Abstract

Purpose

To examine whether the implementation of Affordable Care Act (ACA) reduced the financial burden associated with cancer care among non-elderly cancer survivors.

Methods

Using data from the MEPS-Experiences with Cancer Survivorship Survey, we examined whether there was a difference in financial burden associated with cancer care between 2011 (pre-ACA) and 2016 (post-ACA). Two aspects of financial burden were considered: (1) self-reported financial burden, whether having financial difficulties associated with cancer care and (2) high-burden spending, whether total out-of-pocket (OOP) spending incurred in excess of 10% or 20% of family income. Generalized linear regression models were estimated to adjust the OOP expenditures (reported in 2016 US dollar).

Results

Our sample included adults aged 18–64 with a confirmed diagnosis of any cancer in 2011 (n = 655) and in 2016 (n = 490). There was no apparent difference in the prevalence of cancer survivors reporting any financial hardship or being with high-burden spending between 2011 and 2016. The mean OOP decreased by $268 (95% CI, − 384 to − 152) after the ACA. However, we found that the mean premium payments increased by $421 (95% CI, 149 to 692) in the same period.

Conclusions

The ACA was associated with reduced OOP for health services but increased premium contributions, resulting in no significant impact on perceived financial burden among non-elderly cancer survivors.

Implications for cancer survivors

The financial hardship of cancer survivorship points to the need for the development of provisions that help cancer patients reduce both perceived and materialized burden of cancer care under ongoing health reform.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer is the second leading cause of death and the costliest medical condition in the USA [1,2,3]. There were 15.5 million people with a history of cancer in 2016, and this number is expected to rise to over 18.1 million in 2020 [1,2]. Along with this increase in cancer prevalence, costs of cancer care are also projected to increase to approximately $173 billion in 2020, almost 40% increase from 2010 [2]. It is well documented that cancer survivors have higher out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditures [4,5] and face greater financial burden on their medical care [6,7,8,9]. Indeed, cancer survivorship has an adverse effect on the financial well-being of the patient as well as their families, depleting income and financial assets [8] and even increasing the risk of medical bankruptcy [10]. A greater share of medical expenses by survivors also often creates barriers to access to care [11] and limit their choices of treatment [12], resulting in poor health outcomes. As a result, dealing with this “financial toxicity” among cancer survivors has become a great concern in US health care [8].

It has been 8 years since the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was signed into law with the aim of expanding insurance coverage and improving access to care [13]. As one can infer from its name, one of the main goals of the ACA was to lessen the financial burden of health care, mostly by expanding health insurance coverage [13,14]. Extensive evidence has been documented that the provisions of ACA were successful in achieving its proposed goals, the national uninsured rate and OOP spending for health care decreased significantly [15,16,17]. However, current evidence concerning the impact of ACA is somewhat limited to the general population; little is known about its impact on the financial burden among cancer survivors. Considering the critical economic and clinical consequences of financial toxicity of cancer [8,10], it is essential to assess the impact of the ACA’s provisions on financial burden associated with cancer care. No known studies to date have examined cancer survivors’ perceived financial hardship and OOP expenditures after the ACA implementation.

Given the coverage expansion among cancer survivors [18], whether the ACA reduced burden of cancer care remains an important question. After the ACA implementation, the uninsured rate among cancer survivors decreased to 7.7% (a 38% decrease from 2012) [18]. Moreover, recent studies demonstrated that the provisions of ACA-reduced OOP spending for those with the low income [16,17] and chronic conditions [19]. Whether similar changes have occurred among cancer survivors is still unknown. Therefore, to fill this gap in the literature, we aimed to assess changes in self-reported financial burden associated with cancer care and total OOP expenditures between pre-and post-ACA periods. We also evaluated differences in those changes by insurance types among cancer survivors in the USA.

Methods

Data and analytic sample

We used data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) Household Component and Experiences with Cancer Survivorship Survey Supplement (ECSS) 2011 and 2016. MEPS-ECSS is nationally representative survey of cancer survivors, developed in collaboration with the National Cancer Institute, American Cancer Society, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality to improve the quality of data in MEPS for estimating the cancer survivorship burden in the USA. For sampled US households with at least one cancer survivor, the MEPS-ECSS collects information on both (subjective) perceptions of household financial burden associated with the diagnosed/treated cancer and (objective) measures of out-of-pocket spending on medical care and on health insurance premiums [20,21]. The survey was administered in 2011 and 2016 with an average response rate of 85.6%. We used the two waves of the MEPS-ECSS to examine aspects of financial burden in a pre-ACA year (2011) and a post-ACA year (2016).

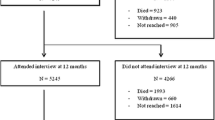

A total of 4407 US adults aged 18 or older with a confirmed diagnosis of any cancer and cancer treatment were eligible and completed the MEPS-ECSS in 2011 and 2016 (two distinct samples of family with cancer survivors). Given that the ACA coverage expansion targeted non-elderly population (those aged ≥ 65 are covered by Medicare) [13,14,22], we restricted our sample to individuals with cancer diagnosis between ages 18 and 64 years (n = 2036). Of those, we excluded those who only reported non-melanoma skin cancer (n = 5) because they are not classified as cancer survivors [23]. We also excluded those with non-positive survey weights (n = 876) because they are considered as missing in the survey-design adjusted analyses. These exclusion criteria resulted in our final analytic sample of 1155 cancer survivors aged 18–64 (n = 665 in 2011 and n = 490 in 2016).

Primary outcomes: self-reported financial hardship and high-burden spending

Our primary outcome of interest was whether there was a difference in financial burden associated with cancer care between 2011 (pre-ACA) and 2016 (post-ACA). We considered and used two aspects of financial burden: subjective (self-reported financial hardship) and objective (total out-of-pocket expenditure) measures. Subjective financial burden (self-reported, hereafter) was assessed using four questions related to the effect of cancer care on finance, following the previous approaches [6]. Respondents were asked if they ever (1) were unable to cover costs of medical care, (2) had to file for bankruptcy, (3) borrowed money or went into debt, or (4) worried about paying large medical bills because of cancer care. We defined cancer survivors with self-reported financial burden if they responded “Yes” to any of those four questions. The objective financial burden was assessed using the amount of total OOP expenditures (OOP for health services use plus premium payments) relative to annual family income. OOP spending on health services use was a summation of self-payment, deductibles, copayments, and other cost-sharing for ambulatory care, inpatient stay, prescription drugs or other types of care services [24]. Premium payments were self-reported amounts paid out-of-pocket for insurance coverage (for 2016 data, the amounts were adjusted to reflect the reduction achieved from premium subsidies under the ACA) [24]. Given shared financial resources and health insurance coverage within a family [25], we constructed family-level measure and defined cancer survivors with financial burden (high-burden spending, hereafter), if they incurred total OOP expenditure in excess of 10% or 20% of family income, respectively. These thresholds have been generally used for the indicator of high-burden spending on healthcare [17,25].

Cancer survivor characteristics

Cancer survivors’ sociodemographic variables included age groups (18–44, 45–54, 55–59, and 60–64 years), sex, race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and other), educational attainment (less than high school, high school degree or general equivalency diploma, some college, and college graduate or higher), marital status (married and unmarried), employment (employed and unemployed), family income level (federal poverty level [FPL] < 200% as low income, FPL 200–400% as middle income, and FPL > 400% high income), census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), health insurance coverage (private, public, and uninsured). Private insurance types were further defined for two groups (employment-based coverage [group] and individually purchased coverage [non-group]). Clinical characteristics included number of comorbidities (0, 1, and 2 or more), time since last cancer treatment (on treatment [current or < 1 year], 1–4 years, 5–9 years, ≥ 10 years, and never treated/unknown), and health scores (SF-12 Health Survey) [24]. Comorbidity conditions were assessed based on the MEPS priority condition that includes hypertension, high cholesterol, coronary heart diseases, angina, myocardial infarction, other heart diseases, stroke, emphysema, and diabetes [26]. Time since last cancer treatment was defined using two questions asking the person’s cancer diagnosis and treatment history, given the high correlation between treatment status and time since diagnosis [9].

Statistical analysis

Cancer survivors’ characteristics compared using the survey-design adjusted Wald F tests. We estimated annual OOP expenditures for each type of health services (ambulatory care, inpatient stay, prescription drugs, and other types of services) and premium payments using generalized linear regressions (GLM) with a gamma distribution and log link to account for skewness in the distribution of health expenditures. We imposed $1 floor of OOP to handle with zero expenditures (7.6% of the sample) in the GLM model [27]. All expenditures were inflated to 2016 dollar value using the consumer price index [28]. For the main analysis, linear regressions were modeled to estimate changes in the prevalence of the self-reported financial hardship and high-burden spending between pre-and post-ACA periods. All multivariable models were adjusted for differences in key characteristics that may affect health services utilization and expenditures, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, employment, census region, number of comorbidities, and time since cancer treatment, and the SF-12 health scores [9,27,29].

To further investigate the impact of ACA coverage expansion, the changes in the financial burden outcomes were compared for the four types of health insurance (group-based private, non-group private, any public, and uninsured) in subgroup analyses. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted to explore the changes in the main outcomes by age, race/ethnicity, family income level, and time since last treatment. Our analytic data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute) and accounted for the complex survey design to produce nationally representative estimates. This study used publicly available deidentified data and was deemed exempt by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board.

Results

Characteristics of non-elderly cancer survivors between 2011 (n = 655) and 2016 (n = 490) were comparatively similar (Table 1). Cancer survivors who reported self-reported financial burden tended to be younger, racial/ethnic minority, with low family income, or uninsured. Concerning high-burden spending, those with total OOP expenditure exceeding 20% of family income were likely to be female, married, with low family income, or insurance publicly funded. The full information on relationships of cancer survivor characteristics with the financial burden outcomes is available in Appendix Table 4.

Changes in self-reported financial hardship

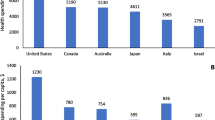

There was no apparent difference in unadjusted distribution of self-reported financial hardship between 2011 and 2016 (Fig. 1a; P = 0.831); specifically, no significant changes were observed for all financial hardship indicators: unable to cover the cost associated with cancer care (adjusted difference [AD] − 1.0%, 95% CI, − 4.7 to 2.9, P = 0.656), had to borrow money or go into debt (AD − 1.0%, 95% CI, − 4.4 to 2.3, P = 0.542), filed for bankruptcy (AD 0.0, 95% CI, − 1.3 to 1.4, P = 0.904); and worried about paying large medical bills (AD 1.6, 95% CI, − 3.9 to 7.2, P = 0.562; Table 2).

Distribution of self-reported financial hardship (a), high-burden spending (b), mean out-of-pocket spending by service types (c), and mean premiums payment (d) among cancer survivors between 2011 and 2016. Items of self-reported financial hardship include (1) unable to cover costs of medical care, (2) had to file for bankruptcy, (3) borrowed money or went into debt, and (4) worried about paying large medical bills because of cancer care. Estimates are weighted to be nationally representative using recommended stratification, clustering, and weighting by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Predicted values for expenditure were obtained from multivariable generalized linear model (gamma distribution and log link) adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, employment, family income level, insurance type, number of comorbidities, time since last cancer treatment, census region, and SF-12 physical and mental component summary scores

Changes in high-burden spending and OOP expenditures

The unadjusted proportions of cancer survivors having high-burden spending did not change significantly after the ACA (Fig. 1b; P = 0.644). However, the mean OOP decreased significantly by $268 (95% CI, − $384 to − $152) from $1513 in 2011 to $1245 in 2016 (Fig. 1c and Table 2). The reduction in OOP for inpatient stay and prescription drugs contributed most to this change (Fig. 1c). The mean premium payments increased by $420 (95% CI, $149 to $692) from $4500 in 2011 to $4920 in 2016. The adjusted prevalence of cancer survivors with total OOP exceeding 10% (AD − 1.6, 95% CI, − 7.4 to 4.2) or 20% (AD − 2.2, 95% CI, − 5.8 to 1.4) of their income also did not change significantly (P = 0.587 and 0.220, respectively; Table 2).

Subgroup analyses by health insurance type

The prevalence of self-reported financial hardship or having high-burden spending did not change for those with private insurance types (Table 3). For those with public insurance, the prevalence of having high-burden spending declined significantly (AD − 12.7%, 95% CI, − 22.4 to − 3.0). The amount of OOP for medical care decreased significantly for all insurance types in 2016, from − $128 for respondents with any public insurance to − $429 for uninsured respondents (P < 0.01 for all). However, concerning total OOP spending (OOP for medical care plus any premium contributions), there was significant reduction observed only for those with public insurance (AD − $886, 95% CI, − $1470 to − $302, P < 0.001). Among those with private insurance, the premium spending after the ACA was significantly increased for those with employer/group-based insurance type (AD $301, 95% CI, $57 to $467, P = 0.012), concerning total OOP spending (OOP for medical care plus any premium contributions),

Sensitivity analyses

Consistent with main findings, no significant changes in self-reported financial hardship were observed across these subgroups (P > 0.05 for all; Fig. 2a). However, we found that the prevalence of high-burden spending after the ACA was significantly decreased for those middle-aged, Hispanic, those with low-income, or who received last cancer treatment more than 10 years ago (Fig. 2b).

Prevalence of reporting any financial hardship (a) and high-burden spending (b) among cancer survivors between 2011 and 2016, by selected covariates. Estimates are weighted to be nationally representative using recommended stratification, clustering, and weighting by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. *Difference between 2011 and 2016 is statistically significant at P < 0.05

Discussion

This analysis of a national survey of cancer survivors demonstrated mixed effects of the implementation of ACA on the cancer survivor self-reported financial hardship. While there was no significant changes had been observed in the prevalence of self-reported subjective hardship, the study found statistically significant reduction on some self-reported objective hardship. In 2011 and 2016, one-third of non-elderly cancer survivors (2.7 million) reported having at least one indicator of financial hardship associated with cancer care, and nearly 11% of them (0.9 million), spent more than 20% of their family income on their medical care. For objective hardship, there was a statistically significant decline in OOP spending for health services between the study periods. However, the absolute amount of reduction may have been offset by the increased premium payments across insurance type. Subgroup analyses reveal that the most significant decline in objective financial burden occurred among those with public insurance. However, no significant decrease in self-reported subjective financial burden coincided, and they had the highest prevalence of reporting any of financial hardship. Taken together, our findings suggest that the ACA coverage expansion may not be associated with a reduction in the financial burden of health care among cancer survivors in the USA.

Several studies have reported that the ACA’s provisions reduced OOP spending for health care overall; [16,17,19] however, our study suggests the overall subjective financial burden is still not relieved. As reported in our study, 33.7% of cancer survivors still worried about paying their medical bill for cancer care, borrowed money to cover the cost, or filed bankruptcy in 2016, only 1% reduction from 34.7% in 2011. Cancer treatment is very expensive that may raise the cancer patients’ spending to the OOP maximum rapidly [8]. The average annual medical expenditure among those with cancer was more than twice than that of those with no history of cancer [23,30]. Families with cancer survivors may also have to reduce their monthly household expenses on necessities [31]. Consequently, the decreased OOP under the ACA may not be significant enough to be perceived among non-elderly cancer survivors as a whole. The adjusted reduction of total amount of OOP in our study ranged from $128 to $271 across the insurance type, considered a trivial amount compared with the actual average OOP spending of $1245 in 2016.

It is also plausible that the overall increase in premiums may outweigh the amount of OOP saved by less spending on health services among cancer survivors. We found that more than 77% of non-elderly cancer survivors had private insurance types, group-based or non-group/individually purchased, and incurred greater premium spending after the ACA ($447 more as combined; data not shown). Premiums continued to rise for those with group-based (e.g., employment); in 2016, the average employee contributions for family coverage were $5277, which was a 28% increase from $4129 in 2011 (compared with 11% increase in average workers’ earnings in the same period) [32]. For those with individually purchased plans, premiums may not be in a range where they could afford; even with ACA subsidies, those in coverage gap [33] or who newly gained marketplace plans depending on their income level may feel their contributions to premiums not affordable [34].

The decrease in mean OOP expenditures in this study appears to be driven by reduced spending for inpatient care and prescription drugs. Given that ACA was designed to promote primary care by providing various incentives through patient-centered care and value-based payment models [35,36], our findings may reflect a national shift of care delivery from inpatient to ambulatory care setting in the past several years [35]. It also seems plausible that, under these national efforts [35,36], patient-centered care has been encouraged in cancer care [37], promoting the patient-clinician discussion of financial toxicity of cancer care and meaningful use of high-value cancer drugs [8]. A large prescription data-based study also found that, although those who gained coverage under the ACA had an increase in the number of prescription fills, OOP spending on prescription drugs did not increase [19]. Consistent with previous studies on general population [17,38], our sensitivity analyses also suggest that racial/ethnic minorities or those with the low-income experienced a significant reduction in total OOP spending as intended under the ACA.

Several limitations should be noted in this study. First, the pre-and-post study design does not allow us to determine the causation between the ACA provisions and the change in financial hardship. However, our findings based on population-based data representing pre-and post-ACA periods likely reflect the impact of ACA implementation. Second, the recent economic recovery and growth may have influenced the study outcomes [39]. To address this, our study controlled for family income and employment status, two proxy of potential economic confounders. Although there were some differences in family income distribution between 2011 and 2016, it was likely to be national trends [39], and these differences in the income distribution were consistent when compared with the general population. Third, the data we used was from the year 2016, only 2 years after the ACA implementation; the study period may be too short to observe the full impact of ACA on financial hardship. Lastly, the self-reported financial hardship and health expenditures in the survey data are always subject to recall bias. Despite these limitations, the MEPS-ECSS is a widely used data source that can be representative of the population as having been diagnosed with or treated for cancer [20,21]. Use of two waves of the MEPS-ECSS provided us a unique opportunity to assess nationally representative change in financial hardship among cancer survivors in the USA.

Conclusions

Following the implementation of ACA, the financial burden associated with cancer care in non-elderly cancer survivor seems to be mixed in the USA. Although out-of-pocket spending for medical services decreased among cancer survivors with greater reduction in those with lower family income or racial/ethnic minority, the reduction on the self-reported financial hardship were yet to be observed among the cancer survivors. Future study with more matured data is needed to examine the effect of ACA on self-reported financial hardship. Our findings also suggest the need for the development of provisions that help cancer patients reduce both perceived and materialized burden of cancer care.

References

Miller KD, Siegel RL, Lin CC, Mariotto AB, Kramer JL, Rowland JH, et al. Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(4):271–89. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21349.

Mariotto AB, Robin Yabroff K, Shao Y, Feuer EJ, Brown ML. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(2):117–28. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djq495.

Akushevich I, Kravchenko J, Akushevich L, Ukraintseva S, Arbeev K, Yashin AI. Medical cost trajectories and onsets of cancer and noncancer diseases in US elderly population. Comput Math Methods Med. 2011;2011:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/857892.

Finkelstein EA, Tangka FK, Trogdon JG, Sabatino SA, Richardson LC. The personal financial burden of cancer for the working-aged population. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(11):801–6.

Guy GP, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, et al. Healthcare expenditure burden among non-elderly cancer survivors, 2008-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(6):S489–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.09.002.

Yabroff KR, Dowling EC, Guy GP, et al. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the United States: findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(3):259–67. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0468.

Zheng Z, Yabroff KR, Guy GP, et al. Annual medical expenditure and productivity loss among colorectal, female breast, and prostate cancer survivors in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(5):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djv382.

Carrera PM, Kantarjian HM, Blinder VS. The financial burden and distress of patients with cancer: understanding and stepping-up action on the financial toxicity of cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(2):153–65. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21443.

Yabroff KR, Lund J, Kepka D, Mariotto A. Economic burden of cancer in the United States: estimates, projections, and future research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2011;20(10):2006–14. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0650.

Ramsey S, Blough D, Kirchhoff A, Kreizenbeck K, Fedorenko C, Snell K, et al. Washington state cancer patients found to be at greater risk for bankruptcy than people without a cancer diagnosis. Health Aff. 2013;32(6):1143–52. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1263.

Shankaran V, Jolly S, Blough D, Ramsey SD. Risk factors for financial hardship in patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: a population-based exploratory analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(14):1608–14. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.37.9511.

Neumann PJ, Palmer JA, Nadler E, Fang C, Ubel P. Cancer therapy costs influence treatment: a National Survey of Oncologists. Health Aff. 2010;29(1):196–202. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0077.

Obama B. United States health care reform. JAMA. 2016;316(5):525–32. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.9797.

Hong YR, Holcomb D, Bhandari M, Larkin L. Affordable care act: comparison of healthcare indicators among different insurance beneficiaries with new coverage eligibility. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):114. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1362-1.

United States Census Bureau. Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2016.

Hong YR, Jo A, Mainous AG. Up-to-date on preventive care services under affordable care act: a trend analysis from MEPS 2007-2014. Med Care. 2017;55(8):771–80. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000763.

Goldman AL, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, Bor DH, McCormick D. Out-of-pocket spending and premium contributions after implementation of the affordable care act. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(3):347–55. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8060.

Davidoff AJ, Guy GP, Hu X, et al. Changes in health insurance coverage associated with the affordable care act among adults with and without a cancer history. Med Care. 2018;56(3):220–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000876.

Mulcahy AW, Eibner C, Finegold K. Gaining coverage through medicaid or private insurance increased prescription use and lowered out-of-pocket spending. Health Aff. 2016;35(9):1725–33. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0091.

National Cancer Institute. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS): experiences with cancer survivorship supplement. https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/meps/. Published 2018. Accessed October 3, 2018.

Yabroff KR, Dowling E, Rodriguez J, Ekwueme DU, Meissner H, Soni A, et al. The medical expenditure panel survey (MEPS) experiences with cancer survivorship supplement. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(4):407–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-012-0221-2.

Hamel MB, Blumenthal D, Abrams M, Nuzum R. The affordable care act at 5 years. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(25):2451–8. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMhpr1503614.

Guy GP, Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR, et al. Economic burden of cancer survivorship among adults in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(30):3749–57. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1241.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS HC-192: 2016 Full Year Consolidated Data File. https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h192/h192doc.shtml. Published 2018. Accessed September 28, 2018.

Banthin JS, Bernard DM. Changes in financial burdens for health care. JAMA. 2006;296(22):2712–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.22.2712.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS topic-priority condition. https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/MEPS_topics.jsp. Published 2009. Accessed October 15, 2018.

Deb P, Norton EC. Modeling health care expenditures and use. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39(1):489–505. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013517.

Bureau of Labor Statistics. Medical care in consumer price index. http://data.bls.gov/timeseries/CUUR0000SAM?output_view=pct_12mths. Published 2017. Accessed October 18, 2016.

Andersen RM, Davidson PL, Baumeister SE. Improving access to care. In: Changing the US Health Care System: key issues in health services policy and management, vol. 2013. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. p. 33–69.

Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR, Guy GP, et al. Medical costs and productivity losses of cancer survivors--United States, 2008-2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(23):505–10 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24918485.

Chino F, Peppercorn JM, Rushing C, Nicolla J, Kamal AH, Altomare I, et al. Going for broke: a longitudinal study of patient-reported financial sacrifice in cancer care. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14(9):e533–46. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.18.00112.

Claxton G, Rae M, Long M, Damico A, Whitmore H, Foster G. Health benefits in 2016: family premiums rose modestly, and offer rates remained stable. Health Aff. 2016;35(10):1908–17. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0951.

Garfield R, Damico A, Stephens J, Rouhani S. The coverage gap: uninsured poor adults in states that do not expand Medicaid - an update. Kaiser Fam Found. 2014;(October:1–8.

Blumberg L, Holahan J, Wengle E. Increases in 2016 marketplace nongroup premiums: there is no meaningful national average. The Urban Insitute. https://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2016/rwjf429398. Published 2016. Accessed October 1, 2018.

Schleicher SM, Wood NM, Lee S, Feeley TW. How the Affordable Care Act has affected cancer care in the United States: has value for cancer patients improved? Oncology (Williston Park). 2016;30(5):468–74 doi:217053.

Hong YR, Huo J, Mainous AG. Care coordination management in patient-centered medical home: analysis of the 2015 medical organizations survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(7):1004–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4439-1.

American Society of Clinical Oncology. American Society of Clinical Oncology position statement on addressing the affordability of cancer drugs. https://www.asco.org/sites/new-www.asco.org/files/content-files/blog-release/documents/2017-ASCO-Position-Statement-Affordability-Cancer-Drugs.pdf?et_cid=39454952&et_rid=1760459169&linkid=position+statement. Published 2017. Accessed November 1, 2018.

The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. The coverage gap: uninsured poor adults in states that do not expand Medicaid. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/the-coverage-gap-uninsured-poor-adults-in-states-that-do-not-expand-medicaid/. Published 2018. Accessed September 30, 2018.

Schoen C. The Affordable Care Act and the U.S. economy: a five-year perspective. The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2016/feb/affordable-care-act-and-us-economy. Published 2016. Accessed November 1, 2018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

• Study conception and design: Hong and Huo

• Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors

• Drafting of manuscript: Hong

• Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Smith, Mainous, and Huo

• Statistical analysis: Hong and Huo

• Administrative, technical, or material support: Hong and Xie

• Study supervision: Huo and Mainous

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they had no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This study was deemed exempt from review by the University of Florida Institutional Review Board because the use of publicly available dataset did not constitute human subjects research.

Informed consent

Since we used deidentified data, informed consent from the participants was not required.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, YR., Smith, G.L., Xie, Z. et al. Financial burden of cancer care under the Affordable Care Act: Analysis of MEPS-Experiences with Cancer Survivorship 2011 and 2016. J Cancer Surviv 13, 523–536 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00772-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00772-y