Abstract

Academics as well as managers have long been interested in the role of satisfaction with complaint handling (SATCOM) in shaping customers’ attitudes and repurchasing decisions. This interest has generated a widespread belief that SATCOM is driven by the perception that the complaint handling process is just. To test how SATCOM is modulated by distributive, interactional, or procedural justice, we performed a meta-analysis of 60 independent studies of the antecedents and consequences of SATCOM. Results indicate that SATCOM is affected most by distributive justice, then by interactional justice, and only weakly by procedural justice. We also find that SATCOM mediates the effects of justice dimensions on word-of-mouth. However, contrary to common belief, SATCOM does not mediate the effects of justice dimensions on overall satisfaction and return intent. We draw on our results to suggest several avenues for further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Experiencing a service failure is a highly probable event for service customers. The 13th U.S. Annual Consumer Complaint Survey (2005) reports that among the top ten activities that generate the most complaints, eight concern services. Although eliminating service failures is very difficult, service marketers can offer customers the opportunity to complain. An effective recovery process can then repair the service failure and, consequently, turn dissatisfied customers into satisfied ones, improving customer relationships and preventing defection (Fornell and Wernerfelt 1987).

The managerial relevance of complaint handling is reflected in 20 years of academic research on satisfaction with complaint handling (SATCOM). Empirical research has investigated several constructs in an attempt to understand the correlates of SATCOM in a variety of industries and cultural settings. Justice theory has emerged as the most frequently investigated framework for understanding what drives satisfaction with complaint handling. Research has adopted a three-dimensional conceptualization of justice, identifying distributive, interactional, and procedural justice as the main antecedents of SATCOM.

Despite a widespread adoption of the justice framework among complaint handling scholars, research findings vary considerably. On the one side, there is variability in the absolute strength of relationships between each justice construct and SATCOM. The correlations among SATCOM and the justice dimensions range from 0.06 to 0.97 for distributive justice, from 0.05 to 0.92 for interactional justice, and from −0.06 to 0.84 for procedural justice. On the other side, there is variability in the relative strength of the effects of each justice dimension on SATCOM. Studies widely disagree as to which justice dimension is the most important antecedent of SATCOM.

Several studies have focused on the consequences of SATCOM, transposing the customer satisfaction framework (Oliver 1997) to complaint handling situations, thereby identifying return intent, word-of-mouth behavior, and overall satisfaction as the three focal outcomes of SATCOM. The satisfaction framework has also served to identify SATCOM as the central mediator that links perceptions of the justice dimensions to postcomplaint outcomes (Tax et al. 1998). Although most research has hypothesized SATCOM to mediate the effects of justice dimensions on outcome variables, tests of its mediating role are rare, and findings have been mixed at best. Therefore, it remains to be proved whether these findings can be generalized across studies.

Because of the managerial and academic importance of complaint handling research, an empirical assessment of SATCOM findings appears worthwhile. Such an assessment can document both the magnitude of effects that can be expected on average, and the variance in the effects that can be ascribed to substantive and methodological choices of researchers. It can also examine whether the mediating role of SATCOM can be generalized across the research stream. We use meta-analysis to empirically assess the results of research findings across several studies. Through the meta-analysis we wish to: (1) assess the strength and the relative importance of the relationships among SATCOM, the justice dimensions, and the focal outcomes, (2) document the extent to which moderator variables affect the variance in these relationships, (3) test the mediating role of SATCOM, and (4) provide guidance for academics by distinguishing settled issues from topics that still require attention.

Conceptual framework

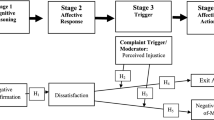

The structure guiding our conceptual discussion and empirical analysis is grounded in the perceived justice framework which represents the prevailing model in complaint behavior research. Figure 1 illustrates the constructs that the majority of conceptual and empirical evidence considers in relation to SATCOM.

Satisfaction with complaint handling

SATCOM is the customer’s evaluation of how well a service company has handled a problem. The literature is rich in synonyms for this concept: service recovery satisfaction (Boshoff 1997), satisfaction with service recovery (Maxham and Netemeyer 2002), overall complaint satisfaction (Stauss 2002), and satisfaction with the remedy (Harris et al. 2006) exemplify the latitude of terms employed in the literature. Despite these linguistic differences, the general framework behind these definitions is the confirmation / disconfirmation paradigm of the satisfaction literature (Oliver 1980). Customers compare their perceptions of the actual performance of the complaint handling procedures with their expectations towards that performance.

Antecedents of SATCOM

On the antecedents’ side, research on complaint handling has focused predominantly on modeling the effects of the dimensions of perceived justice on SATCOM. The concept of justice finds its roots in social psychology. It has proved valuable to explain individuals’ evaluations of the “rightness” of exchanges as well as individual reactions to different conflict situations. In marketing, the justice framework has served to explain customers’ perception of fairness of the service encounter (Clemmer and Schneider 1996) and customer reactions to service failure/recovery encounters. Research across several contexts has identified three dimensions of perceived justice: distributive, procedural, and interactional.

Distributive justice

Distributive justice occurs whenever an individual involved in an exchange relationship feels that the expectation of a gain that is proportional to the investment is met (Homans 1961). In a complaint handling context, distributive justice centers on the perceived fairness of the redress offered to the customer to resolve the complaint (Blodgett et al. 1997). Redress includes refunds, exchanges, repairs, discounts on future purchases, or some combination of these (Blodgett et al. 1997). A positive relationship between distributive justice and SATCOM is supported in past studies: complainants who perceive the redress offered by the service company as fair are satisfied with how the complaint handling process was handled by the firm.

Procedural justice

Procedural justice can be defined as the perceived fairness of the means (i.e., policies, procedures, and criteria) used by decision makers in arriving at a dispute resolution (Lind and Tyler 1988). In complaint research, procedural justice includes elements such as accessibility (i.e., the ease of engaging in the complaint process), time required to complete the process, flexibility of the procedures to meet individual needs (Tax et al. 1998; Smith et al. 1999), and the clearness, readability, and customer orientation of the procedures (Severt 2002). In general, procedural justice and SATCOM are positively correlated, although the magnitude and significance of the effects vary considerably across studies.

Interactional justice

The quality of the interpersonal treatment people receive when procedures are implemented is referred to as interactional justice (Colquitt et al. 2001). The inclusion of this dimension helps to explain why some people might feel unfairly treated even though they would evaluate the redress and the procedures as fair (Tax et al. 1998). In a consumer complaint context, the empathy, politeness, effort, and honesty of the employees have been recognized as associated with interactional justice. Not surprisingly, customers experiencing fair interpersonal treatment express satisfaction with the way the complaint was handled. The positive relationship between interactional justice and SATCOM is supported across studies.

The relative importance of the distributive, procedural, and interactional justice

Past research exhibits considerable difference in the relative strength of the effects of each justice dimension on SATCOM. Among the studies that consider the joint effects of all three justice dimensions, the majority (61%) identifies distributive justice as the most strongly related to SATCOM (e.g., Homburg and Fürst 2005; Smith et al. 1999). These studies are equally divided into experimental and field studies, but they rely almost exclusively on samples of real customers. Thirty per cent of the studies indicate that interactional justice is stronger (e.g., Tax et al. 1998; Smith and Bolton 2002). These studies are mainly experiments, use primarily samples of real customers, and are conducted, for the most part, in the hospitality industry. Finally, the proportion of studies that finds procedural justice as the most related to SATCOM is small (9%), but very homogeneous in its characteristics: these studies are all survey-based, and use all customers samples (e.g. Maxham and Netemeyer 2003).

Evidence of the variability both in the absolute and in the relative strength of the effects of each justice dimension on SATCOM calls for an understanding of the potential sources of this variation, and a meta-analytic assessment of the strength of these relationships.

Consequences of SATCOM

On the consequences side, research on complaint handling has focused on a few outcomes of SATCOM. These outcomes, which are mainly drawn on the customer satisfaction literature (Szymanski and Henard 2001; Oliver 1997) are: intent to return as a customer, word of mouth behavior, and overall satisfaction.

Return intent

Return intent is typically treated as an indicator of attitudinal loyalty (Lam et al. 2004), and is defined as the likelihood of making future purchases from a specific retailer—in this context, from the service provider involved in the failure/recovery scenario (Holloway et al. 2005). Return intent is extremely important after service failure has occurred, because complainants who feel satisfied with the way the company has handled their problem are likely to repurchase from that specific company (Spreng et al. 1995; Maxham 2001). The positive relationship between SATCOM and return intent is consistent across studies.

Word of mouth

Word of mouth (WOM) behavior consists of providing potential customers with information about a company. In a service recovery context, firms may restore customers’ propensity to spread positive communications by ensuring satisfactory problem handling (Maxham 2001). Research has widely documented the existence of a positive relationship between SATCOM and positive WOM: if a firm handles complaints effectively, this not only tends to reduce the occurrence of negative word of mouth, but also increases the likelihood that customers will recommend the service to friends, relatives, and significant others (Blodgett et al. 1993, 1997; Davidow 2000; Maxham 2001). These findings have been fairly consistent across studies.

Overall satisfaction

Overall satisfaction after the complaint has been defined as the degree to which the complainant perceives the company’s general performance in a business as meeting or exceeding expectations (Maxham and Netemeyer 2003). Overall satisfaction is a long-term consequence of SATCOM, and is cumulative in nature, whereas SATCOM itself is a transaction-specific form of satisfaction (Homburg and Fürst 2005). In general, SATCOM is positively associated with overall satisfaction: being satisfied with the complaint handling process increases the “stock” of overall satisfaction towards the firm. Despite the positive sign of the relationship, the magnitude of the effects has varied across studies.

Mediational role of SATCOM

The meta-analytic framework proposed in Fig. 1 postulates that the effect of justice constructs on return intent, WOM, and overall satisfaction are indirect via their effects on SATCOM. This view is consistent with the prevailing complaint handling research, where SATCOM is conceptualized as the central mediator that links justice dimensions to postcomplaint constructs (e.g., Homburg and Fürst 2005; Tax et al. 1998; Ambrose et al. 2007). However, research has not always explicitly examined mediation. Some studies have not included SATCOM outcomes in their models, implicitly considering SATCOM as the driver of return intent, WOM, and overall satisfaction (e.g., Smith et al. 1999). Other studies implicitly hypothesize mediation of SATCOM between justice dimensions and outcome variables without testing for mediation (e.g., Homburg and Fürst 2005; Tax et al. 1998). Only a small number of works formally investigates mediation (Maxham and Netemeyer 2002; Liao 2007; Ambrose et al. 2007). As the central role of SATCOM has often been noted in complaint handling research, we posit that the effects of the justice dimensions on WOM, return intent, and overall satisfaction are mediated by SATCOM. Thus:

-

H1a: The effects of the justice dimensions on WOM are mediated by SATCOM

-

H1b: The effects of the justice dimensions on overall satisfaction are mediated by SATCOM

-

H1c: The effects of the justice dimensions on return intent are mediated by SATCOM

Potential moderators

We identified five potential moderators of the relationship between SATCOM and its correlates. These study characteristics are methodological approach, participants, number of industries, the SATCOM measure, and culture.

Methodological approach

This moderator indicates whether researchers used experimentally-generated scenarios or surveys. Smith et al. (1999) underline the advantages of using experimental scenarios in the context of service recovery, as their use reduces biases from memory lapses and allows controlling for alternative accounts. On the other hand, scenarios compromise realism and place the customer in a hypothetical situation. Surveys do not permit to eliminate potential confounds by randomly assigning subjects to the experimental conditions, but they are typically more realistic because they place the customer in a natural consumption situation. Since experimentally generated scenarios permit tighter control on potential confounds, they might be expected to elicit larger effects sizes than field studies (Farley et al. 1995).

Participants

Studies also diverge in the use of student versus non-student samples. Students are atypical consumers and may have somewhat different attribute importance weights than other customer segments for services (Smith and Bolton 2002). These differences could derive from socio-demographic characteristics, from students’ more limited consumption experiences, or from a different cognitive structure (Szymanski and Henard 2001; Park and Lessig 1977). Burnett and Dunne (1986) found significant differences in the mean scores, factor structures, and correlation coefficients of several marketing constructs among students, their parents, panel members, and comparably aged non-students. On these bases, we test for a difference in effect sizes between the types of participant used in the study.

Number of industries

Some studies draw their sample from one particular industry (e.g., Smith et al. 1999), whereas some others draw samples from multiple industries (e. g., Tax et al. 1998). Research using samples drawn from multi-industry generates more variability in the data, which in turn should result in a higher magnitude of correlation coefficients (Geyskens et al. 1998).

Measurement level

Studies differ in the number of items used to capture the construct of SATCOM. Some studies use a single-item measure whereas others use a multi-item measure. Multi-item measures are supposed to generate higher effect sizes because they tap into the construct domain more completely than a single-item measure (Brown and Peterson 1993). It is also possible, however, that a single-item measure might be a more accurate measure of customer satisfaction, as it allows the incorporation of the factors that consumers would naturally consider in their judgment (Szymanski and Henard 2001). Thus, the analysis of how the measurement level explains differences in SATCOM effects is necessarily exploratory.

Culture

Some research has highlighted that cultural differences could affect the strength of the relationships across the antecedents of SATCOM. Within these works, Hofstede’s (1997) dimensions of culture, i.e., individualism–collectivism, uncertainty avoidance, power distance and masculinity–femininity are the most widely used in international marketing studies (Soares et al. 2007). Since the effects of the three justice constructs do not hold equally across cultures, we formulate predictions on how cultural dimensions may affect the relationships between each justice construct and SATCOM.

Individualism–collectivism describes the relationships between the individual and the group in each culture. In individualistic societies the ties between individuals are loose, and individuals look after themselves, whereas in collectivist societies people belong to groups which protect them in exchange for loyalty (Hofstede 1997). Individualistic societies tend to focus on individual gains, emphasizing personal achievements in job or private wealth. Mattila and Patterson (2004) found that discount and apology restored more effectively the perception of justice in America (an individualistic society) rather than in Thai and Malaysia (a collectivistic society), suggesting that the compensation, and the specific behavior of the contact personnel that has recovered the service failure is more valued in individualistic than in collectivistic societies. Thus, for the distributive justice→SATCOM relationship, and for the interactional justice→SATCOM relationships we expect effect sizes to be higher (lower) for individualistic (collectivistic) cultures.

Individualistic societies are less susceptible to social influence, whereas collectivistic societies value group harmony and emphasize the interdependence of collective groups. As such, they are cooperative and responsive to norms. Therefore, collectivistic societies should appreciate more the policies and the procedures that the organization has established to restore satisfaction after a service failure. Thus, we expect effect sizes to be lower (higher) for individualistic (collectivistic) cultures for the procedural justice→SATCOM relationship.

Power Distance refers to the extent to which the less powerful members of organizations and institutions accept and expect that power is distributed unequally (Hofstede 1997). Cultures scoring high on power distance value obedience and authority, and display tolerance for the lack of autonomy. As a result of their tolerance, in high power distance cultures, customers’ expectations of a symmetric relationship will be comparatively lower than customers’ expectations in lower power distance cultures (Dash et al. 2006). Huang et al. (1996) posit that the larger the power distance in a country, the more likely are the consumers to perceive unsatisfactory services as a fact of life, and are less prone to complain. Consequently, we expect that any action taken by the service company to restore satisfaction after the service failure will be more valued by those cultures high in power distance. Thus, we should observe higher (lower) effect sizes for high (low) power distance cultures in the relationships between each perceived justice construct and SATCOM.

Masculinity versus its opposite, femininity, refers to the distribution of emotional roles between the genders (Hofstede 1997). Masculine cultures tend to be ambitious and need to excel, whereas feminine cultures consider quality of life and helping others to be very important. Masculine cultures care much more about exchange outcomes than about relationships among people. As such, they should be more sensitive to such outcomes as the dimensions of distributive justice. McFarlin and Sweeney (2001) suggest that in masculine cultures people would be more concerned with clear performance standards, consistency and accuracy of application of company procedures, implying a receptiveness towards procedural justice. On the other side, feminine cultures are much more concerned about human relationships; hence they should be more sensitive to the interpersonal treatment received while handling the service problem than masculine cultures. Based on this, we expect higher (lower) effect sizes in masculine (feminine) cultures in the distributive justice→SATCOM and procedural justice→SATCOM relationships, whereas we expect higher (lower) effect sizes in feminine (masculine) cultures in the relationship between interactional justice and SATCOM.

Uncertainty Avoidance deals with a society’s tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity. Uncertainty avoiding cultures try to minimize the possibility of novel situations by rules, security measures, and by establishing long-term relationships. The opposite type, uncertainty accepting cultures, is more tolerant of opinions different from what they are used to; they try to have as few rules as possible, and accept risk and relativistic positions. Consequently, high uncertainty avoiding cultures should be even more sensitive to the redress offered by the service company because it represents a mean to reduce the anxiety and the stress caused by the service failure. Thus, we expect higher (lower) effect sizes for high (low) uncertainty avoiding cultures between distributive justice and SATCOM. High uncertainty avoiding cultures need structured relationships and call for immediate and professional response in unclear situations (Reimann et al. 2008; Patterson et al. 2006). As such, the behavior of the contact personnel in handling the complaint situation and the rules of the organization might play an increased role in satisfaction evaluations. Thus, we expect higher (lower) effect sizes for high (low) uncertainty avoidance cultures for the procedural justice→SATCOM and interactional justice→SATCOM relationships.

Method

Selection of studies

We conducted an on-line search on electronic databases and an off-line search on leading academic journals. In addition, we used Google Scholar, ServNet, and AFMNet to retrieve the “fugitive literature” (Rosenthal 1995). We retrieved more than 80 published and unpublished studies, which were checked for measures of the relationships of the antecedents and consequences of SATCOM (Rosenthal 1991). The correlations were the most common metric available in these studies, but we converted F values with one df in the numerator, and t-values into r’s using available formulas (Rosenthal 1991) if necessary. When experiments presented more than two levels in the manipulated variable (high-medium-low designs), resulting in multivariate F tests, we contrasted the high vs. low conditions. In total, we obtained 509 usable correlations from 60 independent samples drawn from 50 papers. Some studies that investigated SATCOM correlates could not be included in our analysis for one or a combination of the following reasons: (1) some were theoretical rather than empirical papers, (2) some used the Critical Incident Technique, (3) some investigated constructs that appear in our model but did not include SATCOM or included a different variable (e.g., overall satisfaction, service encounter satisfaction), and (4) some did not provide enough data and the authors were unable to retrieve either the results or the original database. In reviewing the literature, we identified three characteristics of the constructs related to SATCOM. First, different studies employed different names for the same construct. Hence, we categorized concepts sharing the same meaning into one single construct reporting a satisfying average interrater reliability (Fleiss’ kappa = 0.93). Second, some constructs appeared far more frequently than others. We did not include in the analysis several correlates of SATCOM because of the small number of effects (less than five). The small number of effects retrieved for several correlates of SATCOM reflects the tendency of researchers to include new constructs and to avoid exact replications. This tendency impedes, among others, the analysis of their relative effects in a multivariate model. Infrequent antecedents of SATCOM include: expectations (2 studies), service importance (2 studies), equity (2 studies), and several service recovery attributes and failure context characteristics that have been tested directly on SATCOM (1 study). Infrequent consequences of SATCOM include commitment (1 study) and trust (2 studies). Finally, we found substantial agreement on the causal ordering of the effects. Table 1 provides information about the main characteristics of the selected studies that have investigated the correlates of SATCOM.

Meta-analytic procedure

The analysis of the data and the reporting of findings proceeded in the three following steps.

Analysis of pairwise relationship: correcting and describing effect sizes

In this stage we provided an overview of pairwise relationships involving SATCOM. We adjusted correlations for corrections due to measurement and sampling errorsFootnote 1 (Hunter and Schmidt 2004), examined their credibility intervals, and computed multiple tests to approach the question of homogeneity of effect sizes for each relationship (Geyskens et al. 2009).

Multivariate moderator model: analyzing the joint effects of moderators

We estimated two separate models to assess whether methodological and cultural moderators account for the variance in the effect sizes. Distinct analyses are necessary because for methodological moderators we hypothesize similar effects across antecedents and outcomes, whereas for the cultural moderator we expect different effect across the antecedents. Moderator models were estimated using generalized least squares to explicitly model within-study dependencies (e.g., Geyskens et al. 1998):

In each model, y represents the vector of the reliability-corrected correlations, b contains the regression coefficients to be estimated, and Σ is the large sample variance covariance matrix (Becker 1992).Footnote 2 In the methodological moderator model Z represents the matrix that contains the vectors of methodological moderators coded as dummy variables. In this model we also included six dummy variables indicating the type of construct correlated with SATCOM. The number of nonzero elements in a column of Z constitutes a sort of partial sample size; hence the ratio of the largest to smallest eigenvalues of Z’Z must be in the range of 50 or less for inversion, which means that 5% or more of the sample should involve a particular column of Z (Farley et al. 1995). All the dummy variables included in our model represent more than 5% of the sample. Since we included a dummy variable for each construct category, we did not include an intercept. In the cultural moderator model the Z matrix contains four vectors with the Hofstede’s scores of cultural dimensions.

Causal model: estimating the nomological network

The causal analysis proceeded in three steps. First, we tested the homogeneity between two pooled adjusted average correlation matrices (Brown and Peterson 1993).Footnote 3 Second, we used the complete adjusted average correlation matrix (Table 2) as input to LISREL 8.52 to fit the structural equation hypothesized model. Finally, we performed the analysis to test the mediating role of SATCOM (Iacobucci 2008).

Results

Analysis of pairwise relations

Table 3 shows that antecedents vary substantially in their influence on SATCOM. Among the three dimensions of justice, distributive justice is most strongly related to SATCOM (r = 0.65). This strong correlation highlights the central role of compensation in a service failure situation. Interactional justice has the second largest effect (r = 0.52), while procedural justice ranks third (r = 0.45).

SATCOM varies also in its influence on consequences. Positive WOM is strongly related to SATCOM (r = 0.64), although this relationship appears susceptible to a file-drawer problem. The relationship between SATCOM and return intent ranks second (r = 0.46); the relationship between SATCOM and overall satisfaction towards the firm ranks third (r = 0.38).

Analysis of the effects of moderators

The tests for homogeneity (Geyskens et al. 2009) suggest that variability among effect sizes continues to exist after correcting for sample size and reliability. To account for the joint effect of these moderators in explaining this variability in the effect sizes we performed two multivariate analyses. Tables 4 and 5 show results of the analysis of the effects of methodological and culture moderators respectively.

On average, significant methodological moderators are participants, number of industries, and measurement level (b 2 = 0.37, b 3 = 0.12, and b 4 = −0.23 respectively). Results indicate that the use of student samples produces on average higher coefficients, providing support for the biases documented by Park and Lessig (1977) and Burnett and Dunne (1986). The inclusion of multiple industries also contributes to produce stronger effect sizes, supporting the idea that greater variation in service contexts generates stronger correlation coefficients. Finally, when SATCOM is measured using only a single-item scale higher effect sizes can be observed. Although some prior research indicated that the use of multi-item scales taps the domain of the construct more completely (e.g., Brown and Peterson 1993) our results indicate that, when dealing with the SATCOM construct, a single-item measure generates higher effect sizes on average. As expected, all the regression coefficients for the type of construct are significant and different from each other.

Results of Table 5 show that the cultural moderators differently affect the relationships between perceived justice constructs and SATCOM.

A focus on the statistically significant effects reveals that the relationship between interactional justice and SATCOM is higher in individualistic cultures (0.35), a result that is consistent with our prediction. Contrary to our predictions, effect sizes are lower in high power distance cultures for the relationships between SATCOM and interactional (−0.38) and procedural justice (−0.23). This result could depend on the status of the employee that manages the complaint. For example, Patterson et al. (2006) found that in high power distance cultures a high status of the employee positively affects justice perceptions. Similarly, our results might indicate that, if the employee who manages the complaint is perceived low in status, the effect of interactional and procedural justice on SATCOM are lower in high power distance cultures. The degree of masculinity/femininity of a culture does not affect the relationship between justice dimensions and SATCOM.

Uncertainty avoidance moderates the relationship between interactional and procedural justice and SATCOM; effects sizes are higher in uncertainty avoiding cultures (0.61 and 0.59 respectively). This result is in line with our predictions about the importance that a reassuring behavior of the contact personnel, and clear company procedures hold in these cultures.

Finally, it is worth noting that the relationship between distributive justice and SATCOM is not affected by any cultural dimension, suggesting a “universal” importance of this outcome-related dimension (Patterson et al. 2006).

Causal model

In total, 52 studies provided information for the causal model analysis with a median sample size of 3214. The model hypothesizes a positive effect of justice dimensions on SATCOM, which, in turn, is supposed to have a positive impact on WOM, return intent, and overall satisfaction. Part of the customer satisfaction and of the complaint handling literature theoretically and empirically supports additional paths of causal relationships between the three outcomes of SATCOM. Overall satisfaction is supposed to have a positive effect on positive WOM and on intention to return. Finally, positive WOM is supposed to relate positively with return intent, suggesting that individuals tend to behave in accordance with their cognition (e.g., Szymanski and Henard 2001).

Results of the hypothesized model are presented in Fig. 2. This model presents a good fit (χ2(1) = 4.94, p < 0.03, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.042, RMSR = 0.0005) and results are in line with the literature.

Figure 2 illustrates the path coefficients of the structural model. Each justice dimension has a significant although relatively different effect on SATCOM. Distributive justice has the highest impact on SATCOM (γ11 = 0.45), followed by interactional justice (γ12 = 0.25) and procedural justice (γ13 = 0.09). In turn, SATCOM has a strong, positive effect on WOM (β21 = 0.53), and a nonsignificant effect on overall satisfaction and on return intent. A nonsignificant effect is also observed between overall satisfaction and WOM. Finally, both WOM and overall satisfaction significantly affect return intent (β24 = 0.24 and β34 = 0.50 respectively).

Table 6 reports the results for the paths that support full or partial mediation. We found support for H1a; SATCOM mediates the effects of justice dimensions on WOM. Full mediation was supported for distributive justice→WOM, and for procedural justice→WOM. Partial mediation was supported for the path interactional justice→WOM.

The path from SATCOM to overall satisfaction is not significant; so is the effect of SATCOM on return intent. Therefore, H1b and H1c were not supported in our analysis.

Discussion and conclusions

Through this work we attempted to provide a quantitative synthesis of 20 years of research on satisfaction with complaint handling in services. Drawing on justice theory and the customer satisfaction framework we identified three justice dimensions and three focal outcomes as antecedents and consequences of SATCOM. We used a powerful technique—meta-analysis—to explain the variability of findings observed across studies. We assessed the absolute and relative strength of justice dimensions on SATCOM, analyzed the characteristics of the study design that may generate differences in the findings across studies, and tested the role of SATCOM as central mediator between its antecedents and consequences. We discuss the theoretical and managerial implications next.

Our findings show that the main interest of the empirical studies has been in the effects of perceived justice on SATCOM. Among the three dimensions of perceived justice, distributive justice has the strongest average correlation with SATCOM: customers expect the company to restore the service promise through a fair redress. This result parallels the importance of the Reliability dimension of the SERVQUAL scale in the satisfaction literature (Zeithaml et al. 1990). Complaining customers consider the capacity to re-establish the promised service to have the most influence on their satisfaction after the complaint.

Interactional justice yields on average the second highest effect size. This result is interesting if we compare it with procedural justice. It suggests that the quality of the interpersonal treatment customers receive after a service failure has, on average, a stronger impact on satisfaction than the perceived fairness of procedures. In other words, employees’ empathy, politeness, and willingness to provide reasonable explanations are more highly related to SATCOM than the flexibility or the time needed to execute the procedures.

Among the consequences, positive word of mouth has the highest average correlation with SATCOM. This strong positive effect converges with the similar result found in the meta-analysis on customer satisfaction of Szymanski and Henard (2001), and confirms the well-known tendency of service customers to share their satisfying or dissatisfying service experience with other people (File et al. 1994; Anderson 1998). SATCOM holds the second highest effect with return intent, and the third with overall satisfaction, suggesting that a well-managed complaint produces positive effects on both affective and conative components of consumer attitudes.

Several study characteristics moderate the relationships between SATCOM and its correlates. Our model shows that, all relationships considered, participants, number of industries, and measurement level significantly account for the variance of the relationships involving SATCOM. Therefore, researchers should be aware that the use of student samples generates on average higher correlations. In addition, the inclusion of multiple industries produces stronger estimated relationships between SATCOM and its correlates. Finally, the way of measuring SATCOM explains part of the differences in the effect sizes.

Culture moderates to some extent the relationships between SATCOM and justice dimensions. Researchers should note that in individualistic cultures, estimates of the relationship between interactional justice and SATCOM tend to be higher on average. In addition, high power distance cultures produce lower effect sizes in the relationships between interactional and procedural justice and SATCOM. Uncertainty avoiding cultures generate higher effect sizes in the relationship between interactional and procedural justice and SATCOM, suggesting, for these cultures, a more important role of the contact personnel and the company’s policies in handling the complaint situation. Interestingly, the relationship between distributive justice and SATCOM is not affected by any cultural dimension, which suggests that distributive justice is equally important across culture.

The meta-analytic assessment of the causal effects involving SATCOM has important implications for both theory and practice since it provides an insightful picture of the nature of the structural relationships between justice dimensions, SATCOM, and its outcome variables. In addition, the analysis sheds light on the mediating role of SATCOM, which has not been clarified in the literature.

Distributive justice was found to exert the strongest effect on SATCOM. This result confirms the prominence of distributive justice over the other justice dimensions across different studies. This result corroborates previous empirical findings (e.g., Mattila and Patterson 2004; Homburg and Fürst 2005; Smith et al. 1999; Severt 2002; Pizzi et al. 2008) and disconfirms the major role of interactional justice (e.g., Tax et al. 1998; Davidow 2000; Smith and Bolton 2002). Interactional justice has the second highest effect on SATCOM. The crucial role of contact personnel, which has long been recognized in the service quality (Zeithaml et al. 1990) and human resources research (Schneider and Bowen 1993), clearly emerges from our findings.

Finally, procedural justice has a significant but very weak effect on SATCOM, reflecting a minor role for this type of justice in customer evaluations. This result suggests that the structural aspects of procedures are, on average, not as important as the implementation of procedures. In the organizational literature, Bies and Moag (1986) argue that people rely on interactional justice when deciding how to react to authority figures, whereas they draw on procedural justice when deciding how to react to the organization as a whole. In service situations, complaints are often managed by contact personnel; accordingly, it might be that customers rely more on the interactional than the procedural dimension of justice.

Our theoretical framework posits SATCOM as an intervening variable in the process through which justice dimensions impact outcome variables. Findings of the mediation analysis indicate that SATCOM mediates the effect of justice dimensions on WOM. This evidence confirms the crucial role of SATCOM on the well-known tendency of service customers to voice their experience to other people. This result is particularly important because positive WOM, in turn, has a significant effect on return intent, indicating a consistency between what customers say to other people and their intentions to behave (Szymanski and Henard 2001).

Our results also indicate that the mediating role of SATCOM is not supported for the relationships between justice constructs and return intent. A possible explanation for this evidence is that in this framework two types of satisfaction are included: a transactional form of satisfaction, SATCOM, and a long-term form of satisfaction, overall satisfaction. On the one side, SATCOM triggers customers to tell other people their story due to salience and recency of their experience (Maxham and Netemeyer 2002). On the other side, overall satisfaction, which considers the customers’ history of the transactions with the company, more powerfully predicts return intent than any one single satisfactory transaction. Hence, the absence of a mediating role of SATCOM on the relationship between justice constructs and return intent might be due to the fact that a more stable attitude, overall satisfaction, better captures the intention to make future business with the same company.

The path between SATCOM and overall firm satisfaction does not support mediation. This result might be explained by the number of complaint-free transactions with the service company. Customers who have experienced a small number of failures in their exchange relationship may weight SATCOM for a first time failure less in expressing their overall satisfaction (Maxham and Netemeyer 2002). Since the majority of our studies considers the occurrence of one single service failure, it is plausible that SATCOM does not shape the overall satisfaction judgment.

Our findings highlight three theoretical aspects of the complaint handling framework: (1) the role played by each dimension of perceived justice, (2) the mediating role of SATCOM, and (3) the role of SATCOM consequences—overall satisfaction, return intent, and positive WOM—in this framework. Each of these aspects carries implications for research.

First, we emphasize that, because of their specific role in certain types of cultures, all justice dimensions should be included in complaint handling models. This inclusion has not always been present in empirical studies. Our meta-analysis indicates that distributive justice plays a dominant role in determining SATCOM, which might lead researchers to infer that customers focus mainly on compensation, and therefore to exclude other dimensions of justice from the analysis. However, such an approach would miss the important role of the other forms of justice on the construction of SATCOM in certain cultures. Individualistic cultures, for example, rely on the interactional, human-related dimension of perceived justice to restore their satisfaction. In low power distance and in high uncertainty avoiding cultures the individual behavior of contact personnel and the organizational behavior that is coded in policies and procedures are particularly effective in re-establishing satisfaction.

Second, we show that SATCOM mediates the relationship between each justice dimension and positive WOM, but it does not for overall satisfaction and return intent. This result is important, as research on the mediating role of SATCOM is rare, and findings have been mixed at best. Past research has often paralleled the mediating role of SATCOM to the mediating role of overall satisfaction (e.g., Tax et al. 1998); our results suggest that this parallel may not be accurate, and call for more research on the relationships among evaluative constructs in the complaint handling domain.

Third, we strongly recommend the inclusion of all the relevant outcome variables, such as return intent, WOM, and overall satisfaction. If relevant outcome variables are excluded, researchers risk obtaining only a partial picture of the complex structure of relationships underlying the complaint handling framework. Moreover, including outcome variables increases the managerial relevance of complaint management for service firms.

Our findings may help managers to efficiently allocate company resources to achieve successful recovery effects. For example, immediately providing a fair compensation results in customers’ positive evaluation of the specific episode, this in turn generates positive WOM. Hence, if the purpose is maintaining brand awareness among existing customers, increasing the customer base, and achieving risk-averse customers, then fair outcomes combined with staff courtesy and fairness of procedures are likely to quickly produce positive WOM. When a firm cannot provide immediate compensation, we suggest conveying the type of compensation that will be provided. We expect that the promise of compensation will evoke pre-consumption mental imagery, where the consumer vicariously experiences the satisfaction of the redress before the actual experience (MacInnis and Price 1987). Such anticipated satisfaction is likely to lower the possibility of the consumer engaging in negative WOM.

Since compensation is crucial, we suggest managers to set the minimum reward that should be offered and understand what type of compensation is preferred by the customer. Managers should also think about what kind of organizational design would best lead customers to perceive that, in case of a failure, a fair compensation will be surely provided. For example, who should hold the responsibility and the power to give the compensation?

Next, management should know that a service failure episode is not likely to have a negative effect on the level of overall satisfaction of the customer base. Service recovery systems are important because they prepare the organization to react to potential problems. However, customer intention to patronage the service firm is not directly affected by the satisfaction with how the complaint was managed, but by a holistic, cumulative assessment of the provider.

Finally, multinational service companies should take into account the cultural differences of the countries in which they operate. For example, managers should be aware that in high individualistic cultures (e.g. U.S., Australia, and Great Britain) the contact personnel should be trained and empowered to manage the service failure effectively since its specific behavior contributes significantly to restore the level of satisfaction. In low power distance cultures (e.g. Austria, Denmark, Israel), and in high uncertainty avoiding cultures (e.g. Greece, Portugal, Japan) attention should be placed both on the training of contact personnel, and on the clearness, accessibility and fairness of the complaint handling procedures because these cultures particularly appreciate these dimensions of justice.

Limitations

Although this meta-analysis expands our knowledge of SATCOM, it is subject to certain limitations. First, our analysis did not account for every antecedent of SATCOM. We addressed only those constructs for which sufficient primary data were available. For example, our causal model does not include severity of the service failure among the SATCOM antecedents. In addition, we were not able to formally include in our model the service recovery attributes and failure context characteristics (Smith et al. 1999). Thus, the potential bias for omitted variables exists, and our framework should be considered as a summary of the most common correlates of SATCOM. Second, although several studies suggest that the magnitude of the relationship between SATCOM and its antecedents and consequences might change if different types of services are considered (Maxham and Netemeyer 2002; Seiders and Berry 1998), we were not able to meaningfully disentangle the effect of different types of service. Finally, because of the limited number of studies considering online services, we did not compare online versus offline services. The online context presents distinctive characteristics and asks for a better understanding of how SATCOM antecedents and consequences behave in such a context.

Further research

A meta-analytic study offers the opportunity to suggest several avenues for further research. Drawing on our results, on the suggestions of Davidow (2003) and Parasuraman (2006), and on existing work (Holloway et al. 2005), we propose in Table 7 a research agenda for the years to come.

Through this meta-analysis we have attempted to illuminate the relationships among the most commonly studied constructs involving SATCOM. We believe that the results will serve as a guide and an incentive for scholars willing to pursue research in the complaint handling domain further.

Notes

Correlation coefficients were adjusted with an attenuation factor calculated as the product of the square root of (1) the reliability of the independent variable, (2) the reliability of the dependent variable, and (3) the sample size (Hunter and Schmidt 2004). Cronbach’s alpha values of each study were used as an indicator of the reliability of dependent and independent variables. However, not all studies reported Cronbach’s alpha. When they were unavailable we used imputation procedures (Becker 1992), and we imputed reliably from studies that were as similar as possible to those with missing data. However, the great majority of the studies reported Cronbach’s alpha, only 3% presented missing values. The average Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are: 0.87 for SATCOM, 0.91 for distributive justice, 0.89 for interactional justice, 0.87 for procedural justice, 0.89 for return intent, 0.90 for WOM, and 0.88 for overall satisfaction.

We asked authors for the correlation matrix whenever this information was not reported in the studies. In case of non-response, we imputed correlations from similar studies (Becker 1992). Three studies (Chung 2006, Lapidus and Pinkerton 1995, and Brown et al. 1996) were dropped because of lack of correlation coefficients and unavailability of enough information to perform a meaningful imputation.

One was built using all available adjusted correlation coefficients, the other using only the effect sizes coming from a reduced set of homogeneous studies, i.e., only those studies that contained jointly all the constructs included in the causal model. The aim of this analysis is to test whether the two matrices are homogeneous and can be pooled (see Brown and Peterson 1993, Appendix, for a similar approach). We tested the equivalence between the two matrices through a two-group confirmatory factor analysis. Since the test indicated that the complete adjusted average correlations were equivalent (χ2 = 28.18, p = 0.14, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 0.99, RMSEA = 0.031, RMSR = 0.02), in the second step we used the complete adjusted average correlation matrix.

References

Ambrose, M., Hess, R. H., & Ganesan, S. (2007). The relationship between justice and attitudes: an examination of justice effects on event and system-related attitudes. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 103, 21–36.

Anderson, E. W. (1998). Customer satisfaction and word of mouth. Journal of Service Research, 1(1), 5–17.

Andreassen, T. W. (2000). Antecedents to satisfaction with service recovery. European Journal of Marketing, 34(1/2), 156–175.

Becker, B. J. (1992). Using results from replicated studies to estimate linear models. Journal of Educational Statistics, 17(4), 341–362.

Bies, R. J., & Moag, J. S. (1986). Interactional Justice: Communication Criteria of Fairness. In R. J. Lewicky, B. H. Sheppard, & M. H. Bazerman (Eds.), Research on Negotiation in Organizations. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, (1) 43–55.

Blodgett, J. G., Hill, D. J., & Tax, S. S. (1993). The effects of perceived justice on complainants’ negative word-of-mouth behaviour and repatronage intentions. Journal of Retailing, 69(4), 339–426.

Blodgett, J. G., Hill, D. J., & Tax, S. S. (1997). The effect of distributive, procedural and interactional justice on postcomplaint behavior. Journal of Retailing, 73(2), 185–210.

Boshoff, C. (1997). An experimental study of service recovery options. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 8(2), 110–30.

Brown, S. P., & Peterson, R. A. (1993). Antecedents and consequences of salesperson job satisfaction: meta-analysis and assessment of causal effects. Journal of Marketing Research, 30(1), 63–77.

Brown, S. W., Cowles, D. L., & Tuten, T. L. (1996). Service recovery: its value and its limitations as a retail strategy. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 7(5), 32–46.

Burnett, J. J., & Dunne, P. M. (1986). An appraisal of the use of student subjects in marketing research. Journal of Business Research, 14(4), 329–343.

Cameron, C. A., & Windmeijer, F. A. G. (1997). An R-squared measure of goodness of fit for some common nonlinear regression models. Journal of Econometrics, 77, 329–342.

Chung, C.-C. (2006). When service fails: the role of the salesperson and the customer. Psychology and Marketing, 23(3), 203–224.

Clemmer, E. C., & Schneider, B. (1996). Fair service. In T. A. Swartz, D. E. Bowen, & S. W. Brown (Eds.), Advances in services marketing and management. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, (2)13–229.

Colquitt, J. A., Conlon, D. E., Wesson, M. J., Porter, C. O. L. H., & Ng, Y. K. (2001). Justice at the millennium: a meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 425–445.

Dash, S., Bruning, E., & Guin, K. K. (2006). The moderating effect of power distance on perceived interdependence and relationship quality in commercial banking: a cross-cultural comparison. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 24(5), 307–326.

Davidow, M. (2000). The bottom line impact of organizational response to customer complaints. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research, 24(4), 473–490.

Davidow, M. (2003). Organizational response to customer complaints: what works and what doesn’t. Journal of Service Research, 5(3), 225–250.

Farley, J. U., Lehmann, D., & Sawyer, A. (1995). Empirical marketing generalization using meta-analysis. Marketing Science, 14(3), 36–46.

File, K. M., Cermak, D. S. P., & Prince, R. A. (1994). Word-of-mouth effects in professional services buyer behavior. The Service Industries Journal, 14(3), 301–314.

Fornell, C., & Wernerfelt, B. (1987). Defensive marketing strategy by customer complaint management: a theoretical analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 24(4), 337–346.

Geyskens, I., Steenkamp, J.-B., & Kumar, N. (1998). Generalizations about trust in marketing channel relationships using meta-analysis. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 15(3), 223–248.

Geyskens, I., Krishnan, R., Steenkamp, J.-B., & Cunha, P. V. (2009). A review and evaluation of meta-analysis practices in management research. Journal of Management, 35(2), 393–419.

Harris, K. E., Grewal, D., Mohr, L. A., & Bernhardt, K. L. (2006). Consumer responses to service recovery strategies: the moderating role of online versus offline environment. Journal of Business Research, 59(4), 425–431.

Hofstede, G. (1997). Cultures and organizations: Softwares of the mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Holloway, B. B., Wang, S., & Parish, J. T. (2005). The role of cumulative online purchasing experience in service recovery management. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 19(3), 54–66.

Homans, G. C. (1961). Social behavior: Its elementary forms. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World.

Homburg, C., & Fürst, A. (2005). How organizational complaint handling drives customer loyalty: an analysis of the mechanistic and organic approach. Journal of Marketing, 69(3), 95–114.

Huang, J.-H., Huang, C.-T., & Wu, S. (1996). National character and response to unsatisfactory hotel service. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 15(3), 229–243.

Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. (2004). Methods of meta-analysis. correcting error and bias in research findings. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Iacobucci, D. (2008). Mediation analysis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Lam, S. Y., Shankar, V., Erramilli, M. K., & Murthy, B. (2004). Customer value, satisfaction, loyalty, and switching costs: an illustration from a business-to-business service context. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 32(3), 293–311.

Lapidus, R. S., & Pinkerton, L. (1995). Customer complaint situations: an equity theory perspective. Journal of Psychology and Marketing, 12(2), 105–118.

Liao, H. (2007). Do it right this time: the role of employee service recovery performance in customer-perceived justice and customer loyalty after service failures. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 475–489.

Lind, A. E., & Tyler, T. R. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. New York: Plenum.

MacInnis, D. J., & Price, L. L. (1987). The role of imagery in information processing: review and extensions. Journal of Consumer Research, 13, 473–491.

Mattila, A. S., & Patterson, P. G. (2004). Service recovery and fairness perceptions in collectivist and individualist contexts. Journal of Service Research, 6(4), 336–346.

Maxham, J. G., III. (2001). Service recovery’s influence on consumer satisfaction, positive word-of-mouth, and purchase intentions. Journal of Business Research, 54, 11–24.

Maxham, J. G., III, & Netemeyer, R. G. (2002). Modelling customers perceptions of complaint handling over time: the effects of perceived justice on satisfaction and intent. Journal of Retailing, 78(4), 239–252.

Maxham, J. G., III, & Netemeyer, R. G. (2003). Firms reap what they sow: the effects of shared values and perceived organizational justice on customers’ evaluations of complaint handling. Journal of Marketing, 67(1), 46–62.

McFarlin, D., & Sweeney, P. (2001). Cross-cultural applications of organizational justice. In R. Cropanzano (Ed.), Justice in the workplace: From theory to practice (pp. 67–96). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

National Association of Consumer Agency Administration. (2005). Thirteenth Annual NACCA/CFA Consumer Complaint Survey Report.

Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 24(11), 460–469.

Oliver, R. L. (1997). Satisfaction: A behavioral perspective on the consumer. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Parasuraman, A. (2006). Modelling opportunities in service recovery and customer managed interactions. Marketing Science, 25(6), 590–593.

Park, W. C., & Lessig, P. V. (1977). Students and housewives: differences in susceptibility to reference group influence. Journal of Consumer Research, 4(2), 102–110.

Patterson, P. G., Cowley, E., & Prasongsukarn, K. (2006). Service failure recovery: the moderating impact of individual-level, cultural value orientation on perceptions of justice. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 23(3), 263–277.

Pizzi, G., Forti, E., Pareschi, L., & Orsingher, C. (2008). Antecedents and consequences of service recovery process in experimental studies: A meta-analysis. EMAC Conference Proceedings, 27–30 May, Brighton, UK.

Reimann, M., Lunemann, U. F., & Chase, R. B. (2008). Uncertainty avoidance as a moderator of the relationship between perceived service quality, and customer satisfaction. Journal of Services Research, 11(1), 63–73.

Rosenthal, R. (1991). Meta-analytic procedures for social research. London: Sage.

Rosenthal, R. (1995). Writing meta-analytic reviews. Psychological Bulletin, 118(2), 183–192.

Schneider, B., & Bowen, D. E. (1993). The service organization: human resources management is crucial. Organizational Dynamics, 21(4), 39–52.

Seiders, K., & Berry, L. L. (1998). Service fairness: what it is and why it matters. The Academy of Management Executive, 12(2), 8–20.

Severt, D. E. (2002). The customer’s path to loyalty: A partial test of the relationships of prior experience, justice, and customer satisfaction. Ph.D. dissertation. Virginia Polytechnic Institute at Blacksburg.

Smith, A. K., & Bolton, R. N. (2002). The effect of customers’ emotional responses to service failures on their recovery effort evaluations and satisfaction judgments. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30(1), 5–23.

Smith, A. K., Bolton, R. N., & Wagner, J. (1999). A model of customer satisfaction with service encounter involving failure and recovery. Journal of Marketing Research, 36, 356–372.

Soares, A. M., Farhangmehr, M., & Shoham, A. (2007). Hofstede’s dimensions of culture in international studies. Journal of Business Research, 60(3), 277–284.

Sobel M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13, 290–312.

Spreng, R. A., Harrell, G. D., & Mackoy, R. D. (1995). Service recovery: impact on satisfaction and intentions. Journal of Services Marketing, 9(1), 15–23.

Stauss, B. (2002). The dimensions of complaint satisfaction: process and outcome complaint satisfaction versus cold fact and warm act complaint satisfaction. Managing Service Quality, 12(3), 173–183.

Szymanski, D. M., & Henard, D. H. (2001). Customer satisfaction: a meta-analysis of the empirical evidence. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 29, 16–35.

Tax, S. S., Brown, S. W., & Chandrashekaran, M. (1998). Customer evaluations of service complaint experiences: implications for relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 62(2), 60–72.

Zeithaml, V. A., Parasuraman, A., & Berry, L. L. (1990). Delivering quality service: Balancing customer perceptions and expectations. New York: The Free Press Division of Macmillan.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the editor, David W. Stewart, and the four anonymous JAMS reviewers for their insightful critiques of this manuscript. In addition the authors thank Gian Luca Marzocchi for his suggestions on previous versions of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The complete list of studies included in the meta-analysis is available from the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Orsingher, C., Valentini, S. & de Angelis, M. A meta-analysis of satisfaction with complaint handling in services. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 38, 169–186 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-009-0155-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-009-0155-z