Abstract

Purpose

Cancer diagnosis in adults is often accompanied by negative impacts, which increase the risk of depression thereby lowering health-related quality of life (HRQoL). We examined the association between depression treatment and HRQoL among US adults with cancer and depression.

Methods

Patients age 18 and above, with self-reported cancer and depression diagnoses were identified from Medical Expenditure Panel Survey database for 2006–2013. Baseline depression treatment was categorized as antidepressants only, psychotherapy with or without antidepressant use, and no reported use of antidepressants or psychotherapy. HRQoL was measured using SF-12 physical component summary (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) scores. Adjusted ordinary least squares regressions estimated the association between type of depression treatment and HRQoL.

Results

Out of 450 (weighted per calendar year: 2.1 million) cancer adults included in the study, 51% received antidepressants only, while 16% received psychotherapy with or without antidepressants. In bivariate analyses, the mean MCS score was lowest among those who received psychotherapy with or without antidepressants compared to those receiving antidepressants only and those with no reported use of either modality, p < 0.05. In multivariate analyses, there was no significant difference in HRQoL by type of depression treatment.

Conclusion

Despite treatment for depression, HRQoL did not improve during the measurement timeframe. Quality of life is a priority health outcome in cancer treatment, yet our findings suggest that current clinical approaches to ameliorate depression in cancer patients appear to be suboptimal.

Implications for cancer survivors

Adults with cancer and comorbid depression should receive appropriate depression care in order to improve their HRQoL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cancer diagnosis in adults is frequently accompanied by negative impacts on mental health, changes in body image and function, persistent pain, distress and anxiety, and fear of cancer recurrence and death [1], due to which there is an increased risk of depression among adults with cancer [2]. In fact, 25% [1] to 38% [3,4,5] of adults with cancer have reported experiencing depression. Comorbid depression in adults with cancer is negatively associated with health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [6, 7], which, in turn, may decrease survival [8]. For instance, 16% of breast cancer survivors were reported to be depressed, and depression was inversely associated with HRQoL [9]. To improve HRQoL and hence survival in this vulnerable group, adults with cancer and comorbid depression should be offered pharmacological and/or psychological treatment for depression [10].

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) studying patients without cancer diagnoses have shown that depression treatment improves depression symptoms in a majority of patients [11,12,13]. Hence, it is highly likely that depression treatment, either pharmacological, psychological, or both, may improve HRQoL among adults with cancer and depression as well. To our surprise, there is a dearth of data from RCTs regarding the impact of depression treatment on HRQoL in patients with cancer. In fact, the authors of a systematic review on depression treatment in cancer patients identified only seven RCTs of pharmacological agents and four RCTs of non-pharmacological interventions [14]. Of the 11 studies included in the review, only three studies provided data describing quality of life measures [15,16,17]. Fisch et al. detected a significant improvement in quality of life with fluoxetine compared to placebo [15], while Razavi et al. identified no significant increase in quality of life scores with fluoxetine compared to placebo [16].

A more recent systematic review and meta-analysis [18] examining the use of antidepressants for treating depression in cancer patients reported that only three studies [15, 16, 19] included quality of life as an outcome. In addition to Fisch et al.’s study, Navari et al. also reported a statistically significant improvement in quality of life among fluoxetine users compared to those in the placebo group [19]. Yet, another systematic review of the effect of cognitive behavioral therapy for depression in adult cancer survivors reported improved quality of life with the therapy [20]. An RCT of collaborative care management of depression among cancer patients showed improvement in HRQoL, though the study may not be broadly generalizable as it focused on low-income, predominantly Hispanic patients [21].

Few studies which evaluated an impact of depression treatment on HRQoL have specifically focused on a particular type of cancer. For instance, studies in women with breast cancer reported that treatment of depression, either by pharmacological agents or psychosocial interventions, improves quality of life [22, 23] and longevity [22]. Furthermore, a majority of studies evaluated quality of life, which is a broad and distinctive construct measuring an overall general well-being, while HRQoL, which may evaluate physical, social, and mental health dimensions, specifically describes health construct using functioning and well-being [24].

Given that the evidence for the effectiveness of depression treatment on HRQoL in individuals with cancer is limited, of questionable quality, and not up-to-date, there is a pressing need for further research in this crucial area to inform treatment guidelines and clinical decision-making and to promote development and/or modifications of policies in cancer care. To our knowledge, there have been no nationally representative studies conducted which evaluated the impact of depression treatment on HRQoL among US adults with cancer. Hence, the primary objective of the study was to determine the prevalence of depression treatment among US adults with cancer diagnoses and comorbid depression, and examine the association between types of depression treatment and HRQoL measures in these patients in a multivariate framework. We hypothesized that among adults with cancer and depression, depression treatment would be associated with superior physical and mental HRQoL compared to those who did not report any depression treatment.

Methods

Study design and data source

A retrospective longitudinal study design with a baseline period of 1 year and follow-up period of 1 year was conducted using data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). Sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), MEPS provides nationally representative estimates of healthcare use, expenditures, source of payment, health insurance coverage, perceived physical and mental health status, HRQoL, and health insurance coverage from the US non-institutionalized civilian population [25]. Though MEPS is conducted annually, the survey follows individuals for two complete calendar years by interviewing them five times to minimize recall bias and to provide data for longitudinal studies [26, 27].

For the current study, the first year of observation was used as the baseline period and the second year was used as the follow-up period. In order to obtain adequate sample size, data from seven panels were combined: 11 (2006–2007), 12 (2007–2008), 13 (2008–2009), 14 (2009–2010), 15 (2010–2011), 16 (2011–2012), and 17 (2012–2013).

Study cohort

The MEPS collects detailed information about medical conditions that are defined as priority conditions by AHRQ [28], of which one is cancer. Adults aged 18 years and above with cancer were identified during the baseline year using clinical classification codes, 11–44 (except 23 for non-melanoma skin cancer) for cancer from the MEPS medical conditions files. The clinical classification codes are converted to International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes, from patient self-reported medical conditions including a report of diagnosis and conditions linked with medical events [29]. Adults with cancer who reported depression using clinical classification code of 657 and ICD-9-CM codes of 296, 300, and 311 were included in the study [30], while those who died during the survey year were excluded from the study as their HRQOL in the follow-up year would not be captured.

Measures

Dependent variable

Health-related quality of life

HRQoL was assessed during the follow-up year. As used in a previous study among cancer survivors [31], the summary scores obtained from the second version of the 12-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-12) were used to measure HRQoL. The SF-12 measures eight constructs: physical functioning, role limitations resulting from physical health problems, bodily pain, general health, vitality (energy/fatigue), social functioning, role limitation resulting from emotional problems, and mental health. The MEPS imputes HRQoL scores in the physical and mental health domains of HRQoL called the physical component summary (PCS) and the mental component summary (MCS) scores, respectively. The MEPS has rescaled the PCS and MCS scores with averages of 50 and standard deviations of 10 with respect to a proprietary US national dataset [32, 33].

Key independent variable

Depression treatment

Depression treatment was measured at baseline and grouped into three categories: (1) no report of depression treatment; (2) antidepressant use only; and (3) psychotherapy with or without antidepressants. As there were very few individuals with only psychotherapy, those who had psychotherapy with or without antidepressants were combined into one group. Antidepressants use was identified from the prescribed medications file using therapeutic class and subclass code of 249 (http://www.multum.com/Lexicon.htm). MEPS-prescribed medicine files contain information on therapeutic classes through linkage of Multum Lexicon database (http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st163/stat163.pdf). Psychotherapy visits were derived from the office-based visits and outpatient visits medical provider visits files. These files provide visit details including treatment and procedures obtained during the visit. Individuals with at least one visit for psychotherapy treatment were considered as receiving psychotherapy for depression [34].

Other independent variables

Demographic variables included age (18–39, 40–49, 50–64, 65+), gender (women, men), and race/ethnicity (White, African American, Hispanic, other) and marital status (married, widowed/separated/single). Socioeconomic characteristics were measured by education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college), poverty status (very poor, near poor, middle income, high income), area of residence (metro, non-metro), and US regions (Northeast, South, Midwest, West). Access to care was measured with health insurance coverage (private, public, uninsured), while health status was measured using number of chronic conditions (0, 1, 2+), baseline HRQoL scores, type of cancer (breast, lung, prostate/testis, cervical/female genital, colorectal/other gastrointestinal, melanoma, and other/non-specified), cancer remission status (yes, no), time since cancer diagnosis (< 2 years, 2–4 years, 5–9 years, ≥ 10 years). The co-occurring chronic conditions that were assessed consisted of asthma, arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, gastroesophageal reflux (GERD), heart disease, hypertension, osteoporosis, and stroke [31, 35].

Statistical analyses

Chi-square statistics were used to determine the significant differences between depression treatment categories and other independent variables. F tests were used to evaluate the unadjusted association between depression treatment categories and the HRQoL PCS and MCS scores. Ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions were conducted to evaluate adjusted associations between depression treatment categories and the HRQoL scores. Model 1 included depression treatment categories and all the other independent variables excluding baseline HRQoL scores, separately for PCS and MCS scores, while Model 2 included depression treatment categories and all the other independent variables including baseline HRQoL scores, separately for PCS and MCS scores. The findings that were significant with P values less than 0.05 levels are discussed. All analyses used the strata, cluster, and weights provided in the MEPS data to control for clustering and unequal probability design and were conducted in survey procedures using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.) to appropriately handle study weights and clustering.

Results

The study cohort included 450 adults with cancer diagnoses and comorbid depression who met the inclusion criteria. This represented 18% of the total US adults with cancer (data not shown). When weighted, this number approximated 2.1 million adults with cancer and comorbid depression for any calendar year within the study period. Table 1 reported the baseline characteristics of the study cohort and the significant differences in the characteristics by type of depression treatment. The majority of the study cohort was age 50 and older (74.8%), female (71.7%), white (74.0%), resided in metro areas (83.7%), had some college education (54.2%), had private health insurance (66.5%), had at least two comorbidities (59.1%), and had been cancer free for at least 10 years (53.3%).

Overall, 51.1% received antidepressants only, 16.2% received psychotherapy with or without antidepressants, and 32.7% reported no depression treatment. With regard to subgroup differences by types of depression treatment, adults age 40 and above with cancer and depression were more likely to receive antidepressants compared to their younger counterparts. While the youngest group in the cohort, those aged 18–39, were more likely to not receive any depression treatment. Married women (56.2%) and those with at least high school education (54.0%) were more likely to receive antidepressants compared to their respective counterparts. Adults living in a metro area received psychotherapy more frequently than those living in non-metro areas (18.4 vs. 4.4%). Geographically, the Northeast had the highest use of psychotherapy (27.3%) and lowest antidepressant use (38.2%), while the south had less use of psychotherapy (8.9%) and more frequent antidepressant use (57.5%).

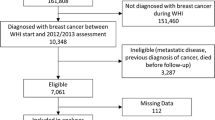

Figure 1 depicts rates of depression treatment among adults with cancer and comorbid depression by type of cancer. Our analysis showcased that psychotherapy was used less frequently across all cancer types, with the highest rate of use among those with other/non-specified cancers (21.3%) and the least use among those with melanoma (1.5%). Antidepressant use was more frequent than the use of psychotherapy or no treatment across all cancer types (range 46.8–81.1%), except for those with colorectal/other gastrointestinal cancer who were more likely to report no depression treatment (53.4%).

Table 2 highlights the weighted means and standard errors (SE) of HRQoL scores (PCS and MCS) during the baseline and follow-up years. During the baseline year, the mean PCS and MCS scores were 40.11 (SE = 0.58) and 43.13 (SE = 0.60), respectively. While during the follow-up year, the mean PCS and MCS scores were 40.32 (SE = 0.60) and 43.35 (SE = 0.57), respectively (Table 3). There were no significant differences in the baseline PCS and MCS scores by types of depression treatment. The result was consistent for the PCS scores in follow-up year with no significant differences in scores by types of depression treatment. However, the mean MCS score in the follow-up year was higher among those receiving antidepressants only compared with those who received psychotherapy with or without antidepressants (44.37 vs. 39.23, respectively; p = 0.0394). Appendix Tables 4 and 5 provide the weighted means and SE of PCS and MCS scores for each subgroup by types of depression treatment.

Table 3 reports the regression coefficient estimates (betas) and SE of types of depression treatment separately on PCS and MCS scores. In model 1, after controlling for all the independent variables except baseline HRQoL scores, adults with cancer and depression who reported psychotherapy with or without antidepressants had higher PCS scores in the follow-up period compared to those without any depression treatment; however, the results were not significant (data not shown). While adults who received antidepressants had nonsignificant lower PCS scores compared to those without any depression treatment (data not shown). In model 2, after controlling for baseline HRQoL in addition to other independent variables, the findings remained consistent with model 1.

With regard to the MCS scores, adults with cancer and depression who reported either antidepressant use or psychotherapy had nonsignificant lower scores compared to those who received no depression treatment in model 1. In model 2, after controlling for baseline HRQoL as well, the findings remained consistent with model 1 for psychotherapy, while those with antidepressant use had higher MCS scores compared to those who reported no depression treatment. Regardless of these differences, none of these estimates were statistically significant.

Discussion

Considering the high prevalence of depression and its negative impact on HRQoL and mortality among adults with cancer, it is highly concerning that only few trials have assessed the efficacy of depression treatment on HRQoL among this vulnerable group. To the authors’ knowledge, this study is first of its kind to evaluate the association between depression treatment and HRQoL among adults with cancer and depression in the real world using a nationally representative data. One third of the study cohort reported no use of depression treatment including antidepressants and/or psychotherapy, a finding significantly lower than that reported in the literature [36, 37]. Walker et al. reported that 73% of the cancer patients with depression did not receive any potentially effective depression treatment [36]. One could argue that limited evidence of the efficacy of depression treatment from the RCTs could be one of the causes of undertreatment of depression among adults with cancer. Moreover, use of other forms of strategies and interventions such as spirituality and spiritual coping, and participation in psychosocial support activities not captured by MEPS may be utilized by this group. Consistent with the literature [38, 39], there is an increased use of antidepressants (with or without psychotherapy) in the study cohort (total = 63%).

The established average baseline PCS and MCS norms for the nationally representative sample of adults with depression are 45.6 and 37.4, respectively [40]. While, for our study sample with cancer and comorbid depression, the PCS score is lower and the MCS score is higher than reported for adults with depression only. These findings indicate that cancer may lower physical functioning thereby affecting PCS component of the HRQoL. However, the average baseline PCS and MCS scores and hence HRQoL for adults with cancer and depression were lower compared to the norm for the adults with cancer (mean PCS 43.0; mean MCS 50.1) [31], indicating detrimental effect of depression on HRQoL and hence suggesting effective management of depression. In an unadjusted analysis, there were no significant differences in the PCS scores by type of depression treatment after 1 year follow-up. While those who reported antidepressant use only had significantly higher MCS scores, followed by those with no depression treatment and psychotherapy (with or without antidepressants) use. In the fully adjusted model, the significance disappeared demonstrating that depression treatment was not associated with an improvement in HRQoL scores during the study timeframe in this vulnerable group. These findings were contrasting to those reported in the previous studies which evaluated impact of depression treatment on quality of life among cancer patients [15, 19,20,21].

Although HRQoL is a priority health outcome in cancer treatment, the study findings exhibit that current depression management to ameliorate HRQoL among adults with cancer may be inadequate. A system of care which addresses all the shortcomings of current depression care is critically needed. For instance, highly efficacious complex interventions such as “Depression Care for People with Cancer” [41] comprising of education about depression and its treatment, problem-solving treatment to develop coping strategies, and communication about management of depression with each patient’s oncologist and primary care physician supplemental to usual source of care, could be developed and implemented to improve depression outcomes and HRQoL among adults with cancer and comorbid depression. Another efficacious intervention, collaborative telecare management supplemented with automated symptom monitoring, may also be implemented to improve HRQoL among this vulnerable group [42]. As there is modest evidence supporting pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions for depression among adults with cancer [14, 43, 44], a more definitive evidence from larger high-powered clinical trials is needed [45].

This study utilized a nationally representative survey data to evaluate the association between depression treatment and HRQoL among adults with cancer and depression and provided the national estimates. A comprehensive list of covariates was included to control for confounding bias when assessing the association. “No depression” treatment was used as a comparison group to examine the effectiveness of depression treatment in real-world settings. Though this study presents nationally representative estimates, there are limitations worth noting. Data is all self-reported and hence prone to recall bias. The study included adults with diagnosed depression, and hence, those with undiagnosed depression were not included. Also, duration and severity of depression which may impact HRQoL were not assessed and hence was not accounted for in the regression model. Moreover, though the study utilized longitudinal retrospective observational cohort design, causality could not be established. Though a comprehensive list of covariates was included to control for potential confounding bias, clinical information of cancer was not available and hence not controlled for in the study. However, time since cancer diagnosis and remission status were captured and included as covariates in the study.

Since the PCS and MCS scores derived from the SF-12 are deemed by few researchers to provide meager intuitive information, we calculated age-specific mean PCS and MCS scores [46] and evaluated the association between depression treatment and HRQoL. There were no significant differences in the strength and direction of the estimates (data not shown). Lack of information on initiation and duration of depression treatment may affect the estimates; however, we controlled for depression treatment use in the follow-up period which did not impact the direction and strength of the estimates (data not shown). With regard to psychotherapy, two groups, psychotherapy use with antidepressants and psychotherapy only, were combined due to a smaller sample size in psychotherapy-only group (3.8%), and hence, the difference in the association between these two groups was not assessed. Future research should investigate the separate impacts of psychotherapy with antidepressants and psychotherapy only on HRQoL among adults with cancer and depression to identify the effective modality.

Despite the above limitations, this study evaluated the association between depression treatment and HRQoL among adults with cancer and comorbid depression using nationally representative survey data. The study findings suggested that use of antidepressants or psychotherapy did not favorably impact HRQoL among this vulnerable group. Though quality of life is a priority health outcome in cancer treatment, the study implies current clinical approaches to ameliorate depression in cancer patients may be inadequate.

References

American Cancer Society. Anxiety, Fear, and Depression. Available at https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/physical-side-effects/changes-in-mood-or-thinking/anxiety-and-fear.html Accessed on June 15, 2017.

Chochinov HM. Depression in cancer patients. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:499–505.

Honda K, Goodwin RD. Cancer and mental disorders in a national community sample: findings from the national comorbidity survey. Psychother Psychosom. 2004;73:235–42.

Massie MJ. Prevalence of depression in patients with cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;32:57–71.

Pirl WF. Evidence report on the occurrence, assessment, and treatment of depression in cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2004;32:32–9.

Fann JR, Thomas-Rich AM, Katon WJ, Cowley D, Pepping M, McGregor BA, et al. Major depression after breast cancer: a review of epidemiology and treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30:112–26.

Faller H, Brahler E, Harter M, Keller M, Schulz H, Wegscheider K, et al. Performance status and depressive symptoms as predictors of quality of life in cancer patients. A structural equation modeling analysis. Psychooncology. 2015;24(11):1456–62.

Quinten C, Coens C, Mauer M, Comte S, Sprangers MA, Cleeland C, et al. EORTC Clinical Groups. Baseline quality of life as a prognostic indicator of survival: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from EORTC clinical trials. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:865–71.

Reyes-Gibby CC, Anderson KO, Morrow PK, Shete S, Hassan S. Depressive symptoms and health-related quality of life in breast caner survivors. J Women's Health. 2012;21(3):311–8.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Distress Management (Version 2.2016) 2016. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/distress.pdf Accessed June 15, 2017.

Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Nierenberg AA, Stewart JW, Warden D, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 Nov;163(11):1905–17.

Thase ME, Friedman SS, Biggs MM, Wisniewski SR, Trivedi MH, Luther JF, et al. Cognitive therapy versus medication in augmentation and switch strategies as second-step treatments: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2007 May;164(5):739–52.

Warden D, Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR. The STAR*D project results: a comprehensive review of findings. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9(6):449–59.

Rodin G, Lloyd N, Katz M, Green E, Mackay JA, Wong RKS, et al. The treatment of depression in cancer patients: a systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:123–36.

Fisch MJ, Loehrer PJ, Kristeller J, Passik S, Jung SH, Shen J, et al. Fluoxetine versus placebo in advanced cancer outpatients: a double-blinded trial of the Hoosier Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(10):1937–43.

Razavi D, Allilaire JF, Smith M, Salimpour A, Verra M, Descalux B, et al. The effect of fluoxetine on anxiety and depression symptoms in cancer patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;94(3):205–10.

Pezzella G, Moslinger-Gehmayr R, Contu A. Treatment of depression in patients with breast cancer: a comparison between paroxetine and amitriptyline. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2001;70(1):1–10.

Laoutidis ZG, Mathiak K. Antidepressants in the treatment of depression/depressive symptoms in cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-nalaysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:140–60.

Navari RM, Brenner MC, Wilson MN. Treatment of depressive symptoms in patients with early stage breast cancer undergoing adjuvant therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112:197–201.

Osborn RL, Demoncada AC, Feuerstein M. Psychosocial interventions for depression, anxiety and quality of life in cancer survivors: meta-analyses. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2006;36(1):13–34.

Ell K, Xie B, Quon B, Quinn DI, Dwight-Johnson M, Lee PJ. Randomized controlled trial of collaborative care management of depression among low-income patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(27):4488–96.

Somerset W, Stout SC, Miller AH, Musselman D. Breast cancer and depression. Oncology (Williston Park). 2004;18(8):1021–34.

Kissane DW, Grabsch B, Clarke DM, Smith GC, Love AW, Bloch S, et al. Supportive-expressive group therapy for women with metastatic breast cancer: survival and psychosocial outcome from a randomized controlled trial. Psychooncology. 2007;16(4):277–86.

Karimi M, Brazier J. Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: what is the difference? PharmacoEconomics. 2016;34:645–9.

Cohen JW, Monheit AC, Beauregard KM, Cohen SB, Lefkowitz DC, Potter DE, Sommers JP, Taylor AK, Arnett RH 3rd. The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey: a national health information resource. Inquiry. 1996–1997;33(4):373–389.

Smith M, Davis MA, Stano M, Whedon JM. Aging baby boomers and the rising cost of chronic back pain: secular trend analysis of longitudinal Medical Expenditures Panel Survey data for years 2000 to 2007. J Manip Physiol Ther. 2013;36(1):2–11.

Machlin SR, Chevan J, Yu W, Zodet MW. Determinants of utilization and expenditures for episodes of ambulatory physical therapy among adults. Phys Ther. 2011;91(7):1018–29.

AHRQ MEPS Topics: Priority conditions-General. Available at http://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/MEPS_topics.jsp?topicid = 41Z-1 Accessed June 15, 2017.

Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Clinical Classification Code to ICD-9-CM Code Crosswalk. http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h128/h128_icd9codes.shtml Accessed June 15, 2017.

Soni A Trends in use and expenditures for depression among US adults age 18 and older, civilian noninstitutionalized population, 1999 and 2009. Statistical brief # 377. July 2012 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Rockville, MD Available at https://wwwmepsahrqgov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st377/stat377pdf Accessed June 15, 2017.

Wang S, Hsu SH, Gross CP, Sanft T, Davidoff AJ, Ma X, et al. Association between time since cancer diagnosis and health-related quality of life: a population-level analysis. Value Health. 2016;19:631–8.

Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–33.

Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B. SF-12v2: how to score version 2 of the SF-12 health survey (with a supplement documenting version 1). Lincoln: QualityMetric Inc.

Harman JS, Edlund MJ, Fortney JC, Kallas H. The influence of comorbid chronic medical conditions on the adequacy of depression care for older Americans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(12):2178–83.

Pan X, Sambamoorthi U. Healthcare expenditures associated with depression in adults with cancer. J Community Support Oncol. 2015;13(7):240–7.

Walker J, Hansen CH, Martin P, Symeonides S, Ramessur R, Murray G, et al. Prevalence, associations, and adequacy of treatment of major depression in patients with cancer: a cross-sectional analysis of routinely collected clinical data. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(5):343–50.

Berard RMF, Boermeester F, Viljoen G. Depressive disorders in an outpatient oncology setting: prevalence, assessment and management. Psychooncology. 1998;7:112–20.

Grassi L, Nanni MG, Uchitomi Y, Riba M. Pharmacotherapy of depression in people with cancer. In: Kissane DW, Maj M, Sartorius N, editors. Depression and cancer. Chichester: Wiley; 2011. p. 151–76.

Ng CG, Boks MP, Zainal NZ, de Wit NJ. The prevalence and pharmacotherapy of depression in cancer patients. J Affect Disord. 2011;131:1–7.

Alenzi EO, Sambamoorthi U. Depression treatment and health-related quality of life among adults with diabetes and depression. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:1517–25.

Strong V, Waters R, Hibberd C, Murray G, Wall L, Walker J, et al. Management of depression for people with cancer (SMaRT oncology 1): a randomized trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9632):40–8.

Kroenke K, Theobald D, Wu J, Norton K, Morrison G, Carpenter J, et al. Effect of telecare management on pain and depression in patients with cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304(2):163–71.

Daniels J, Kissane DW. Psychosocial interventions for cancer patients. Curr Opin Oncol. 2008;20:367–71.

Jacobsen PB, Jim HS. Psychosocial interventions for anxiety and depression in adult cancer patients: achievements and challenges. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:214–30.

Williams S, Dale J. The effectiveness of treatment for depression/depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: A systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:372–90.

Utah Department of Health. Interpreting the SF-12. 2001 Utah Health Status Survey. Available at http://healthutahgov/opha/publications/2001hss/sf12/SF12_Interpretingpdf Accessed June 15, 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was not funded by any grant.

Conflict of interests

No conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

This study involved secondary databases analysis of a publicly available database, and hence, our institution deemed this study to be exempt from ethical approval.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vyas, A., Babcock, Z. & Kogut, S. Impact of depression treatment on health-related quality of life among adults with cancer and depression: a population-level analysis. J Cancer Surviv 11, 624–633 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0635-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0635-y