Abstract

Objectives

Recent advances in the management of early-stage non-small cell lung cancer have focused on less invasive anesthetic and surgical techniques. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery without tracheal intubation is an evolving technique to provide a safe alternative with less short-term complication and faster postoperative recovery. The purpose of this review was to explore the latest developments and future prospects of nonintubated thoracoscopic surgery for early lung cancer.

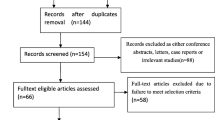

Methods

We examined various techniques and surgical procedures as well as the outcomes and benefits.

Results

The results indicated a new era of video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery in which there is reduced procedure-related injury and enhanced postoperative recovery for lung cancer.

Conclusions

Nonintubated thoracoscopic surgery is a safe and feasible minimally invasive alternative surgery for early non-small cell lung cancer. Faster recovery and less short-term complication are potential benefits of this approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Surgery is currently the standard curative treatment for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). In the past two decades, thoracic surgeons have sought for different minimally invasive techniques such as video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) to decrease the invasiveness of surgery. Aside the improvement of surgical techniques and instruments, precise and less invasive anesthesia for lung cancer surgery to enhance recovery is gaining attention. Since the invention of endotracheal tubes, bronchial blockers, and double-lumen tubes in the first half of the twentieth century, endotracheal intubation with selective one-lung ventilation and deeper level of general anesthesia has been considered routine for lung surgery [1]. In the era of VATS, Pompeo et al. first described the technique of awake thoracoscopic resection of solitary pulmonary nodules without tracheal intubation in 2004 [2]. In 2011, Chen et al. reported the first series of nonintubated thoracoscopic lobectomy for lung cancer, including a detailed description of the anesthetic and surgical technique [3]. Subsequently, a nonintubated technique was also applied on VATS segmentectomy [4] and uniportal VATS lobectomy [5]. The purpose of this review was to explore the latest developments and future prospects of nonintubated thoracoscopic surgery for early lung cancer.

Definition

Nonintubated surgery indicates the avoidance of endotracheal intubation during surgery. However, there is no universally accepted definition of the associated airway management, analgesic technique, and sedation level. Usually, because of the absence of tracheal intubation, muscle relaxants are not used, and the depth of anesthesia can be decreased. In some studies, the term “awake VATS” was used to describe the consciousness of the patient, in which no or minimal sedation is applied [2, 6, 7].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for nonintubated surgery for early-stage lung cancer

Currently, there are no standardized selection criteria for nonintubated VATS (NIVATS) for early NSCLC, and the indication varies in different institutes. Common inclusion criteria include clinical stage I or II NSCLC tumors smaller than 6 cm in diameter, without evidence of chest wall, diaphragm, or main bronchus involvement, and patients with severe comorbidities that increase the risk of intubated general anesthesia [3, 8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Contraindications include body mass index (BMI) greater than 30, expected difficult airway, expected extensive pleural adhesion, high risk of gastric reflux, severe cardiopulmonary dysfunction, persistent cough or excessive airway secretion, unfavorable anatomical conditions, and coagulopathy that may be contraindicated for planned regional anesthesia [3, 8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

Anesthetic considerations of NIVATS

Airway management

As previously mentioned, NIVATS describes anesthetic and surgical techniques that avoid the use of an endotracheal tube. Support of oxygenation and ventilation varies between studies, and can be provided by a simple oxygen facemask, laryngeal mask airway (LMA), or high-flow nasal cannula (HFNC). Face mask is the most commonly used device in early NIVATS studies. In a pilot study on NIVATS lobectomy for lung cancer, Chen et al. selected patients with good cardiopulmonary reserve to prevent respiratory failure. The result showed that in most of the nonintubated patients, SpO2 could be maintained at 90% or above with a face mask during the entire operation, and hypercapnia noted in some patients was permissive [3]. However, hypoxia and hypoventilation remain a concern especially in prolonged operation and in patients with higher respiratory risk. LMA is a solution to this problem. LMA provides a more secure airway with satisfactory result under spontaneous breathing even for old patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or for obese patients [16]. LMA also allows inhalation anesthesia, permits positive pressure ventilation if indicated, and facilitates conversion to tracheal intubation in a lateral decubitus position if indicated. High-flow nasal cannula is another choice to effectively increase oxygen reserve during NIVATS [17] (Table 1) (Fig. 1).

Anesthetic techniques

Anesthetic techniques for NIVATS usually include a locoregional anesthesia for pain control and supplemental sedation. For pain control, thoracic epidural anesthesia (TEA) and intrathoracic intercostal nerve block (ICNB) are most commonly applied. Pompeo et al. described numerous minor NIVATS procedures using thoracic epidural anesthesia with the catheter inserted at the T4/T5 level to achieve somatosensory motor block at the T1–T8 level with preservation of diaphragm movement [2, 18, 19]. Subsequently, Chen et al. reported a series of nonintubated thoracoscopic lobectomies for lung cancer performed with an epidural catheter inserted at the T5/T6 level to achieve sensory block between T2 and T9 [3]. Other researchers also described similar TEA technique in NIVATS [6, 20, 21]. Intercostal nerve block (ICNB) is a simpler, safe and effective alternative for pain control [20, 22,23,24]. ICNB is usually performed intrathoracically. After creation of thoracoscopic ports under local anesthesia, the third to eighth intercostal nerves are injected with local anesthetic agents such as bupivacaine under direct thoracoscopic vision (Fig. 2a). ICNB also has benefits of shorter anesthetic induction duration and unilateral block without systemic adverse effects [20]. Other regional techniques include paravertebral block and serratus anterior plane block [24, 25]. In a randomized controlled study comparing paravertebral block versus ICNB in nonintubated uniportal VATS, both regional blocks had an anesthetic sparing effect, and faster postoperative recovery compared to general anesthesia alone [26].

Cough suppression and vagal nerve block

Lung cancer surgery usually involves hilum manipulation and mediastinal lymph node dissection, which may predispose to the cough reflex during the operation. Although some authors had reported NIVATS lobectomy without vagus blockade [27], we routinely perform vagal nerve block for NIVATS lung cancer surgery to avoid unexpected coughing [3, 22]. The procedure is performed by the infiltration of local anesthetic agents such as bupivacaine 0.5% or lidocaine adjacent to the vagus nerve at the level of the lower trachea for the right-side operation and at the level of the aortopulmonary window for the left-sided operation at the beginning of the operation (Fig. 2b) [3]. This technique facilitates the dissection of bronchus and vessels at the lung hilum and makes NIVATS anatomical resection easier.

Sedation

Although NIVATS can be performed with the patient awake or under minimal sedation in minor procedures [2, 19, 28,29,30], for lung cancer surgery, considering the longer operation duration and more advanced surgical technique, moderate to deep sedation is favored in most surgical teams to provide a stable operation field and to decrease patient anxiety and discomfort. In an earlier study by Chen et al., sedation was performed by intravenous administration of propofol using a target-controlled infusion method to maintain the patient in mild sedation but able to communicate and cooperative (Ramsay sedation score III) [3]. Later studies mostly used propofol in combination with remifentanil or dexmedetomidine to achieve a deep sedation (or general anesthesia) level (bispectral index 40–60) with preservation of spontaneous breathing [10, 11, 13,14,15]. General anesthesia can also be provided with volatile anesthetic gases such as sevoflurane if LMA is used [5, 31].

Feasibility of various NITS surgical procedures for early NSCLC

Lobectomy

For early NSCLC, lobectomy in combination with systematic mediastinal lymph nodes remain the standard treatment for most surgeons. In earlier development of “awake VATS”, for undetermined lung nodules, only wedge resection was performed, and the operation may be converted to intubated general anesthesia if unexpected malignant lesions were found intraoperatively, which indicated the need for subsequent lobectomy [2]. VATS lobectomy without tracheal intubation was first described in 2007 using mild sedation and TEA [6]. In 2011, Chen et al. described 30 patients with stage I or II NSCLC treated by NIVATS lobectomy, using a combination of TEA and intrathoracic vagal block to achieve effective cough suppression [3]. In their study, 3 (10%) patients undergoing NIVATS lobectomy required conversion to tracheal intubation, while the anesthesia duration, surgical duration, blood loss, and number of dissected lymph nodes were comparable in both the intubated and nonintubated groups. The results showed the feasibility and safety of more extensive pulmonary dissections and expanded the application of NIVATS for lung cancer. Thereafter, other surgical teams also reported modified anesthetic techniques and airway management for NIVATS lobectomy with successful results [10, 11, 13, 14, 21]. Apart from the regional blocks, the surgical technique of NIVATS is generally similar to intubated VATS lobectomy.

Sublobar resections

Sublobar resections, including anatomical segmentectomies or wedge resections, are alternatives in selective early lung cancer patients. For example, patients with poor pulmonary function who cannot tolerate a lobectomy [32], those with other comorbidities prohibitive for lobectomy [33], or patients with less aggressive lung cancer such as minimally invasive adenocarcinoma or adenocarcinoma in situ [34] may benefit from sublobar resections. In 2013, Hung et al. first reported 21 patients with lung tumors, including 16 primary NSCLC, who underwent NIVATS segmentectomy using a combination of TEA, intrathoracic vagal blockade, and target-controlled sedation. The operative and anesthetic results were satisfactory. The feasibility and safety of the procedure were also proven by other thoracic study groups using similar techniques [35, 36]. Compared with intubated VATS segmentectomy, NIVATS had comparable short-term outcomes, including surgical duration, intraoperative blood loss, postoperative chest tube drainage amount, and number of dissected lymph nodes, but faster postoperative recovery such as resumption of oral intake, shorter duration of chest tube drainage, and less cost of anesthesia [36].

Wedge resections under nonintubated anesthesia are easier to perform compared to anatomical resections concerning the avoidance of hilum and vessel dissection. Early-stage small lung cancers consisting of ground glass opacities (GGOs) are diagnosed increasingly because of widespread use of low-dose computed tomography screening and high-resolution computed tomography. Considering the low invasiveness and longer survival of these lesions, limited pulmonary resection and less invasive surgical approach have increased in popularity, and experiences with NIVATS wedge resection for early NSCLC have also been reported in large volume centers [15, 37, 38]. A novel “tubeless” approach (no endotracheal tube, chest tube, or urinary catheterization) has emerged as a modification of minimally invasive surgery [39, 40]. Patients who underwent the tubeless approach for wedge resection experienced less pain and shorter hospital stay. Although tubeless thoracic surgery is still evolving, it may be an alternative for fast-tract early lung cancer surgery in selected patients in the future.

Uniportal surgery

In recent years, with the advancements of surgical instrument and video systems, VATS has evolved from a multiport approach to a single-port approach with advantages of reduced postoperative pain, residual paresthesia, and hospital stay [41, 42]. NIVATS can also be performed with a single-port (uniportal) setting [41, 42]. In 2014, Gonzalez-Rivas et al. first described a case of nonintubated single-port lobectomy under epidural anesthesia, which represented a less invasive approach to lobectomy for lung cancer [5]. Since then, different techniques of uniportal NIVATS for major and minor pulmonary resections have been widely reported by other authors and this has started a new era of NIVATS for lung cancer [10, 14, 38, 43,44,45,46].

Conversion to tracheal intubation

A major concern in the nonintubated approach for thoracic surgery is that it necessitates conversion to tracheal intubation. The conversion rate ranges from 2 to 10% [3, 9, 11,12,13,14, 37], which depends on the procedure type and the experience of the team. Although it is uncommon, to ensure patient safety, a clearly defined protocol for elective or urgent intubation must be set up. Common causes of conversion are persistent hypoxemia, profound mediastinal movement, dense pleural adhesion, or major bleeding. The collaboration of the entire surgical team is important, and anesthesiologists should be familiar with tracheal intubation in a lateral decubitus position while surgeons should focus on bleeding control and prevention of unnecessary procedures until a secure airway is established. In our institute, anesthesiologists intubate the patient under bronchoscopic guidance followed by insertion of a bronchial blocker in a lateral decubitus position [3]. Double-lumen intubation without changing position is also feasible with appropriate positioning of the head before the operation [47]. Hung et al. reported 1025 patients who underwent NIVATS for lung tumors within a 7-year period in a single institute and found that body mass index (BMI) ≥ 25 kg/m2 and pulmonary anatomical resection were risk factors for conversion to intubation [37]. The conversion rate also decreased over time (from 8.8% in 2009 to 0% in 2016), indicating the learning curve of surgical teams and improving patient selection policies.

Safety and benefits of NIVATS versus intubated thoracoscopic surgery

The safety of NIVATS has been reported by different study groups, with comparable morbidity rate compared to intubated VATS and no perioperative mortality [8, 9, 11, 13, 14, 21, 35, 37]. Meta-analyses showed that NIVATS under regional or local anesthesia provides shorter operating room time, shorter hospital stay, faster postoperative recovery, and less short-term complication compared to intubated VATS [48,49,50]. The benefits of NIVATS may be due to the avoidance of intubation-related complication and one-lung ventilation, and ventilator-related stress hormone release [51,52,53,54]. In patients with increased risk of intubated general anesthesia such as elderly individuals or patients with extremely poor respiratory performance, NIVATS may also provide an alternative approach to decrease postoperative complications and enhance recovery [8, 55,56,57].

Long-term oncological result of NIVATS for early NSCLC

Although faster postoperative recovery has been reported as a short-term benefit of the nonintubated approach for lung cancer, there is no available data regarding long-term oncological outcomes such as survival and recurrence. Some theoretical advantages of the oncological outcome of NIVATS is the reduction of ventilator-related stress and lesser need for opioids, which are believed to preserve perioperative anticancer immunosurveillance [51,52,53,54]. However, further clinical studies with longer follow-up are required to provide more evidence.

Summary

Nonintubated thoracoscopic surgery is a safe and feasible minimally invasive alternative surgery for early NSCLC. Various procedures including lobectomy, segmentectomy, wedge resection, and uniportal VATS can be performed without tracheal intubation. Faster recovery and less short-term complication are potential benefits, while further studies are required to clarify its long-term oncological outcomes.

References

Brodsky J, Lemmens H. The history of anesthesia for thoracic surgery. Minerva Anestesiol. 2007;73:513–24.

Pompeo E, Mineo D, Rogliani P, Sabato AF, Mineo TC. Feasibility and results of awake thoracoscopic resection of solitary pulmonary nodules. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1761–8.

Chen JS, Cheng YJ, Hung MH, Tseng YD, Chen KC, Lee YC. Nonintubated thoracoscopic lobectomy for lung cancer. Ann Surg. 2011;254:1038–43.

Hung MH, Hsu HH, Chen KC, Chan KC, Cheng YJ, Chen JS. Nonintubated thoracoscopic anatomical segmentectomy for lung tumors. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:1209–15.

Gonzalez-Rivas D, Fernandez R, de la Torre M, Rodriguez J, Fontan L, Molina F. Single-port thoracoscopic lobectomy in a nonintubated patient: the least invasive procedure for major lung resection? Interact Cardiov Th. 2014;19:552–5.

Al-Abdullatief M, Wahood A, Al-Shirawi N, Arabi Y, Wahba M, Al-Jumah M, et al. Awake anaesthesia for major thoracic surgical procedures: an observational study. Eur J Cardio-thorac. 2007;32:346–50.

Rocco G, Romano V, Accardo R, Tempesta A, Manna C, Rocca A, et al. Awake single-access (uniportal) video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for peripheral pulmonary nodules in a complete ambulatory setting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:1625–7.

Wu CY, Chen JS, Lin YS, Tsai TM, Hung MH, Chan K, et al. Feasibility and safety of nonintubated thoracoscopic lobectomy for geriatric lung cancer patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:405–11.

Liu J, Cui F, Pompeo E, Gonzalez-Rivas D, Chen H, Yin W, et al. The impact of non-intubated versus intubated anaesthesia on early outcomes of video-assisted thoracoscopic anatomical resection in non-small-cell lung cancer: a propensity score matching analysis. Eur J Cardio-thorac. 2016;50:920–5.

Furák J, Szabó Z, Horváth T, Géczi T, Pécsy B, Németh T, et al. Non-intubated, uniportal, video assisted thoracic surgery [VATS] lobectomy, as a new procedure in our department. Magyar Sebeszet. 2017;70:113–7.

AlGhamdi M, Lynhiavu L, Moon Y, Moon M, Ahn S, Kim Y, et al. Comparison of non-intubated versus intubated video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy for lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:4236–43.

Wang ML, Hung MH, Hsu HH, Chan KC, Cheng YJ, Chen JS. Non-intubated thoracoscopic surgery for lung cancer in patients with impaired pulmonary function. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7:40.

Moon Y, AlGhamdi ZM, Jeon J, Hwang W, Kim Y, Sung S. Non-intubated thoracoscopic surgery: initial experience at a single center. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:3490–8.

Ahn S, Moon Y, AlGhamdi ZM, Sung S. Nonintubated uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a single-center experience. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;51:344–9.

Tsai TM, Lin MW, Hsu HH, Chen JS. Nonintubated uniportal thoracoscopic wedge resection for early lung cancer. J Vis Surg. 2017;3:155.

Ambrogi M, Fanucchi O, Gemignani R, Guarracino F, Mussi A. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery with spontaneous breathing laryngeal mask anesthesia: preliminary experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:514–5.

Wang ML, Hung MH, Chen JS, Hsu HH, Cheng YJ. Nasal high-flow oxygen therapy improves arterial oxygenation during one-lung ventilation in non-intubated thoracoscopic surgery. Eur J Cardio-thorac. 2018;53:1001–6.

Pompeo E. Awake thoracic surgery—is it worth the trouble? Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;24:106–14.

Pompeo E, Rogliani P, Cristino B, Schillaci O, Novelli G, Saltini C. Awake thoracoscopic biopsy of interstitial lung disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:445–52.

Hung MH, Chan KC, Liu YJ, Hsu HH, Chen KC, Cheng YJ, et al. Nonintubated thoracoscopic lobectomy for lung cancer using epidural anesthesia and intercostal blockade. Medicine. 2015;94:e727.

Liu J, Cui F, Li S, Chen H, Shao W, Liang L, et al. Nonintubated video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery under epidural anesthesia compared with conventional anesthetic option. Surg Innov. 2015;22:123–30.

Hung MH, Hsu HH, Chan KC, Chen KC, Yie JC, Cheng YJ, et al. Non-intubated thoracoscopic surgery using internal intercostal nerve block, vagal block and targeted sedation. Eur J Cardiothorac. 2014;46:620–5.

Irons J, Martinez G. Anaesthetic considerations for non-intubated thoracic surgery. J Vis Surg. 2016;2:61.

Kiss G, Castillo M. Non-intubated anesthesia in thoracic surgery-technical issues. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3:109.

Piccioni F, Langer M, Fumagalli L, Haeusler E, Conti B, Previtali P. Thoracic paravertebral anaesthesia for awake video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery daily. Anaesthesia. 2010;65:1221–4.

Mogahed MM, Elkahwagy MS. Paravertebral block versus intercostal nerve block in non-intubated uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery: a randomised controlled trial. Heart Lung Circ. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2019.04.013.

Gonzalez-Rivas D, Fernandez R, de la Torre M, Bonome C. Uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic left upper lobectomy under spontaneous ventilation. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:494–5.

Pompeo E, Tacconi F, Frasca L, Mineo TC. Awake thoracoscopic bullaplasty. Eur J Cardiothorac. 2011;39:1012–7.

Pompeo E, Tacconi F, Mineo D, Mineo T. The role of awake video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery in spontaneous pneumothorax. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:786–90.

Passera E, Rocco G. Awake video-assisted thoracic surgery resection of lung nodules. Video Assisted Thorac Surg. 2018;3:3.

Ambrogi MC, Fanucchi O, Korasidis S, Davini F, Gemignani R, Guarracino F, et al. Nonintubated thoracoscopic pulmonary nodule resection under spontaneous breathing anesthesia with laryngeal mask. Innov Technol Tech Cardiothorac Vasc Surg. 2014;9:276–80.

Macke RA, Schuchert MJ, Odell DD, Wilson DO, Luketich JD, Landreneau RJ. Parenchymal preserving anatomic resections result in less pulmonary function loss in patients with Stage I non-small cell lung cancer. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;10:49.

Gulack BC, Yang CF, Speicher PJ, Yerokun BA, Tong BC, Onaitis MW, et al. A risk score to assist selecting lobectomy versus sublobar resection for early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102:1814–20.

Hattori A, Matsunaga T, Takamochi K, Oh S, Suzuki K. Indications for sublobar resection of clinical stage IA radiologic pure-solid lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;154:1100–8.

Guo Z, Shao W, Yin W, Chen H, Zhang X, Dong Q, et al. Analysis of feasibility and safety of complete video-assisted thoracoscopic resection of anatomic pulmonary segments under non-intubated anesthesia. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6:37–44.

Guo Z, Yin W, Pan H, Zhang X, Xu X, Shao W, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery segmentectomy by non-intubated or intubated anesthesia: a comparative analysis of short-term outcome. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:359–68.

Hung WT, Hung MH, Wang ML, Cheng YJ, Hsu HH, Chen JS. Nonintubated thoracoscopic surgery for lung tumor: 7 years’ experience with 1025 cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107:1607–12.

Hung WT, Hsu HH, Hung MH, Hsieh PY, Cheng YJ, Chen JS. Nonintubated uniportal thoracoscopic surgery for resection of lung lesions. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:S242–50.

Yang SM, Wang ML, Hung MH, Hsu HH, Cheng YJ, Chen JS. Tubeless uniportal thoracoscopic wedge resection for peripheral lung nodules. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;103:462–8.

Lirio F, Galvez C, Bolufer S, Corcoles J, Gonzalez-Rivas D. Tubeless major pulmonary resections. J Thorac Dis. 2018;1:S2664–70.

Jutley R, Khalil M, Rocco G. Uniportal vs standard three-port VATS technique for spontaneous pneumothorax: comparison of post-operative pain and residual paraesthesia. Eur J Cardiothorac. 2005;28:43–6.

Chen PR, Chen CK, Lin YS, Huang HC, Tsai JS, Chen CY, et al. Single-incision thoracoscopic surgery for primary spontaneous pneumothorax. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;6:58.

Galvez C, Navarro-Martinez J, Bolufer S, Lirio F, Sesma J, Corcoles J. Nonintubated uniportal VATS pulmonary anatomical resections. J Vis Surg. 2017;3:120.

Galvez C, Navarro-Martinez J, Bolufer S, Sesma J, Lirio F, Galiana M, et al. Non-intubated uniportal left-lower lobe upper segmentectomy (S6). J Vis Surg. 2017;3:48.

Gonzalez-Rivas D, Yang Y, Guido W, Jiang G. Non-intubated (tubeless) uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic lobectomy. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;5:151–3.

Hung MH, Cheng YJ, Hsu HH, Chen JS. Nonintubated uniportal thoracoscopic segmentectomy for lung cancer. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:e234–5.

Navarro-Martinez J, Galvez C, Rivera-Cogollos M, Galiana-Ivars M, Bolufer S, Martínez-Adsuar F. Intraoperative crisis resource management during a non-intubated video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery. Ann Transl Med. 2015;3:111.

Zhang K, Chen HG, Wu WB, Li XJ, Wu YH, Xu JN, et al. Non-intubated video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery vs intubated video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for thoracic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 1684 cases. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:3556–68.

Bertolaccini L, Zaccagna G, Divisi D, Pardolesi A, Solli P, Crisci R. Awake non-intubated thoracic surgery: an attempt of systematic review and meta-analysis. Video Assisted Thorac Surg. 2017;2:59.

Deng HY, Zhu ZJ, Wang YC, Wang WP, Ni PZ, Chen LQ. Non-intubated video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery under loco-regional anaesthesia for thoracic surgery: a meta-analysis. Interact Cardiov Th. 2016;23:31–40.

Tønnesen E, Höhndorf K, Lerbjerg G, Christensen N, Hüttel MS, Andersen K. Immunological and hormonal responses to lung surgery during one-lung ventilation. Eur J Anaesth. 1993;10:189–95.

Cheng YJ, Chan KC, Chien CT, Sun WZ, Lin CJ. Oxidative stress during 1-lung ventilation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:513–8.

Vanni G, Tacconi F, Sellitri F, Ambrogi V, Mineo T, Pompeo E. Impact of awake videothoracoscopic surgery on postoperative lymphocyte responses. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:973–8.

Tacconi F, Pompeo E, Sellitri F, Mineo TC. Surgical stress hormones response is reduced after awake videothoracoscopy. Interact Cardiov Th. 2010;10:666–71.

Kiss G, Claret A, Desbordes J, Porte H. Thoracic epidural anaesthesia for awake thoracic surgery in severely dyspnoeic patients excluded from general anaesthesia. Interact Cardiov Th. 2014;19:816–23.

Pompeo E, Tacconi F, Mineo TC. Comparative results of non-resectional lung volume reduction performed by awake or non-awake anesthesia. Eur J Cardiothorac. 2011;39:e51–8.

Pompeo E, Rogliani P, Tacconi F, Dauri M, Saltini C, Novelli G, et al. Randomized comparison of awake nonresectional versus nonawake resectional lung volume reduction surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143(47–54):54.e1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hung, WT., Cheng, YJ. & Chen, JS. Nonintubated thoracoscopic surgery for early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 68, 733–739 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11748-019-01220-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11748-019-01220-5