Abstract

The increasing number of elderly persons produces an increase in emergency department (ED) visits by these patients, including nursing home (NH) residents. This trend implies a major challenge for the ED. This study sought to investigate ED visits by NH residents in an academic hospital. A retrospective monocentric analysis of all ED visits by NH residents between 2005 and 2010 in a Swiss urban academic hospital. All NH residents aged 65 years and over were included. Socio-demographic data, mode of transfer to ED, triage severity rating, main reason for visit, ED and hospital length of stay, discharge dispositions, readmission at 30 and 90 day were collected. Annual ED visits by NH residents increased by 50 % (from 465 to 698) over the study period, accounting for 1.5 to 1.9 % of all ED visits from 2005 to 2010, respectively. Over the period, yearly rates of ED visits increased steadily from 18.8 to 27.5 per 100 NH residents. Main reasons for ED visits were trauma, respiratory, cardiovascular, digestive, and neurological problems. 52 % were for urgent situations. Less than 2 % of NH residents died during their ED stay and 60 % were admitted to hospital wards. ED use by NH residents disproportionately increased over the period, likely reflecting changes in residents and caregivers’ expectations, NH staff care delivery, as well as possible correction of prior ED underuse. These results highlight the need to improve ED process of care for these patients and to identify interventions to prevent potentially unnecessary ED transfers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Population ageing, resulting from the combined effect of increased life expectancy and decreased birth rate, is a major public health and economic concern in western countries [1, 2]. In US and European hospitals, the increased absolute number of persons aged 65 years and over produces an increase in emergency department (ED) visits by these patients [2, 3]. This trend implies a major challenge for the ED in the context of scarce resources and limited specific skills of emergency professionals in caring for this population [3, 4]. Simultaneously, a disproportionate increase in ED visits for nursing home (NH) residents has been described [5, 6].

According to some authors, a large proportion of these ED visits by NH residents is potentially preventable and even judged inappropriate [7, 8]. Transfers of these residents to acute care hospitals should therefore be carefully studied to understand the health care needs of these patients, and to implement dedicated strategies to address most adequately these needs. If numerous studies have been conducted in the USA, Australia or Canada, less information is available on ED visits for NH residents in European settings.

This study sought to investigate the evolution over time of the number of ED visits by NH residents in a Swiss academic medical center, and to describe these ED visits (i.e., mode of admission, schedule, triage level, main reason for visit), as well as their outcomes (i.e., length of ED and hospital stay, ED and hospital discharge dispositions).

Methods

Setting and study participants

This study is a descriptive, retrospective analysis of all ED visits by NH residents aged 65 years and over (65 + y) that occurred between 2005 and 2010 at the Lausanne University Hospital in Lausanne, a Swiss urban area. The Lausanne University Hospital is a 1500-bed public university hospital that provides primary care for the 300,000 inhabitants of the Lausanne area, as well as tertiary care for Western Switzerland (about 1.5 million population area). The hospital functions as the first-level community hospital for approximately 60 nursing homes.

Patients in Switzerland have access to office-based physicians in an ambulatory care setting, unless they are insured with managed care organizations with gatekeeper systems. General practitioners and accredited primary care physicians are on call for the majority of the NH institutions. Access to the ED is essentially unlimited. The ED at Lausanne University Hospital receives approximately 55,000 adult patients per year, initially evaluated by triage nurses. Many patients (~20,000) are admitted for specialized health problems (ophthalmology, gynecology, psychiatry, etc.) and thus referred from the ED to these specialized clinics or to the ambulatory primary care clinic of the hospital. These outpatients are not included in this study. The remaining patients (~35,000 patients/year) are admitted and treated in the ED, and were eligible for this study.

The prehospital emergency medical service (EMS) has a unique emergency dispatch center, using a specific keyword-based dispatch protocol. Trained paramedics or emergency medical technicians constitute the initial response on site. Prehospital emergency physicians may be dispatched on scene in the case of cardiac arrest, major trauma, respiratory distress, or other life-threatening emergencies; or secondary at the request of the paramedics on site.

Data sources

Data were collected and recorded in a specific de-identified anonymous database including all elderly persons aged 65 years and over who visited the ED from year 2005 to 2010. This database was created by merging two administrative databases named AXYA (hospital’s information database) and Gyroflux (ED patient’s flow database), as described in a previous publication [4]. Overall, 98 % of ED visits registered in the two databases could be matched through the patient’s and stay’s identification numbers. Demographic data for the overall state population and for the NH residents living in the area of Lausanne between 2005 and 2010 were obtained from the statistical office of the State of Vaud.

The study was approved by the State Authorities and by the Lausanne University Ethics Committee. Because of the retrospective nature of this research and its anonymity, the study did not require personal information or explicit agreement of the patients. Patients admitted at the Lausanne University Hospital received systematic information about the use of de-identified anonymous data for the purpose of retrospective studies.

Measures

All ED visits by NH residents aged 65 + years that occurred between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2010, were included in the study. The incidence rates for ED visits and evolution over the period were estimated based on the total number of NH beds in the corresponding fiscal year, taking into account the occupation rate of these beds in the Lausanne area. The number of admissions of NH residents in the ED was evaluated according to the total number of patients admitted annually in the ED. To calculate rates of ED use per NH residents, we used resident-year denominators based on the number of NH beds in the corresponding fiscal years.

Variables considered in the analysis were age, gender, mode of admission (ambulance, walk-in, ambulance with prehospital emergency physician), date and time of ED arrival and discharge, main reason for ED visit and triage level (according to the Swiss Triage scale, see below), disposition at ED discharge (nursing home, hospital admission, death, other), at hospital discharge (nursing home, death, other), and readmission to ED within 30 and 90 days after ED discharge. Length of ED stay in hours (mean and standard deviation) was calculated as the difference between the date and time of arrival at, and discharge from, the ED.

Reasons for ED visit (presenting chief complaints) and triage level are assessed on arrival using a local triage scale. Until late 2009, the ED used a local 115 items, previously validated, triage scale (Lausanne triage and priority scale) [9]. This scale comprised five triage levels (1–5), reflecting the time delay before the patient had to be medically evaluated. In 2010, the Lausanne scale was replaced by the four-level Swiss Triage Scale (STS, 92 items and 4 triage levels). Triage category 1 (patient requiring immediate medical evaluation) and 2 (patient requiring evaluation within 20 min) are considered as urgent. These two categories were not affected by the changes in the triage scale. Semi-urgent category 3 (patient requiring evaluation within 120 min) and category 4 (non urgent conditions) complete the STS [10]. Each patient is assigned a triage category based on the presumed urgency of the case.

For clarity, the 115 reasons for ED visit recorded from the Lausanne triage and priority scale were aggregated into groups, and only the first three most frequent groups were depicted. ED readmission at 30 and 90 day after discharge was identified using the patient’s ID number. ED readmission rate was calculated for the entire study period.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated, using median and inter-quartile range. Differences in continuous variables were assessed using Spearman test and Kruskal–Wallis test because of non-normally distributed data. Differences in proportions were analyzed using Chi-squared test. In all analyses, differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05 (two-tailed). All analyses were performed using Stata 13.1 [11].

Results

Between 2005 and 2010, the overall number of ED visits at Lausanne University Hospital increased from 30,487 to 36,704 (+20.3 %); excluding visits from patients referred to ambulatory clinics (see “Methods” section). Over the same period, visits by NH residents increased by 50.1 % (from 465 to 698), accounting for 1.5 % of all ED visits in 2005 and 1.9 % in 2010. As the number of NH beds in the Lausanne area increased only marginally (+2.5 %, from 2476 to 2539) (Table 1), rate of ED visits per NH beds increased progressively and disproportionately from 18.8 to 27.5 visits per 100 NH beds per year (+46.4 %, p < 0.01) (Fig. 1). The proportion of ED visits by NH residents over the total number of visits for patients aged 65 and over (community-dwelling older persons and NH residents) significantly increases over the period (5.6–6.7 %, p < 0.01).

NH residents visiting the ED were mostly women (65.5 % of all NH resident visits). Mean age over the study period was 84.3 ± 8.4 years, and appeared quite stable (from 83.7 ± 7.6 to 84.3 ± 8.4 years in 2005 and 2010, respectively, p = 0.26) despite a significant increase in the proportion of residents aged ≥85 years and over (from 49 to 53 % between 2005 and 2010, p = 0.02).

The mode of admission was unknown in 18.9 % of the NH residents. Among the others, more than two-thirds were transferred from the NH to the ED with an ambulance, without requiring a prehospital emergency physician (Table 1), a proportion that increased significantly over the study period (from 69.1 % in 2005 to 71.4 % in 2010, p = 0.003). However, when considering all NH residents transferred with an ambulance, i.e., with and without an emergency physician onboard, this overall proportion remained stable over time.

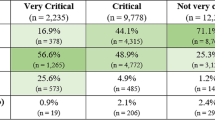

The top-five reasons for ED visits were injury, respiratory problems, cardiovascular problems, digestive problems and neurological problems. These top-five reasons remained the same over the study period even though there were slight variations in their ranking (Table 1). Fever appeared only in about 6.3 %. The proportion of severe cases remained unchanged over the period, with a proportion of urgent situations of 51.9 % (STS 1 and 2 representing 14.6 and 37.3 % of the cases, respectively).

The hourly distribution of ED visits remained stable over the study period (Fig. 1), with a large majority of the residents visiting during the 7 am–2 pm period (51.8 %) and the 2 pm–10 pm period (39.3 %). Residents visiting late at night (10 pm–7 am) were only a minority (8.9 %). This distribution is strikingly similar to the schedule of visits observed among community-dwelling elderly persons who visited the ED over the same study period (Fig. 2).

The distribution over the days of the week also remained stable between 2005 and 2010. A non-significant predominance of admissions on Thursday (15.8 %) and Friday (15.7 %), as well as lower rates of visits during Saturday (13.0 %) and Sunday (12.1 %) were observed. Again, this distribution was indistinguishable from that observed in community-dwelling older persons.

Finally, seasonal distribution showed a slight predominance of visits in autumn (October–December 27.7 %,) compared to summer (July–September 25.7 %), spring (April–June 23.1 %) or winter (January–March 23.5 %).This distribution was similar to the one observed among community-dwelling older ED patients.

Median ED length of stay (LOS) was 6.5 h (inter-quartile range, IQR 3.9–20.3) for patients discharged directly from the ED (Table 2). This ED LOS did not differ according to age and was similar to the LOS for non-NH patients of similar age. Only a very small proportion of the NH residents died in the ED (N = 50, death rate 1.4 %). Most (58.0 %) were admitted to the acute care hospital, whereas about a third (37.6 %) returned to their NH. These proportions did not change over the study period. However, the proportion of NH residents discharged directly to their NH after the ED visit was higher in 2009 and 2010 than in 2007 and 2008. Readmission at 30 and 90 day in residents directly discharged from ED to their NH occurred in 9.7 and 19.6 %, respectively. Only readmission rate within 90 days significantly increased over the study period (15.2–22.6 % from 2005 to 2010, p < 0.01).

Among NH residents admitted to the acute hospital, median ED LOS was 9.5 h (IQR 5.3–24.8). Their subsequent hospital median LOS was 9.0 days (IQR 4.0–15.0). This hospital LOS was similar to the hospital LOS for non-NH patients aged 65 and over. The majority (56.2 %) of admitted NH residents returned to their NH after their acute stay, an additional 4.5 % were admitted to rehabilitation, and 2.3 % were further transferred to geropsychiatric hospital. Death rate during the hospitalization was only 8.7 % (N = 195). Data were not available in 28.3 %. Readmission rate was 6.4 % at 30 day, and 15.6 % at 90 day. Again, only the readmission rates at 90 day significantly increased over the study period (from 11.7 % in 2005 to 17.8 % in 2010, p < 0.01). Main reasons for readmission were injuries (17.1 %) and respiratory conditions (17.5 %).

Compared with NH residents hospitalized, patients discharged back to their NH immediately after their ED visits (Table 3) were more frequently aged 65–74 years (p < 0.01), visited the ED mostly for injuries or cardiovascular problems, and were less frequently transferred with an ambulance (p < 0.01).

Discussion

This study revealed a large (+50 %), significant, and sustained increase in the absolute numbers of NH residents visiting the ED over a 6-year period. Moreover, results show that this increase is disproportionate when considering the modest (+2.5 %) secular increase in nursing home beds in the study area during the period of analysis. Overall, results also suggest that while fewer than one in five (18.8 %) NH residents visited the ED in 2005, this proportion grew to more than one in four (27.5 %) in 2010. These results are important from several perspectives. First, the disproportionate number of ED visits by NH residents and its increase over time raise the critical issues of its causes, and, in turn, of the appropriateness of this use [12]. The relatively high percentages (ranging from 34.0 to 41.6 %) of residents directly discharged back to their NH observed over the study period could be interpreted as supporting the hypothesis of an increased inappropriate ED use. In particular, residents discharged back directly to their NH were younger, arrived less frequently with an ambulance, suffered less severe diseases (most frequently injuries), resulting in lower mortality rate (1.4 vs 8.7 % for those hospitalized). These residents might more frequently suffer from ambulatory care sensitive conditions [7, 8]. However, even though some fluctuation was observed in the percentage of NH residents discharged directly back to their NH, there was no progressive and sustained trend over time, and no indication suggesting a lower threshold in deciding to transfer unstable residents to the ED. Therefore, even though some of the ED utilization by NH residents might be inappropriate, it does not explain the disproportionate increased ED visits over time. Alternatively, higher ED use could just reflect the increasingly sicker and disabled NH population, as shown in some previous study [13]. However, none of the clinical (ED and hospital death rate, reasons for transfer to ED) and administrative (mode of admission, hospital admission rate) data evolved in a direction that would lend support to this hypothesis.

The major reasons for ED visits were trauma, respiratory, and cardiovascular problems. They remained the same over the study period. Unexpectedly, fever was considered only in about 6.3 %. This unusually low rate of fever and therefore of potential infectious diseases is probably related to the classification, as some of the respiratory, digestive or urinary problems were in fact infectious problems. Another explanation could be that this evolution reflects the combined effect of changes in NH residents or caregivers’ expectations, NH staff care delivery, as well as possible correction of prior ED underuse. The progressive reduction of primary care physicians and their relative unavailability, payment-related insurance’s rules, and current organization of NH and community health services—centered on the hospital—altogether favor the transfer of the NH residents [14, 15]. Patient’s habits, family wishes and the emerging fear of legal litigations could simultaneously promote ultra-safe behaviors [16]. Future studies would need to investigate these hypotheses to define the most appropriate interventions to address these factors.

An additional original contribution of the current study is to challenge some common beliefs about the NH population visiting the ED. As observed in previous studies, ED visit rates appear higher in NH residents than in community-dwelling elderly persons, raising specific management issues and challenges regarding their care [4, 7]. However, results of the current study also reveal a strikingly similar pattern of ED use among NH residents compared to community-dwelling older persons. Age and gender distributions, mode of transfer to the ED, main reasons for ED transfer, as well as visits distribution over the 24-h, ED and hospital LOS, the days of week, and the months of the year were all very similar to those of older persons visiting from the community [4]. In particular, these results challenge a common belief that ED visits by NH residents might reflect periods of lower NH staff coverage such as during the night, week-ends, or holidays.

Among NH residents visiting the ED, two different profiles emerge, corresponding to different outcomes. A substantial minority (37.6 % according to the proportion discharged directly back to their NH) appear to suffer from low acuity or ambulatory care sensitive conditions (mostly related to traumatic injuries), with limited mortality risk (1.4 %) and low readmission rate [17, 18]. Another 56.2 % of the NH residents admitted in the general wards after the ED visits return to the NH. Altogether, more than 65 % of the NH residents visiting the ED returned to their NH. Many of these patients likely deserve limited in-hospital diagnostic or therapeutic procedures usually not available in the NH setting. These results further highlight the need to design alternative ambulatory care pathways able to provide these procedures to avoid a potentially deleterious ED use [19]. In contrast, other residents who visited the ED presented with severe acute illnesses, most frequently related to cardiac, respiratory or neurological diseases, were transferred with an ambulance, required admission, and, in some cases (8.7 %), died during their stay. These results may be explained by the higher prevalence of comorbidities, frailty and disability in many NH residents [13, 17]. Again, early death in the ED may be judged inappropriate for NH residents. Nevertheless, these deaths may also be related to the occurrence of an acute unexpected illness overwhelming the resources and competences of the NH staff, sometimes even in palliative care situations [20, 21]. The current study does not allow the determination of the proportion of these transfers that could be judged futile.

This study also reveals an intriguing increase in readmission rates after immediate ED discharge over the study period, within 30 days, and particularly within 90 days. Again, this observation may reflect an increased frailty in NH residents, lower threshold in NH staff to transfer residents to the ED, or, alternatively, more frequent decisions from the ED staff to avoid hospital admission in some NH residents in the context of hospital overcrowding [6, 22].

Limitations of this study include the retrospective use of routinely collected data, prone to measurement errors and missing data. In particular, due to frequent non-documentation of outcomes in the administrative database, data related to the outcomes after discharge from hospital were missing in 28 %, precluding any comparison about in-hospital mortality between NH resident and community-dwelling patients. In addition, data were limited on the initial reasons for ED transfer, as well as on tests and interventions performed during and after the ED stay, precluding any judgment about appropriateness of ED visits. Functional and cognitive status on ED arrival and discharge, prevalence of delirium or falls while in the ED, or drug use in the ED were not available through this epidemiological study. Finally, data are reported from a single institution in a specific context. Generalization of results to other healthcare systems should therefore be cautious. Strengths are the large sample included and exhaustive data on ED use, as well as the duration of the study period that allowed to investigate secular trends and to provide detailed information on the dynamic of this evolution.

This study reveals a sustained and significant increase in ED use by NH residents over the period 2005–2010 that far exceeds the actual increase of the number of NH residents in the area. This evolution likely results from the combined effects of changes in residents and caregivers’ expectations, NH staff care delivery, as well as possible correction of prior ED underuse. In terms of resources allocation, adverse events and cost-effectiveness; these visits may therefore appear problematic [23, 24]. Overall, our results highlight the need to both improve ED process of care to these frail patients, as well as to identify and implement interventions to address these increased needs at the NH level and prevent potentially unnecessary ED transfers [8, 17, 19].

Future research studies may specifically address these issues, including cost-effectiveness aspects. Improving primary care services and NH staffing levels with trained registered nurses or nurse practitioners have been suggested to reduce the number of NH resident transfers to the ED [15, 25]. In addition, clinical practice tools and communication strategies, as well as telemedicine, are of key value in reducing the risk of care discontinuity in nursing home to emergency department transitions [26, 27]. Finally, financial models and incentives have been proposed to promote prevention strategies, primary care services and palliative care services [24, 28].

References

Demographic change in the Euro Area (2006) Projections and consequences. In: Bulletin Monthly (ed) European Central Bank (ECB). European Central Bank, Frankfurt am Main, pp 49–64

Roberts DC, McKay MP, Shaffer A (2008) Increasing rates of emergency department visits for elderly patients in the United States, 1993–2003. Ann Emerg Med 51:769–774

Platts-Mills TF, Leacock B, Cabanas JG et al (2010) Emergency medical services use by the elderly: analysis of a statewide database. Prehosp Emerg Med 14:329–333

Vilpert S, Jaccard-Ruedin H, Trueb L et al (2013) Emergency department use by oldest-old patients from 2005 to 2010 in a Swiss University hospital. BMC Health Serv Res 13:344

Wang HE, Shah M, Allman RM et al (2011) Emergency department visits by nursing home residents in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc 59:1864–1872

Graverholt B, Riise T, Jamtverd G et al (2011) Acute hospital admission among nursing home residents: a population-based observational study. BMC Health Serv Res 11:126

Dwyer R, Gabbe B, Stoelwinder JU et al (2014) A systematic review of outcomes following emergency transfer to hospital for residents of aged care facilites. Age Ageing 43:759–766

Brownell J, Wang J, Smith A et al (2014) Trends in Emergency Department visits for ambulatory care sensitive conditions by elderly nursing home residents, 2001–2010. JAMA Internal Med 174:156–157

Rutschmann OT, Geissbuhler A, Moujber M et al (2008) Computerized triage simulation as a tool to compare the reliability and the performance of triage scales. Ann Emerg Med 52:S57

Rutschmann O, Kossovsky M, Geissbühler A et al (2006) Interactive triage simulator revealed important variability in both process and outcome of emergency triage. J Clin Epidemiol 59:615–621

Stata Statistical Software (2013) Release 13 [computer program]. StataCorporation, College Station

Xing J, Mukamel DB, Temkin-Greener H (2013) Hospitalizations among nursing home residents in the last year of life: nursing home characteristics and variation in potentially avoidable hospitalizations. J Am Geriatr Soc. doi:10.1111/jgs.12517

Falconer M, O’Neill D (2007) Profiling disability within nursing homes: a census-based approach. Age Ageing 36:209–213

Frank C, Seguin R, Haber S et al (2006) Medical directors of long-term care facilities. Preventing another physician shortage? Can Fam Physician 52:752–753

Codde J, Arendts G, Frankel J et al (2010) Transfers from residential aged care facilities to the emergency department are reduced through improved primary care services: an intervention study. Australas J Ageing 29:150–154

Lowthian JA, Smith C, Stoelwinder JU et al (2013) Why older patients of lower clinical urgency choose to attend the Emergency Department. Internal Med J 43:59–65

Gruneir A, Bell CM, Bronskill SE et al (2010) Frequency and pattern of Emergency Department visits by long-term care residents—a population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc 58:510–517

Burke RE, Rooks SP, Levy C et al (2015) Identifying potentially preventable emergency department visits by nursing home residents in the Unites States. J Am Med Dir Assoc 16:395–399

Aminzadeh F, Dalziel WB (2002) Older adults in the emergency department: a systematic review of patterns of use, adverse outcomes, and effectiveness of interventions. Ann Emerg Med 39:238–247

Ahear DJ, Jackson TB, McIlmoyle J et al (2010) Improving end of life care for nursing home residents: an analysis of hospital mortality and readmission rates. Postgrad Med J 86:131–135

Carron PN, Dami F, Diawara F et al (2014) Palliative care and prehospital emergency medicine: time for a new paradigm? Medicine 93:e128

Gruneir A, Bronskill S, Bell C et al (2010) Recent health care transitions and Emergency Department use by chronic long term care residents: a population-based cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 13:202–210

Arendts G, Dickson C, Howard K et al (2012) Transfer from residential aged care to emergency departments: an analysis of patient outcomes. Intern Med J 42:75–82

Ouslander JG, Berenson RA (2011) Reducing unnecessary hospitalizations of nursing home residents. N Engl J Med 365:1165–1167

Morphet J, Innes K, Griffiths DL et al (2015) Resident transfers from aged care facilities to emergency departments: can they be avoided? Emerg Med Austral 27:412–418

Katz PR, Resnick B, Ouslander JG (2015) Requiring on-site evaluation in the nursing home before hospital transfer: is this proposed CMS rule change feasible and safe? JAMDA 16:801–803

Arendts G, Reibel T, Codde J, Frankel J (2010) Can transfers from residential aged care facilities to the Emergency Department be avoided through improved primary care services? Data from qualitative interviews. Austral J Ageing 29:61–65

Ouslander JG, Bonner A, Herndon L, Shutes J (2014) The interventions to reduce acute care transfers (INTERACT) quality improvement program: an overview for medical directors and primary care clinicians in long term care. JAMDA 15:162–170

Acknowledgments

Preliminary results of this study were presented as an oral presentation at the Swiss Congress of Internal Medicine (SCIM) in Basel, Switzerland on May 20th 2015.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of human and animal rights

The study was approved by the State Authorities and by the Lausanne University Ethics Committee.

Informed consent

Because of the retrospective nature of this research and its anonymity, the study did not require personal information or explicit agreement of the patients. Patients admitted at the Lausanne University Hospital received systematic information about the use of de-identified anonymous data for the purpose of retrospective studies.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carron, PN., Mabire, C., Yersin, B. et al. Nursing home residents at the Emergency Department: a 6-year retrospective analysis in a Swiss academic hospital. Intern Emerg Med 12, 229–237 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-016-1459-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-016-1459-x