Abstract

Distinctions in the attributes of niche versus mainstream brands are leveraged to explain differences in the drivers of online review ratings. Specifically, we examine how customer review valence, professional critics review valence, community characteristics, location similarity, and reviewer characteristics may impact a reviewer’s rating. We use a unique dataset on the U.S. beer product category to address our research questions and find that niche brands are more impacted by OWOM activity across the board because consumers are less likely to have established brand awareness and brand imagery formed. Likewise, a reviewer is prone to rating a local niche brand more favorably. Professional critics are generally less influential than the online community for the typical focal reviewer. A prior review from the online community becomes particularly influential when its expertise is high and/or when the prior reviewer has shared geographic locational traits with the focal reviewer. Reviewers that engage more with products/brands tend to align sentiments with professional critics, while those that engage more with the online community tend to align sentiment with that community. Utilizing insights from these results, we provide several guidelines for brand managers in devising appropriate social media strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Do the processes and dynamics underpinning consumer product perceptions systematically differ in niche markets compared to mainstream markets? Strictly speaking, niche markets (i.e., areas of a given market that serve customers whose needs are not met by mainstream brands) have always existed. However, their popularity appears to be on the rise with respect to consumer preferences as well as theoretical inquiry across a broad range of disciplines. Relatedly, there is also increased attention on, and demand for, identity-driven niche offerings such as organic foods, farm-to-table restaurants, craft beer, artisanal chocolate, and third wave coffee. Importantly, and in parallel to this dynamic, another process has emerged which has allowed these niche brands to flourish, and even to challenge more mainstream competitors’ market positions across a broad range of consumer markets: online word of mouth (OWOMFootnote 1).

The extant literature in this domain suggests that two key sources of OWOM have a particularly strong influence on consumer product perceptions and consumer decision making: customer review valence and professional critics review valence. Customer review valence, or the average rating assigned to the product/brand in question by prior customer reviewers in the online community, is well-documented to positively influence both consumer product perceptions (Moon et al., 2010; Yin et al., 2016) and, ultimately, market performance of products/brands/firms (Godes & Mayzlin, 2009; Gopinath et al., 2014; Luo, 2009). Professional critics review valence, which is the average product/brand rating assigned by professionally designated reviewers within the product category, has also been established as a powerful informational cue for market consumers that informs their attitudinal formations and purchase decisions (Basuroy et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2012). Yet, while both of these constructs have been shown to positively influence consumers’ product perceptions, a number of important and unanswered questions remain in this stream of research. For example: (1) Which OWOM influencer is stronger in its magnitude of impact overall? (2) Are there key contexts in which additional nuance may be needed to carefully understand these relationships? Research to date has found some mixed results as to whether professional critics or customer review valence may more heavily influence the focal individual (Chakravarty et al., 2010; Tsao, 2014).

This study seeks to address this gap, and build on these lines of inquiry related to the role of the online community versus professional critics, by disentangling how they differentially impact niche and mainstream brands (Jarvis & Goodman, 2005; Zhu & Zhang, 2010). We add further nuance by also considering key moderators that have drawn recent attention across the broader related literature, including: (1) brand location similarity (Becker et al., 2019; Beverland, 2005), (2) community characteristics (Lee et al., 2015; Yazdani et al., 2018), and (3) reviewer characteristics (Sunder et al., 2019; Wilson et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2020). Specifically, we combine theoretical insights from the literatures on brand authenticity (Beverland, 2005) and online word of mouth (OWOM) to generate these key predictions of interest about moderating effects. In doing so, we offer a theoretical rationale for distinguishing between niche and mainstream markets that jointly accounts for location-specific explanations (that are less developed in the OWOM literature), as well as relevant online dynamics such as customer vs. professional critics valence (which adds to the authenticity literature). Taken together, we address key questions related to how a reviewer’s online rating may be affected by the brand’s status as niche or mainstream, the influencing perspectives of customer review valence and professional critics review valence, and key additional moderating factors (brand location similarity, community characteristics, reviewer characteristics).

To empirically test our developed hypotheses, we utilize online community and professional critics review data from the U.S. beer industry that, according to the Brewer’s Association (www.brewersassociation.org), is a $100 billion industry. This product category has multiple intriguing features that leave it well suited for a study that contrasts niche and mainstream brands. For example, the niche segment of the market has experienced substantial levels of growth over the past two decades, which has important practical implications for how these niche brands are perceived by consumers in the face of this growth (Solomon & Mathias, 2020; Verhaal & Dobrev, 2020). The result is a product category that is characterized by strong consumer sentiment and, within the niche market, a strong collective and oppositional identity shared among brands and consumers alike (Frake, 2017; Mathias et al., 2018). Commonly referred to as the long tail of the sales distribution, niche brands/products have received considerable interest by marketing area researchers (Brynjolfsson et al., 2011; Zhu & Zhang, 2010) in other product categories as well. We contribute to these research streams utilizing a comprehensive dataset, which contains 14,356 unique products, spanning 102 distinct product styles that are marketed by 1380 brands.

Our study makes three important contributions, the first of which is to establish that OWOM influences individual reviewer ratings more for niche brands than for mainstream brands. Importantly, this is true in the case of both customer and professional critics review valence. Niche brand status also serves to further accentuate the impacts of other key studied factors including brand location similarity, community expertise, community location similarity, reviewer category experience, and reviewer community engagement. In this vein, our study invokes long tail theory, which has shown that niche brands/products have commanded stronger market positions and enjoyed increased sales performance as consumer search costs have lowered in digital channels (Anderson, 2006; Brynjolfsson et al., 2011; Choi & Bell, 2011). This has only increased recently with wide scale adoption of mobile technologies (Lamberton & Stephen, 2016). Our results confirm and extend these arguments by showing that niche brands do have more to gain from the increased flow of information, in large part because it helps these smaller niche brands avoid falling into the cracks of information exchange interface between firms and consumers, in effect giving them an amplified platform to compete on more equal footing relative to mainstream brands. Theoretical insights related to niche markets and OWOM generated by this research also contribute to the growing body of work in both marketing and management related to organizational and brand authenticity (Beverland, 2005; Verhaal et al., 2017; Weber et al., 2008). In particular, we suggest that the concept of localness (specifically, brand-reviewer and community-reviewer location similarity) serves as a mechanism driving consumer perceptions of authenticity, and ultimately individual review level valence. Thus, our theoretical linkages between OWOM and authenticity, specifically related to location similarity, represents a unique contribution to an emerging stream of research.

The second key contribution is to the OWOM literature as we uncover a considerably stronger positive influence of customer review valence than professional critics review valence on the rating of a focal review. It may come as a surprise that in their search for useful product information, consumers trust the opinions and recommendations of their amateur peers over the professional critics that may be assumed to have greater expertise and more informative opinions about the product category. However, we bolster our finding by leveraging existing theories on homophily (Laumann, 1966; Rogers, 1983) and in-group/out-group effects (Frenzen & Nakamoto, 1993; Granovetter, 1973; Reingen et al., 1984; Susarla et al., 2012) to better articulate the theoretical importance of our findings. It also aligns with some recent aggregate-level empirical results (Chakravarty et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2012; Tsao, 2014). Our results extend these theories further by establishing that online communities may be more tightly connected and have more relevant network contacts than professional critics for the average market consumer. Our extended set of findings also confirms that customer reviews are even more influential when the community has high levels of experience and/or when the focal reviewer has shared geographic traits with other reviewers in the community, adding further nuance to our collective understanding of how these underlying theoretical mechanisms operate in OWOM contexts.

The final key theoretical contribution to the OWOM domain emerges from our findings that reveal different impacts for reviewer category experience and reviewer community engagement. Reviewers that engage with the online community through posting to message boards are more likely to form stronger bonds with that community. By contrast, reviewers that become more experienced in the product category through consuming products and brands, and subsequently generating more review content, are more likely to align instead with the perspectives of professional critics within the category. The tension between community and professional critics influence is motivated by an individual’s competing priorities of gaining inclusion in the online community and establishing one’s own distinction from that community (Snyder, 1992; Tian et al., 2001). Our findings add to a growing body of related research (Chakravarty et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2015; Moe & Schweidel, 2012; Sunder et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020) and extend established theory by showing that the way in which a consumer becomes more involved with a product category over time matters. This has substantial implications for how individuals evolve as both a consumer of the category as well as a member of the online community. It also has significant practical implications for managers.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. We now provide a research background. In the next section, we discuss the relevant literature and present our hypotheses of interest. The fourth section describes the data and variables for the beer industry. The fifth section provides methodological details and an overview of our econometric model with a discussion of how we deal with endogeneity using Gaussian copulas and presents the results. General discussion, managerial implications, and study limitations are in the final section.

Research background

Distinguishing between market positions for mainstream versus niche brands

How customer and professional critics review valence may influence a focal reviewer is likely to be influenced by a brand’s status as a mainstream or niche brand. Yet, to this point, research in this area has not fully accounted for the distinction between these two types of markets and how OWOM may play out differently in each. In order to address this, we incorporate management research on market dynamics. The distinctions between these types of brands are well established in academic research, with historical traces that are nearly a century old. Indeed, as far back as 1937, leading scholars have been discussing the dynamics of market competition between small and large market share brands. Specifically, Ronald Coase, the preeminent economist and one of the founders of modern management theory (Coase, 1937; Penrose, 2009), posed the deceptively simple question—why, if a brand can gain increasingly powerful efficiencies of scale through larger and larger market share, is there not ultimately just one brand in all mature industries? Resource partitioning theory (Carroll, 1985; Carroll & Swaminathan, 2000) helps to address this natural and longstanding question. The theory posits a positive relationship between the market share growth of mainstream brands and the subsequent emergence of niche market segments on the periphery of a market. Specifically, as an industry matures it tends to develop a large market center that is fiercely contested by a small number of mainstream brands that compete largely based on efficiencies gained from scope and scale economies (i.e., Pepsi vs. Coca-Cola, Target vs. Wal-Mart).

An important byproduct of this process is the emergence of niche market opportunities in the periphery of an industry, which is populated by niche brands that serve customers whose preferences are not being met in the mainstream market. Niche markets, and the niche brands that occupy them, are often predicated on cultural or social movements that spurn mainstream brand counterparts because of a perceived homogeneity and lack of quality in mainstream markets—i.e., oppositional markets (Greve et al., 2006; McKendrick & Hannan, 2014; Verhaal et al., 2015; Weber et al., 2008). Thus, the imageries of market niches are shaped by a shared collective and oppositional identity that stands in sharp contrast to the undifferentiated and general offerings in the mainstream market. Adhering to the underlying oppositional market identity that their customers value allows niche brands to forge a strong, focused brand image that provides differentiation and performance benefits. It also suggests that customer and professional critics review valence may indeed resonate differently across these two market segments.

Lending further credence to the notion that these two distinct markets should be distinguished from one another, research suggests that when mainstream brands do make attempts to capitalize on market niche opportunities, they are not particularly adept at doing so (Hsu et al., 2016; Verhaal et al., 2017). Perhaps these findings should come as little surprise to marketers who are familiar with the difficulty brands typically have in extending their brand image both within and across product categories (Loken & John, 1993; Martinez & De Chernatony, 2004): consumers tend to restrict a brand’s movements to those that align with the established brand image. Yet, while a brand community can build inclusiveness, it can struggle to fully satisfy its members. A consumer’s need for unique offerings, or the tendency to acquire and consume goods that are desirable and unique in order to advance that consumer’s personal and social identity (Snyder, 1992; Tian et al., 2001), has been used to explain why certain consumers may seek out niche brands and how it may be difficult for mainstream brands to successfully fill market niches with product offerings (Abosag et al., 2017; Puzakova & Aggarwal, 2018; Tian et al., 2001).

Related literature on brand community and OWOM

One specific way in which an individual identifies with a brand and brand community is through online reviews. The relationship between a reviewer and a brand can be similar to the relationship between two individuals (Fournier, 1998), and a customer’s balancing act of community involvement and establishing characteristics unique from the community may promote a healthy set of relationship boundaries (Brewer & Pickett, 1999). When consumers perceive their level of uniformity in a brand community to be too high, their need for distinctiveness will likely be triggered. This is akin to the notion of optimal distinctiveness (Barlow et al., 2019; Brewer, 2007; Zhao et al., 2017), or the balancing act between the need to fit in and the simultaneous desire to stand out. Online reviews offer an effective outlet to broadcast these contrasting signals, and create strong connections that resonate not only with firms, but also with the broader online community. There are different ways to broadcast uniqueness such as touting counter-cultural products and championing their affiliation with niche brands (Leonardelli et al., 2010; Tian et al., 2001). Furthermore, the need for uniqueness is known to significantly influence consumer decision processes in a number of contexts (Chan et al., 2012; Simonson & Nowlis, 2000), and may cause a consumer to move away from a mainstream brand offering that is widely adopted and homogenized across the market (Abosag et al., 2017; Puzakova & Aggarwal, 2018). It is posited that such a consumer decision to distance oneself from the mainstream market through niche brand choice can serve to enhance the consumer’s self-image (Dichter, 1966) because niche products provide an opportunity for individuals to express their knowledge about an unfamiliar product with low connection to the general market. This may help to explain why small niche brands hold persistent market positions, despite the fact that high share brands possess both large customer bases and excess behavioral loyalty rates (Ehrenberg et al., 1990).

To continue our effort to integrate perspectives on niche and mainstream brands with online word of mouth, we now turn to detailing the extant literature on individual reviewer rating. Li and Hitt (2008) determined that early product adopters can influence attitudes and purchase intentions of the broader consumer base through online product review ratings. In related research, Godes and Silva (2012) found that more established products receive higher ratings overall, while early product adopters generally provide higher ratings. Most of the extant research in this area has focused primarily on the role of online community (e.g., Ho et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2015; Moon et al., 2010) and reviewer characteristics (e.g., Moe & Schweidel, 2012; Moon et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2018) in driving individual reviewer level valence. Overall, these studies find a positive (negative) impact of valence (standard deviation) of prior community reviews (Godes & Mayzlin, 2009; Gopinath et al., 2014; Luo, 2009; Moon et al., 2010).

Similarly, the findings for the volume of customer reviews are predominantly positive. For example, Sunder et al. (2019) find a positive role for volume in driving individual reviewer valence. In the context of Amazon reviews, Forman et al. (2008) find that an increase in review volume increases the likelihood of a reviewer to disclose her identity. However, Moon et al. (2010) find a negative impact of volume on the valence of movie reviewers. Researchers have also studied the impact of reviewer characteristics. Moe and Schweidel (2012) find that less frequent reviewers exhibit bandwagon behavior whereas more frequent reviewers exhibit differentiation behavior. Other researchers (e.g., Lee et al., 2015; Moon et al., 2010; Sunder et al., 2019) have found results that indicate a positive impact of category experience. Table 1 compiles and compares these related articles on individual rating influencing processes to our study.

Hypotheses development

Overview of conceptual framework

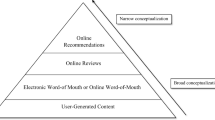

Broadly speaking, our conceptual framework (Fig. 1) seeks to identify divergent theoretical explanations for individual reviewer ratings of mainstream vs. niche brands. Specifically, we suggest that customer review valence is a stronger predictor of individual reviewer ratings than professional critics review valence, and that this dynamic is amplified in niche markets. Moreover, we offer and develop key constructs that might moderate this relationship in an attempt to better understand how niche markets may systematically differ from mainstream markets in terms of reviewer sentiment. Below, we go on to develop the theoretical logic underpinning this conceptual framework.

The roles of customer review valence and professional critics review valence

Previous research has established the positive independent links between both customer review valence (Dhar & Chang, 2009; Duan et al., 2008; Godes & Mayzlin, 2009; Gopinath et al., 2014; Luo, 2009) and professional critics review valence (Basuroy et al., 2006; Chakravarty et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2012; Tsao, 2014) and consumer perceptions/behaviors towards brands/products. Yet, the relative level of influence among these two key OWOM influencers is less clear. In our research, we seek to untangle these relationships further by connecting existing perspectives and provide greater nuance to these relationships.

In a general sense, the Elaboration Likelihood Model (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986) posits that an individual’s tendency to be influenced by external information depends on the degree to which the information is relevant. Aspects of the message and the source of the message are likely to play important roles. One could posit that professional critics could be more influential due to their higher levels of perceived expertise and knowledge in judging and rating products. Yet, due to homophily (Rogers, 1983), or the “like me principle” (Laumann, 1966), a reviewer’s rating could instead be more influenced by the opinions of amateur reviewers than those outside their peer group (professional critics). The reviewer’s shared characteristics with other reviewers in the community may favor communications within the group (Frenzen & Nakamoto, 1993; Granovetter, 1973; Reingen et al., 1984; Susarla et al., 2012) and this effect is likely amplified in environments (like niche markets) where consumers share a common identity.

Additionally, because niche brands have lower overall brand awareness, the spread of positively valenced OWOM content about them has a greater potential to influence the typical market consumer. Our arguments build on those advanced in the corollary literature on long tail online retailing strategy that argues (Anderson, 2006) and empirically shows (Brynjolfsson et al., 2011; Choi & Bell, 2011) that increased information flows and reduced search costs from the Internet enables consumers to more easily learn about relatively obscure brand offerings (such as those in niche market segments). We further this line of reasoning by arguing that this should also hold (or even be amplified) in an OWOM context, given the seemingly exponential proliferation of Internet and mobile search activity among consumers in nearly all market settings (Lamberton & Stephen, 2016).

Ultimately, the valence of customer and professional critics reviews can serve as a tool for the diffusion of positive sentiment, in particular for niche brands that lack alternative means to communicate these signals. In our research, customer review valence is the average rating of all prior reviews of the product whereas professional critics valence is the number of medals awarded by professional critics at the major competition in the beer industry. And we expect the positive sentiment among prior consumer reviews and/or among professional critical reviews to have a greater influence on niche than on mainstream brands as niche brands trigger a reviewer’s need for uniqueness, have lower brand awareness and less formulated brand imagery overall, and leave more room for community and professional opinions to shape the consumer’s brand perceptions. This expectation is also supported by a recent finding by Shi et al. (2020) where, in a study of YouTube videos, they show that OWOM matters more for niche than mainstream products in driving movie box-office performance. Their rationale was that reviewers could more intensively discuss their unique expertise or enhance their identification with the product in the case of a niche product. This means that the quality of information spread through community and professional critics reviews about niche brands is also likely to be higher than that of mainstream brands, making it more influential in nature. An important distinction between this prior work and the current study is that Shi et al. (2020) investigated community feedback on the product’s advertising content, whereas our study instead focuses on an individual’s perceptions of the core product.

This leads to the following set of hypotheses on customer and professional critics review valence, and their relative weight for niche versus mainstream brands.

H1:

The positive influence of customer review valence on an individual reviewer’s rating is stronger than the positive influence of professional critics review valence.

H2:

The positive influences of customer and professional critics review valence on an individual reviewer’s rating are stronger for niche brands than for mainstream brands.

Niche brand localness as an authenticity signal and the role of consumer–brand location similarity

Whereas mainstream brand consumers typically look for large-scale popularity and mass appeal indicators that cut across geographies and even span global reach, niche brand consumers place value on a more authentic connection with the brand and its community of consumers (Beverland, 2005; Warren et al., 2019). Indeed, recent empirical studies have borne out this prediction in a wide variety of market contexts, including television advertising (Becker et al., 2019), craft beer (Carroll & Swaminathan, 2000; Frake, 2017), food trucks (Schifeling & Demetre, 2021), and grass-fed meat (Weber et al., 2008). We extend this logic to argue that an offline locational match between the reviewer and the niche brand will lead to a higher review rating. No such relationship is expected for mainstream brands. This is important because while many mainstream brands prefer to project a global identity in their brand positioning strategies (Steenkamp et al., 2003; Warren et al., 2019), other mainstream brands do try to leverage a local identity. Take, for example, Coors beer, which prominently touts a deep and enduring connection to Colorado and the Rocky Mountains, despite its globally spanning production, distribution, and sales activities.

Consumer–brand location similarity serves as a simple heuristic to aid consumers in their judgments (Becker et al., 2019; Beverland, 2005; Hoskins et al., 2021). Such similarity increases the strength of the reviewer’s relationship with the brand, enhancing the reviewer’s identification with the brand. Reviewers who identify themselves as belonging to a brand and its community report higher rates of brand affect (Marzocchi et al., 2013), brand trust (Matzler et al., 2011) and have a higher loyalty rate (Scarpi, 2010). Strengthened consumer–brand relationships produce resistance against negative information spread about the brand as well (Chang et al., 2013). Such brand affinity is so powerful that reviewers can develop a deep confidence toward the brand and discredit all other sources of information but their own knowledge (Campbell & Keller, 2003). For mainstream brands, however, brand location similarity should not have a similar effect, as the claim of “localness” potentially rings hollow to these consumers and may actually be perceived as inauthentic. Moreover, we expect the focal reviewer of a local brand would be less influenced overall by other external (i.e., customer review valence or professional critics review valence) information sources when evaluating a product with an online review.

H3a:

An individual reviewer’s brand location similarity will positively influence the rating for niche brands, but will have no effect for mainstream brands.

H3b:

The individual reviewer’s rating of a local brand will be less influenced than the typical reviewer by customer review valence and professional critics review valence.

The moderating role of community characteristics

While, to this point, we have theorized a general tilt towards the importance of customer review valence relative to professional critics review valence, there may be certain situations in which the voices of professionals hold more influential weight. There also may be circumstances in which the influence of customer review valence is particularly exaggerated. For example, Wu et al. (2020) find that online community members with more established expertise are more influential than the typical consumer review. Yazdani et al. (2018) also empirically show that experienced reviewers can be a stabilizing force that help consumers make sense of either new products or established, yet controversial, products.

Although no research to our knowledge has tested the role of experienced reviewers in the community against professional critics counterparts, we logically deduce that a growing influential role of customer review valence when reviewers are highly experienced likely means a simultaneous diminishing role of professional critics review valence. We argue this for two reasons. As the growth of online communities/review sites has given the average consumer access to a greater wealth of product information (Armstrong & Hagel, 2000), the aggregated perspectives of the online community have increasingly rivaled, or even superseded, the influential weight of professional critics’ opinions (Tsao, 2014). Prior to the growth and popularity of these sites, however, it was much more difficult for consumers to pool their unique perspectives into aggregate evaluations (Dellarocas, 2003). Second, as community reviewers gain greater expertise and experience in their own right, they may begin to serve as a proxy for, or even to replace, the voice of expert reviewers in the eyes of the typical market consumer (Ketelaar et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2015; Sunder et al., 2019). We argue that this is, in fact, likely because highly experienced community members may have tastes and preferences that are more in line with average or modal consumers, as opposed to the refined tastes and preferences of professional critics (Chakravarty et al., 2010; Tsao, 2014). Anecdotally, this appears to be the case on review websites such as TripAdvisor, where the most highly rated restaurants in a given city are rarely the most critically acclaimed. In our research, we capture the level of experience in the community with the measure community expertise, which is defined as the percentage of prior reviewers who have reviewed at least 200 products in the past. Experienced community members may effectively straddle the line of holding esteem for their category expertise like professional critics do, while also being more similar to the community of consumers than critics ever could be.

Moreover, the online community is known to be more influential when there are tangible shared traits (above and beyond subjective tastes and preferences) between the focal reviewer and the rest of the community (Posey et al., 2010). Such shared traits can simply be perceived by the consumer (Pentina et al., 2018; Stokburger-Sauer, 2010) or can be centered on measurable factors such as gender (Abubakar et al., 2016) or network overlap (Sun et al., 2017). One such known powerful overlap between consumers that can strengthen bonds and increase the influential power of the community is that of community–reviewer location similarity (Forman et al., 2008). Due to in-group/out-group deductions, people tend to trust and agree with those from similar geographic regions to themselves on a surprisingly wide range of factors, which includes brand/product preferences and evaluations (Gillooly et al., 2020; Han & Nam, 2019; Park & Lee, 2015). In our research, community–reviewer location similarity is operationalized as the proportion of prior reviewers who are from the same geographical location as that of the focal reviewer. We build on above prior empirical findings to argue that a matching geographic location between the focal reviewer and the online community will lead that reviewer to be more influenced by the valence of customer reviews from the community and, as a result, less influenced by professional critics.

H4a:

Community expertise enhances (diminishes) the relationship between customer (professional critics) review valence and individual reviewer rating.

H4b:

Community location similarity enhances (diminishes) the relationship between customer (professional critics) review valence and individual reviewer rating.

Each of these baseline predictions, that community expertise and community-reviewer location similarity will alter the influential weight of customer (versus professional critics) review valence, is expected to have a differential impact on niche and mainstream brands. As discussed earlier, the reviewers of niche products are more engaged and are more willing to deeply discuss their unique product experiences and their specific product knowledge (Carsana & Jolibert, 2017; Halkias, 2015). Sharing the same motivation among members of the niche community also creates a strong tie between the focal reviewer and other reviewers of niche products (Beverland, 2005; Thompson & Arsel, 2004). Community tie strength leads to higher influence of within-group members and less influence of outside-group individuals; e.g., Godes and Mayzlin (2009) show that a message sent by a loyal customer to the members of his or her social circle is more persuasive than information spread by the less-loyal group of customers. Thus, we expect niche brand reviewers to be more positively influenced by similar individuals (like the reviewers with community expertise or those from the same geographic location) than reviewers for mainstream brands. Similarly, niche brand reviewers are likely to discredit out-group members (such as professional critics) more than mainstream brand reviewers.

These community characteristics are particularly relevant in our industry context. Many niche brands are located in craft markets, otherwise known as cultural production markets, where a shared understanding or collective identity coheres around local communities and local products (Schifeling & Demetre, 2021). Thus, niche brands reinforce the link between the focal reviewer and community/locational ties. The location similarity between the reviewer and the community can increase the within group similarities, leading to a stronger within-group tie (like other reviewers in the community) and more differentiation with out-group members (like critics). Moreover, given the specificity of niche brands, a focal reviewer may especially rely on the community and not professional critics when expertise among its base of consumers is established and recognized. Altogether:

H4c:

In terms of influencing an individual reviewer’s rating, the moderating effect of community expertise on the impact of customer (professional critics) review valence is more positive (negative) for niche brands than for mainstream brands.

H4d:

In terms of influencing an individual reviewer’s rating, the moderating effect of a reviewer’s community location similarity on the impact of customer (professional critics) review valence is more positive (negative) for niche brands than for mainstream brands.

The moderating role of reviewer characteristics

Reviewer-specific characteristics also have the potential to impact the influencing roles of the customer and professional critics review valence. Category experience, in particular, may lead a focal reviewer to become more cognizant of distinct attributes and details about products and brands within the category (Moon et al., 2010). We define reviewer category experience as the number of prior reviews by the focal reviewer. It has been shown across multiple studies that as a reviewer gains product category experience, he or she is less likely to produce ratings that align with those of the community (Chakravarty et al., 2010; Lee et al., 2015; Moe & Schweidel, 2012; Sunder et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020). These findings are perhaps surprising if one believes that community sentiment should be a relatively efficient marketplace of opinions averaging out extreme positive and extreme negative tails to formulate a relatively accurate average rating for a particular brand or product. However, the extant literature provides an intriguing explanation for this counterintuitive finding: consumers who become more experienced view themselves as category experts who are more knowledgeable than the typical consumer about the marketplace (Ketelaar et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2015; Sunder et al., 2019). This is the point where experienced reviewers are dissimilar with other reviewers, even though they are in the same community, and share more similarities with critics who are outside their group (Chakravarty et al., 2010). Hence, we extend the logic of homophily theory or the “like me” principle to argue that reviewers will tend to align their ratings more with professional critics and less with the general community of consumers as they gain more product category experience..Footnote 2

In addition to category experience, reviewers vary in the degree to which they are engaged in the online forum (i.e., the extent to which a reviewer posts to message boards to interact with other reviewers). It is important to note that highly engaged reviewers can have low category experience and vice versa. Individuals within the community who post regularly and interact with members of the online community tend to be more receptive to the established views of the community (Chan et al., 2015). We extend this viewpoint to argue that these individuals are likely to be less receptive to professional critics reviews in the process. In addition, engagement in communicating with group members because of their similarities can be moderated by different factors, such as the level of time and resources invested (Ruef et al., 2003). Highly engaged reviewers may be more motivated to maintain community ties by listening more to other reviewers and differentiating themselves from outside members like professional critics.

H5a:

Reviewer category expertise diminishes (enhances) the relationship between customer (professional critics) review valence and individual reviewer rating.

H5b:

Reviewer community engagement enhances (diminishes) the relationship between customer (professional critics) review valence and individual reviewer rating.

It has previously been established in the literature that more experienced consumers within a product category are more likely to grow to appreciate niche brands over time (Thompson & Arsel, 2004), which require greater category knowledge to understand (Halkias, 2015; Warren et al., 2019). Reviewers of niche brands can share more unique product knowledge as they gain more category experience, which will also help them in fulfilling their need for differentiation (Tian et al., 2001). Thus, experienced reviewers of niche brands have more unique expertise and knowledge about the product than other reviewers (Carsana & Jolibert, 2017), and as a result they have a higher motivation to fulfill their need of uniqueness (Abosag et al., 2017). In addition, these experienced niche brand reviewers likely share more similar traits with professional critics than other community reviewers (Ketelaar et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2015; Sunder et al., 2019). Consequently, experienced reviewers are likely to be more positively influenced by critics in the case of niche brands relative to mainstream brands. And similarly, we expect reviewers with greater category experience to be more negatively impacted by other reviewers in the case of niche brands than mainstream brands due to the higher differentiation motivation of reviewers for niche brands.

Lastly, as niche brands rely so heavily on shared and collective identities between brands and their communities of consumers (Fritz et al., 2017; Moulard et al., 2016), we also argue that the tendency of a focal reviewer to engage with the community, for example through message boards, will also further strengthen community influence in the case of niche brands. The rationale is that reviewers of niche brands are more motivated than reviewers of mainstream brands to maintain the identity of their community because it becomes easier for them to differentiate themselves from outside-group members (Mathias et al., 2018; Puzakova & Aggarwal, 2018; Verhaal & Dobrev, 2020). Hence, we expect the moderating effect of reviewer engagement with the community to be stronger for niche brands than for mainstream brands.

H5c:

In terms of influencing an individual reviewer’s rating, the moderating influence of a reviewer’s category experience on the impact of customer (professional critics) review valence is more negative (positive) for niche brands than for mainstream brands.

H5d:

In terms of influencing an individual reviewer’s rating, the moderating influence of a reviewer’s community engagement on the impact of customer (professional critics) review valence is more positive (negative) for niche brands than for mainstream brands.

Description of data and variables

Our dataset spans from 2008 to 2011 and includes all review information from the major site for the beer product category: www.beeradvocate.com. This category is divided into large mainstream brands and small niche brands (Carroll & Swaminathan, 2000; Verhaal et al., 2017). According to the guidelines of the Brewer’s Association (BA),Footnote 3 the key distinction between the two is that a niche beer brand must be small, independent and traditional. In other words, it must: produce less than 6 million barrels of beer yearly, have no more than 25% outside ownership, observe industry standards with respect to ingredient quality and tradition. Breweries that mass produce (6 million+ barrels per year) are considered mainstream brands. Our analysis sample is restricted to include only reviewers that joined the site during this observation period. In total, we retain 470,848 reviews by 7552 unique reviewers. Reviews are observed on 14,356 products marketed by 1380 brands, and 102 product styles are represented in the data.

Table 2 gives the variable definitions along with their descriptions and key summary statistics. Tables 3 and 4 show the product specific details of the top 5 highest rated and lowest rated beers.

Dependent variable

The key dependent variable of interest is an individual reviewer’s rating for a product (RATING).

Main independent variables

Consumers derive considerable learning from ratings of other community reviewers and professional critics. We capture these influences with CUSTOMER REVIEW VALENCE (average valence of all prior customer reviews for the product) and PROFESSIONAL CRITICS REVIEW VALENCE (number of medals awarded to the product by professional critics at the major industry competition: The Great American Beer Festival).

To understand the role of location similarity between the reviewer and the product we include a measure, BRAND LOCATION SIMILARITY, which is a dummy variable indicating a location match between the reviewer and the brewery producing the product (beer). To investigate the moderating role of online community in the rating generation process, we include two measures in our analysis. COMMUNITY EXPERTISE is the percentage of prior reviewers who are experienced. We define an experienced reviewer as someone who has reviewed at least 200 products. COMMUNITY LOCATION SIMILARITY is the proportion of prior reviewers of the product who are from the same geographic location as that of the focal reviewer. In addition, to study the role of reviewer-specific factors we include two key variables. REVIEWER CATEGORY EXPERIENCE is the number of prior reviews posted by the reviewer at the time of the current review. There is considerable variation in the category experience levels across reviewers. This is illustrated in Fig. 2 which shows the distribution of the number of reviews by each reviewer in our dataset. REVIEWER COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT is the number of posts made by the reviewer to the online community message boards. These posts are distinct from review activity in that they are socially oriented towards connecting with the community, rather than providing a product specific review.

Control variables

Our empirical analysis also controls for other important factors that can influence an individual reviewer’s rating. We have two community level controls. CUSTOMER REVIEW VOLUME is the volume of prior reviews for the product. CUSTOMER REVIEW DISPERSION is the variance of the ratings of prior reviewers. Extant literature has found a significant relationship between these two measures and the rating of a focal reviewer. To control for the type of medals awarded by professional critics we include % GOLD MEDALS, which is the percentage of total medals awarded by critics that are gold medals. Following Chen and Lurie (2013), we also control for TIME SINCE LAST REVIEW, which is a reviewer level variable that measures the number of days since the last review by the focal reviewer.

Reviewer-specific factors

We include reviewer-specific effects to account for any unique unobservable characteristics of our 7552 distinct reviewers within our data. Controlling for specific fixed effects is a common approach that has been taken in OWOM studies regularly (Chintagunta et al., 2010; Duan et al., 2008).

Product style–specific factors

Product styles are identified by the managing editors of the beeradvocate.com website and are particularly exhaustive sub-classifications. The site identifies two main product styles: ales and lagers. These two general product styles are first broken down based on country-of-origin for the style (e.g., German versus Japanese) and then into specific styles based on texture, alcohol content, and ingredients of the product. That being said, the site notes that these styles are non-official classifications that only attempt to broadly group the significant number of products available in this category. Some products may truly be a combination of two or more basic product styles. The site managers note that the current product style classifications may be debatable among industry experts. As an example, one such style described by the site is that of the “American Black Ale”; the website currently describes the American Black Ale as follows: “Also referred to as a Black IPA (India Pale Ale) or Cascadian Dark Ale, ales of this style range from dark brown to pitch black and showcase malty and light to moderate roasty notes and are often quite hoppy generally with the use of American hops. Alcohol can range from average to high depending on if the brewery is going for a double / imperial version.”

In our econometric model, we include product style specific effects to account for the unique idiosyncrasies of all 102 product styles present in our data. In addition, similar to Chintagunta et al. (2010), we also include all available interactions between product style dummies and reviewer-specific effects to control for unobserved factors that influence the fit of tastes and preferences between reviewers and the different product styles.

Review timing factors

The data include an exact time stamp for each review, which allows us to account for several time-based effects. We include time dummies for quarters (Q1 = January–March, Q2 = April–June, Q3 = July–September, Q4 = October–December) and years (2008, 2009, 2010, 2011) to control for potential seasonality and category evolutionary effects (Gopinath et al., 2014). We also follow prior empirical precedent (Trusov et al., 2009) and control for day of the week (MON-SUN) and time of day (MORNING = 12 AM - 8 AM, MIDDAY = 8 AM – 4 PM, EVENING = 4 PM – 12 AM) effects.

Empirical analysis

In this section, we formulate our econometric model to investigate the role of customer and professional critics review valence in influencing the rating of an individual reviewer. The model also allows us to explore the role of other key factors such as brand location similarity, community characteristics, and reviewer characteristics. Our econometric model is specified in such a way that it facilitates understanding variation of the different effects across different products while accommodating for unobservable factors that might be correlated with our key measures of interest.

Each reviewer reports scores on a 1 to 5 scale (increments of 0.25) for five distinct aspects – taste, look, feel, smell, overall. The RATING measure is the average of these five scores.Footnote 4 The unit of analysis is a reviewer (i)-product (j) combination (ij). Some past researchers (e.g., Wu & Huberman, 2008) have used ordered models because their valence measure included whole integer values that more closely approximated a discrete than a continuous process. However, our rating measure is much closer to a continuous variable because of its sub-rating increments of 0.25 that are then averaged to achieve even more finite increments.Footnote 5 The model is estimated in Log-Log form because the dependent variable and the right-hand side continuous measures have skewed underlying distributions; binary variables are not logged. The model, which estimates the rating given by reviewer i for product j, is specified as:

Where:

In Eq. (1), αi denotes the reviewer fixed effect; δj denotes the product fixed effect. We also include dummy variables for time of day, day of week, the season, and the year in which the review was written. εij is the reviewer–product unobservable. In addition to reviewer-specific factors and product-specific factors, there could be reviewer-product–specific factors that could result in the error term εij being correlated across products. For example, the reviewer may review certain products because of unobserved (to the researcher) expertise or interest for certain product characteristics. To account for such factors, we include interactions between reviewer fixed effects and product characteristics (product styles). In our model, these interactions are represented by Γ7iPRODUCT STYLEj and account for any inherent match between the reviewer and the product, without which one may erroneously attribute the differential review valence across products to product level response heterogeneity to different factors. In other words, our objective in including these factors is to account for the reviewers’ endogenous reviewing decisions. So, our identifying assumption is that conditional on these variables, there is no error correlation across reviews.

Endogeneity correction

As is common in this area of research, endogeneity can materially impact the reported results of our study, and therefore is an important issue to address (Rutz & Watson, 2019). The potential sources of correlation in Eq. (1) are the correlations between the online community measures and the error term. We do account for this to some extent by including product fixed effects and reviewer–product characteristics interactions. However, time-variant characteristics such as television advertisements or radio play are not removed through fixed effect estimation and may affect both review activity of the online community as well as the focal reviewer in a given period.

Prior studies in this area have used both limited information (e.g., Chintagunta et al., 2010; Gopinath et al., 2013) and full information approaches (e.g., Duan et al., 2008) to deal with this challenge. In this research, we correct for endogeneity in the estimation by using Copulas to jointly estimate the distribution of the endogenous variables and the error term (Park & Gupta, 2012). Copulas is an instrument free approach that has been used recently by several other marketing area researchers for endogeneity correction (Carson & Ghosh, 2019; Datta et al., 2015; Datta et al., 2017; Lenz et al., 2017; Schweidel & Knox, 2013).Footnote 6

Table 5Footnote 7 shows the results in three columns. Column 1 reports the results with all products included, column 2 reports the results for mainstream brands only, and column 3 reports the results for niche brands only. The coefficients across the different columns can be directly compared because they are elasticities as a result of the Log-Log specification. It is lastly important to reiterate that each model specification includes a large number of estimated but unreported terms including reviewer fixed effects, product style fixed effects, product style/reviewer interactions, day of the week effects, and time of the day effects.

The roles of customer and professional critics review valence in influencing the focal reviewer

We first focus on the effects of customer and professional critics review valence. The main variables of interest are the two valence measures: CUSTOMER REVIEW VALENCE and PROFESSIONAL CRITICS REVIEW VALENCE. Γ1 captures their effects. The first key finding is that both the valence of the community and the valence of professional critics have a positive and significant impact on the rating awarded by a new reviewer. Moreover, in support of H1, we find that the impact of customer review valence (0.9425, p < 0.01) is much stronger than the impact of professional critics review valence (0.0201, p < 0.05). The difference is statistically significant at the 1% level. Second, we find that the magnitude of the valence of customer reviews main effect is stronger for niche brands (0.9017, p < 0.01) than for mainstream brands (0.7846, p < 0.01). The difference is statistically significant at the 1% level. Similarly, the impact of professional critics review valence is positive and significant for niche brands (0.0351, p < 0.01) but not for mainstream brands indicating a full mediation effect. Hence, there is support for H2.

Turning to the control factors, additional results emerge. In line with prior research, the customer review volume has a positive and significant effect (0.0015, p < 0.01) on the rating of the focal review. More importantly, this effect is larger for niche brands (0.0025, p < 0.01). This result reveals a full mediation effect as the volume of customer reviews has no significant impact for mainstream brands. The dispersion in reviews from the online community was expected to negatively impact valence of the focal review and the model with all products indeed supports this (−0.0393, p < 0.01). Moreover, this negative effect is significant only for mainstream brands (−0.4645, p < 0.01), suggesting full mediation here as well. In addition, the percentage of gold medals awarded by critics has a positive impact (0.0037, p < 0.01) on individual reviewer rating. This positive impact is statistically significant only for niche brands (0.0034, p < 0.01). We also find that the number of days since the most recent review has a significant negative impact on overall rating for both mainstream brands (−0.0047, p < 0.01) and niche brands (−0.0028, p < 0.01).

Niche brand localness as an authenticity signal and the role of consumer–brand location similarity

In marketing and economics, the concept of location similarity has been studied in scenarios mostly outside of the context of online WOM. For example, Goolsbee and Klenow (2002) showed that the number of new computer buyers in a market was influenced by the proportion of households that already owned a computer in that market. Bronnenberg and Mela (2004) studied the introduction of two new major brands in the frozen pizza category, finding evidence of contagion effects in that a local retailer is more likely to adopt a new product if competing retailers in the region have already adopted the product. However, in the OWOM context, the use of location data has been limited primarily due to the difficulty in obtaining market level OWOM data. To analyze the U.S. movie industry, Gopinath et al. (2013) used location data to study how different geographical markets (DMAs) are influenced by OWOM measures and advertising. However, they did not explore how similarity among markets can impact the overall influence of the different measures. Forman et al. (2008) analyzed Amazon data on books and found that a reviewer is more likely to disclose personal information if the current and previous reviewers share the same location.

To understand the role of brand location similarity in influencing an individual’s review rating we focus on the interactions between BRAND LOCATION SIMILARITY and the two valence measures (CUSTOMER REVIEW VALENCE and PROFESSIONAL CRITICS REVIEW VALENCE). The first key finding is that the location similarity between the brand and the focal consumer has a positive impact on the consumer’s rating (0.0815, p < 0.01). In addition, this effect is fully mediated by niche brand status, as it is only significant for niche brands (0.0951, p < 0.01). This result provides support for H3a. This is because niche brands are committed to local brand positioning strategies unlike mainstream brands that rely on large-scale popularity and mass appeal that cut across geographies (Steenkamp et al., 2003; Warren et al., 2019). Moreover, negative coefficients of the brand location similarity interactions indicate that the reviewers of local brands are less influenced by external information sources such as customer review valence (−0.0473, p < 0.01) and professional critics review valence (−0.0043, p < 0.01). Hence, H3b is supported as well. The explanation is that sharing the location with a brand develops strong customer brand relationships which increases the affinity towards the brand (Chang et al., 2013). As a result, the reviewer has greater trust toward the brand and discounts all other sources of information but their own knowledge.

The moderating role of community characteristics

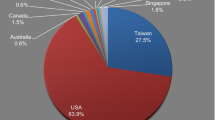

In this section, we focus on how the impact of the valence measures (CUSTOMER REVIEW VALENCE and PROFESSIONAL CRITICS REVIEW VALENCE) are influenced by two key online community characteristics: COMMUNITY EXPERTISE and COMMUNITY LOCATION SIMILARITY. Figure 3 shows the location distribution of the reviewers in the online community.

There are several new insights from Table 5. First, we find that when the prior reviewers are more experienced, the valence of their reviews have a stronger influence (0.0928, p < 0.01) on the focal reviewer’s rating. This is because these reviewers have more established expertise (Wu et al., 2020) and can be a stabilizing force on consumer decisions (Yazdani et al., 2018). In contrast, we find that as the expertise of customer reviewers increase, the positive impact of professional critics review valence decreases (−0.0168, p < 0.01). The rationale is that as customer reviewers gain greater expertise they may begin to serve as a proxy for the voice of professional critics since the value of the information provided by professional critics decreases. These results provide empirical support for H4a.

Second, we find that the moderating effect of community expertise on customer review valence is about 50% stronger for niche brands (0.0975, p < 0.01) when compared to mainstream brands (0.0641, p < 0.01). This difference is statistically significant at the 10% level. The explanation is as follows: Reviewers for niche brands are much more engaged and willing to share their unique product experiences and knowledge. This leads to stronger ties between these reviewers and other reviewers within the niche brand community. Hence, a typical niche brand reviewer is more influenced by within-group experienced reviewers than a mainstream brand reviewer. Similarly, because of increased group tie strength, reviewers of niche brands are more likely to discredit the opinion of outside-group members such as professional critics (−0.0102, p < 0.01). As expected, this interaction effect is not statistically significant for mainstream brands. These results provide empirical support for H4c.

Third, the interaction term between community location similarity and customer review valence is positive (0.0158, p < 0.01), whereas the interaction with professional critics is negative (−0.0015, p < 0.01) This result provides support for H4b. Moreover, we find that the prior review valence interaction effect is positive and significant for niche brands (0.0179, p < 0.01) but not for mainstream brands, whereas the professional critics valence interaction effect is not statistically different between the two brand types. Hence, there is partial support for H4d. An intriguing result that emerges is that niche brand status moderates community expertise’s positive impact (0.1419, p < 0.01) and mediates community location similarity’s positive impact (0.0061, p < 0.01); mere shared community and presence of prior experienced reviewers drives higher review ratings for niche brands, irrespective of the valence of the reviews from the community.

The moderating role of reviewer characteristics

Finally, the results in Table 5 also reveal interesting insights about the moderating role of reviewer characteristics. The two key measures of interest are REVIEWER CATEGORY EXPERIENCE (number of reviews by the focal reviewer) and REVIEWER COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT (number of posts in the community forum by the focal reviewer). The correlation between the two measures is only 0.16, suggesting that the overlap is not too high (i.e., there are reviewers who review products frequently but are not that involved in the online forum and vice versa).

There are several key findings. First, in support of H5a, those reviewers who have more experience in the product category depart from the aggregate perspective of the online community (−0.0631, p < 0.01) and align more with professional critics (0.0003, p < 0.01). This is because consumers who gain more experience in the product category consider themselves as having more category knowledge than typical reviewers in the online community, instead sharing more similarities with professional critics.

In support of H5c, this pattern of experienced reviewers aligning with professional critics is stronger for niche brands (0.0004, p < 0.01); in fact, there is a null result for the mainstream brands. Moreover, the departure from the online community perspective by experienced reviewers is less pronounced for mainstream brands (−0.0518, p < 0.01) than for niche brands (−0.0793, p < 0.01). The difference is statistically significant at the 10% level, even after controlling for the main effect of reviewer category experience which captures the evolving tastes of the reviewers.

By contrast, engaged reviewers who post more frequently to message boards within the online community are found to be more influenced by the valence of reviews from the online community (0.1017, p < 0.01). This effect is somewhat intuitive in nature, as these reviewers are likely more closely engaged with and socially tied to the online community. Moreover, we find that highly engaged reviewers are less affected by professional critics: the interaction effect between reviewer community engagement and professional critics valence is negative (−0.0043, p < 0.01). These results support H5b. The explanation is that reviewers who interact regularly with the community are more receptive to the views of the community (Chan et al., 2015) and consequently are less receptive to outside sources such as professional critics. In addition, there is the empirical support for H5d, that the interaction effects between reviewer community engagement level and the two valence measures (community review valence and professional critics valence) are stronger for niche brands than for mainstream brands. Specifically, the coefficient for the interaction of reviewer engagement with community valence is larger for niche brands (0.2351, p < 0.01) than for mainstream brands (0.1164, p < 0.01). The difference between these two coefficients is statistically significant at the 1% level. Similarly, the coefficient for the interaction of reviewer engagement with professional critics review valence is significant only for niche brands (−0.0053, p < 0.01).

Discussion and conclusion

General discussion

This research investigates how an individual reviewer’s rating for niche brands and mainstream brands may experience different levels of influence from the valence of customer and professional critics reviews due to key underlying distinctions between these two types of brands. Additionally, the degree to which customer and professional critics review valence may influence a focal reviewer’s rating is also dependent on key community characteristics, reviewer characteristics, and the locational similarities between the focal reviewer and the brand, and its online community base, in question. Ultimately, our line of inquiry contributes to both the OWOM literature, which has sought to further understand how context may alter the level of influence that the customer and professional critics review valence may have, and to the literature on niche brands which seeks to understand how they are different from mainstream brands and how managers of these brands should adjust strategy accordingly. Combining these two disparate literatures also yields additional novel synthesized insights.

Our study builds upon a body of research on the influence of OWOM on consumers in the marketplace: while many aggregate-level effects (i.e., customer and professional critics review valence) have been well established already, recent research has begun to disentangle more category, brand, product and individual level factors that may moderate or mediate these general relationships in important ways. Our study contributes directly to this line of inquiry by using established theory on niche and mainstream brands to juxtapose the expected impacts of OWOM on niche brands versus mainstream brands.

There are several key findings from this study that add to our overall understanding of the OWOM domain. Specifically, we find that although both customer review valence and professional critics review valence have a positive impact on the individual reviewer’s rating, the impact of customer review valence is stronger. Moreover, both of these effects are stronger for niche brands than for mainstream brands. Next, the degree of location similarity between the brand and the focal reviewer has a strong positive impact on the reviewer rating. But this effect is significant for only niche brands, which we argue is due to the fact that niche brands often highlight localness as evidence of quality and authenticity. Interestingly, brand location similarity reduces the positive impact of customer review valence and professional critics review valence because of increased brand trust and decreased reliance on other sources of information.

Next, we find evidence of key moderating effects for community characteristics. Specifically, we find that when the community of prior reviewers have greater product expertise, their ratings have a stronger influence on the focal reviewer’s rating. Greater community expertise also decreases the focal reviewer’s reliance on professional critics ratings. These effects are stronger for niche brands because of unique product experiences and stronger group ties within niche brand communities. We find similar effects when there is location similarity between the reviewer and the community of prior reviewers.

Finally, we are able to uncover additional insights on the moderating role of reviewer characteristics. Notably, reviewers with more category experience tend to align their viewpoints more with professional critics than with the rest of the online community: this tendency is particularly strong in the case of niche brands. However, reviewers who are actively engaged in the community by posting in the community forum are more influenced by the OWOM community overall: again, these key results are stronger in the case of niche brands.

Taken together, these findings provide a comprehensive and nuanced look at both the OWOM literature in general, and specifically how the distinction between niche and mainstream brands can help influence our understanding of the key variables that drive individual review level rating with OWOM. Furthermore, the substantive differences found between niche and mainstream brands shows that niche brands are clearly a unique and special case of brands that demand more deep understanding. Niche brands have been previously studied in a variety of industries that include (but are not limited to): automobile manufacturing (Dobrev et al., 2001), daily newspapers (Boone et al., 2002; Carroll, 1985), insurgent micro-radio stations (Greve et al., 2006; Sikavica & Pozner, 2013), organic food (Weber et al., 2008), electricity markets (Liu & Wezel, 2015), technology security and software (Fosfuri et al., 2018), and environmental movements (Soule & King, 2008). However, very few studies have considered how the processes and influences of OWOM may differentially impact niche and mainstream brands. Future work should look to investigate how our findings may extend to other product categories and to identify additional factors that may be distinct about niche brands and how information flows through OWOM activity.

A final key feature of this study is the use of the Copulas methodology, an instrument free endogeneity correction approach, which has generated considerable interest in the marketing literature recently (Carson & Ghosh, 2019; Datta et al., 2015; Datta et al., 2017; Lenz et al., 2017; Schweidel & Knox, 2013). This also builds upon the general growing attention paid in the marketing literature to accounting for endogeneity (Rutz & Watson, 2019). Our methodological approach allows for some generalization of the key findings beyond the beer product category. Specifically, our model has the following key features: product fixed effects (which remove the influence of beer specific time-invariant unobserved factors), reviewer fixed effects (which remove the influence of time-invariant characteristics of beer reviewers), and endogeneity correction using Gaussian copulas (which controls for remaining unobserved time-varying product and reviewer characteristics). The rigorous approach allows a clearer, generalizable understanding of the roles of community valence, professional critics valence, and key moderators after accounting for beer category specific characteristics.

Several key literature contributions emerge from this study. The first key contribution is that this research links the literature that contrasts niche brands to mainstream brands with OWOM research to show that niche brands have considerably more to gain from OWOM information flows than mainstream brands do. As a result, nearly all of the core empirical results are magnified in the case of niche brands. A second major contribution is that a category consumer may build up knowledge and interactions with the category in one of two distinct ways: (1) to become more involved with products and brands and to generate content and/or (2) to become more engaged with members of the online community surrounding the product category. The empirics show these two processes are nearly uncorrelated and have substantially different impacts on reviewer behaviors. Lastly, a key contribution that emerges is that the valence of customer reviews from the online community has a generally stronger influence than professional critics review valence on a focal reviewer’s rating. Online community influence is especially high when the community is high in expertise and/or it shares traits with the focal site user.

Managerial implications

This study also seeks to make key practical managerial contributions. One clear managerial implication from this research is that promoting OWOM appears to be a distinct marketing strategy for niche brands when compared to mainstream brands. While it is relatively straightforward to assume that all brands, large and small, would benefit from positive OWOM activity, a clear roadmap to how brands in different areas of the market (niche vs. mainstream) should go about achieving this is more elusive. As a result, our study suggests that managers should take note that OWOM could likely play an outsized role for niche brands in terms of crafting an effective marketing strategy. Thus, greater attention and resources should be devoted to it in niche markets.

Moreover, for managers of niche brands, while both customer review valence and professional critics review valence play a more important role compared to mainstream markets, the online community’s judgments are particularly influential. This should help gear managers’ marketing attention toward gaining endorsement and buy-in from the community of consumers as opposed to focusing all attention on one specific endorsement from critics or professionals in the industry, assuming that community approval will follow. If anything, the relationship may be the opposite—as community appeal and endorsement coheres around certain brands in niche markets, critics and professionals may begin to take notice of these relatively obscure brands and give them their own subsequent seal of approval. Managers may be well advised to identify community endorsement as the genesis, or catalyst of this virtuous circle for OWOM valence. Gaining endorsement from experienced community reviewers can be particularly impactful.

Additionally, we identify several key moderators that managers should take note of: location similarity, reviewer characteristics, and community characteristics. For example, for those managers of niche brands, particular attention should be paid to creating or (when already present) highlighting a brand location–consumer location match. This includes creating marketing strategies that educate consumers on the localness of their brand, or tying the brand to local traditions, histories, or events because it can engender a sense of authenticity-based appeal when consumers share this same background.

Our empirical results also indicate that managers of online communities should consider targeting testimonials and featured reviews to users based on shared characteristics and traits. As reviewers are shown to be more heavily influenced by the online community when they share traits with that community (geographic location, in the context of our study), one can conclude that an online community that manages to promote the focus on reviews from such a prior reviewer may be more successful in connecting with the focal user. This recommendation should readily generalize past the beer product category as it pertains directly to the role of OWOM influence from peer-to-peer and is not category-specific. Another potential observed user behavior that site managers can leverage in appealing to a focal user is the user’s previous interactions with other members of the online community, as we find that users who engage more frequently with the community become more trusting of that community. Hence, in order to promote the effectiveness of the information flow, a site manager can feature product reviews from other users who the focal user has previous engaged directly with on the site.

Finally, these results are likely to generalize most in repeat repurchase categories like beer, where customer loyalty can be built as a valuable resource base (Watson et al., 2015). We provide in Fig. 4 a classification scheme that reveals the level of customer and professional critics review valence influence observed at a brand specific level. This analysis extension was generated by interacting each brand fixed effect with the customer review valence and professional critics review valence main effect terms. As a result, we are able to classify mainstream and niche brands into one of four groups based on whether they are high (low) in terms of critics influence and high (low) in terms of customer review valence influence. Such an analysis can aid managers in evaluating their social media strategies, and serve as a foundation through which to develop a broader marketing strategy which is built around OWOM in niche markets (it is important to note that these effects capture the indirect impact on sales).

This classification reveals some interesting insights. The major takeaway here is that more than half of mainstream brands (as opposed to less than 5% of niche brands) have low influence from both the online community and professional critics. By contrast, nearly half of the niche brands (as opposed to ~3% of mainstream brands) in our data are heavily influenced by both online community and professional critics. Niche brands in Group D can generate more positive reviews by building a stronger community and/or by focusing on providing a product with strong critics’ appeal. However, brands in Groups B and C have to rely on one of these two levers. Group C brands can invest in strengthening the online community to generate favorable reviews, whereas Group B brands need to rely on developing better strategies to identify what appeals to critics for eliciting positive online reviews. Finally, brands in Group A need to think beyond focusing on critics and nurturing online community to develop appropriate strategies.

Limitations and future research