Abstract

Two common anionic surfactants, sodium oleate (SO) and sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate (SDBS) were used to re-suspend iron oxide nanoparticles in aqueous solutions. At certain SO concentrations, the SO formulations produced highly stable suspensions. In contrast, SDBS-stabilized nanoparticles exhibited poor stability at all concentrations. The adsorption isotherm of SO on iron oxide nanoparticles revealed that stable suspensions were obtained when the equilibrium SO concentration (after adsorption) reached its critical micelle concentration (CMC). At this “optimal” condition, the maximum SO adsorption was reached, and the zeta-potential of the particles was highly negative (~ −50 mV). According to the SO isotherm, this optimal formulation coincided with the formation of a highly compact SO bilayer. The SDBS isotherm, on the other hand, revealed that SDBS is not strongly adsorbed on the surface of iron oxide nanoparticles and that is likely that a patchy, loosely packed bilayer, is formed on the surface of the iron oxide nanoparticles when the equilibrium SDBS concentration reaches its CMC. The DLVO theory confirmed the connection between formulation conditions and the corresponding stability. This works confirmed that the formation of a surfactant bilayer is an important element in producing stable nanoparticle suspensions with anionic surfactants. It was also confirmed that for anionic surfactants, electrostatic repulsions are an important factor in establishing an energy barrier against flocculation. This work also introduced two more elements into the design of nanoparticle suspensions. The first element is that, in order to ensure the best possible dispersion, the surfactant concentration in solution at equilibrium with the adsorbed surfactant should be close or slightly above its CMC. The second element is that the molecular structure of the surfactant should facilitate the formation of closely packed bilayers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Nanoparticles are defined as any particles with dimensions between 1 and 100 nm [1]. Nanoparticles have gained increasing attention in the past decade due to their potential use in cosmetic, pharmaceutical, environmental, and medical applications [2]. One of the key characteristics that make nanoparticles different from other particles is their large surface area relative to their mass [3]. Emerging applications of nanoparticles include their use as dispersed catalysts, and as adsorbents and reactive agents in environmental applications. In all these cases, particle agglomeration produces a reduction in the surface area per unit of mass, and it also increases the chances for settling and attachment to porous media [3].

In the biomedical field, iron oxide nanoparticles have been used in medical diagnostics to enhance the signal of magnetic resonance imaging and in cancer therapies assisted by magnetic fields [4]. Iron oxide particles with 10–100 nm in diameter are optimal for intravenous injection. Particle agglomerates with a diameter higher than 200 nm may decrease blood circulation in certain capillaries [5]. Surface modification can be used to prevent nanoparticle aggregation. Sahoo et al. [6] have reported the surface modification of iron oxide nanoparticles by oleic acid, lauric acid, dodecylphosphonic acid, hexadecylphosponic acid and dihexadecylphosphonic acid in organic solvents. They found that phosphonates could form stable suspensions and suggested the formation of quasi-bilayers on magnetic nanoparticles. Do et al. investigated an in-situ method to stabilize superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles (SPION) using polymers and surfactants [7]. They found that three different types of magnetic colloids can be prepared using biocompatible coating agents: sodium oleate (SO), starch, and methoxypoly(ethylene glycol) (MPEG). SPION coatings were studied by electrokinetic sonic amplitude (ESA), a common method of measuring zeta-potential of colloidal suspensions [7]. In the case of SO-coated SPION, the optimum SO concentration to form a stable suspension corresponds to the maximum ESA value. Bronstein et al. [8] further investigated the complex structure of iron oxide nanoparticles coated by SO. Based on a Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) study, they concluded that the oleate group binds bidentately to iron oxide nanoparticles. Wang et al. [9] prepared iron oxide suspensions in two steps, first adsorbing SO as the first layer, and sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate (SDBS) as the second adsorbed layer. They proposed that the first SO layer is bound to the iron oxide nanoparticles through chemisorptions and that the second layer (SDBS) is bound to the Fe-oleate via physisorption.

Despite the fact that anionic surfactants have been used to suspend iron oxide particles for many years, there is only recent evidence that the formation of anionic surfactant bilayers is involved in the stabilization of magnetite nanoparticles via steric and electrostatic repulsions [10, 11]. These recent findings are incomplete without a framework that would facilitate the selection of the surfactant and its concentration to form stable (i.e. optimal) particle suspensions. This limitation is apparent in the case of nano scale zero valent iron (NZVI) particles. These nanoparticles have a zero valent iron core with an iron oxide shell that makes them, from a colloidal point of view, the equivalent of iron oxide nanoparticles [3]. One article by Saleh et al. [12] compared the stability of NZVI suspensions prepared with various polymers and with SDBS. In the presence of SDBS, the stability of NZVI was relatively low (~30 min) compared to other polymer-based suspensions.

The contrasting observations about the effectiveness of surfactants in preparing stable nanoparticle suspensions illustrate the complexity of selecting the appropriate formulation conditions for surfactant-based nanoparticle suspensions. The objective of this article is to contribute to the development of a framework that connects the molecular structure of the surfactant and its concentration with the properties of the adsorbed surfactant layer and the stability of iron oxide suspensions. To this end, the stability of iron oxide nanoparticle suspensions formulated with SO and SDBS was evaluated in the first part of the results and discussion section. The findings from these studies support the hypothesis that surfactant structure and concentration determine, to a great extent, the properties of the adsorbed surfactant layer and the stability of the suspension. In the next part, the surface activity of each surfactant is evaluated in the presence of particles to assess the adsorption of each surfactant at air/water versus solid/water interfaces. Zeta-potential measurements and DLVO predictions are included in the following part. After that, the adsorption isotherms of SO and SDBS on iron oxide nanoparticles were evaluated as well as the packing density of these surfactants in the absorbed layer. The effects of pH, particle and surfactant concentration on the properties of the suspensions, and the morphology of iron oxide nanoparticles in suspensions are investigated at the end of the section.

Experimental

Materials

Iron oxide nanopowder (Fe3O4, 98 %, product No. 637106, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), oleic acid (90 % technical grade, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate (80 %, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), carboxymethyl cellulose, sodium salt (250 kDa, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and poly(vinyl alcohol-co-vinyl acetate-co-itaconic acid) or PV3A (260 Da, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. Reagent grade sodium hydroxide (pellets, Caledon, Georgetown, ON) was used to prepare a 10 N stock solution to neutralize the oleic acid and produce a sodium oleate (SO) solution in water. 6 N hydrochloric acid (6 N, VWR International, West Chester, PA) was used to dissolve suspended particles for elemental analysis. Deionized (DI, 2 μS/cm) water was used in all aqueous solutions.

Methods

Unless otherwise specified, the procedures describe below were carried out at room temperature (25 °C ± 1 °C).

Nanoparticle Suspensions

To prepare a 30 mM sodium oleate (SO) stock solution, 2.35 grams of 90 % technical grade oleic acid were added to a 250-mL volumetric flask and filled halfway with deionized water. This mixture was stirred at 50 °C to facilitate the initial emulsification of oleic acid. A 10 N NaOH solution was added to the flask slowly until the solution was clear, indicating complete dissociation of oleic acid into sodium oleate. The flask was topped up with deionized water to 250 mL. To prepare the 30 mM SDBS stock solution, SDBS was directly diluted with DI water.

To prepare the suspensions, 0.05 g iron oxide nanoparticles were added to 10-mL of the surfactant solution in 20-mL vials (2.5 cm in diameter × 4.5 cm in height) and vortex-mixed by a Mini Vortexer (VM-3000, Henry Troemner LLC., West Deptford, NJ) at 2,000 rpm for 1 min. Immediately after vortex mixing, the suspension was sonicated using a Sonifier Cell Disruptor (Model W185D, Heat Systems-Ultrasonics Inc., Danbury, CT). The probe of the disruptor was placed into the vial with the tip just above the bottom of the vial and sonicated the mixture at 50 W for 5 min. When necessary, the pH of the solution was adjusted to 10 ± 0.3 using 0.25 N NaOH. The suspension was then decanted into a 15-mL flat-bottom test tube (16 mm external diameter) and capped for further tests.

Particle Stability

Time lapse photography was used to investigate the stability of suspensions as a function of G-force*time. Pictures of the suspensions were taken using a digital camera (C-7070 Wide Zoom, Olympus Imaging Corp., Japan) in a light-controlled environment [13]. The turbidity (τ) was calculated as:

where x = 1.45 cm is the working distance of the cell, I 0 is the intensity of the incident light, and I is the intensity of the transmitted light. The ratio of I 0/I was estimated by measuring the grey level in the middle of a reference 15-mL vial (no iron oxide added, grey level ~ I 0) against a white background, and the grey level in the middle of a sample vial (grey level ~ I). The reference and sample vial were subject to the same illumination intensity (avoiding direct reflection). These grey levels were obtained using the histogram tool of Corel’s Paint Shop Pro (version 9.02) [14]. Each sample was centrifuged using an IEC Clinical Centrifuge (International Equipment Co., Needham Heights, MA) at 2,700 rpm (1150G) in 37.5 min intervals, equivalent to 1G*30 days intervals. Pictures were taken after each 1G*30 days interval.

Adsorption Isotherms on Iron Oxide Nanoparticles

The mass of the surfactants adsorbed on iron oxide nanoparticles was calculated considering the difference in the surfactant concentration in solution before and after adsorption. These surfactant concentrations were measured using a total organic carbon analyzer (TOC-VCPN, Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD). In short, all suspensions were centrifuged using an IEC Clinical Centrifuge (International Equipment Co., Needham Heights, MA) set at 2,100 rpm for 18 h. Aliquots of 3 mL were collected from the top of the centrifuged suspensions and diluted with 6 mL of DI water (3 × dilution) before TOC analysis. The calibration for SO (R 2 = 0.998) and for SDBS (R 2 = 0.999) displayed a linear correlation for concentrations lower than 3 mM of each surfactant.

For SO-stabilized iron oxide nanoparticle suspensions, SO adsorption was also confirmed via surface tension measurements. The surface tension of these aliquots was measured at room temperature (T = 25 ± 1 °C) using a tensiometer (Sigma 700, KSV Instruments, Finland) equipped with a Wilhelmy platinum plate. Each measurement was obtained after 1 min of immersion. The measurement for each sample was repeated 10 times, following consecutive immersions of the Wilhelmy plate into the surfactant solution.

The surface area of the iron nanoparticles was determined using the BET method with N2 as adsorbate. The volumetric adsorption measurements of iron oxide nanoparticles were performed on a surface area analyzer (Autosorb™-1, Quantachrome Instruments, Boynton Beach, FL) [15].

For SDBS-stabilized iron oxide nanoparticle suspension, the adsorption isotherm was confirmed with UV spectrometry using an Ultrospec Plus Spectrophotometer (80-2092-26, LKB Biochrom, England). Briefly, 3 mL of supernatant was collected after centrifuging at 2,100 rpm for 18 h. The absorbance of the samples at the wavelength of 250 nm was recorded.

Zeta-Potential

Zeta-potential was determined using a zeta-potential meter (Delsa 440, Coulter Electronics Inc., Hialeah, FL) using 0.7 mV/cm electric field strength. First 3-mL samples were taken from the suspensions after 24 h settling at 1G, and shaken by hand moments before placing the sample in the measuring chamber.

Iron Content in Suspensions

An Ultrospec Plus Spectrophotometer (80-2092-26, LKB Biochrom, England) was used to determine the iron oxide content. One-milliliter samples were taken from the top of the suspension after 24 h of settling at 1G, and then digested in 15 mL of 6 N HCl in a 30 mL vial for 24 h. After dissolution, the absorbance at 475 nm was recorded. To create a calibration curve, standard samples were made by dissolving known amounts of magnetite nanoparticles in 15 mL of 6 N HCL and 1 mL of deionized water for 24 h. The iron oxide content was calculated based on the calibration curve (R 2 = 0.98) [16]. The iron oxide content was also confirmed by ion coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (Optima 7300, PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA) for selected samples.

TEM Observation

A drop of the suspension (supernatant) obtained after settling for 24 h at 1G was placed on the carbon-coated TEM grid. After applying a vacuum for 10 min, the size and shape of dispersed iron oxide nanoparticles were determined by transmission electron microscopy (HD-2000, Hitachi Ltd., Japan).

Particle Size

The average particle size (hydrodynamic diameter) was determined via dynamic light scattering at a 90° angle, using a BI 90Plus (Brookhaven Instruments, Holtsville, NY, USA) particle size analyzer equipped with a 35-mW diode laser (wavelength ~ 674 nm). To perform the measurements a sample of the suspension (supernatant) obtained after settling for 24 h at 1G was placed in the sample cuvette.

Results and Discussions

Particle Stability

Figure 1 shows pictures of SO and SDBS stabilized iron oxide nanoparticle suspensions after 24 h of preparation. As evidenced by the colour of the suspensions in Fig. 1, SO-stabilized iron oxide suspensions are not stable at low initial (added) surfactant concentrations (i.e. C initial ≤ 1.5 mM), but become stable at higher SO concentrations (C initial > 1.5 mM). However, unlike SO suspensions, SDBS suspensions are unstable at all SDBS concentrations. These observations support the inconsistencies in the literature about the stability of surfactant-based nanoparticle suspensions [6, 7, 12] and illustrate the need for a formulation framework that defines the appropriate surfactant structure and concentration to produce stable suspensions.

While the purpose of this work was to advance the framework for designing surfactant-stabilized nanoparticles, it is important to compare the stability observed in Fig. 1 to the stability of nanoparticles in polymer solutions, which are commonly reported in the literature [4, 7, 12]. Saleh et al., for example, determined that while the stability of NZVI re-suspended with SDBS is approximately 30 min (consistent with Fig. 1), the stability obtained with tri-block copolymers could be closer to 2 h. More stable NZVI suspensions have been produced with solutions of sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (SCMC) and poly(vinyl alcohol-co-vinyl acetate-co-itaconic acid), also known as PV3A, when these polymers were added during the preparation of the nanoparticles [17, 18]. In the case of PV3A, it has been claimed that NZVI-PV3A suspensions can be stable for several months [18].

Figure 2 shows a picture of iron oxide suspensions prepared with SCMC and PV3A using formulation conditions identified as optimal for NZVI suspensions [17, 18]. These polymer solutions were not able to form stable suspensions (after 24 h) of iron oxide nanoparticles. This observation suggests that although these polymers were useful in forming protective coatings around single nanoparticles during synthesis, they are not able to penetrate nanoparticle agglomerates and overcome the interaction among neighbouring nanoparticles.

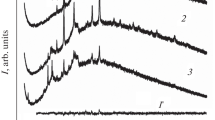

To further characterize the long-term stability of SO-stabilized nanoparticles, pictures of the samples and blank (no nanoparticle) test tubes were taken over several weeks under controlled lighting against a white background. The turbidity of the samples was estimated using the ratio of gray levels obtained in the middle of the vial as described above. It is important to clarify that the estimated turbidity was only used to normalize the image analysis data and that the proportionality between the estimated turbidity and the concentration of the nanoparticles is questionable in highly concentrated suspensions [13]. Figure 3 summarizes the values of the estimated turbidity for different SO formulations as a function of G-force* time. Compared to other formulations, the turbidity of the 3 mM SO suspension shows little change (form 1.1 to 0.7 cm−1) after 150 G* days, which simulates 5 months of storage. It is relevant to mention that samples of 3 mM SO-nanoparticles stored at 1G have been stable for more than 6 months. In the 6 mM SO formulation, the estimated turbidity remains close to that of the 3 mM solution, suggesting that particle bridging might not be a significant issue at high SO concentrations. The particle bridging phenomenon can take place at high surfactant concentrations when surfactant micelles or dissolved surfactant monomers fuse the surfactant bilayers of neighbouring particles, leading to particle agglomeration [19]. Lee et al. [19] hypothesized that this effect could explain the instability of nanoparticle suspensions produced with high concentrations of SDBS.

Surface Activity of SO and SDBS

The critical micelle concentration (CMC) of SO was determined from the plot of surface tension versus surfactant concentration (results not shown). For SO, the surface tension of the system is approximately constant at concentrations larger than 0.9 mM; suggesting that 0.9 mM (at pH = 10) is the CMC of SO. This CMC is larger than the CMC reported by Theander et al. [20] at pH = 10 of 0.1 mM. The difference in CMC is due to the high ionic strength (100 mM) of the sodium oleate solutions used by Theander et al. [20]. Zhang et al. [21] reported a similar value of 1.1 mM at pH = 10 under low ionic strength. The CMC for SDBS system was 1.5 mM, similar to the reported value (1.3 ± 0.5 mM) by Segota et al. [22].

The relation between surface tension and SO concentration below the CMC can be used to estimate surface excess concentration (Γ) and the area per molecule (a s) of the surfactant using the Gibb’s adsorption isotherm [23]:

where C is the surfactant concentration; R is the universal gas constant; T is absolute temperature; n = 1 for dilute solutions containing nonionic surfactant and n = 2 for the dilute solutions containing ionic surfactant (n = 2 for this case). The surfactant area per molecule (a s) can be calculated as:

According to this equation, the area per molecule of SO was 42 Å2, larger than the value 26 Å2 (pH = 10, 100 mM ionic strength) reported by Theander et al. [20]. This is possibly due to the low ionic strength in our solution conditions, which results in the increased repulsion force between head groups of SO monomers and decreased adsorption of SO at air/water interface (e.g. increased area per molecule of SO) [23]. Another study showed the area per molecule of SO is 52 Å2 under pH = 10 and low ionic strength [21], slightly higher than our value. The area per molecule of the SDBS was 88 Å2, slightly larger than the range of values reported by Segota et al. [22] (60–80 Å2).

Figure 4 shows the surface tension isotherms of SO and SDBS in the presence of iron oxide nanoparticle suspensions at pH = 10. In solutions of polymers and surfactants, these types of surface tension isotherms are used to evaluate the binding of surfactants to polymers [24]. Here, these isotherms are useful to assess the adsorption of SO and SDBS to iron oxide nanoparticles. The surface tension isotherm for SO on iron oxide nanoparticles presents two breaks: the first break at the plateau region at C initial = 0.7 mM (C equilibrium ~ 0.2 mM), corresponding to the critical aggregation concentration (CAC) and the second break at C initial = 3.3 mM (C equilibrium = 0.9 mM), corresponding to the CMC. At the CAC the surfactant may begin to form admicelles on the surface of the nanoparticles [23]. For the SO-nanoparticle system, SO adsorbs on nanoparticles likely due to ion exchange (exchange of OH− by R–COO− ions on the surface of iron oxide nanoparticles) at pH = 10. The difference in surfactant concentration between CAC and CMC depends on the amount of iron oxide nanoparticles. The second plateau in surface tension is observed when micelles form in solution. This is the CMC for the surfactant. Beyond the CMC, the surfactant adsorption stops and any increase in surfactant concentration results in the formation of micelles [25]. In the case of SDBS, the CAC and CMC transitions are less defined suggesting that the surfactant preferentially adsorbs at the air–water interface (lower surface tensions than SO), and a smaller fraction of the surfactant may adsorb on the nanoparticles.

Zeta-Potential and DLVO Theory

The zeta-potential of SO and SDBS nanoparticle suspensions is shown in Fig. 5. For the SO-nanoparticle system, the zeta-potential shifted towards more negative values with increasing surfactant concentration (for C equilibrium < CMC), which is compatible with the idea that surfactant adsorption takes place even at low surfactant concentrations. Above the CMC, the zeta-potential shows marginal change and remains around −50 mV, possibly suggesting that little or no adsorption takes place. Paruchuri et al. [26] suggested that the zeta-potential value of the surfactant-covered graphite surface at C equilibrium ≥ CMC represents the zeta-potential of the surface micelles by comparing their results with the zeta-potential value of micelles formed in bulk solution. Therefore, it is noted that the appearance of micelles at C equilibrium > CMC may interfere the zeta-potential measurement. For the SDBS-nanoparticle system, the zeta-potential also shifts towards more negative values and reaches a plateau value of -40 mV at C initial = 2.4 mM, indicating that SDBS is adsorbed on to the iron oxide nanoparticles at C initial ≤ 2.4 mM. Similar to the SO-nanoparticles system, very little or no SDBS adsorption takes place on the iron oxide nanoparticles above this concentration.

It is possible to predict the energy barrier for particle flocculation at different SO and SDBS concentration using the DLVO theory. Based on this theory, the total potential energy of interaction V is the sum of the potential energy of attraction V A and the potential energy of repulsion V R [23]:

where V A is the attraction energy due to van der Waals interaction. For the particle–particle interaction, it can be calculated based on the following equation [23]:

In Eq. (5), A effective is the effective Hamaker constant and can be estimated using Eq. (5a). H is the distance between two particles; “a” is the radius of the iron oxide particles [23]. In the calculation, a is estimated as 25 nm based on the manufacturer information.

V R is the repulsion energy due to electrostatic interactions, as calculated using the following Eq. [23]:

where εr is the dielectric constant of water; ε0 is the vacuum permittivity; ζ is the zeta-potential value;. κ is the inverse value of the Debye length; calculated as [23]:

where N A is Avogadro’s number; e is the charge of the electron; k is the Boltzmann constant; c i is the aqueous concentration of the sodium group (Na+) and carboxylic group (C17H33COO−) of the surfactant respectively; Z i is the valence of the sodium group (Na+) and the carboxylic group (C17H33COO−) of the surfactant respectively; T is the temperature. A summary of the parameters used for DLVO prediction is shown in Table 1.

The energy barrier for flocculation at different SO and SDBS concentrations can be estimated by plotting the total potential energy of interaction V versus the separation between the particles; H. Figure 6 illustrates the interaction potential (V) profile at different SO and SDBS concentrations. The energy barrier for flocculation increases as the magnitude of the zeta-potential increases. It has been estimated that an energy barrier for flocculation greater than 15 kT is necessary to produce stable suspensions [23]. As shown in Fig. 6, an energy barrier larger than 15 kT is obtained with the SO system at CMC (corresponding to C initial = 3 mM), which is consistent with the formation of stable SO-coated iron oxide nanoparticles suspensions.

One of the DLVO prediction limitations is the neglect of nonelectrical steric barrier to aggregation. This barrier especially plays an important role in stabilizing nanoparticles for the surfactants that are polymeric or have long polyoxyethylene (POE) chains [23]. Therefore, the adsorption isotherms and packing density were investigated to fully understand the stability of SO-coated iron oxide nanoparticle suspension.

Adsorption Isotherms and Packing Density

The surfactant adsorption on iron oxide nanoparticles (q) was calculated as follow:

where m nanoparticles is the total amount of iron oxide nanoparticles in the mixture (mass of adsorbent, 0.05 g in this study); C initial and C equilibrium are the initial and equilibrium surfactant concentrations respectively. These concentrations were quantified via TOC measurements. V is the total volume of the suspensions (10 mL). M is the molecular weight of the surfactant; q is defined as a dimensionless ratio of the mass of surfactant adsorbed on the nanoparticles to the mass of nanoparticles. Figure 7 shows the relationship between q and C equilibrium for the SO-nanoparticles system.

The adsorption isotherm of Fig. 7 was divided into 4 regions, corresponding to the regions proposed by Scamehorn et al. [25] for the adsorption of anionic surfactants on metal oxides. Region 1 corresponds to the adsorption of surfactant monomers on the iron oxide nanoparticles via ion exchange. Region 2 corresponds to the self-assembly, via lipophilic interactions of surfactants to form admicellar structures. In region 3, surfactant adsorption is less favorable because the surfactant assembly is crowded and ionic and steric repulsion among neighbouring surfactants hinder the adsorption process. Region 4 corresponds to the completion of the adsorption process when C equilibrium reaches or surpasses the CMC of the surfactant. All regions are clearly shown in Fig. 7.

In principle, it is possible to combine the surface tension isotherms of Fig. 4 for the SO-nanoparticle system and the surface tension isotherm of SO in water to estimate the final concentration of SO and the adsorption isotherm. This procedure leads to an adsorption isotherm for SO that produced similar q and C equilibrium values (data not shown) for regions 3 and 4 as those presented in Fig. 7. Furthermore, the value of the CAC (~0.2 mM at equilibrium) estimated from the data in Fig. 4 is consistent with the onset of admicelle formation in region 2, as shown in Fig. 7. Since that the TOC measurement represents a more direct evaluation of the final surfactant concentration, only the TOC method was reported.

The TOC method was used to obtain the adsorption isotherm of SDBS-iron oxide. The adsorption isotherm was also confirmed using absorbance values at a wavelength of 250 nm (data not shown). Figure 8 presents a comparison of the adsorption isotherms of SO and SDBS on iron oxide nanoparticles.

It is evident from Fig. 8 that more SO is adsorbed on the iron oxide nanoparticles at the plateau region (region 3) than SDBS. This suggests that SO molecules pack more efficiently than SDBS on the surface of the nanoparticle. Heinz et al. [27] proposed a way to calculate the packing density of adsorbed molecules (λ):

where a c is the average cross-sectional area per alkyl chain (for C–C backbone, a c = 18.8 Å2 [27]) and a s, solid is the area occupied per molecule of surfactant at solid/water interface. At CMC, a s, solid can be calculated based on Eq. (9):

where M and N were as defined above. The specific surface area (S s = 47 m2/g) of iron oxide was determined using the BET technique. q CMC is the amount of surfactant adsorbed on iron oxide nanoparticles when C equilibrium reaches the CMC (the onset of region 4 in Fig. 7). Based on the TOC-results, the surface area occupied per molecule of surfactant at the solid/water interface (a s, solid) was 20 Å2 for SO and 59 Å2 for SDBS at CMC. a c = 18.8 Å2 for SO and a c = 18.8 × 2 = 37.6 Å2 for SDBS (due to the existence of two alkyl chains per SDBS molecule). Table 2 presents a summary of these parameters. The packing density of SO and SDBS were 0.95 and 0.64 respectively, suggesting that a very compact SO layer was formed on iron oxide nanoparticles, and that a loosely packed SDBS layer was formed on iron oxide nanoparticles.

Another way to quantify the packing density of SO and SDBS is by calculating the number of theoretical coating layers (n) as follows:

where a s is the area per molecule of surfactant at the water/air interface, as defined in Eq. (3). The surface area per molecule of SO and SDBS (a s) calculated from Gibbs adsorption equation were 42 and 88 Å2/molecule, respectively. From Eq. (10), n = 2.1 for SO and n = 1.5 for SDBS at CMC. Similar to the conclusions made by Wang et al. [9], these calculations suggest that SO forms a compact bilayer on iron oxide nanoparticles at CMC. However, for SDBS a value of n = 1.5 could represent a mixture of a monolayer and a bilayer, or a patchy and loosely packed bilayer. The fact that the magnitude of the zeta-potential for SDBS-nanoparticle systems increases with increasing SDBS concentration (Fig. 5), even at low SDBS concentration, suggests the formation of negatively, although loosely packed, charged bilayers.

Effect of pH, and Surfactant and Iron Concentration on Suspension Properties

Figure 9 presents the concentration of iron oxide suspended in the aqueous solution after 24 h of settling as a function of the initial SO concentration. Figure 9 also presents the average particle size for the suspended particles in SO solutions. Increasing the SO concentration towards C equilibrium = CMC increases the fraction of iron oxide suspended and reduced the particle size of the system. Above the CMC, the concentration of iron oxide suspended is slightly reduced with the addition of SO. While the turbidity data at 6 mM SO did not show any effect of particle bridging, the data at 10 mM suggest a minor influence of the particle bridging effect [19].

A common topic throughout this work is that particle charge is important in determining the stability of the suspension. This charge is influenced by the pH of the suspension. Figure 10 shows the effect of pH on the concentration of iron oxide in suspension. A reduction in pH towards acidic environments (e.g. pH = 3) produced a reduction in the suspended iron concentration. This reduction in suspended iron concentration in acidic environments could be explained by the dissociation of the carboxylic group of the oleic acid. Considering that the pKa of oleic acid is 5.02 [28], then at pH values near 5 or below, the carboxylic group exists in its neutral (protonated) state as oleic acid (C17H33COOH), which does not produce a charged layer on the particles. In fact, the formation of protonated oleic acid coating on the particle could lead to the aggregation of particles since oleic acid itself is not highly soluble in water. There was some evidence as to the formation of unstable and hydrophobic iron oxide nanoparticles for systems with pH < 5, in the form of non-wettable particles that tend to float on the surface of the liquid.

With the increase in pH (e.g. pH > pKa), the carboxylic group of SO dissociates, becoming negatively charged (in C17H33COO− form at pH > pKa). As a result of oleate ions adsorption, and the formation of a double layer, more iron oxide nanoparticles are suspended due to electrostatic repulsions. At high pH (e.g. pH = 12), the concentration of OH− ions is relatively high and it is conceivable that it interferes with the ion exchange of SO on the surface of iron oxide nanoparticles [29]. As a consequence of this competitive adsorption/ion exchange, an optimal pH exists to obtain highly concentrated surfactant-nanoparticle suspensions (e.g. pH = 10 for 3 mM SO-coated iron oxide nanoparticle).

The initial particle concentration can also impact the fraction of suspended iron oxide nanoparticles. As shown in Fig. 11, the concentration suspended iron oxide nanoparticles (m Fe3O4) increased with the increase of initial particle concentration (m Fe3O4, initial). However, it is important to interpret this information in terms of the fraction of particles suspended:

According to Fig. 11, all the particles can be suspended, for a period of 24 h, up to a concentration of 2 g/L. After that concentration, the fraction of particles suspended decreases slightly with increasing total iron oxide concentration in the system. This decrease may be attributed to the increase in collision probability with increasing particle concentration [30]. He et al. [31] reported similar results. They found the aggregation rate of hematite nanoparticles increased with increasing particle concentration, which resulted in a faster growth of particle aggregates.

Morphology of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles

Figure 12 presents a TEM micrograph of an iron oxide nanoparticle suspension prepared with 3 mM SO. In this micrograph, the particles are present in loosely associated agglomerates ranging from 10 to 200 nm, consistent with the data of Fig. 9 for 3 mM SO suspensions. The grey regions surrounding the particles are likely associated with surfactant deposits formed after water was evaporated in the TEM chamber (vacuum conditions). Suspensions prepared with 0.9 mM SO produced larger and more compact aggregates (not shown). Suspensions prepared with less than 0.9 mM SO were too unstable to obtain a representative sample.

References

Lechner MD, Machtle W (1999) Characterization of nanoparticles. Macromol Symp 145:1–7

Aitken RJ, Chaudhry MQ, Box ABA, Hull M (2006) Manufacture and use of nanomaterials: current status in the UK and global trends. Occup Med 56:300–306

Tratnyek PG, Johnson RL (2006) Nanotechnologies for environmental cleanup. Nanotoday 1:44–48

Gupta AK, Gupta M (2005) Synthesis and surface engineering of iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Biomaterials 26:3995–4021

Laurent S, Forge D, Port M, Roch A, Robic C, Elst LV, Muller RN (2008) Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: synthesis, stabilization, vectorization, physicochemical characterizations, and biological applications. Chem Rev 108:2064–2110

Sahoo Y, Pizem H, Fried T, Golodnitsky D, Burstein L, Sukenik CN, Markovich G (2001) Alkyl phosphonate/phosphate coating on magnetite nanoparticles: a comparison with fatty acids. Langmuir 17:7907–7911

Kim DK, Mikhaylova M, Zhang Y, Muhammed M (2003) Protective coating of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Chem Mater 15:1617–1627

Bronstein LM, Huang X, Retrum J, Schmucker Q, Pink M, Stein BD, Dragnea B (2007) Influence of iron oleate complex structure on iron oxide nanoparticle formation. Chem Mater 19:3624–3632

Wang X, Zhang C, Wang X, Gu H (2007) The study on magnetite particles coated with bilayer surfactants. Appl Surf Sci 253:7516–7521

Shen L, Laibinis PE, Hatton TA (1999) Bilayer surfactant stabilized magnetic fluids: synthesis and interactions at interfaces. Langmuir 15:447–453

Hajdú A, Tombácz E, Illés E, Bica D, Vékás L (2008) Magnetite nanoparticles stabilized under physiological conditions for biomedical application. Prog Coll Polym Sci 135:29–37

Saleh N, Sirk K, Liu Y, Phenrat T, Dufour B, Matyjaszewski K, Tilton RD, Lowry GV (2007) Surface modifications enhance nanoiron transport and NAPL targeting in saturated porous media. Environ Eng Sci 24:45–57

De Sena RC, Soares M, Pereira MLO, Da Silva RCD, Do Rosário FF, Da Silva JFC (2011) A simple method based on the application of a CCD camera as a sensor to detect low concentrations of barium sulfate in suspension. Sensors 11:864–875

Yuan J, Yip A, Nguyen A, Chu J, Wen X, Acosta EJ (2010) Effect of surfactant concentration on transdermal lidocaine delivery with linker microemulsions. Int J Pharm 392:272–284

Brunauer S, Teller E (1938) Adsorption of gases in multimolecular layers. J Am Chem Soc 60:309–319

Jakobik-Kolon A, Skwira M (2011) Determination of fluoride ions in iron ores by UV–VIS spectrophotometry after matrix removal using Diphonix® resin. Geostand Geoanal Res. doi:10.1111/j.1751-908X.2011.00128.x

Sakulchaicharoen N, O’Carroll DM, Herrera JE (2010) Enhanced stability and dechlorination activity of pre-synthesis stabilized nanoscale FePd particles. J Contam Hydrol 118:117–127

Sun YP, Li XQ, Zhang WX, Wang HP (2007) A method for the preparation of stable dispersion of zero-valent iron nanoparticles. Colloids Surf A 308:60–66

Lee HH, Yamaoka S, Murayama N, Shibata J (2007) Dispersion of Fe3O4 suspensions using sodium dodecylbenzene sulphonate as dispersant. Mater Lett 61:3974–3977

Theander K, Pugh R (2001) The influence of pH and temperature on the equilibrium and dynamic surface tension of aqueous solutions of sodium oleate. J Colloid Interface Sci 239:209–216

Zhang Z, Li F, Friberg SE, Aikens PA (2000) Emulsions, foams, and thin films. In Mittal KL, Kumar P (eds) pp 463–480

Segota S, Heimer S, Tezak D (2006) New catanionic mixtures of dodecyldimethylammonium bromide/sodium dodecylbenzenesulphonate/water I. Surface properties of dispersed particles. Colloids Surf A 274:91–99

Rosen MJ (2004) Surfactants and interfacial phenomena, 3rd edn, pp 60–64, 82, 336–337

Claesson PM, Makuska R, Varga I, Meszaros R, Titmuss S, Linse P, Pedersen JS, Stubenrauch C (2010) Bottle-brush polymers: adsorption at surfaces and interactions with surfactants. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 155:50–57

Scamehorn JF, Schechter RS, Wade WH (1982) Adsorption of surfactants on mineral oxide surfaces from aqueous solutions: III. Binary mixtures of anionic and nonionic surfactants. J Colloid Interface Sci 85:494–501

Paruchuria VK, Nguyenb AV, Millera JD (2004) Zeta-potentials of self-assembled surface micelles of ionic surfactants adsorbed at hydrophobic graphite surfaces. Colloids Surf A 250:519–526

Heinz H, Vaia RA, Farmer BL (2008) Relation between packing density and thermal transitions of alkyl chains on layered silicate and metal surfaces. Langmuir 24:3727–3733

John H, Schlegel W (1999) Determination of the pK a of 12-S-hydroxyheptadecatrienoic acid by studies of its vial surface adsorption using high-performance liquid chromatography and liquid scintillation technique. Chem Phys Lipids 99:95–101

Xu X, Yu Z, Zhu Y, Wang B (2005) Effect of sodium oleate adsorption on the colloidal stability and zeta-potential of detonation synthesized diamond particles in aqueous solutions. Diamond Relat Mater 14:206–212

Kretzschmar R, Holthoff H, Sticher H (1998) Influence of pH and humic acid on coagulation kinetics of kaolinite: a dynamic light scattering study. J Colloid Interface Sci 202:95–103

He YT, Wan J, Tokunaga T (2008) Kinetic stability of hematite nanoparticles: the effect of particle sizes. J Nanopart Res 10:321–332

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). The authors are thankful to the research groups of Professors Charles Jia and Professor Ramin Farnood of the Department of Chemical Engineering and Applied Chemistry at the University of Toronto for their assistance with the BET and Zeta-potential measurement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Lam, A. & Acosta, E. Suspensions of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Stabilized by Anionic Surfactants. J Surfact Deterg 16, 397–407 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11743-012-1425-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11743-012-1425-1