Abstract

Although stress research has received increased attention in the behavioral and social sciences, it has been virtually ignored by marketing researchers. This paper attempts to advance the stress perspective as a useful framework in consumer research. First, the author presents theoretical and conceptual foundations of stress research. Second, the author develops a general conceptual model of the causes and consequences of stress on the basis of theory and research. The model serves as a blueprint for presenting theory and research on stress, organizing and interpreting findings of consumer studies in the context of stress theory, and developing propositions for needed research. Finally, the author provides a research agenda to guide future studies in this area.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Although the concept of stress is an important topic in the behavioral sciences, it has received little attention in the field of marketing. Recent research suggests that marketing researchers and practitioners have much to gain by understanding the reasons consumers experience stress and how they attempt to cope with it (Duhachek 2005; Viswanathan et al. 2005).

Previous marketing studies have addressed stress in the context of life changes, suggesting that people change their consumption habits in an effort to cope with the stress inherent in life changes (e.g., Lee et al. 2001). Other studies have viewed stress as a contributor to the development of undesirable consumer behaviors such as materialism and compulsive consumption (e.g., Rindfleish et al.1997). Despite recent interest among marketing researchers in the area of stress, the role of stress in consumer behavior and its implications for marketing practice have received relatively little attention and systematic examination.

This research builds on extant literature in the social sciences and the limited research in the consumer field to advance the notion that stress might help the understanding of a wide variety of consumer behaviors. First, I discuss the concept of stress, its causes and consequences, and how it relates to consumer behavior. Second, I present a general conceptual model that serves as a blueprint for presenting theory and research on stress, for organizing and interpreting findings of consumer studies in the context of stress research, and for developing propositions for needed research. Third, I develop a research agenda to guide future studies in this area.

The concept of stress

Although there are few areas of contemporary psychology that have received more attention than stress (Hobfoll 1989), researchers disagree on how to conceptualize and study stress. The term “stress” is broadly defined as a stimulus, a response, or a combination of both. Stimulus definitions focus on external conditions, that is, on life situations or events (e.g., accidents, loss of spouse) that are, by definition, stressful. The key assumption about these experiential circumstances that give rise to stress (often known as “stressors”) is that all change (positive or negative) is potentially harmful because change requires readjustment (Pearlin 1989). Stimulus-based definitions, which rely on the investigator’s appraisal of whether the stimulus is stressful, are popular. According to one estimate, as of the late 1980s, there had been more than 1,000 studies using one inventory of stressors alone to study the relationship between life changes and diverse forms of disorder (Monroe and Peterman 1988).

Response definitions refer to a state of stress; the person is viewed as being under stress, reacting with stress, and so on (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Unlike stimulus definitions, which assume an objective view of stress, investigators who employ response definitions view stress as a subjective state (George 1989). Subjective definitions of stress are becoming increasingly popular because response-based definitions are more useful and subject to less criticism (Elder et al. 1996; George 1989).

Sociologists and psychologists also distinguish between two main forms of stress: acute stress and chronic stress. “Acute stress” (also known as the “life-event” form of stress) refers to “discrete, observable events which are thought to be threatening because they represent change” (Wheaton 1990: 210). The various life-event checklists (e.g., Cohen 1988; Lee et al. 2001; Tausig 1982) assume an acute and objective definition of stress, in which most life-event measures inquire about events experienced during the recent past.

Conversely, “chronic stress” refers to “continuous and persistent conditions in the social environment resulting in a problematic level of demand on the individual’s capacity to perform adequately in social roles” (Wheaton 1990: 210). Also known as “chronic strains,” this type of stress is the result of problems rooted in institutionalized social roles because the activities and interpersonal relationships they entail are enduring. Examples of chronic strains include role overload (e.g., occupational roles), interpersonal conflicts within role sets (e.g., parent–child, husband–wife), and interrole conflict (e.g., incompatible demands of work and family). Chronic stress is distinguished from acute stress primarily by its longer duration.

In this research, I use response definitions of acute and chronic stress. Acute stress refers to an event or situation that is evaluated as stressful by the consumer and requires mental and behavioral adjustments within a relatively short period, whereas chronic stress refers to persistent or recurrent demands that require adjustments over prolonged periods (e.g., disabling injury) (Thoits 1995).

Causes and consequences of stress

Causes of stress

Theories of stress

Although stress models have been used since the1920s, theory development in stress research began in psychology in the 1950s with the work of Selye (1956), who focused on changes as the underlying mechanism of stress. According to this perspective, stress involves internal or external changes of sufficient magnitude to threaten the organism’s homeostatic equilibrium. Life events are regarded as sources of personal dislocation because they create instability among inner forces, and stress is a signal that the organism is struggling to reestablish stability and equilibrium (Pearlin 1982). The view that change is the underlying mechanism of stress is shared by researchers who developed or used life-event scales to measure the degree of change in thousands of studies over the past four decades (e.g., Monroe and Peterman 1988; Thoits 1995)

More than 20 years later, sociologists (e.g., Pearlin et al. 1981) proposed a distinctive theory of social stress guided by both interactionist and role perspectives. This theory accounts for people’s subjective interpretation of events and the social context that affects the stress process. Interactionist theories highlight the social construction of reality, and role theories address the problems of social location and transition, conflicting obligations, and task overload (Elder et al. 1996). Thus, social stress theory emphasizes the mediators and moderators of stress and has transformed stress research from an over-simplified focus on the strength and robustness of the relationships between a person’s experience of events and outcomes (typically mental and physical illness) to a more fine-grained emphasis on the conditions under which stress has or does not have negative consequences (Elder et al. 1996). This new theoretical orientation has led to definitions and measures of subjective perceptions of stress experienced by the individual. Although response-based definitions are subject to the individual’s state or condition, with the condition varying according to the specific disturbances or contexts, a major criticism of stimulus-based definitions is that people respond differently to the same potentially stressful situations (Houston 1987). Therefore, according to prior research (e.g., Elder and O’Rand 1995; Elder et al. 1996; Norris and Uhl 1993), response-based definitions are more useful and subject to less criticism than stimulus-based definitions. Thus, the mere experience of an expected or unexpected event may not be a source of stress unless it is subjectively evaluated as such.

Interdependence of events

Life events are interdependent (Pearlin 1989). Some occur first in experience and are known as primary stressors; other events are secondary or consequences of the primary stressors (Pearlin 1989). People may not be aware of or may ignore the increase in the likelihood of the dependent event, which in turn may create stress. For example, studies suggest that the most adverse effects produced by a divorce result from deprived life conditions after the divorce, such as income decline, rather than from the divorce itself (Elder and O’Rand 1995). Furthermore, some events create the anticipation of future events as in the case of first-time pregnancy leading to parenthood.

Acute and chronic stress

Pearlin (1989) observed that though stress researchers often focus on life events or role strains, the study of stress is not an “either-or” proposition. He further explains:

Studies of events typically examine the events as direct causes of stress in individuals. Yet events also cause stress in an indirect manner by altering adversely the more enveloping and enduring life conditions. These conditions, in turn, become potent sources of stress in their own right—perhaps more potent than the precipitating event (p. 247).

Extensive research shows that stress is present not only in unexpected events and life status changes (e.g., early widowhood; Cohen 1988), but also in highly scheduled or anticipated life-cycle changes and in the enactment of normative roles (e.g., worker, parent, spousal; Pearlin 1982). For example, Balkwell (1985: 577–578) summarized the results of studies of loss of spouse to death, stating: “In addition to the stress generated by grief is the tension induced because widowhood is an ambiguous role that offers little guidance for appropriate behavior.” Adjustments of one’s lifestyle to an anticipated event or role transition can be stressful (Pearlin 1982), and uncertainty or lack of clarity about many of the anticipated events or roles may lead to chronic stress. People seem to have a desire to organize their experiences into a consistent, understandable, and predictable system, and prolonged uncertainty and lack of clarity about anticipated events or roles can thwart this desire and lead to chronic stress (Gierveld and Dykstra 1993; Houston 1987). Mergenhagen (1995) cited several examples and studies that show how anticipation of life events and transitions most common to people in later stages of life create ongoing strains. Thus, a person’s experience of an expected or unexpected event may be the source of acute or chronic stress, to the extent that he or she evaluates the life condition created by the event as stressful.

Consumer behaviors as stressors

Many consumer decisions, such as buying or remodeling a house and having major dental work, have been viewed as stressful events and have been included in life-event scales (e.g., Moorman 2002; Tausig 1982). Consumption-related stress can be experienced before and after purchase or consumption (e.g., Mick and Fournier 1998); it can derive from discrepancies between desired and actual states related to various stages in consumer decision making. Need recognition implicitly assumes a psychological imbalance due to changes in the environment or changes in the organism (i.e., a definition of stress; Thoits 1995: 54), both actual and anticipated. Needs for products, which are often conflicting (e.g., technology paradoxes), can also create stress (Mick and Fournier 1998). Similarly, budgeting for purchases involves decisions on priorities about consumption needs that may create conflict and stress (e.g., Sujan et al. 1999). At the information-seeking stage, the concept of perceived risk assumes a psychological imbalance due to a lack of information or perceived ability to choose wisely, suggesting the presence of stress as a function of the amount of perceived risk or uncertainty (Schwartz 2004; Viswanathan et al. 2005). Similarly, cognitive conflict (ambiguity) due to too many choices or information overload may increase the level of stress at the evaluation stage (e.g., Luce 1998; Schwartz 2004). At the purchase stage, consumers may experience stress as a result of product unavailability, the inability to locate and evaluate products, long checkout lines, and the required method of payment (Sujan et al. 1999; Viswanathan et al. 2005). Finally, at the postpurchase stage, stress can derive both from unexpected product or service performance, which may create a state of dissatisfaction (e.g., Duhachek 2005), and from experiencing uncertainty about one’s choice because of exposure to dissonant information (Schwartz 2004). Thus, greater stress experienced at each stage of the decision process suggests higher levels of consumer involvement with the product or purchase, underscoring the importance of stressful consumption situations over the nonstressed ones.

Furthermore, major consumer decisions (e.g., the purchase of a house) may be viewed as primary stressors (Pearlin 1989) because they increase the probability of occurrence of other consumption and nonconsumption events that can have long-lasting effects. Various types of consumer actions have been viewed as a hierarchy of interdependent choices (i.e., events) that range from budgeting to specific choices (e.g., Gould et al. 1993; Wells 1993), and many of them lead to stressful events. For example, the purchase of a house in certain coastal areas can lead to the purchase of certain products and services (e.g., flood insurance) and increases the family’s probability of experiencing a natural disaster and resultant long-term emotional and economic hardship. Similarly, family budget problems can create stress and lead to divorce that, in turn, may lead to additional financial problems due to reduced income (Elder and O’Rand 1995). Thus, consumption events can lead to non-consumption events, and vice versa.

Moderators of consumption-related stress

Stress research suggests that the stressfulness of an event depends on two main factors: the type of event and the characteristics of the person (e.g., Cohen 1988; Norris and Murrell 1984; Thoits 1995; Wheaton 1990). Four event characteristics appear to affect the stressfulness of an event: its importance, desirability, and controllability and whether the event is expected or unexpected (e.g., Cohen 1988; Monroe and Peterman 1988). Important events have a greater impact than unimportant or irrelevant events, negative or undesirable events create more stress than positive or desirable events, events that a person can influenced (controlled) are less stressful than events beyond his or her control, and unanticipated events create more stress than anticipated events. On the basis of these findings and recent consumer research (Viswanathan et al. 2005), it is expected that consumption-related stress is present only in consumption situations that are important to consumers (e.g., high involvement, risky decisions) and, therefore, that event desirability, controllability, and (un)expected event occurrence are relevant only in important consumption situations.

Furthermore, it is expected that undesirable consumer decisions (e.g., major dental work) create more stress than desirable ones (e.g., car purchase) and that uncontrollable consumer choices are more stressful than controllable consumer decisions (e.g., the decision to fly “standby” versus having a confirmed reservation). Finally, a person has more time to prepare (e.g., seek more information to reduce risk) for important anticipatory consumer decisions than for decisions that are unexpected and must be made within a relatively short period (e.g., car replacement due to length of use versus unexpected severe damage). Thus, it is expected the event’s importance, desirability, controllability, and (un)expected occurrence similarly affect the stressfulness of a consumption-induced event.

Several other individual-related factors were found to moderate the impact of life events. For example, strong resources, such as self-esteem, social support, socioeconomic status (SES), and urban location, tend to reduce the likelihood of experiencing acute stress (Norris and Murrell 1984; Thoits 1995). These and other similar factors may also moderate the impact of stressful consumption-related events and, thus, the stress related to the various stages of the decision-making process. For example, illiteracy is likely to increase stress in consumer decisions, even for unimportant purchases (Viswanathan et al. 2005).

Consequences of stress

Theoretical perspectives

Selye (1956) viewed stress as a psychological reaction against any form of noxious stimulus; he called this reaction general adaptation syndrome. In this perspective, stress was not viewed as an environmental demand (which Selye called “stressor”) but as a universal psychological set of processes and reactions created by such a demand. Research in psychology and sociology has viewed acute and chronic stress as processes (e.g., Elder et al. 1996; George 1989; Pearlin et al. 1981), focusing on the relationships between the two types of stress and their consequences on a person’s emotional and physical well-being. In the early 1980s, a series of articles argued that life events (acute stress) may affect a person indirectly through the exacerbation of role (chronic) strains (e.g., Kanner et al. 1981; Pearlin et al. 1981). The direct and indirect effects of life events through chronic stress have been demonstrated empirically for several events, including involuntary job loss, divorce, loss of spouse (Pearlin 1989), and natural disasters (Norris and Uhl 1993).

In recent years, there has been increasing recognition that “while stress is an inevitable aspect of the human condition, it is coping that makes the big difference in adaptation outcome” (Lazarus and Folkman 1984: 6). Lazarus and Folkman (1984: 141) define coping as “constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person.” According to this definition, coping includes any cognitive or behavioral effort to manage stress, regardless of how well or badly it works. Coping implies effort, which helps differentiate coping from automatized adaptive behavior. As Lazarus and Folkman state, “many behaviors are originally effortful and hence reflect coping, but become automatized through learning processes” (p.140).

In general, theory posits that by creating disequilibrium, stressors motivate efforts to cope with behavioral demands and with the emotional reactions they usually evoke (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). More recent theoretical formulations also view coping as an outcome of cognitive imbalanced states. For example, according to the theory of mental incongruity (Gierveld and Dykstra 1993), which integrates and extends different lines of theory on attitude–behavior consistency, a way to resolve disruptions of balanced states is by behavioral adaptation. The central postulate of the theory is that “if equilibrium is disrupted then there is a tendency to redress balance, and thus to relieve the frustrations and unpleasant social experiences accompanying disequilibrium” (Gierveld and Dykstra 1993: 209). Thus, the person may initiate or intensify cognitive and overt activities to alleviate stress and restore his or her psychological equilibrium.

Coping strategies

Although it is widely accepted by psychologists and sociologists that when people are faced with forces that adversely affect them, they do not remain passive but actively react by employing various coping strategies (Pearlin 1982), considerably less is known about the specific strategies people use to reduce stress. Coping strategies are behavioral and cognitive attempts to manage stressful situational demands (Lazarus and Folkman 1984); they are large in number and are likely to vary across stressful situations. People may use different coping strategies in various social structures (Lazarus and Folkman 1984; Pearlin 1989).

Stone et al. (1988) reviewed and classified methods of coping with stress found in the psychological literature into problem solving (rational decision making), avoidance (cognitive or behavioral), tension-reduction behaviors (e.g., exercising), social support (from family and friends), information seeking (from the professional community), situation redefinition (viewing the situation differently and diminishing its perceived severity), and religiosity (e.g., praying). Lazarus and Folkman (1984) classified coping responses into problem-focused and emotion-focused. Coping strategies that are directed at solving the problem or managing the stressful situation (i.e., information seeking, finding alternative channels of gratification, choosing among alternatives, developing new standards of behavior, and engaging in direct action) are problem-focused. In contrast, emotion-focused coping strategies are intended to manage resultant emotions primarily through cognitive processes, such as avoidance, selective attention, and seeking out consonant information from the environment that minimizes threat.

These and other coping strategies, such as active versus avoidance coping, have been viewed in the context of control theories (for a discussion of these strategies, see, e.g., Heckhausen and Schulz 1995). An underlying assumption of all control theories is the notion that humans desire to produce behavior-event contingencies and thus exert primary control over the environment (White 1959). On the basis of this premise, Heckhausen and Schulz (1995) proposed a theory-based and perhaps more useful framework for classifying coping strategies. These and other investigators (e.g., Rothbaum et al. 1982) maintain that coping strategies can be classified as either primary control strategies (or problem-focused strategies), which involve activities targeted at the external world, or secondary control (or emotion-focused strategies), which involve activities internal to the individual (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). A number of other factor-analytic solutions are reported in the literature (e.g., Duhachek 2005), in which solutions likely to differ depending on respondent characteristics (e.g., age; Schulz and Heckhausen 1999) or the context of assessment (e.g., actual experience of stress vs. hypothetical scenarios).

In summary, the information presented in this section suggests that a person’s subjective evaluation of various experienced life events and circumstances, including important purchases, is the sources of acute and chronic stress. In turn, stress requires a response (coping), which can include the initiation or intensification of consumption activities. The person’s prolonged experience of stress and his or her coping responses lead to certain physical, emotional, cognitive, affective, and behavioral changes. Finally, several contextual variables moderate a person’s experience of stress and his or her coping responses.

The effects of stress on consumer behavior

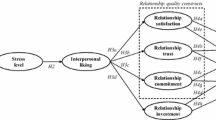

Although consumer behaviors can cause stress (as discussed previously), of greater interest among consumer researchers appears to be the study of the effects of stress on consumer behavior (e.g., Andreasen 1984; Burroughs and Rindfleish 2002; Lee et al. 2001; Mathur et al. 2003; Mick and Fournier 1998; Pavia and Mason 2004. In this section, I introduce a model that shows the effects of stress on consumers (see Fig. 1). The model serves as a blueprint for presenting theory and research on stress and guides the development of research propositions and agenda for future research. First, I present theory and research that are relevant to the relationships among model elements or components (i.e., sources of stress, consumption-related coping responses, outcomes, and moderating variables). Second, I develop a set of propositions that are related to specific variables within the model components.

The information presented in the previous section suggests two types of influence of stress on consumer behavior. First, stress can have direct effects, such that changes in consumer behaviors are viewed as coping responses to stress. Second, stress can alter patterns of consumer behavior, in which such alterations do not reflect coping responses, such that elevated levels of stress may affect decision making, physical and subjective well-being.

Consumer behaviors as coping responses

New evidence in stress research suggests that because people are motivated to protect and enhance their well-being, they may deliberately engineer positive events in their lives (Thoits 1995). In line with the homeostatic drive-reduction model, positive events have been viewed both as stressors and as useful in reducing internally or externally induced aversive states (Reich and Zautra 1988). An underlying need in the process of being satisfied was assumed whenever the organism acted (Miller and Dollard 1941). Within the broader context of drive-reduction and activation theories, Reich and Zautra (1988: 153) identified a class of events as positive not only because the events reduce aversive arousal, but also because they “promote feelings of relief and satisfaction of needs through avoidance, escape, and/or consumatory behaviors.” Thus, the distinction between a consumer activity as a stressful event and a consumer activity as a coping strategy depends on the activity’s short-term effect on the consumer. An activity is viewed as a stressor when it creates a psychological disequilibrium; it is viewed as a coping response when it helps restore balance. However, the same activity may have different long-term consequences. For example, some activities, such as alcohol consumption and shopping, may help reduce stress, but their excessive use over time might create family conflict (i.e., chronic stress).

Within the context of need satisfaction suggested by the activation and drive-reduction theories, which have been offered as explanations of a person’s initiation of positive events in general, two other theoretical perspectives have been proposed that specifically link stress to various types of consumption activities that may be viewed as coping responses. First, the uses-and-gratifications paradigm has been widely used in mass communications research to help explain interest in advertising content, use of special-interest magazines, and other types of media consumption (O’Guinn and Faber 1991). The basic premise of this perspective is that people may use various types, amounts, and media contents to satisfy psychological needs, including aversive states such as stress and boredom. Several consumption phenomena have been suggested that might be profitably examined from a uses-and-gratifications perspective (O’Guinn and Faber 1991). Second, escape theory has been proposed to explain overconsumption of specific products, such as food, alcohol, and drugs (Heatherton and Baumeister 1991). According to this perspective, people experiencing stress may consume products that help them become less self-aware of the consequences of stressful events and circumstances. For example, “alcohol has been shown to reduce self-focus, and in stressful situations people will drink to avoid awareness” (Heatherton and Baumeister 1991: 91). This theory has been proposed as a general comprehensive theory that integrates many previous contributions and may apply to a wide variety of consumption phenomena (Heatherton and Baumeister 1991; Hirschman 1992).

A typology of coping responses

Whereas several studies have suggested that consumers engage in a variety of activities to reduce stress, only two consumer studies have attempted to develop typologies for classifying specific consumer behaviors as coping strategies. Mick and Fournier’s (1998) typology, which Viswanathan et al. (2005) also used, considers behaviors consumers use to cope with decisions as either confrontative or avoidance strategies that are related to both the preacquisition and consumption stages of the decision process. This typology excludes nonconsumption-coping strategies that consumers use to handle consumption-induced stress (e.g., Duhachek 2005; Sujan et al. 1999). In contrast, Duhachek’s (2005) study identifies nonconsumption—coping strategies, but this typology does not show specific consumption—coping behaviors at the predecisional stage of the decision process. The source of stress is assumed to derive from hypothetical stressful consumer episodes (scenarios) of primarily purchase consequences. Neither Mick and Fournier’s nor Duhacheck’s study appears to provide an exhaustive typology of the possible coping responses to stress because both assume that consumption-coping responses can be initiated only in response to consumption situations. However, the information presented in previous sections suggests that the source of stress can be related to both consumption and nonconsumption activities and events. Similarly, coping responses can be both consumption and nonconsumption related. Thus, the two types of stress sources and coping responses produce a fourfold typology (Table 1).

Within each cell of the typology, the coping responses can be further distinguished as both primary or confrontative, which mainly include behaviors directed at the external environment, and secondary or avoidance, which include cognitive and behavioral activities directed at the self and reflect attempts to “fit in with the world and to flow with the current” (Heckhausen and Schulz 1995: 285). The list of coping responses in each cell in Table 1 is by no means exhaustive. The nonconsumption coping list under “life-event-induced stress” includes only a small sample of coping responses (for additional coping responses, see Lazarus and Folkman 1984), and the other cells include only coping responses found in consumer studies (as shown at the bottom of Table 1).

Conceptually, consumption-induced stress can be distinguished from event-induced stress in three ways. First, the former is internal to the consumer decision process (i.e., it is generated at various stages of the process), whereas the latter is external to consumer decision states (i.e., it is created by events and roles external to the consumer decision process). The second distinction pertains to the person’s responses to the two types of stress. Because consumption-induced stress can be experienced at different stages of the decision process, coping strategies tend to focus on alleviating stress at each decision stage. In contrast, consumption-coping responses to event-induced stress tend to focus on the consumption stage rather than the process of product or service acquisition. It is mainly the consumption of the product that alleviates averse emotions (e.g., Hirschman 1992; Pavia and Mason 2004), though some aspects of the acquisition process (e.g., shopping) may also have similar effects (e.g., Hirschman 1992; O’Guinn and Faber 1989). However, even when the same strategy is employed for the two types of stress, the differences in the underlying needs satisfied in the process (e.g., problem-solving vs. escape) make the strategy theoretically distinct. The third distinction can be made with respect to the relative effectiveness of the two types of consumption coping strategies (confrontative or primary vs. avoidance or secondary) in handling stress. Whereas avoidance strategies have been found to be less effective than confrontative strategies in reducing event stress (physical and psychological strains), and they may even aggravate distress and adversely affect a person’s self-esteem (Thoits 1995), avoidance strategies used to cope with consumption-induced stress do not appear to be inferior to confrontative strategies and tend to help enhance the person’s self-esteem (Mick and Fournier 1998).

The fourfold typology provides a better understanding of consumer behavior (see Table 1). Thus, for example, shopping may be viewed either as a preacquisition confrontative (primary) coping strategy when the source of stress is in consumer decision making (Mick and Fournier 1998) or as an avoidance (secondary) coping strategy when the source of stress is a nonconsumption event (e.g., Faber et al. 1987; Hirschman 1992). This suggests the need to study a specific consumption-coping response in the context of a consumer’s motivation for engaging in an activity, a notion that is in line with the uses-and-gratifications perspective. For example, television viewing is considered an avoidance strategy when it is undertaken to alleviate aversive feelings (e.g., anxiety, stress, boredom); it is considered a confrontative strategy when the motive is information gathering for effective consumer decision making (e.g., O’Guinn and Faber 1991). The interest in the current study is primarily in the consumer behaviors used to handle stress due to consumption- and life-event-induced stress. Thus, the remainder of the discussion in this section is devoted to developing propositions about consumer behavior that may change or differ in response to both event- and consumption-induced stress. The propositions are suggested by previous theory and research; they are related both to categories and to specific variables within each category.

Stress and consumption-coping behaviors

A search for the causes of the differential impact of stress and subsequent coping responses has produced two research traditions. The first tradition depends on the stressfulness of the event or situation because of differences in characteristics such as unpredictability, undesirability, and magnitude. The second relies on the differential vulnerability argument in which the impact of events and the coping responses reflect differences in coping resources or strategies and other individual characteristics such as age and SES (e.g., Thoits 1995; Wheaton 1990).

Effects of event- and consumption-induced stress

Although expected life events and transitions are stressful (e.g., Balkwell 1985; Pearlin 1982), they are not as stressful as unexpected life events or transitions because they allow time for preparation (Gierveld and Dykstra 1993). Given that most transition events are scheduled or anticipated (e.g., employment, marriage, parenthood, grandparenthood, retirement) they may require different coping responses. Specifically, it can be speculated that transition events should initiate more primary coping and, therefore, more confrontative coping strategies than nontransition events. Conversely, nontransition events, such as natural disasters and accidents, do not allow for preparation; thus, they may not only create more stress but also result in less efficient consumer-coping strategies.

Proposition 1

When consumers experience a stressful life event, they are likely to (a) use preacqusition confrontative-coping strategies to the extent that the event is expected rather than unexpected and (b) preacquisition avoidance-coping strategies to the extent that the event is unexpected rather than expected.

The same reasoning may apply to stressful consumer choices. To the extent that unplanned or unexpected consumer decisions are more likely to create stress than planned or expected decisions, consumption-coping strategies will also differ. Mick and Fournier (1998) research suggested that unexpected consumption situations, such as the receipt of an unwanted and unexpected gift, increase the likelihood of consumer avoidance strategies over confrontative strategies. Thus, consumers are expected to use relatively more consumption avoidance-coping strategies for unplanned stressful decisions than for planned purchases.

Proposition 2

Unexpected stressful purchases are (a) less likely to generate consumption confrontative-coping and (b) more likely to generate consumption avoidance-coping strategies than are planned or expected stressful consumer decisions.

Not only are the types of consumption-coping strategies likely to differ between a planned and an unplanned purchase, but so are specific confrontative-coping strategies. Uncertainty in a purchasing decision may create stress that can lead to confrontative strategies, such as information seeking to reduce uncertainty, and to behaviors aimed at reducing negative consequences of the purchase. For example, in Mick and Fournier’s (1998) research, some consumers attempted to reduce paradox-induced stress by extending decision making, which involved information seeking to reduce uncertainty and make a sound decision; others attempted to cope with stress by engaging in activities such as buying heuristics (e.g., buying familiar, reliable brands) and buying insurance to cover unexpected emergency repairs (i.e., reduce negative consequences). Mick and Fournier’s (1998) and Schwartz’s (2004) analyses of consumer behaviors for managing paradoxes parallel consumer behaviors for managing risk, in which consumer strategies focus on either decreasing uncertainty or decreasing the negative consequences of the decision. Paradoxes and risks both entail stress that requires coping responses, because in both cases consumers experience psychological disequilibria. Given that planned stressful purchases allow more time for decision making than unexpected stressful purchases, it is expected that consumers employ different consumption confrontative-coping strategies.

Proposition 3

Consumers who plan for a purchase decision are (a) more likely to use preacquisition confrontative-coping strategies aimed at decreasing uncertainty about their options and (b) less likely to use preacquisition confrontative-coping strategies that reduce the possible negative consequences of their decision than are consumers who must make an unexpected purchase decision.

In a parallel vein, effort to cope with less than adequate information might affect a consumer’s use of evaluative strategies. Such efforts may focus more on minimizing losses (i.e., undesirable consequences) than on maximizing expected benefits, suggesting a shift in evaluative strategies from lexicographic to conjunctive.

Proposition 4

Consumers who must make an unexpected purchase decision are (a) more likely to use conjunctive rules and (b) less likely to use lexicographic rules in product evaluation than are consumers who plan for a purchase decision.

The use of consumption confrontative-coping strategies is not always stress-free. Schwartz (2004) presented evidence that suggests that consumers who consider a large number of options are also more likely to experience stress due to conflict associated with difficulty in making trade-offs, which increases the likelihood of “no decision.” Luce’s (1998) findings appear to support this line of reasoning. Furthermore, exposure to a large number of alternatives tends to diminish the attractiveness of any single option because of the increase in the number of attractive features likely to be noticed in the different options (Schwartz 2004).

Proposition 5

The greater the numbers of alternatives consumers consider, the greater is the likelihood that they will (a) not make a decision and (b) experience dissatisfaction with their purchase.

Moderators of stress and consumption coping

A key question for sociologists and psychologists is whether coping strategies and coping styles differ by demographic characteristics such as age and SES (Thoits 1995). With respect to age, Heckhausen and Schulz (1995) discussed how biological and societal life-course constraints (e.g., chronic illness) may explain age-related differences in a person’s coping strategies. While the use of problem-focused (primary-control) and emotion focused (secondary-control) strategies increase during childhood and early adulthood, primary control strategies are expected to decline during advanced adulthood and old age (Heckhausen 2002). Declines in working memory and long-term memory are common explanations for reduced use of primary-control strategies. With increasing age, the use of problem-focused (primary control) strategies becomes a risky proposition because of the increasing probability of failure. The risk of failure is believed to make the use of emotion-focused (secondary control) strategies more attractive (Heckhausen and Schulz 1995), though an alternative explanation for the increased preference can be offered by the socioemotional selectivity theory (e.g., Lockenhoff and Carstensen 2004).

Proposition 6

Older consumers who experience a stressful life event are (a) less likely to use preacquisition confrontative-coping strategies and (b) more likely to use preacqusition avoidance-coping strategies than are younger consumers.

Proposition 7

Older consumers who experience a stressful purchase decision are (a) less likely to use preacquisition confrontative-coping strategies and (b) more likely to use preacquisition avoidance-coping strategies than are younger consumers.

Explanations for the changes in the coping strategies over a person’s life span may contribute to understanding of why people of different ages engage in specific consumption activities when they experience stress at different stages of the decision-making process. At the information-seeking stage, decreasing knowledge gathering at advanced ages has been attributed both to cognitive declines (e.g., older adults seek less information because they want to avoid complexity) and to shifts in goals proposed by socioemotional selectivity theory ( Lockenhoff and Carstensen 2004). Control theory and socioemotional theory predict a lower propensity to seek information with increased age. Stress induced from the importance of a decision and the decision’s perceived complexity is likely to increase a younger person’s likelihood of seeking information (i.e., selective-primary control strategy), and it should increase the use of compensatory-control strategies among older adults (Heckhausen 2002). For example, when consumers are unable to seek or use information, they may delegate coping to others as a coping strategy (Viswanathan et al. 2005). Similarly, older adults’ increased emphasis on using prior experience rather than new information (Moschis 1992) could be a compensation for reduced analytical skills (Lockenhoff and Carstensen 2004).

In a similar vein, coping responses to stressful consumption situations are expected to differ between younger and older adults when they evaluate products. Compared with their younger counterparts, older adults are expected to engage in compensatory-control strategies such as delegating decisions to others. For example, studies show that older adults are more likely than younger adults to refer health-related choices to their doctors and relatives rather than deciding themselves (Lockenhoff and Carstensen 2004).

Proposition 8

The greater the level of stress due to uncertainty experienced in a purchase decision, the greater is the probability that older adults, will (a) seek less information, (b) use prior experience, and (c) delegate decision making to others, compared with younger adults.

The available evidence further suggests age-related differences in the types of consumption confrontative-coping strategies because of biological changes that affect a person’s ability to process information (e.g., sensory loss, slowing of the central nervous system) (Moschis 1992). The aging consumer is increasingly less likely to use evaluative strategies and more likely to use heuristics when experiencing stress at the product evaluation stage. The greater reliance on brand name and brand loyalty found among older consumers than their younger counterparts (Moschis 1992) may reflect differences in confrontative consumption-coping due to age-related deficits.

Proposition 9

Age moderates the relationship between stress experienced at the product evaluation stage and the types of consumption confrontative-coping strategies use. Thus, older consumers are (a) more likely to use heuristics and (b) less likely to use product-attribute evaluations than are their younger counterparts.

Available literature also suggests age-related differences in coping behaviors at the post-purchase or postdecisional stage. Older people have been consistently found not to seek information before using a product (Moschis 1992). Furthermore, research suggests that older people are more likely than younger adults to use prior experience to solve problems of medication adherence and nutrition and to attend more to positive than to negative information; younger people show the reverse pattern (Lockenhoff and Carstensen 2004). The reliance on prior experience and the preference for positive-valence information may prevent older adults from processing disconfirming information. This may explain the lower levels of cognitive dissonance experienced by older adults and, subsequently, the higher levels of satisfaction with their purchases (Moschis 1992).

Proposition 10

The greater the level of stress experienced at the purchased stage, the greater is the likelihood that older adults will use (a) consonant over dissonant information and (b) prior experience to evaluate product performance, compared with younger adults.

People in different social structures use different primary and secondary coping strategies, which may be due to different socialization practices in different social structures (Thoits 1995). Recent empirical work suggests that SES differences in coping abilities reflect more than just access to financial resources; rather, they reflect differences in socialization of people in different social classes that leads to the development of resilient personality characteristics (Elder and O’Rand 1995). For example, studies show that middle-class children are likely to believe that success and failure is a matter of personal effort, whereas lower-class children attribute success to chance and circumstances beyond their control (Kagan 1977). This suggests that upper-class families socialize their children to use problem-focused coping while the lower-class families socialize their children to emotion-focused coping. Thus, it can be speculated that upper SES consumers engage in relatively more consumption confrontative-coping strategies and fewer consumption-avoidance coping strategies. Furthermore, because lower-class persons are relatively isolated from the paths of experience of dominant middle class (Hess 1970: 468), and because they have “little awareness of specific alternatives, and little disposition to weigh evidence” (p. 488), they will be more likely to use confrontative strategies that involve buying heuristics and less likely to use extended decision making that involves product evaluations based on attributes.

Proposition 11

Upper-SES consumers who experience stressful life events are (a) more likely to employ preacquisition confrontative-coping strategies and (b) less likely to employ preacquisition avoidance-coping strategies than are lower-SES consumers.

Proposition 12

Socioeconomic status moderates the relationship between stress experienced at the product evaluation stage and the types of preacquisition confrontative-coping strategies used. Thus, lower-SES consumers are more likely to use heuristics and (b) less likely to use product-attribute evaluations than are upper-SES consumers.

Stress and noncoping consumer behaviors

Changes in consumer behavior may not always reflect coping responses. Stress may also promote the development of consumer skills and affect a person’s decision-making patterns. Significant life events, especially those that signify transitions to new roles (e.g., death of spouse into widowhood), create cognitive demands and opportunities for growth because the person’s response to demands of changing life conditions promotes the development of new skills (Turner and Avison 1992). Specifically, life events that signify transitions to new roles are stressful because of the person’s effort to establish a new identity (Wheaton 1990), which also involves the acquisition and disposition of products that help define his or her new self-concept consistent with the new social role (e.g., Young 1991). Furthermore, many role transitions require the person to perform activities he or she has had little experience in performing, forcing the development of new skills (e.g., McAlexander et al. 1993). In particular, multiple roles involve people in relatively complex social environments, which are believed to foster intellectual growth and management skills (Elder et al. 1996).

Stressful life changes may affect consumer behavior at every stage of the decision process, in which such behaviors do not represent coping responses. First, at the need recognition stage, a transition to a new role might increase the person’s knowledge about certain products that are relevant to the enactment of the acquired role. For example, an increased knowledge about long-term-care insurance might develop as a result of a person’s assumption of the role of a caregiver to an older relative.

Second, the available literature also suggests that negative mood states, such as stress, may inhibit effective information processing and decision making (e.g., O’Guinn and Faber 1991; Schwartz 2004), though the reasons are unclear. It is possible that the experience of a stressful life event depletes the person’s cognitive and emotional resources because he or she is trying to cope with stress using nonconsumption-coping strategies, adversely affecting his or her ability to make optimal or beneficial choices (Andreasen 1984). Major acute or chronic stressors may interfere with a consumer’s ability to make thoughtful and extended decisions, leading to information processing at lower levels of elaboration and the use of heuristic rules when purchasing products. For example, Pavia and Mason (2004) noted that for many people, the horror of a cancer diagnosis and the fear of their situation interfered with even simple purchases and routines, such as the ability to balance a checkbook and buy grocery products. Another study found that highly aroused participants evaluated ads on the basis of peripheral cues, whereas moderately aroused viewers were influenced more by the strength of the ad’s arguments (Sanbonmatsu and Kardes 1988). Finally, Anglin et al. (1994) showed that stressed consumers tend to be price sensitive, suggesting that they may use heuristic rules or nonevaluative strategies.

Proposition 13

The greater the amount of life-event stress consumers experience during the purchasing process, the greater is their likelihood of (a) processing information at a lower level of elaboration, (b) using category-based processing, and (c) using heuristics.

Third, at the purchasing stage, stress may affect a person’s brand choices. Andreasen (1984) theorized that when consumers experience stressful life changes, they tend to stay with the brands they normally use because they do not want to deal with more changes in their lives. The data supported his hypothesis that chronic stress is negatively related to brand preference changes. Although the desire to use the same brand may be viewed as a coping strategy in the case of consumption-induced stress, stability in consumer preferences in response to chronic stress does not appear to reflect a coping response. Rather, this type of stress taxes consumers’ emotional resources, interfering with their interest and ability to consider other brands.

Finally, previous research suggests that life-event stress affects the consumer’s satisfaction with products. The relationship between stress and life satisfaction is well established in the psychological literature, showing that experience of stress contributes to dissatisfaction with life (e.g., Burroughs and Rindfleish 2002). Andreasen (1984) asserted that stress also has a negative effect on consumer satisfaction, and he presented cross-sectional data to support his contention. O’Guinn and Faber (1991) suggested that Andreasen’s findings regarding the relationship between chronic stress and consumer satisfaction should be viewed in the context of the uses-and-gratifications perspective. This perspective can be used to compare gratifications sought in purchase decisions with those obtained from such purchases. In this context, the person’s level of stress experienced during the purchasing process would be expected to have a bearing on the difference between expectations or needs (gratifications sought) and product performance or need satisfaction (gratifications received). To the extent that any form of stress interferes with effective decision making (Schwartz 2004), it is expected to lead to suboptimal consumer choices and, consequently, to greater dissatisfaction with the purchase.

Proposition 14

Purchase satisfaction is inversely related to the amount of (a) event-induced stress and (b) consumption-induced stress.

Long-term consequences of stress and coping responses

People may engage in a variety of consumption-related activities to reduce stress, and many consumption-related coping behaviors, such as use of psychotropic drugs and impulsive shopping, may be temporal activities that do not cause significant long-term alterations in already-established patterns of consumer behavior; they may cease or disappear after stress is reduced, and they may not appear until another stressful situation arises. Although stressful experiences and coping responses viewed as temporal changes may not lead to the development of long-lasting changes in patterns of consumer behavior, they may gradually lead to a wide variety of physical, mental, and behavioral changes (see Fig. 1).

Research in psychology and medicine has focused primarily on health consequences of stress and coping. The relationships among stress, coping, and health have been extensively studied in medical and psychological research (e.g., Cohen 1988; Thoits 1995). The inability to handle stress leads to various types of physical and emotional health problems and disorders, which are also viewed as events (see Fig. 1; Tausig 1982). Conversely, the ability to cope with stress and the use of effective coping strategies promote physical and emotional well-being and longevity. Thus, it can be expected that consumption-related stress and coping responses have long-term consequences on the person’s consumption patterns and well-being. To the extent that problem-focused coping is more effective in reducing or buffering the negative effects of stress on a person’s physical and emotional well-being (Thoits 1995), it can also be expected that preacquisition and postdecision confrontative-coping strategies have similar consequences on the person’s health. It might be that emotion-focused coping in general and consumption avoidance-coping strategies in particular result in less beneficial choices or outcomes that create dissatisfaction with behavior, adversely affecting a person’s physical and emotional well-being.

Proposition 15

A consumer’s health is positively associated with the use of (a) preacquisition confrontative-coping strategies and (b) postdecision confrontative-coping strategies, and it is negatively associated with the use of (c) preacquisition avoidance-coping strategies and (d) postdecision avoidance-coping strategies.

Previous research suggests that the acquisition of material helps consumers reduce stress and reestablish a sense of control over their lives, leading to the development of materialistic values (Burroughs and Rindfleish 1997; Pavia and Mason 2004; Rindfleish et al. 1997). However, Burroughs and Rindfleish (2002) also viewed stress as a consequence of materialism and a key mediator of the relationship between materialism and subjective well-being (SWB), but only among people with high levels of collective-oriented values. Specifically, materialism had a significant negative effect on SWB among people who place emphasis on family and religion, but it had no effect on those with community-oriented values. These findings beg the question: Are the negative consequences of materialism on SWB among people who have high collective-oriented values due to the different coping responses they have used over time to handle stressful situations?

In the Burroughs and Rindfleish’s (2002) study, the correlations between stress and materialism (0.20), stress and happiness (−0.35), and stress and life satisfaction (−0.36) were higher than the correlations between materialism and the latter two measures of SWB (−0.15 and −0.25, respectively). It might be that stress is a key causal factor in the development of these orientations, especially among people who use secondary (emotion-focused) strategies under stressful conditions, such as praying and seeking emotional support from family members (see Table 1; Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Such strategies are considered less effective in reducing or buffering the negative effects of stress (Thoits 1995). Conversely, people who place greater value on community issues may be more integrated socially and have greater access to sources of information that could promote the use of primary (problem-focused) coping strategies, which tend to be more effective in neutralizing the negative effects of stress on SWB. This might be the reason Burrough and Rindfleish (2002) found that materialism and SWB were significantly related only among people with strong family and religious (but not community) values which are likely to promote the use of secondary coping strategies.

Proposition 16

Life-event stress is likely to have a negative effect on a person’s SWB to the extent that he or she holds (a) family-oriented values and (b) religious values.

Implications for marketing research

The review of stress research in the context of the general conceptual framework presented suggests several topics of potential interest to marketing researchers. At a conceptual level, a better understanding is needed on the differences between consumption-induced stress and other event-induced stress. That is, knowledge is needed on whether the two types of stress require different coping responses and how such coping responses might affect a person’s consumer behavior and well-being in general. In a similar vein, a better understanding is needed on the effects of acute and chronic stress. Although life events are the cause of both acute and chronic stressors, do consumers respond differently to the two types of stress? In general, most previous consumer studies do not distinguish between the effects of these stressors. It may be that consumers use different consumption-coping strategies that, in turn, may have different long-term effects on them. Furthermore, the information presented suggests the need to understand how stress alters consumption patterns in which such changes do not reflect coping responses. Specifically, does event-induced and consumption-induced stress affect a consumer’s ability to make beneficial choices? If so, what aspects of the decision process do they affect, how do they affect them, and why?

A fruitful area of research along these lines is the investigation of consumer exposure to marketer-controlled tactics or strategies (which may be viewed as events) that may create consumption-induced stress (e.g., limited offer periods or stock, long lines at cash registers, ad appeals aimed at creating anxiety or dissonance). A better understanding is needed on the types of consumers who are affected by marketing strategies that create stress. People who have not developed effective strategies to cope with stressful consumption encounters are expected to experience greater psychological dislocation (cognitive imbalance, stress), which forces them to make a greater number of adjustments to their attitudes and beliefs. A lack of such strategies might have adverse effects on a consumer’s well-being. A better understanding is also needed on marketer-controlled strategies that could help consumers cope with stress present in a purchase decision. Certain marketing tactics or changes in existing tactics (e.g., replacing live counselors with voice-recognition automated telecommunication systems) would need to be reassessed in terms of their long-term benefits. Stress-inducing consumption encounters would be expected to create higher levels of stress and dissatisfaction with the marketer, whereas tactics that help consumer cope with stressful encounters would increase consumer satisfaction and loyalty.

A fundamental theoretical issue presented herein is whether models in marketing are adequate in capturing consumers’ emotional and cognitive states. For example, models of rational decision making and information processing place great emphasis on cognitive states that are stress free. Thus, future studies might need to reexamine the predictive ability of these models under stressful conditions and, perhaps, to enrich such models by examining the possible interactions of emotions with cognition. Therefore, research in this area should address the following questions:

-

1.

How do different types of stressors (acute and chronic) affect consumer decision processes?

-

2.

Do acute and chronic stressors lead to different patterns of information processing that may result in suboptimal consumer choices?

-

3.

Which information processing elements (e.g., perceptual system, short-term memory, encoding, retrieval), if any, are influenced the most by specific types of stressors, and why?

-

4.

How does consumption-induced stress experienced at a certain stage of the decision process affect consumer actions at that stage and at other stages?

-

5.

Can stress be used as an overarching framework to help understand the creation of psychological disequilibria that characterize aversive consumer orientations, such as perceived risk and cognitive dissonance?

Also of interest would be the study of the effects of different consumption-coping responses on a person’s well-being. In general, coping researchers expect problem-focused coping to be more beneficial for well-being than emotion-focused coping, though the evidence is far from conclusive (Thoits 1995). However, there is a widely held belief supported by empirical evidence that problem-focused coping is more effective in reducing or buffering the negative effects of stress on a person’s physical and emotional well-being (Thoits 1995), but under certain circumstances, emotion-focused or secondary control strategies might be functional or beneficial (e.g., Gould 1999; Pavia and Mason 2004). Which specific types of consumption-coping responses are most or least effective in reducing stress, and what is their impact on a consumer’s well-being?

Compulsive consumption, materialism, and consumer well-being are topics of great interest to marketing research for which there is less than adequate theory (e.g., Kwak et al. 2002a, b). Compulsive behaviors, which are often conceived of as addictions to products (e.g., alcohol, drugs, cigarettes), and other excessive or undesirable consumer behaviors (e.g., materialism, gambling, shopping, overspending, shoplifting) have been suggested as possible consequences of coping behaviors used over time to handle stress (e.g., Faber et al. 1987; Hirschman 1992; O’Guinn and Faber 1989). Such consequences, which appear to be related to avoidance-coping strategies (see Table 1), may have adverse effects on a person’s well-being. Consumption avoidance-coping behaviors that succeed in reducing stress provide short-term relief from negative emotional states and enhance a person’s sense of control. Thus, they are likely to be positively reinforced and become conditioned responses to stressful situations. In addition, they may develop into consumption disorders (i.e., events) over time.

Whereas assertions about the development of these orientations have been made in the context of learning theories, the causal processes leading to their development have not been rigorously tested. The relationship between materialism and SWB might be more complex than originally assumed. This relationship might be reciprocal, as Burroughs and Rindfleish’s (2002) study suggested, but the information presented herein suggests that both variables are related to stress in a reciprocal fashion. Thus, further research is needed on the role of stress and specific coping strategies in the development of materialism and SWB.

Finally, there is a need for research on confrontative (primary) and avoidance (secondary) consumption-coping strategies in different cultural settings. Although the concepts of primary and secondary control, which are analogous to problem-focused and emotion-focused, are useful in Western contexts, they break down when viewed from various Asian and other cultural perspectives (Gould 1999). Furthermore, there is substantial evidence to imply that in the East, secondary control strategies might be more effective in buffering the effects of stress, and that such strategies may have more positive effects on a person’s well-being than primary control strategies (Gould 1999). Work in this area would require more careful explication of “collective-oriented” values, as well as the use of specific values (e.g., family, community, religion), because different types of such values may promote the use of different types of coping strategies. In addition, work is needed to assess how specific social-oriented values, such as the values placed on family and community, are related to specific consumption-coping strategies across cultures, rather than inferring their presence or absence in different cultural contexts (e.g., Kwak et al. 2002a, b). Research that addresses the effectiveness of these coping strategies in cross-cultural settings would be particularly helpful in understanding the conflicting cross-cultural findings regarding the relationship between materialism and SWB (Burroughs and Rindfleisch 2002.

References

Andreasen, A. R. (1984). Life status changes and changes in consumer preferences and satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research, 11, 784–794.

Anglin, L. K., Stuenkel, J. K., & Lepisto, L. R. (1994). The effects of stress on price sensitivity and comparison shopping. In C. T. Allen, & D. R. John (Eds.), Advances in consumer research, vol. 21 (pp. 126–131). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

Balkwell, C. (1985). An attitudinal correlate of the timing of a major life event: The case of morale in widowhood. Family Relations, 34, 577–581, (October).

Burroughs, J. E., & Rindfleish, A. (1997). Materialism as a coping mechanism: an inquiry into family disruption. In D. McInnis, & M. Brucks (Eds.), Advances in Consumer Research, vol. 24 (pp. 89–97). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

Burroughs, J. E., & Rindfleish, A. (2002). Materialism and well-being: A conflicting values perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 29, 348–370, (December).

Cohen, L. H. (1988). Life events and psychological functioning. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Duhachek, A. (2005). Coping: A multidimensional, hierarchical framework of responses to stressful consumption episodes. Journal of Consumer Research, 32, 41–53, (June).

Elder, G., Jr., & O’Rand, A. M. (1995). Adult lives in a changing society. In J. S. House, K. Cook, & G. Fine (Eds.), Sociological perspectives on social psychology (pp. 452–475). New York: Allyn & Beacon.

Elder, G., Jr., George, L. K., & Shanahan, M. J. (1996). Psychosocial stress over the life course. In H. B. Kaplan (Ed.), Psychosocial stress: Perspective on structure, theory, life course, and methods (pp. 247–292). Orlando: Academic.

Faber, R. J., Christenston, G. A., De Zwann, M., & Mitchell, J. (1995). Two forms of compulsive consumption: Comorbidity of compulsive buying and binge eating. Journal of Consumer Research, 22, 296–304.

Faber, R. J., O’Guinn, T. C., & Krych, R. (1987). Compulsive consumption. In M. Wallendorf, & P. Anderson (Eds.), Advances in consumer research, vol. 14 (pp. 132–135). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

George, L. K. (1989). Stress, social support, and depression over the life-course. In K. S. Markides, & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), Aging, stress and health (pp. 241–267). New York: Wiley.

George, L. K. (1993). Financial security in later life: The subjective side. Philadelphia: Boettner Institute of Financial Gerontology.

Gierveld, J. J., & Dykstra, P. A. (1993). Life transitions and the network of personal relationships: Theoretical and methodological issues. Advances in Personal Relationships, 4, 195–227.

Gould, S. J. (1999). A critique of Heckhausen and Schulz’s 1995. Life span theory of control from a cross-cultural perspective. Psychological Review, 106(3), 597–604.

Gould, S. J., Considine, J. M., & Oakes, L. S. (1993). Consumer illness careers: an investigation of allergy sufferess and their universe of medical choices. Journal of Health Care Marketing, 13, 34–48, (Summer).

Heatherton, T. F., & Baumeister, R. F. (1991). Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychological Bulletin, 110(1), 86–108.

Heckhausen, J. (2002). Developmental regulation of life course transitions: a control theory approach. In L. Pulkkinen, & A. Caspi (Eds.), Paths to successful development of personality in the life course (pp. 257–280). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heckhausen, J., & Schulz, R. (1995). A life-span theory of control. Psychological Review, 102(2), 284–304.

Hess, R. D. (1970). Social class and ethnic influence upon socialization. In P. Mussen (Ed.), Manual of child psychology, 3rd ed. (pp. 457–559). New York: Wiley.

Hirschman, E. C. (1992). The consciousness of addiction: Toward a general theory of compulsive consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 115–179.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologists, 44(3), 513–524.

Houston, K. B. (1987). Stress and coping. In R. C. Snyder, & C. E. Ford (Eds.), Coping with negative life events. New York: Plenum.

Kagan, J. (1977). The child and the family. Daedalus, 106, 33–56.

Kanner, A. D., Coyne, J., Schaefer, C., & Lazarus, R. (1981). Comparison of two models of stress measurement: Daily hassles and uplifts versus major events. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4(1), 1–39.

Kwak, H., Zinkhan, G. M., & DeLorme, D. E. (2002a). Effects of buying tendencies on attitudes toward advertising. Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising, 24(2), 17–32.

Kwak, H., Zinkhan, G. M., & Dominick, J. R. (2002b). The moderating role of gender and compulsive buying tendencies in the cultivation effects of TV shows and TV advertising: A cross-cultural study between the United States and South Korea. Media Psychology, 4(1), 77–111.

Lazarus, R., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

Lee, E., Moschis, G. P., & Mathur, A. (2001). A study of life events and changes in patronage preferences. Journal of Business Research, 54, 25–38, (October).

Lockenhoff, C. E., & Carstensen, L. L. (2004). Socioemotional selectivity theory, aging, and health: The increasingly delicate balance between regulating emotions and making tough choices. Journal of Personality, 72, 1395–1424, (December).

Luce, M. F. (1998). Choosing to avoid: Coping with negatively emotion-laden consumer decision. Journal of Consumer Research, 24, 409–433, (March).

Madill-Marshall, J. J., Heslop, L., & Duxbury, L. (1995). Coping with household stress in the 1990s: Who uses convenience foods and do they help? In F. R. Kardes, & M. Sujan (Eds.), Advances in consumer research, vol. 22 (pp. 729–734). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

Mathur, A., Moschis, G. P., & Lee, E. (2003). Life events and brand preference changes. Journal of Consumer Behavior, 3(2), 129–141.

McAlexander, J., & Schouten, J. W. (1989). Hair style changes as transition markers. Sociology and Social Research, 75, 58–62.

McAlexander, J., Schouten, J. W., & Roberts, S. D. (1993). Consumer behavior and divorce. In J. A. Costa, & R. W. Belk (Eds.), Research in consumer behavior, vol. 6 (pp. 153–184). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Mergenhagen, P. (1995). Targeting transitions: Marketing to consumers during life changes. Ithaca, NY: American Demographics.

Mick, D. G., & Fournier, S. (1998). Paradoxes of technology: Consumer cognizance, emotions, and coping strategies. Journal of Consumer Research, 25, 123–143, (September).

Miller, N. E., & Dollard, J. (1941). Social learning and imitation. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Monroe, S. M., & Peterman, A. M. (1988). Life stress and psychopathology. In L. H. Cohen (Ed.), Life events and psychological functioning (pp. 31–63). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Moorman, C. (2002). Consumer health under the scope. Journal of consumer research, 29, 152–158, (June).

Moschis, G. P. (1992). Marketing to older consumers. Westport, CT: Quorum.

Norris, F. H., & Murrell, S. A. (1984). Protective function of resources related to life events, global stress, and depression in older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 25, 424–437.

Norris, F. H., & Uhl, G. A. (1993). Chronic stress as a mediator of acute stress: The case of hurricane Hugo. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23(16), 1263–1284.

O’Guinn, T. C., & Faber, R. J. (1989). Compulsive buying: A phenomenological exploration. Journal of Consumer Research, 16, 147–157.

O’Guinn, T. C., & Faber, R. J. (1991). Mass communication and consumer behavior. In T. S. Robertson, & H. H. Kassarjian (Eds.), Handbook of consumer behavior (pp. 349–400). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Pavia, T. M., & Mason, M. J. (2004). The reflexive relationship between consumer behavior and adaptive coping. Journal of Consumer Research, 31, 441–454, (September).

Pearlin, L. I. (1982). Discontinuities in the study of aging. In T. K. Hareven, & K. J. Adams (Eds.), Aging and life course transitions: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 55–74). New York: Guilford.

Pearlin, L. I. (1989). The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 30, 241–256.

Pearlin, L. I., Lieberman, M. A., Managhan, E. G., & Mullan, J. T. (1981). The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22, 337–356.

Reich, J. W., & Zautra, A. J. (1988). Direct and stress-moderating effects of positive life experiences. In L. H. Cohen (Ed.), Life events and psychological functioning (pp. 149–180). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Rindfleish, A., Burroughs, J. E., & Denton, F. (1997). Family structure, materialism and compulsive consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 23, 312–325, (March).

Rothbaum, F., Weisz, J. R., & Snyder, S. S. (1982). Changing the word and changing the self: A two process model of perceived control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42(1), 5–37.

Sanbonmatsu, D. M., & Kardes, F. R. (1988). The effects of physiological arousal on information processing and persuasion. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(3), 379–395.

Schulz, R., & Heckhausen, J. (1999). Aging, culture and control: Setting a new research agenda. The Journals of Gerontology, B, 54(3), 139–145.

Schwartz, B. (2004). The paradox of choice. New York: Harper Collins.

Selye, H. (1956). The stress of life. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Spring, J. (1993a). Seven days of play. American Demographics, 13(3), 50–53.

Spring, J. (1993b). Exercising the brain. American Demographics, 15(10), 56–59.

Stone, A. A., Helder, L., & Schneider, M. S. (1988). Coping with stressful events: Coping dimensions and issues. In L. H. Cohen (Ed.), Life events and psychological functioning (pp. 182–210). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Sujan, M., Sujan, H., & Verhallen, T. M. (1999). Sources of consumers’ stress and their coping strategies. Paper presented at the Association for Consumer Research 1999 European Conference, Joeuy-en-Josas, France, June 24–25.

Tausig, M. (1982). Measuring life events. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 23, 52–64.

Thoits, P. A. (1995). Stress, coping, and social support processes: where are we? What next? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53–79, (Extra Issue).

Turner, J. R., & Avison, W. R. (1992). Innovations in the measurement of life stress: Crisis theory and the significance of event resolution. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 33, 36–50.

Viswanathan, M., Rosa, J. A., & Harris, J. E. (2005). Decision making and coping of functionally illiterate consumers. Journal of Marketing, 69, 15–31.

Wells, W. D. (1993). Discovery-oriented consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 19, 489–504.

Wheaton, B. (1990). Life transitions, role histories, and mental health. American Sociological Review, 55, 209–223.

White, R. W. (1959). Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychological Review, 66, 297–333.

Young, M. M. (1991). Disposition of possessions during role transitions. In R. Holman, & M. Solomon (Eds.), Advances in consumer research, vol.18 (pp. 33–39). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

Zisook, S., Shuchter, S., & Mulvihill, M. (1990). Alcohol, cigarette, and medication use during the first year of widowhood. Psychiatric Annals, 20(6), 318–326.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Anil Mathur, Glen H. Elder Jr., Euehun Lee, Sharon Sullivan, Dena Cox, and the three anonymous JAMS reviewers for their assistance in preparing this paper. The insightful comments of the faculty and doctoral student participants in seminars at Georgia State University, University of Sydney, and the University of Florida are greatly appreciated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moschis, G.P. Stress and consumer behavior. J. of the Acad. Mark. Sci. 35, 430–444 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0035-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0035-3