Abstract

Electronic cigarettes (e-Cigarette) are battery-operated devices designed to vaporise nicotine that may aid smokers to quit or reduce their cigarette consumption. Research on e-Cigarettes is urgently needed to ensure that the decisions of regulators, healthcare providers and consumers are evidence based. Here we assessed long-term effectiveness and tolerability of e-Cigarette used in a ‘naturalistic’ setting. This prospective observational study evaluated smoking reduction/abstinence in smokers not intending to quit using an e-Cigarette (‘Categoria’; Arbi Group, Italy). After an intervention phase of 6 months, during which e-Cigarette use was provided on a regular basis, cigarettes per day (cig/day) and exhaled carbon monoxide (eCO) levels were followed up in an observation phase at 18 and 24 months. Efficacy measures included: (a) ≥50 % reduction in the number of cig/day from baseline, defined as self-reported reduction in the number of cig/day (≥50 %) compared to baseline; (b) ≥80 % reduction in the number of cig/day from baseline, defined as self-reported reduction in the number of cig/day (≥80 %) compared to baseline; (c) abstinence from smoking, defined as complete self-reported abstinence from tobacco smoking (together with an eCO concentration of ≤10 ppm). Smoking reduction and abstinence rates were computed, and adverse events reviewed. Of the 40 subjects, 17 were lost to follow-up at 24 months. A >50 % reduction in the number of cig/day at 24 months was shown in 11/40 (27.5 %) participants with a median of 24 cig/day use at baseline decreasing significantly to 4 cig/day (p = 0.003). Smoking abstinence was reported in 5/40 (12.5 %) participants while combined >50 % reduction and smoking abstinence was observed in 16/40 (40 %) participants at 24 months. Five subjects stopped e-Cigarette use (and stayed quit), three relapsed back to tobacco smoking and four upgraded to more performing products by 24 months. Only some mouth irritation, throat irritation, and dry cough were reported. Withdrawal symptoms were uncommon. Long-term e-Cigarette use can substantially decrease cigarette consumption in smokers not willing to quit and is well tolerated. (http://ClinicalTrials.govnumberNCT01195597).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Cigarette smoking is a remarkably addictive behaviour, and when given the options of smoking or completely giving up tobacco, many smokers will persist in smoking. [1]. For those willing to quit, current smoking cessation medications (such as nicotine replacement therapy—NRT, buproprion and varenicline) are known to increase smoking cessation, particularly if combined with counselling programmes [2].

However, they lack high levels of efficacy in real-life settings [3]. This is known to reflect the chronic relapsing nature of tobacco dependence and more effective approaches are needed to reduce the burden of cigarette smoking.

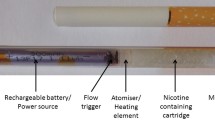

Starting in 2003, electronic cigarettes (e-Cigarettes), battery-operated devices designed to vaporise nicotine without burning tobacco, were introduced in several countries. E-Cigarettes may be attractive to inveterate smokers who consider their tobacco use a recreational habit that they wish to maintain in a more benign form, rather than a problem to be medically treated. Indeed, e-Cigarettes may be considered an alternative low risk substitute for traditional cigarettes [4]. Most e-Cigarettes are designed to look like tobacco cigarettes and may compensate for the visual, sensory, behavioural and social influences on cigarette smoking [4]. Moreover, recent internet surveys [5–7] and preliminary clinical observations with these products [8–10] show that the e-Cigarettes may assist in smoking abstinence, often resulting in an improvement in smoking-related symptoms. Consequently, e-Cigarettes may be an effective and safe cigarette substitute, and therefore merit further evaluation for this purpose.

In spite of these encouraging findings there is concern and debate about the use of e-Cigarettes [4, 11]. This is due to the rapid uptake of this new device in the general population of smokers, lack of regulation and uncertainty of the contents as well as standardisation of cartridges, and the lack of data on long-term safety and tolerability. In view of this, it is important to investigate and establish the efficacy and safety of these devices, particularly after extended use.

We have previously reported that 6-month use of a popular product (‘Categoria’ electronic cigarette; Arbi Group Srl, Italy) can substantially decrease cigarette consumption without causing significant side effects in smokers not intending to quit (10). The aim of the present study was to extend our previous observations and to investigate long-term efficacy and tolerability of the ‘Categoria’ e-Cigarette in the same cohort followed up to 24 months.

Methods

Participants

Adult smokers of ≥15 cigarettes/day (cig/day) for at least 10 years who were not keen to quit smoking at the time of recruitment or in the forthcoming 30 days, were recruited from the local hospital staff in Catania, Italy. Subjects with a documented history of alcohol and illicit drug use, major depression or other psychiatric conditions were excluded from participation. Also, subjects with a recent myocardial infarction, or a history of angina pectoris, high blood pressure (BP > 140 mmHg systolic or 90 mmHg diastolic), diabetes mellitus, severe allergies, poorly controlled asthma or other airways diseases were not recruited. A total of 40 [M 26; F 14; mean (±SD) age of 43.0 (±8.8) years] regular smokers were included in the study (Table 1).

The study protocol was approved by the local institutional ERB (Comitato Etico Azienda Vittorio Emanuele) in February 2010. In consideration of the fact that e-Cigarette use is a widespread phenomenon in Italy, that many e-Cigarette users are enjoying them as consumer goods, that this type of product is not regulated as a drug or a drug device in Italy (end users can buy e-Cigarette almost anywhere—internet, tobacconists, pharmacies, restaurants, and shops), and that only healthy smokers not willing to quit smoking would participate, it was felt that the study fulfilled the criteria of an observational naturalistic investigation and was exempt from the requirement for ethical approval. Participants gave written informed consent prior to participation in the study.

Study design

This was an observational prospective study following a cohort of smokers in a naturalistic setting after a 24-week intervention phase during which participants were issued with Categoria e-Cigarettes. Specifically, eligible participants were invited to use a ‘Categoria’ e-Cigarette (Arbi Group Srl, Italy) for a period of 6 months and followed up prospectively for 2 years. After an initial 6-month intervention phase using the e-Cigarette, participants attended two follow-up visits, at 18 and 24 months, at our smoking cessation clinic (Centro per la Prevenzione e Cura del Tabagismo—CPCT, Università di Catania, Italy) (Fig. 1).

Number of subjects recruited and flow of patients within the study. A total of 66 subjects with specifically predefined smoking criteria (smoking ≥ 15 cig/day for at least the past 10 years) responded to the advertisement; of these, 14 subjects were not included in the study because they spontaneously sought assistance with quitting (these were then invited to attend the local smoking cessation clinic, which offers standard support with cessation counselling and pharmacotherapy for nicotine dependence). The remaining 52 subjects consented to participate into the study; of these, 12 were not considered eligible because of the exclusion criteria (6 had a high blood pressure, 2 were older than 60; 2 had a diagnosis of major depression; 1 suffered from recent myocardial infarction; 1 had uncontrolled allergic asthma). In the end, 40 subjects were included in the study and were issued with e-Cigarette kits loaded with nicotine cartridges. By the end of the study, a total of 17 subjects were lost to follow-up due to failure of attending their control visits. Overall 23 subjects were available for analyses at the 24-month follow-up visit

At baseline, socio-demographic data and a detailed smoking history were annotated together with the ratings of depression and nicotine dependence assessed by Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [12] and by Fagerstrom Test of Nicotine Dependence (FTND) questionnaire [13], respectively. In addition, levels of carbon monoxide in exhaled breath (eCO) were measured using a handheld device (Micro CO, Micro Medical Ltd, UK).

Subjects were then given a free e-Cigarette kit containing two rechargeable batteries, a charger, and two atomizers and instructed on how to charge, activate and correctly use the product. Essential troubleshooting issues were dealt with, and emergency contacts provided for medical and technical support. Free supplies of 7.4 mg nicotine cartridges were provided for the entire duration of the intervention phase. Thorough toxicology and nicotine content analyses of “Original” cartridges had been conducted previously in a laboratory certified by the Italian Institute of Health (http://www.liafonlus.org/public/allegati/categoria1b.pdf).

Participants were permitted a daily usage of the study product ad libitum (but up to a maximum of 4 cartridges/day, as recommended by the manufacturer).

Subjects were informed that the product was a healthier alternative to tobacco smoke, and could be freely used as a tobacco cigarette substitute, as much as they liked. No other specific instructions were given. Participants were requested to fill a 2-week’ study diary recording product use, number of any tobacco cigarettes smoked, and adverse events.

Participants attended three further visits at week-4, week-8, and week-12, during which they received further free supplies of nicotine cartridges together with the study diaries for the residual study periods. The same assessments as for baseline (collection of dairy cards, unused cartridges and eCO measurements) were carried out.

At week-24, by the end of the intervention phase of the study, no more cartridges were provided by the investigators, but participants were advised to continue using their e-Cigarettes if they wished to do so. Again the same assessments as for the previous visits (collection of dairy cards, unused cartridges and eCO measurements) were repeated.

Thereafter, study participants were contacted to return twice to our clinic for an extended observation period at 18 and 24 months. This follow-up was intended to review smoking habits, cig/day, eCO measurements, adverse events and e-Cigarette use. There were neither incentives nor encouragement for smoking cessation throughout the whole duration of the study, which was primarily intended to capture data on smokers unwilling to quit after using e-Cigarettes in a ‘naturalistic’ setting. Of note, in the observation period there was no restriction to which particular e-Cigarettes’ brand participants wished to use.

Study outcome measures

Efficacy measures used in this study were: (a) ≥50 % reduction in the number of cig/day from baseline, defined as self-reported reduction in the number of cig/day (≥50 %) compared to baseline (together with an eCO level reduction, to objectively document a reduction from baseline), was calculated at each study visit (“reducers”); (b) ≥80 % reduction in the number of cig/day from baseline, defined as self-reported reduction in the number of cig/day (≥80 %) compared to baseline (together with an eCO level reduction, to objectively document a reduction from baseline), was calculated at each study visit (“heavy reducers”); (c) abstinence from smoking, defined as complete self-reported abstinence from tobacco smoking (together with an eCO concentration of ≤10 ppm), was calculated at each study visit (“quitters”). Failing to meet the above criteria defines smoking reduction/cessation failure.

Adverse events, symptoms thought to be related to tobacco smoking and e-Cigarette use and to withdrawal from nicotine were annotated at baseline and at each subsequent study visit.

Statistical analyses

This was an exploratory study with opportunistic sampling and sample size calculations were not performed. Primary and secondary efficacy measures were computed by including all the enrolled subjects, i.e. intention-to-treat analysis—assuming that all those lost to follow-up being classified as failures. The changes from baseline in number of cig/day and in eCO levels were compared with data recorded at subsequent follow-up visits using Mann–Whitney U test as these data were non-parametric. Parametric and non-parametric data were expressed as mean (±SD) and median [interquartile range (IQR)], respectively. Statistical methods were 2-tailed, and p values of <0.05 were considered significant. The analyses were carried out using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) for Windows version 17.0.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 40 [M 26; F 14; mean (±SD) age of 43.0 (±8.8) years] regular smokers [mean (±SD) pack/years of 34.9 (±14.7)] were included in the study (Table 1). Twenty-three out of 40 (57.5 %) participants completed all study visits and returned for their final follow-up visit at 24 months (Fig. 1). Baseline characteristics of those who were lost to follow-up were not significantly different from participants who completed the study.

Outcome measures

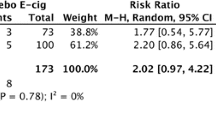

Participants’ smoking status at different stages of the study is illustrated in Table 2. Taking the whole study cohort (n = 40), an overall 80 % reduction in median [IQR] cig/day use from 25 [20, 30] to 4 [3.25, 4] was observed by the end of the study (p < 0.001). Sustained 50 % reduction in the number of cig/day at 24 months was shown in 11/40 (27.5 %) subjects, with a median [IQR] of 24 [19, 27.5] cig/day decreasing significantly to 4 [4, 5] cig/day (p = 0.003). Of these eleven tobacco smoke reducers, six (15 % of the whole study cohort) could be classified as sustained heavy reducers (at least 80 % reduction in the number of cig/day) at 24 months. They had a median [IQR] consumption of 27.5 [24, 32.5] cig/day at baseline, decreasing significantly to 4 [3.25, 4] cig/day by 24 months (p = 0.012). There were 5/40 (12.5 %) quitters by the end of the study. Overall, combined sustained 50 % reduction and smoking abstinence was shown in 16/40 (40 %) participants by 24 months, with a median [IQR] of 24.5 [20, 30] cig/day decreasing significantly to 4 [0, 5] cig/day (p < 0.001). Details of changes in cigarette daily use throughout the study are shown in Fig. 2A. There was a significant reduction in eCO from the whole study cohort (n = 40) of 23.5 [22, 36] to 8 [5, 9.25] at 24 months (p = 0.011). In the 11/40 subjects who had sustained 50 % reduction at the end of the study had a reduction in eCO from 24 [17, 36.5] at baseline to 10 [8.5, 12] at 24 months (p = 0.006). Similarly, there were a marked reduction in the eCO levels from baseline to end of study in the subjects who had >50 % reduction in smoking and quitters together of 27.5 [16.5, 38.75] to 8.5 [5.75, 11.25] (p = 0.001), respectively.

Details of changes in eCO levels throughout the study are shown in Fig. 2B.

Product use

During the intervention phase of the study, the reported number of cartridges/day used by our study participants was variable, ranging from a maximum of 4 cartridges/day (as per the manufacturer’s recommendations) to a minimum of 0 cartridges/day (‘zero’ was recorded in the study diary, when the same cartridge was used for more than 24 h). For the whole group (n = 23), a mean of 1.82 (±1.44) cartridges/day was used at 6 months. The number of cartridges/day used was slightly higher when these summary statistics were computed with the exclusion of study failures; the value increasing to a mean (±SD) of 2.06 (±1.44) cartridges/day.

During the observation phase of the study, it was not possible to accurately establish cartridge usage. The “Categoria” e-Cigarette provided in this study (model “401”) was underperforming compared with current models and it was discontinued from production at some point during the follow-up phase. As a result of this, at 24-month review, some e-Cigarette users (n = 5) were not using the product (and stayed quit), some (n = 3) relapsed back to tobacco smoking and four upgraded their entry level e-Cigarette to better performing intermediate products using e-liquid nicotine from refill bottles (all categorised as heavy reducers).

Tolerability and adverse events

Participants’ most frequently reported adverse events at different stages of the study are detailed in Table 3. At 6 months, mouth irritation, throat irritation, and dry cough were reported, respectively by 14.8, 7.4, and 11.1 % of the participants. Dry mouth, dizziness, headache and nausea were infrequent. Overall, these symptoms remained stable during the whole duration of the observation phase, with the exception of dizziness and nausea, which disappeared by 24-month study visit. Remarkably, side effects commonly recorded during smoking cessation trials with drugs for nicotine addiction (i.e. depression, anxiety, insomnia, irritability, hunger, constipation) were uncommon. Moreover, no serious adverse events (i.e. events requiring unscheduled visit to the family practitioner or hospitalisation) occurred during the intervention and observation phase.

Discussion

Here, we report for the first time important and persistent long-term modifications in the smoking habit of smokers not intending to quit after e-Cigarettes’ use, resulting in significant smoking reduction and smoking abstinence, good tolerability and no apparent increase in withdrawal symptoms. Participants were keen about using the e-Cigarette and many (23/40; 57.5 %) were also able to adhere to the programme and to return for the final follow-up visit at 24 months with an overall quit rate of 12.5 %. Moreover, >50 % reduction in cigarette smoking was observed in 27.5 % of participants, with a substantial reduction from 24 to 4 cig/day. Overall, combined reduction and smoking abstinence was shown in 40 % of participants by the end of the study.

These results are important in view of the fact that all smokers in the study were, by inclusion criteria, not interested in quitting. Moreover, the reported large magnitude of success rates in the present study suggests the e-Cigarette strongly suppressed cigarette use. Hence, these products in the context of such a realistic setting appear to be far more effective than pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation outside of the context of a clinical trial. For example, Balfour et al. [14] estimate that the 12-month quit rate associated with the use of NRT in non-trial settings is approximately 10 %. Apelberg et al. [15] using evidence-based simulation models, estimate that the long-term quit rate associated with NRT use would not exceed 10 %, even if every smoker eventually used NRT with every quit attempt. Last but not least, using data from the 1991 to 2010 National Health Interview Surveys, Zhu et al. [16] show that despite the dramatic increase in the use of pharmacotherapy, there has been no corresponding increase in the population cessation rate over the same period of time. In trying to provide an explanation for the efficacy of these products compared to the existing pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation, it must be considered that, unlike existing pharmaceutical agents, they address simultaneously the behavioural and pharmacological aspects of smoking addiction. As a matter of fact, in consideration of the marked suppression of smoking, it was surprising to note such low nicotine cartridge consumption (i.e. an average of two cartridges/day) during the intervention phase of the study. This indicates that the positive effect of the e-Cigarette may be also due to its capacity to provide a coping mechanism for conditioned smoking cues by replacing some of the rituals associated with smoking gestures. In agreement with this, we have recently demonstrated that even nicotine-free inhalators can improve quit rates in those smokers for whom handling and manipulation of the cigarette play an important role in their ritual of smoking [17].

During the observation phase of the study, it was not possible to accurately establish cartridge usage because the model under investigation was discontinued from production. As a result of this, some regular e-Cigarette users (n = 5) were not using the product anymore at 24-month review (and totally abstaining from smoking), three relapsed back to tobacco smoking and four upgraded their entry level e-Cigarette to better performing intermediate products (i.e. tank system products using e-liquid nicotine from refill bottles). These perhaps are key informative findings of the present study. In clear disagreement with some unsubstantiated concerns suggesting that e-Cigarettes may sustain nicotine addiction, this study provides evidence that 5 out of 23 smokers not intending to quit were able to bring to an end their nicotine addiction. It is possible that the reduction in cigarette smoking caused by e-Cigarette use may well increase motivation to quit as indicated by a substantial body of evidence showing that gradually cutting down smoking can increase subsequent smoking cessation among smokers [18–22]. While not the treatment of choice, reduced smoking strategies might be considered for recalcitrant smokers unwilling to quit, as in the case of our study population. There were, however, three participants who relapsed back to tobacco cigarette consumption because the e-Cigarette under investigation was unavailable or underperforming. Of note, four participants liked the idea of switching to e-Cigarette so much that they decided to upgrade to more rewarding intermediate products.

Given that the model under investigation is not very efficient at delivering nicotine [23], this could have been also a likely reason for some e-Cigarette users to advance to newer more efficient cartonized and tank models.

Taken together, these findings suggest that the risk of relapsing back to tobacco smoking can be prevented by introducing to consumers a larger selection of high quality products. In addition, to being realistic alternatives, e-Cigarettes need to be as readily available as cigarettes, socially acceptable and approved for regular long-term recreational use [24].

According to the opinion of some tobacco control experts, these products might lead to initiation of new smokers or stop cessation efforts for smokers who used it with regular cigarettes.

However, there is no evidence to support these concerns, and findings of the present paper clearly show the opposite, i.e. that e-Cigarettes appear to be a gateway to stopping tobacco use. Surveys and focus groups conducted in South Korea, the US and Poland [25–28] indicate many young people are aware of e-Cigarettes, and a small proportion, some of whom are not tobacco smokers, are willing to try, or have tried them. But, these studies do not indicate that e-Cigarettes are a gateway product to tobacco use.

Long-term e-Cigarette use not only decreases cigarette consumption in smokers not willing to quit, but is well tolerated. This is in agreement with the recent surveillance of e-Cigarette’s adverse event reports by the Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [29]. In this 24-month prospective observational study, mouth irritation, throat irritation, and dry cough were most common and reported in 7.4–14.8 % of the participants. These are likely to be secondary to exposure to propylene glycol (PG) or vegetable glycerine (VG) mist generated by the e-Cigarette’s atomizer.

PG and VG are alcoholic compounds that have been extensively studied for many years, and have been classified as GRAS (Generally Regarded As Safe) by the FDA. They are used as humectants, solvents, and preservatives in food, and for tobacco products as well as being largely used in pharmaceutical (including liquid formulations for nebulization) and personal care products [30, 31].

In humans, there is evidence that short-term exposure to concentrated PG mist (309 mg/m3) may cause, in susceptible individuals, eye and respiratory irritation, cough and slight airway obstruction [32]. Exposure to PG mist is also known to occur from smoke generators in discotheques, theatres, and aviation emergency training settings [33]. At the concentration used in the electronic cigarette liquid PG is not-toxic [34], but more work is required to elucidate any long-term health effects of e-Cigarettes’ vapour and to the presence of vapour contaminants (e.g. pyrolisis byproducts of PG and VG that can be generated under critical conditions of use).

Typical withdrawal symptoms reported during smoking cessation trials with drugs for nicotine addiction (i.e. depression, anxiety, insomnia, irritability, hunger, constipation) were uncommon. It is possible that the e-Cigarette by providing a coping mechanism for conditioned smoking cues could mitigate withdrawal symptoms associated with smoking reduction and nicotine abstinence.

Moreover, no serious adverse events or symptoms from nicotine overdose were reported. Last but not least, smoking reduction with ‘Categoria’ e-Cigarette use was associated with a substantial decrease in levels of carbon monoxide. This is in agreement with previous studies with other brands/models [35, 36].

There are some limitations in our study. First, this was a small uncontrolled study, hence the results observed must be interpreted with caution. However, the observed intent-to-treat success rate of 12.5 % at 2-year follow-up compares favourably with the reported official annualised average cessation rate in the Italian general smoking population of 0.02 %. We are confident that these findings cannot simply relate to participants self-selection (www.istat.it).

Second, 42.5 % of the participants failed to attend their final follow-up visit, but this is not unexpected in an extended smoking cessation/reduction study. Third, because of its unusual design (smokers not willing to quit, e-Cigarettes were used throughout the entire duration of the intervention period) this is not an ordinary cessation study and therefore, direct comparison with other smoking cessation products cannot be made. Fourth, failure to complete the study and smoking cessation/reduction failures could have been the consequence of the frequency of technical issues (e.g. e-Cigarette malfunctions). Fifth, at time of writing the product investigated (model “401”) has become obsolete and is now discontinued from production; findings with the product tested cannot be extended to other models and in particular to newer higher quality products. Sixth, because assessment of withdrawal symptoms in our study was not rigorous and subject to recall bias, the reported lack of withdrawal symptoms in the study participants must be viewed with caution. Last but not least, the effectiveness and tolerability findings reported from healthy smokers recruited from the local hospital staff may not be valid for smokers with other co-morbidities. However, current e-Cigarette research programme at the University of Catania has expanded to include special populations and positive results with the same e-Cigarette model that has also been recently reported in smokers with schizophrenia [37].

In spite of these limitations, the data presented here may still prove helpful to researchers, policy makers, regulators, healthcare providers and consumers in a context where virtually no information about long-term effectiveness and tolerability of e-Cigarettes is available.

In conclusion, persistent long-term modifications in the smoking habit of smokers not intending to quit can be attained by using e-Cigarettes. This behaviour could be sustained over a prolonged period of time by advancing to newer more efficient models, which were well tolerated by users. Although not formally regulated, the e-Cigarette can help smokers unable or unwilling to quit to remain abstinent or reduce their cigarette consumption [38, 39] and currently may represent the ultimate tobacco cigarettes substitute.

Abbreviations

- e-Cigarette:

-

Electronic Cigarette

- ENDD:

-

Electronic nicotine delivery device

- Cig/day:

-

Cigarettes smoked per day

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- mmHg:

-

Millimetres of mercury

- FTND:

-

Fagerstrom test of nicotine dependence

- BDI:

-

Beck’s depression inventory

- eCO:

-

Exhaled carbon monoxide

- ppb:

-

Parts per billion

- mg:

-

Milligrams

- Cartridges/day:

-

Cartridges used per day

- ppm:

-

Parts per million

- Pack/yrs:

-

Pack-years

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

References

Tobacco Advisory Group of the Royal College of Physicians (2007) Harm reduction in nicotine ddiction: Helping people who can’t quit. Royal College of Physicians, London

Polosa R, Benowitz NL (2011) Treatment of nicotine addiction: present therapeutic options and pipeline developments. Trends Pharmacol Sci 32(5):281–289

Casella G, Caponnetto P, Polosa R (2010) Therapeutic advances in the treatment of nicotine addiction: present and Future. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 1(3):95–106

Caponnetto P, Campagna D, Papale G, Russo C, Polosa R (2012) The emerging phenomenon of electronic cigarettes. Expert Rev Respir Med 6(1):63–74

Etter JF (2010) Electronic cigarettes: a survey of users. BMC Public Health 10:231

Etter JF, Bullen C (2011) Electronic cigarette: users profile, utilization, satisfaction and perceived efficacy. Addiction 106(11):2017–2028

Siegel MB, Tanwar KL, Wood KS (2011) Electronic cigarettes as a smoking-cessation: tool results from an online survey. Am J Prev Med 40(4):472–475

Caponnetto P, Polosa R, Auditore R, Russo C, Campagna D (2011) Smoking cessation with E-cigarettes in smokers with a documented history of depression and recurrign relapses. Int J Clin Med 2:281–284

Caponnetto P, Polosa R, Russo C, Leotta C, Campagna D (2011) Successful smoking cessation with electronic cigarettes in smokers with a documented history of recurring relapses: a case series. J Med Case Rep 5(1):585

Polosa R, Caponnetto P, Morjaria JB, Papale G, Campagna D, Russo C (2011) Effect of an electronic nicotine delivery device (e-Cigarette) on smoking reduction and cessation: a prospective 6-month pilot study. BMC Public Health 11:786

Noel JK, Rees VW, Connolly GN (2011) Electronic cigarettes: a new ‘tobacco’ industry? Tob Control 20(1):81

Beck A, Ward C, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J (1987) Manual for the beck depression inventory. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York

Fagerstrom KO, Schneider NG (1989) Measuring nicotine dependence: a review of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. J Behav Med 12(2):159–182

Balfour D, Benowitz N, Fagerstrom K, Kunze M, Keil U (2000) Diagnosis and treatment of nicotine dependence with emphasis on nicotine replacement therapy. A status report. Eur Heart J 21(6):438–445

Apelberg BJ, Onicescu G, Avila-Tang E, Samet JM (2010) Estimating the risks and benefits of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation in the United States. Am J Public Health 100(2):341–348

Zhu SH, Lee M, Zhuang YL, Gamst A, Wolfson T (2012) Interventions to increase smoking cessation at the population level: how much progress has been made in the last two decades? Tob Control 21(2):110–118

Caponnetto P, Cibella F, Mancuso S, Campagna D, Arcidiacono G, Polosa R (2011) Effect of a nicotine-free inhalator as part of a smoking-cessation programme. Eur Respir J 38(5):1005–1011

Bolliger CT, Zellweger JP, Danielsson T, van Biljon X, Robidou A, Westin A, Perruchoud AP, Sawe U (2000) Smoking reduction with oral nicotine inhalers: double blind, randomised clinical trial of efficacy and safety. BMJ 321(7257):329–333

Hughes JR, Carpenter MJ (2005) The feasibility of smoking reduction: an update. Addiction 100(8):1074–1089

Rennard SI, Glover ED, Leischow S, Daughton DM, Glover PN, Muramoto M, Franzon M, Danielsson T, Landfeldt B, Westin A (2006) Efficacy of the nicotine inhaler in smoking reduction: a double-blind, randomized trial. Nicotine Tob Res 8(4):555–564

Walker N, Bullen C, McRobbie H (2009) Reduced-nicotine content cigarettes: is there potential to aid smoking cessation? Nicotine Tob Res 11(11):1274–1279

Wennike P, Danielsson T, Landfeldt B, Westin A, Tonnesen P (2003) Smoking reduction promotes smoking cessation: results from a double blind, randomized, placebocontrolled trial of nicotine gum with 2-year follow-up. Addiction 98(10):1395–1402

Goniewicz ML, Kuma T, Gawron M, Knysak J, Kosmider L (2012). Nicotine Levels in Electronic Cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res

Britton J (2003) Smokeless tobacco: friend or foe? Addiction 98(9):1199–1201 Discussion 1204–1197

Cho JH, Shin E, Moon SS (2011) Electronic-cigarette smoking experience among adolescents. J Adolesc Health 49:542–546

Choi K, Fabian L, Mottey N, Corbett A, Forster J (2012) Young adults’ favorable perceptions of snus, dissolvable tobacco products, and electronic cigarettes: findings from a focus group study. Am J Public Health 102(11):2088–2093

Pepper JK, Reiter PL, McRee AL, Cameron LD, Gilkey MB, Brewer NT (2013) Adolescent males’ awareness of and willingness to try electronic cigarettes. J Adolesc Health 52(2):144–150

Goniewicz ML, Zielinska-Danch W (2012) Electronic cigarette use among teenagers and young adults in Poland. Pediatrics 130(4):e879–e885

Chen I-L (2013) FDA summary of adverse events on electronic cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res 15(2):615–616

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (1973) Select committee on GRAS substances (SCOGS) Opinion: propylene glycol, SCOGS report number 27

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (1975) Select committee on GRAS substances (SCOGS) opinion: glycerin and glycerides, SCOGS report number 30

Wieslander G, Norback D, Lindgren T (2001) Experimental exposure to propylene glycol mist in aviation emergency training: acute ocular and respiratory effects. Occup Environ Med 58(10):649–655

Varughese S, Teschke K, Brauer M, Chow Y, van Netten C, Kennedy SM (2005) Effects of theatrical smokes and fogs on respiratory health in the entertainment industry. Am J Ind Med 47(5):411–418

Werley MS, McDonald P, Lilly P et al (2011) Non-clinical safety and pharmacokinetic evaluations of propylene glycol aerosol in Sprague-Dawley rats and Beagle dogs. Toxicology 287(1–3):76–90

Vansickel AR, Cobb CO, Weaver MF, Eissenberg TE (2010) A clinical laboratory model for evaluating the acute effects of electronic “cigarettes”: nicotine delivery profile and cardiovascular and subjective effects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 19(8):1945–1953

Bullen C, McRobbie H, Thornley S, Glover M, Lin R, Laugesen M (2010) Effect of an electronic nicotine delivery device (e cigarette) on desire to smoke and withdrawal, user preferences and nicotine delivery: randomised cross-over trial. Tob Control 19(2):98–103

Caponnetto P, Auditore R, Russo C, Cappello GC, Polosa R (2013) Impact of an electronic cigarette on smoking reduction and cessation in schizophrenic smokers: a prospective 12-month pilot study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 10(2):446–461

Caponnetto P, Campagna D, Cibella F, Morjaria JB, Caruso M, Russo C, Polosa R (2013) Efficiency and safety of an electronic cigarette (ECLAT) as tobacco cigarettes substitute: A prospective 12-month randomized control design study. Plos One (in press)

Caponnetto P, Keller E, Bruno CM, Polosa R (2013) Handling relapse in smoking cessation: strategies and recommendations. Intern Emerg Med 8:7–12

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Arbi Group Srl (Milano, Italy) for the free supplies of ‘Categoria’ e-Cigarette kits and nicotine cartridges as well as their support. We would also like to thank the study participants for all their time and effort and LIAF (Lega Italiana AntiFumo) for the collaboration.

Conflict of interest

JBM has received lecture fees from Pfizer. RP has received lecture fees from Pfizer and, from Feb 2011, he has been serving as a consultant for Arbi Group Srl.Arbi Group Srl (Milano, Italy), the manufacturer of the e-Cigarette supplied the product, and unrestricted technical and customer support. They were not involved in the study design, running of the study or analysis and presentation of the data. None of the authors have any competing interests to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Polosa, R., Morjaria, J.B., Caponnetto, P. et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of electronic cigarette in real-life: a 24-month prospective observational study. Intern Emerg Med 9, 537–546 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-013-0977-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-013-0977-z