Abstract

Purpose

Prior studies indicate that racial disparities are not only present in cancer survival, but also in the quality of cancer survivorship. We estimated the effect of cancer and its treatment on two measures of survivorship quality as follows: health-related quality of life and employment and hours worked for initially employed and insured women newly diagnosed with breast cancer.

Methods

We collected employment data from 548 women from 2007 to 2011; 22 % were African-American. The outcomes were responses to the SF-36, CES-D, employment, and change in weekly hours worked from pre-diagnosis to 2 and 9 months following treatment initiation.

Results

African-American women reported a 2.77 (0.94) and 1.96 (0.92) higher score on the mental component summary score at the 2 and 9 month interviews, respectively. They also report fewer depression symptoms at the 2-month interview, but were over half as likely to be employed as non-Hispanic white women (OR = 0.43; 95 % CI = 0.26 to 0.71). At the 9-month interview, African-American women had 2.33 (1.06) lower scores on the physical component summary score.

Conclusions

Differences in health-related quality of life were small and, although statistically significant, were most likely clinically insignificant between African-American and non-Hispanic white women. Differences in employment were substantial, suggesting the need for future research to identify reasons for disparities and interventions to reduce the employment effects of breast cancer and its treatment on African-American women.

Implications for cancer survivors

African-American breast cancer survivors are more likely to stop working during the early phases of their treatment. These women and their treating physicians need to be aware of options to reduce work loss and take steps to minimize long-term employment consequences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

African-American women have lower breast cancer survival rates than non-Hispanic white women [1, 2]. They also tend to have more advanced stages of breast cancer at diagnosis [2] and are less likely to receive recommended care [2, 3]. Possible explanations for this disparity include lack of health insurance [4] and lower socioeconomic status [3, 5]. Differences in health-related quality of life have also been reported, but the evidence is mixed. Among breast cancer survivors, African-American women have reported worse physical health, but better mental health than their white counterparts [6]. However, when Janz and colleagues included detailed treatment and clinical characteristics in their analysis of women diagnosed with breast cancer, these researchers found no differences in physical well-being between white and African-Americans and better mental health in African-Americans [7].

In addition to subjective measures of quality of life, an objective and relevant outcome for cancer survivors is whether they return to work. Bradley et al. (2005) [8] reported that African-American women were 12 percentage points less likely to be employed than white women 6 months after diagnosis, but by 12 months following diagnosis, racial differences were no longer statistically significant [8]. Demographic characteristics such as age [9, 10] and low education [11–13], chemotherapy [10, 14, 15] and radiation [14], physically demanding jobs and availability of sick leave [11, 16], and work place discrimination and accommodation can all influence return to work [17–19]. If African-American women are diagnosed at later stages, they may require lengthy and toxic chemotherapy regimens, which would prevent them from returning to work relative to women diagnosed with earlier stage disease. Likewise, if employed in physically intense jobs, African-American women may be unable to perform job tasks and require a longer period of recovery or possible job restructuring.

We examine differences between African-Americans and non-Hispanic whites in physical and mental health, depression symptoms, employment, and change in weekly hours worked in initially employed and insured women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. These outcomes were highlighted by the Institute of Medicine as priority areas of investigation for cancer survivors [20]. Examining both subjective and objective measures of functioning provides a more complete picture of outcomes than reported in prior studies. We more thoroughly control for job characteristics (job tasks, employer type and size, job satisfaction, job involvement) than previous studies [14, 21–23] which allows us to determine whether racial differences persist after accounting for differences in job quality. Because all women were initially employed and insured, we reduce bias caused by differences in pre-diagnosis functioning and health insurance coverage, which may also reflect job quality [24, 25] and worker characteristics such as career orientation [10, 24].

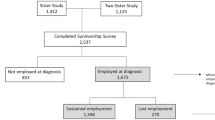

Data

We enrolled 625 employed women (461 non-Hispanic white, 138 African-American, and 26 other race or ethnicity) diagnosed with breast cancer within 2 months of initiating treatment with intent to cure. We collaborated with three hospital-based treatment centers and five private oncology centers from urban and rural areas in Virginia. Women were between the age of 21 and 64 years and because this study was part of a larger study of health insurance and labor supply, women were insured either through their employer or through a spouse's employer [26]. The aims of the study were to compare how women differed in employment, hours worked, and health status by health insurance source. The study team received an administrative supplement to collect similar data from employed and insured unmarried women, which we include in this analysis. We do not make comparisons by health insurance source since all unmarried women are insured by their own employer and instead, we control for marital status.

The study recruitment procedures are described in more detail by Bradley et al. [26]. In summary, we reviewed the records of 5,840 breast cancer patients to identify prospective study subjects. Subjects had to be without metastatic disease and within 2 months following surgery or initiating chemotherapy and/or radiation. Letters were mailed to eligible subjects' physicians (N = 749). Physicians of three subjects refused to allow us to contact their patients. Interviewers telephoned the women to screen for eligibility. The overall participation rate was 80 % and 95 % of enrolled married, and single women were retained during the study period. Due to the small sample size, women categorized as “other” race/ethnicity were excluded from the analysis. An additional 16 non-Hispanic white and 8 African-American women were excluded because their data were incomplete, leaving an analytic sample of 548 women.

We interviewed women via telephone at three time points as follows: (1) at baseline, where women were asked to describe their employment situation just prior to diagnosis, (2) within 2 months following surgery or the initiation of chemotherapy or radiation, and (3) 9 months after initiating treatment. We also extracted information about cancer stage, surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation from women's medical records. The study was approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Review Board (HM10709).

Health status and employment outcomes

Health status was measured by the physical and mental component summary scores (PCS and MCS) and the mental health enhanced score (MHE) from the SF-36 [27] and the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) ten-item scale [28]. Women were asked in the first interview to answer the SF-36 and CES-D questionnaires under the conditions “please indicate how often you felt this way immediately before your diagnosis” and in subsequent interviews to reflect their current situation. Lower scores for the PCS and MCS are indicative of worse outcomes, and higher scores on the MHE and the CES-D scale indicate more depressive symptoms.

We measured employment at the follow-up interviews, change in weekly hours worked for those who were employed relative to the baseline interview, and percent change in weekly hours worked. The percent change in weekly hours work reflects change relative to the initial level of hours worked, rather than absolute change. We defined employment status as a binary variable that is equal to one if a woman reported that she worked for one or more hours for pay.

Control variables

Individual characteristics included age, education, had children under age 18 years, pre-diagnosis annual household income, and marital status. We included variables for breast cancer stage and treatment. Treatment was categorized as either surgery only or had chemotherapy or radiation. We also controlled for job satisfaction prior to diagnosis [29]. All estimations included variables for the year of the interview (2007 through 2011).

Women's job characteristics included whether she worked in a blue or white collar job, firm size, employer type, availability of paid sick leave, and job tasks. Job task questions asked if the woman agreed with statements such as “My job involves a lot of physical effort” for physical effort, lifting heavy loads, stooping, kneeling, crouching, intense concentration/attention, data analysis, keeping up with the pace set by others, learning new things, and whether the job requires good eyesight [30]. We dichotomized responses into all/almost all of the time and most of the time versus some of the time or none/almost none of the time. Subjects also reported the number of hours they spent sitting per day.

Statistical analysis

Patient, job, and disease characteristics, along with the outcomes of interest were analyzed descriptively by race. Statistically significant differences in the means of continuous variables were tested using t tests and differences in the distribution of categorical variables were determined using chi-square tests. We estimated ordinary least squares (OLS) models with robust standard errors clustered at the physician level for the four health status measures at each of the two follow-up interviews, controlling for the baseline scores. Employment was estimated using logistic regression. Odd ratios (OR) and 95 % confidence intervals (CI) are reported. Models of change and percent change in weekly hours worked were estimated using OLS with robust standard errors, controlling for weekly hours worked prior to diagnosis. All analyses were performed in SAS v.9.2 [31].

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 reports descriptive statistics for the sample overall and stratified by non-Hispanic white and African-American women. African-American women were more likely to be unmarried, less educated, have lower annual household income, have children under the age 18 years, and were younger than non-Hispanic white women. Cancer stage and treatment was similar between non-Hispanic white and African-American women. African-American women had a lower PCS score at all three interviews and a higher baseline CES-D score than non-Hispanic white women, indicating worse physical health prior to and following diagnosis and more depression prior to diagnosis. At the 2-month interview, African-American women reported a better MCS score relative to non-Hispanic white women.

Table 2 reports employment and job characteristics. More non-Hispanic white women were employed at the 2- and 9-month interviews. At the 2-month interview, there was a 16 percentage point difference in employment between the non-Hispanic white and African-American women and a 9 percentage point difference in employment at the 9-month interview. Among those employed, weekly hours worked was comparable between African-American and non-Hispanic whites. More African-American women held blue collar jobs, were employed at larger firms, worked for government organizations, and were more likely to receive full or partial paid sick leave than non-Hispanic white women. Women were comparable with respect to hours spent sitting and job tasks (with the exception of holding jobs requiring more physical effort), although African-American women reported lower job satisfaction.

Health status

Table 3 reports OLS regression estimates for PCS, MCS, MHE, and the CES-D at the 2- and 9-month interviews. African-American women had better mental health and depression scores at the 2-month interview relative to non-Hispanic white women. African-American women's MCS score was 2.77 points higher than non-Hispanic white women (p < 0.01). Likewise, African-American women had a lower MHE score (−1.18, p < 0.05) and CES-D score (−1.82, p < 0.01). At the 9-month interview, African-American women reported a lower PCS score (−2.33, p < 0.05), but continued to have a higher MCS score (1.96, p < 0.05) relative to non-Hispanic white women.

Employment and work hours

Table 4 reports estimates for the likelihood of employment and change in weekly hours worked for women who remained employed. At the 2-month interview, African-American women were more than half as likely to be employed as non-Hispanic white women (OR = 0.43; 95 % CI = 0.26, 0.71). By the 9-month interview, the likelihood of employment was lower, but not statistically significant for African-American women. African-American women decreased their hours worked by 2.10 h more than non-Hispanic white women (p < 0.05), although the percent change in weekly hours worked was not statistically significantly different.

Discussion

In a seminal call to action, the Institute of Medicine's report From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor urged for support to cancer survivors who face work-related disabilities. The most substantial finding in our study is that African-American women were more than half as likely to be employed as non-Hispanic white women after controlling for other demographic differences and an extensive list of job characteristics and the availability of paid sick leave. This effect was nearly the same magnitude (OR = 0.57), but was no longer statistically significant at the 9-month interview. Without further research, it is impossible to explain why these large differences occurred, but we speculate that employment differences may be due to treatment differences, both in regimens, length of treatment, and toxicity, and/or perhaps due to differences in symptom control during treatment. Once women return to work, racial differences were not observed in the percent change in weekly hours worked.

Outcomes on health status were remarkably similar between African-American and non-Hispanic white women. Although differences were statistically significant depending on the interview, the differences may not be clinically meaningful. The minimal clinically important difference for the SF-20 domains is reported to be between 3 and 5 points [32], 5 to 12.5 points in chronic lung disease, asthma, and heart disease, depending on the domain [33]. Statistically significant differences in scores between African-American and non-Hispanic white women never exceeded three points and may not be fertile area of research among employed and insured women.

Health care providers need to be aware of the potential for employment loss among African-American women during treatment. These women may need more support in terms of treatment-induced symptoms and their control or more connection to community care giving services. They may also require job rehabilitation services and/or communication with their employer in order to clearly specify treatment, its duration, and short- and long-term impact on work continuation. Once African-American women return to work, they appear to work at the same capacity as other women. However, without support for work continuation, African-American women may disproportionately suffer economic consequences through loss wages, professional and social disruptions due to employment loss, and discontinuity in health insurance coverage, which can impact the quality of the health care they receive.

The study has four main limitations. First, enrollment was confined to initially employed and insured women, all of whom were under 64 years of age. The selection of those who were insured and younger than age 64 may reflect a healthier and more resourced sample than the population of employed breast cancer survivors. Second, we controlled for categories of treatment (e.g., chemotherapy, radiation, surgery only), but did not control for specific regimen or toxicity level. Longer and more toxic regimens can have differing levels of morbidity. Third, the study is confined to a single state, which may limit whether it can be generalized to other settings. To mitigate this possibility, we enrolled subjects from academic and private practices and from rural and urban settings. An advantage of focusing on a single state is that women in the sample were most likely subject to similar economic conditions that may affect employment. Last, dissimilarities between jobs held by non-Hispanic and African-American women are inevitable, in spite of our extensive list of controls for job characteristics.

Our study suggests that among initially employed and insured women, there are few racial differences in health-related quality of life. However, substantial differences in employment are present within 2 months of initiating treatment. By 9 months following treatment initiation, statistical significance was diminished, but the point estimate remained nearly unchanged. These findings are consistent with qualitative studies of African-American women with breast cancer who report that breast cancer interfered with work and that they cannot afford to take time away from work [34, 35]. Future research is needed to determine the reasons for differences in employment rates between African-American and non-Hispanic white women. An understanding of the most salient factors associated with differences in employment can lead to improvements in clinical management. Our study suggests that differences in sick leave and job tasks are insufficient to explain racial differences in employment following the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer. Loss of employment can have a negative impact on the economic viability of women and can affect their ability to retain health insurance to meet their long-term care needs.

References

Chlebowski RT, Chen Z, Anderson GL, et al. Ethnicity and breast cancer: factors influencing differences in incidence and outcome. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:439–48.

Li CI, Malone KE, Daling JR. Differences in breast cancer stage, treatment, and survival by race and ethnicity. Arch Intern Med. 2003;16:49–56.

Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C. Race, socioeconomic status, and breast cancer treatment and survival. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:490–6.

Roetzheim RG, Pal N, Tennant C, et al. Effects of health insurance and race on early detection of cancer. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:1,409–15.

Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. Cancer J Clinicians. 2004;54:78–93.

Paskett ED, Alfano CM, Davidson MA, et al. Breast cancer survivors' health-related quality of life. Cancer. 2008;113:3,222–30.

Janz NK, Mahasin MS, Hawley ST, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in quality of life after diagnosis of breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3:212–22.

Bradley CJ, Bednarek HL, Neumark D. Short-term effects of breast cancer on labor market attachment: results from a longitudinal study. J Health Econ. 2005;24:137–60.

Fantoni SQ, Peugniez C, Duhamel A, Skrzypczak J, Frimat P, Leroyer A. Factors related to return to work by women with breast cancer in northern France. J Occup Rehabil. 2010;20:49–58.

Hoyer M, Nordin K, Ahlgren J, et al. Change in working time in a population-based cohort of patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2853–60.

Torp S, Nielsen RA, Gudbergsson SB, et al. Sick leave patterns among 5-year cancer survivors: a registry-based retrospective cohort study. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6:315–23.

Ahn E, Cho J, Shin DW, et al. Impact of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment on work-related life and factors affecting them. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;116:609–16.

Lauzier S, Maunsell E, Drolet M, et al. Wage losses in the year after breast cancer: extent and determinants among Canadian women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:321–32.

Mujahid MS, Janz NK, Hawley ST, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in job loss for women with breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:102–11.

Johnsson A, Fornander T, Rutqvist LE, Olsson M. Work status and life changes in the first year after breast cancer diagnosis. Work. 2011;38:337–46.

Blinder VS, Patil S, Thind A, et al. Return to work in low-income Latina and non-Latina white breast cancer survivors: a 3-year longitudinal study. Cancer. 2012;118:1664–74.

Bouknight RR, Bradley CJ, Luo Z. Correlates of return to work for breast cancer survivors. J Clin Onc. 2006;24:345–53.

Satariano WA, DeLorenze GN. The likelihood of returning to work after breast cancer. Public Health Rep. 1996;111:236–41.

Carlsen K, Jensen AJ, Regulies R, et al. Self-reported work ability in long-term breast cancer survivors. A population-based questionnaire study in Denmark. Acta Oncol. 2013;52:423–9.

Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. Cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transitions. Washington: The National Academy Press; 2006.

Bradley CJ, Oberst K, Schenk M. Absenteeism from work: the experience of employed breast and prostate cancer patients in the months following diagnosis. Psychooncology. 2006;15:739–47.

Bradley CJ, Neumark D, Luo Z, Schenk M. Employment and cancer: findings from a longitudinal study of breast and prostate cancer survivors. Cancer Invest. 2007;25:47–54.

Short PF, Vasey JJ, Tunceli K. Employment pathways in a large cohort of adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2005;103:1292–301.

Gilleskie DB, Lutz BF. The impact of employer-provided health insurance on a dynamic employment transitions. J of Human Res. 2002;37:129–62.

Kapur K. The impact of health on job mobility: a measure of job lock. Ind Labor Relat Rev. 1998;51:282–98.

Bradley CJ, Neumark D, Barkowski S. Does employer-provided health insurance constrain labor supply adjustments to health shocks? New evidence on women diagnosed with breast cancer. J Health Econ. 2013;32:833–49.

Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M. (eds): SF-36 health survey: manual and interpretation guide. Boston, MA, The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, 1993.

Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1701–4.

Weiss DJ, Dawis RV, England GW. Manual studies in vocational rehabilitation. Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. 1967;22:1–20.

Health and retirement study. (2013). Retrieved from http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/

SAS Institute, Inc, SAS 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 2000–2008.

Samsa GP, Matchar DB. Relationships between test frequency and outcomes of anticoagulation: a literature review and commentary with implications for the design of randomized trials of patients' self-management. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2000;9:283–92.

Wyrwich KW, Tierney WM, Babu AN, Kroenke K, Wolinsky FD. A comparison of clinically important differences in health-related quality of life for patients with chronic lung disease, asthma, or heart disease. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:577–91.

Lewis PE, Sheng M, Rhodes MM, Jackson KE, Schover LR. Psychological concerns of young African-American breast cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2012;30:168–84.

Blinder VS, Murphy MM, Vahdat LT, Gold HT, de Melo-Martin I, Hayes MK, et al. Employment after a breast cancer diagnosis: a qualitative study of ethnically diverse urban women. J Community Health. 2012;37:763–72.

Acknowledgments

Bradley's research was supported by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) grant number R01-CA122145, “Health, Health Insurance, and Labor Supply.” The authors are grateful to Myra Owens, Ph.D. and Mirna Hernandez for project coordination, Meryl Motika and Scott Barkowski for programming support, the interviewers and medical record auditors that collected the data, and the many subjects who generously donated their time to the project. There are no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest for this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bradley, C.J., Wilk, A. Racial differences in quality of life and employment outcomes in insured women with breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv 8, 49–59 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0316-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-013-0316-4