federal policy for educating private woodland owners: a suggested new focus. Natl Woodlands 10(3):8–44

Lönnstedt L (1997) Non-industrial private forest owners’ decision process: A qualitative study about goals, time perspective, opportunities and alternatives. Scand J For Res 12(3):302–310

Lunnan A, Nybakk E, Vennesland B (2006) Entrepreneurial attitudes and probability for start-ups—an investigation of Norwegian non-industrial private forest owners. For Policy Econ 8(7):683–690

Marty TD, Kurtz WB, Gramann JH (1988) PNIF owner attitudes in the Midwest: a case study in Missouri and Wisconsin. North J Appl For 5(3):194–197

Mizaraite D, Mizaras S (2005) The formation of small-scale forestry in countries with economy in transition: observations from Lithuania. Small-scale For Econ Manag Policy 4(4):437–450

Niskanen A, Slee B, Ollonqvist P, Pettenella D, Bouriard L, Rametsteiner E (2007) Entrepreneurship in the forest sector in Europe. Silva Carelica 52, University of Joensuu, Faculty of Forestry, Joensuu

Ovaskainen V, Hänninen H, Mikkola J, Lehtonen E (2006) Cost-sharing and private timber stand improvements: a two-step estimation approach. For Sci 52(1):44–54

Rametsteiner E, Hansen E, Niskanen A (2006) Introduction to the special issue on innovation and entrepreneurship in the forest sector. For Policy Econ 8(7):669–673

Von Mutz R, Borchers J, Becker G (2002) Forstliches engagement und forstliches engagmentpontenzial von privatwaldbsizern in nordrhein-westfalen—analyse auf der basis des mixed-rasch-models. Forstwissenschaftliches Centralblatt 121:35–48

Wiersum KF, Elands BHM, Hoogstra MA (2005) Small-scale forest ownership across Europe: characteristics and future potential. Small-scale For Econ Manag Policy 4(1):1–19

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of members of COST E30 Working Group 1 to the development of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ní Dhubháin, Á., Cobanova, R., Karppinen, H. et al. The Values and Objectives of Private Forest Owners and Their Influence on Forestry Behaviour: The Implications for Entrepreneurship. Small-scale Forestry 6, 347–357 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-007-9030-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11842-007-9030-2