Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to describe patient perspectives on survivorship care 1 year after cancer diagnosis.

Methods

The study was conducted at an integrated healthcare delivery system in western Washington State. Participants were patients with breast, colorectal, and lung cancer who had enrolled in a randomized control trial (RCT) of oncology nurse navigation to improve early cancer care. Those alive and enrolled in the healthcare system 1 year after diagnosis were eligible for this analysis. Participants completed surveys by phone. Questions focused on receipt of treatment summaries and care plans; discussions with different providers; patient opinions on who does and should provide their care; and patient perspectives primary care providers’ (PCP) knowledge and skills related to caring for cancer survivors

Results

Of the 251 participants in the RCT, 230 (91.6 %) responded to the 12-month phone survey and were included in this analysis; most (n = 183, 79.6 %) had breast cancer. The majority (84.8 %) considered their cancer specialist (e.g., medical, radiation, surgical or gynecological oncologist) to be their main provider for cancer follow-up and most (69.4 %) had discussed follow-up care with that provider. Approximately half of patients were uncertain how well their PCP communicated with the oncologist and how knowledgeable s/he was in caring for cancer survivors.

Conclusions

One year after diagnosis, cancer survivors continue to view cancer specialists as their main providers and are uncertain about their PCP’s skills and knowledge in managing their care. Our findings present an opportunity to help patients understand what their PCPs can and cannot provide in the way of cancer follow-up care.

Implications for cancer survivors

Additional research on care coordination and delivery is necessary to help cancer survivors manage their care between primary care and specialty providers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Institute of Medicine’s 2007 report Lost in Transition [1] has significantly shaped cancer survivorship research and practice, but many research questions and implementation challenges remain [2–7]. There has been little comparative effectiveness research on different models of cancer survivorship care, and the optimal roles for different providers (e.g., primary care, oncology, gastroenterology, general surgery, etc.) in delivering ongoing care to cancer survivors remain uncertain. However, research suggests that patients who see both oncologists and primary care providers (PCPs) are more likely to receive evidence-based care specified by guidelines for follow-up, cancer screening, and general prevention [8–10]. Given these data and the shortage of oncologists relative to the growing number of cancer survivors, studies on the role of PCPs in cancer survivorship care are increasingly important.

One of the main models suggested for cancer survivorship care is shared care, which occurs when patient care is “shared by two or more clinicians of different specialties (or systems that are separated by some boundaries)” [11]. Previous research suggests shared care between primary care and oncology is the prevailing model in integrated healthcare delivery systems [12]. Healthcare leaders within integrated delivery systems favor shared care arrangements, but report that transitions between oncology and primary care are often informal [12]. A survey of a nationally representative sample of PCPs showed that nearly one third of these providers co-managed care for breast and colon cancer survivors and another 11 % reported being the main providers for both kinds of cancer survivors [13]. However, only 40 % of PCPs and 17 % of oncologists preferred a shared care model, while 26 % of PCPs and 59 % of oncologists, respectively, preferred oncologist-led care [14].

The goal of the present study was to describe patient experiences and perspectives on the coordination between and the role of different providers 1 year after cancer diagnosis. We included questions about survivorship follow-up care plans and treatment summaries, as these were recommended in the IOM report [1] and have received considerable attention in the literature and from professional societies and organizations. Ultimately, results from this study will inform development of delivery interventions and practice changes to assist cancer survivors during follow-up care.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted at Group Health, an integrated healthcare insurance and delivery system in the Pacific Northwest with a focus on primary care and the patient-centered medical home [15]. Group Health is part of the Cancer Research Network [16] and has previously participated in research on the organization of care for cancer survivors [12]. The population for this study consisted of Group Health enrollees with breast, lung, or colorectal cancer who were enrolled in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a nurse navigator intervention to improve support, communication and coordination of care around the time of diagnosis and through treatment. The control group received enhanced usual care. The 4-month intervention is described in detail elsewhere [17, 18]. The present analysis includes all clinical trial participants who remained enrolled at Group Health and responded to a 12-month follow-up questionnaire.

Data collection

Participants in this study were surveyed at three time-points: a baseline assessment shortly after diagnosis, a 4 months assessment near the end of the intervention period, and a 12-month assessment to capture longer-term outcomes. Outcomes of interest in this paper were collected 12-months after cancer diagnosis. We called RCT participants who were still alive and enrolled at Group Health to administer a 107-question follow-up survey by phone. We made up to 12 separate attempts to reach participants by phone and left up to three messages. We administered previously used questions related to cancer survivorship from: the Primary Care Delivery of Survivorship Care Scale [19]; the National Cancer Institute’s FOCUS study [20]; and studies by Cheung, Earle, and colleagues [21, 22]. Specifically, we asked about: receipt of treatment summaries and care plans; discussions patients had with different providers; patient opinions on who does and should provide their care; and perceptions of primary care providers’ (PCP) knowledge and skills related to caring for cancer survivors. In addition to data from the 12-month survey, we also collected patient characteristics at study entry, including cancer site and stage from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Result (SEER) tumor registry and demographics, comorbidities, cancer treatment, and insurance type from administrative databases.

Analysis

We compared demographic characteristics of the study population according to cancer type. For categorical variables we used the Chi-square test and for age as a continuous variable we used ANOVA.

For each question related to cancer survivorship on the 12-month survey, we computed frequencies of response categories. The primary goal of this analysis was to describe perspectives overall rather than to compare them across any specific groups. However, in exploratory analyses, we also examined survey results according to: cancer type, age at diagnosis (<65, 65+ years), comorbidity in the year before baseline (Charlson = 0, Charlson = 1, Charlson = 2+), and intervention group. We compared distributions in responses across categories of these variables using the Chi-square test. We also compared patients’ views on PCP knowledge and skills according to whom they indicated as their ideal provider for follow-up care. This analysis excluded the 10 people who reported “other” or “unsure.” We also examined the association between whom patients indicated as their ideal provider for follow-up care and what they discussed with different providers. In exploratory analyses, we limited our analyses to patients who completed treatment at least 6 months before the survey.

Results

Of the 251 participants enrolled in the RCT, 3 disenrolled from the study, 3 refused the 12-month interview, and 10 died within 12 months of diagnosis. Of the 235 remaining people, 230 responded to the 12-month phone survey (Fig. 1). The majority of patients had breast cancer (N = 183, 79.6 %), were non-Hispanic, Caucasian, and had attended at least some college (Table 1). Patients in the intervention group were slightly younger than controls (mean 59.7 vs. 69.4), and had higher levels of educational attainment, and fewer comorbidities (9.1 % vs. 21.4 % with Charlson comorbidity score ≥2). The majority of patients (N = 195, 84.8 %) completed treatment at least 6 months before the survey. However, there were differences by cancer site: lung cancer patients were more likely to not have received treatment or to have undergone treatment longer (Table 1).

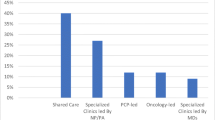

Most patients reported discussing late or long-term side effects with a doctor or healthcare provider (80.9 %) and receiving a written follow-up plan at the end of treatment (76.8 %) (Table 2). The majority considered their cancer specialist (such as medical, radiation, surgical, or gynecological oncologist) to be their main provider for cancer follow-up; however responses differed by cancer type (Table 2). While most patients had discussed with their cancer specialist who would provide cancer follow-up care, 27.9 % had not and 2.6 % were unsure. Only 12.6 % thought the PCP was their ideal provider for their cancer-related follow-up care. Participants who considered their PCP to be their ideal provider of cancer follow-up care were more likely to report confidence in the PCP’s skills, knowledge, and communication (Table 3). Approximately half of patients were uncertain how well their PCP communicated with the oncologist and how knowledgeable s/he was in caring for cancer survivors, with breast cancer patients expressing greater uncertainty (Table 2). Patients in the intervention group were more likely than control participants to have discussed follow-up care with both their cancer provider and other non-PCP providers (results not shown). Approximately half of participants had discussed who would provide their noncancer care. In general, responses did not vary according to randomization group, gender, age, or comorbidities (results not shown). However, patients who indicated their PCP was their ideal doctor for cancer-related follow-up were more likely to report discussions with their oncologist about who would provide their noncancer care (Table 4). There was some suggestion that they were also more likely to have discussed both cancer and noncancer care with their cancer doctor and PCP; however these results were not significant. Discussion of late or long-term effects and receipt of treatment summary or follow-up plan did not differ according to reported ideal doctor for follow-up care (Table 4). None of our results in any of the analyses differed meaningfully when restricted to patients with at least 6 months between their last treatment and their survey (data not shown).

Discussion

We observed that even in an integrated healthcare system centered around primary care, cancer survivors are unsure how well their PCP can care for their cancer. Our results do not suggest that patients lack confidence in their PCP in general, but rather that there is considerable uncertainty about their PCP’s knowledge and skills in follow-up cancer care. In a single site, cross-sectional study of 300 breast cancer patients at an academic breast cancer center in 2007, Mao et al. observed a similar distribution of patient confidence in PCP skills and knowledge related to caring for cancer survivors. Patients in the Mao study were even less confident in their providers than in our study. These findings might explain why in our study and other studies patients prefer seeing cancer specialists for cancer-related follow-up [23, 24].

Our findings are also similar to other studies with respect to reported discussions about who would provide survivorship care. In 2007, Cheung et al. surveyed 535 cancer survivors who were two or more years from diagnosis and who had received at least some of their care at a single academic cancer center [22]. Our observation that approximately 70 % discussed cancer follow-up care with their cancer specialist is consistent with the 65 % who reported a discussion with their oncologist in Cheung et al. These results suggest that nearly one third of patients do not discuss cancer follow-up care with their oncology providers. An even smaller percent discuss their other healthcare needs with their PCPs. The proportion of participants in our study who discussed noncancer-related care with their PCP (39 %) was nearly identical to the proportion in the Cheung study who discussed general care with their PCP (43 %).

Most of the survivorship studies to date, including those described above, have been conducted at academic medical centers or among patients who received at least part of their cancer at an academic medical center. Many US cancer patients do not receive treatment in such settings, so it is important to understand care patterns and needs in community practice. The major strength of the present study is that it was conducted in an integrated healthcare system with a strong primary care focus. Yet, this organizational structure may also limit the generalizability of our findings. It is not clear whether patients receiving traditional fee-for-service care would have similar experiences. Patients in our study were primarily breast cancer survivors participating in a randomized trial and may differ in their perspectives and expectations from members of the general population who choose not to participate in studies. However, given the consistency of our results with other studies, our results may be applicable to other settings.

Overall, our findings suggest that patients prefer receiving cancer follow-up care from a specialist and are unsure of their PCPs’ knowledge and skills in this area. The nurse navigator intervention did not significantly improve patient confidence in PCPs to provide cancer follow-up care. Existing evidence for cancer survivors is limited, but a few trials suggest that outcomes are similar for patients whose follow-up is managed by different providers [25], and observational studies show that patients who see both primary care and oncology providers receive better care [9, 10, 26, 27]; many studies demonstrate the importance of care coordination in chronic disease management [28]. Patient lack of confidence in PCPs may be related to provider attitudes and beliefs. Previous research suggests many PCPs lack confidence in their ability to care for cancer patients, and oncologists also lack confidence in PCPs [14, 29–31]. In a recent, nationally representative survey of providers, only one in three PCPs were confident in their ability to follow breast and colon cancer survivors for recurrence and even fewer (1 in 5) were confident in managing long-term and late effects of cancer [14]. PCPs report playing an active role in cancer-related follow-up [13], but almost half report low knowledge on cancer-related follow-up for breast and colon cancer survivors, compared to 12 % of oncologists [31]. However, other studies have shown PCPs want to be involved in survivorship care [32–34].

One of the study limitations is that we did not ask patients for their opinions on the shared care model or their preference for who would provide noncancer-related care. Nevertheless, the present study highlights an opportunity for future research on interventions to improve survivorship care and coordination or hand-offs between PCPs and cancer specialists. There also is an important opportunity to help patients better understand what their PCPs can and cannot provide in the way of cancer follow-up care and how these providers will communicate with cancer specialists to deliver coordinated care.

References

Institute of Medicine and National Research Council of the National Academies. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Washington: The National Academies Press; 2005.

Earle CC, Ganz PA. Cancer survivorship care: don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(30):3764–8. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.41.7667.

Tessaro I, Campbell MK, Golden S, Gellin M, McCabe M, Syrjala K, et al. Process of diffusing cancer survivorship care into oncology practice. Transl Behav Med. 2013;3(2):142–8. doi:10.1007/s13142-012-0145-4.

Kirsch B. Many US, cancer survivors still lost in transition. Lancet. 2012;379(9829):1865–6.

Salz T, Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS, Layne TM, Bach PB. Survivorship care plans in research and practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012. doi:10.3322/caac.20142.

Sabatino SA, Thompson TD, Smith JL, Rowland JH, Forsythe LP, Pollack L, et al. Receipt of cancer treatment summaries and follow-up instructions among adult cancer survivors: results from a national survey. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(1):32–43. doi:10.1007/s11764-012-0242-x.

Faul LA, Rivers B, Shibata D, Townsend I, Cabrera P, Quinn GP, et al. Survivorship care planning in colorectal cancer: feedback from survivors & providers. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30(2):198–216. doi:10.1080/07347332.2011.651260.

Earle CC, Burstein HJ, Winer EP, Weeks JC. Quality of non-breast cancer health maintenance among elderly breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(8):1447–51. doi:10.1200/jco.2003.03.060.

Snyder CF, Earle CC, Herbert RJ, Neville BA, Blackford AL, Frick KD. Preventive care for colorectal cancer survivors: a 5-year longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(7):1073–9. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.11.9859.

Snyder CF, Earle CC, Herbert RJ, Neville BA, Blackford AL, Frick KD. Trends in follow-up and preventive care for colorectal cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(3):254–9. doi:10.1007/s11606-007-0497-5.

Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5117–24. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0474.

Chubak J, Tuzzio L, Hsu C, Alfano CM, Rabin B, Hornbrook MC, et al. Providing care to cancer survivors in integrated healthcare delivery systems: practices, challenges and research opportunities. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(3):184–9.

Klabunde CN, Han PK, Earle CC, Smith T, Ayanian JZ, Lee R, et al. Physician roles in the cancer-related follow-up care of cancer survivors. Fam Med. 2013;45(7):463–74.

Cheung W, Aziz N, Noone A-M, Rowland J, Potosky A, Ayanian J, et al. Physician preferences and attitudes regarding different models of cancer survivorship care: a comparison of primary care providers and oncologists. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):343–54. doi:10.1007/s11764-013-0281-y.

Reid RJ, Coleman K, Johnson EA, Fishman PA, Hsu C, Soman MP, et al. The group health medical home at year two: cost savings, higher patient satisfaction, and less burnout for providers. Health Aff. 2010;29(5):835–43. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0158.

Nekhlyudov L, Greene SM, Chubak J, Rabin B, Tuzzio L, Rolnick S, et al. Cancer research network: using integrated healthcare delivery systems as platforms for cancer survivorship research. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(1):55–62. doi:10.1007/s11764-012-0244-8.

Horner K, Ludman EJ, McCorkle R, Canfield E, Flaherty L, Min J, et al. An oncology nurse navigator program designed to eliminate gaps in early cancer care. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17(1):43–8. doi:10.1188/13.CJON.43-48.

Wagner EH, Ludman EJ, Aiello Bowles EJ, Penfold R, Reid RJ, Rutter CM et al. Nurse navigators in early cancer care: a randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013; doi:10.1200/jco.2013.51.7359

Mao JJ, Bowman MA, Stricker CT, DeMichele A, Jacobs L, Chan D, et al. Delivery of survivorship care by primary care physicians: the perspective of breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(6):933–8. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0679.

Kent EE, Arora NK, Rowland JH, Bellizzi KM, Forsythe LP, Hamilton AS, et al. Health information needs and health-related quality of life in a diverse population of long-term cancer survivors. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(2):345–52. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2012.08.014.

Cheung WY, Neville BA, Cameron DB, Cook EF, Earle CC. Comparisons of patient and physician expectations for cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(15):2489–95. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.20.3232.

Cheung WY, Neville BA, Earle CC. Associations among cancer survivorship discussions, patient and physician expectations, and receipt of follow-up care. J Clin Oncol. 2010. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.26.4549.

Mayer EL, Gropper AB, Neville BA, Partridge AH, Cameron DB, Winer EP, et al. Breast cancer survivors’ perceptions of survivorship care options. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(2):158–63. doi:10.1200/JCO.2011.36.9264.

Hudson SV, Miller SM, Hemler J, Ferrante JM, Lyle J, Oeffinger KC, et al. Adult cancer survivors discuss follow-up in primary care: ‘Not what I want, but maybe what I need’. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(5):418–27. doi:10.1370/afm.1379.

Howell D, Hack TF, Oliver TK, Chulak T, Mayo S, Aubin M, et al. Models of care for post-treatment follow-up of adult cancer survivors: a systematic review and quality appraisal of the evidence. J Cancer Surviv. 2012. doi:10.1007/s11764-012-0232-z.

Snyder CF, Frick KD, Kantsiper ME, Peairs KS, Herbert RJ, Blackford AL, et al. Prevention, screening, and surveillance care for breast cancer survivors compared with controls: changes from 1998 to 2002. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(7):1054–61. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.18.0950.

Snyder CF, Frick KD, Peairs KS, Kantsiper ME, Herbert RJ, Blackford AL, et al. Comparing care for breast cancer survivors to non-cancer controls: a five-year longitudinal study. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(4):469–74. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-0903-2.

Foy R, Hempel S, Rubenstein L, Suttorp M, Seelig M, Shanman R, et al. Meta-analysis: effect of interactive communication between collaborating primary care physicians and specialists. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(4):247–58. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-152-4-201002160-00010.

Potosky AL, Han PK, Rowland J, Klabunde CN, Smith T, Aziz N, et al. Differences between primary care physicians’ and oncologists’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding the care of cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(12):1403–10. doi:10.1007/s11606-011-1808-4.

Kantsiper M, McDonald EL, Geller G, Shockney L, Snyder C, Wolff AC. Transitioning to breast cancer survivorship: perspectives of patients, cancer specialists, and primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24 Suppl 2:S459–66. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1000-2.

Virgo KS, Lerro CC, Klabunde CN, Earle C, Ganz PA. Barriers to breast and colorectal cancer survivorship care: perceptions of primary care physicians and medical oncologists in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(18):2322–36. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.45.6954.

Bober SL, Recklitis CJ, Campbell EG, Park ER, Kutner JS, Najita JS, et al. Caring for cancer survivors: a survey of primary care physicians. Cancer. 2009;115(18 Suppl):4409–18. doi:10.1002/cncr.24590.

Skolarus TA, Holmes-Rovner M, Northouse LL, Fagerlin A, Garlinghouse C, Demers RY, et al. Primary care perspectives on prostate cancer survivorship: Implications for improving quality of care. Urol Oncol: Sem Orig Investig. 2013;31(6):727–32. doi:10.1016/j.urolonc.2011.06.002.

Del Giudice ME, Grunfeld E, Harvey BJ, Piliotis E, Verma S. Primary care physicians’ views of routine follow-up care of cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2009:JCO.2008.20.4883. doi:10.1200/jco.2008.20.4883.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the nurse navigators: Ellen Canfield, Lynn Flaherty, and Jennifer Min; and Kathryn Horner, Ruth McCorkle PhD, and Eric Chen MD for their leadership in developing the project and supporting the intervention; and Beth Kirlin and Janice Miyoshi for their administrative and data collection support.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (grant number P20CA137219 to EHW). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The collection of cancer stage data used in this study was supported by the Cancer Surveillance System of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, which is funded by Contract No. N01-CN-67009 and N01-PC-35142 from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) Program of the National Cancer Institute with additional support from the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center and the State of Washington.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chubak, J., Aiello Bowles, E.J., Tuzzio, L. et al. Perspectives of cancer survivors on the role of different healthcare providers in an integrated delivery system. J Cancer Surviv 8, 229–238 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0335-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0335-1