Abstract

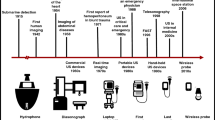

Ultrasonography (US) is an invaluable tool in the management of many types of patients in Internal Medicine and Emergency Departments, as it provides rapid, detailed information regarding abdominal organs and the cardiovascular system, and facilitates the assessment and safe drainage of pleural or intra-abdominal fluid and placement of central venous catheters. Bedside US is a common practice in Emergency Departments, Internal Medicine Departments and Intensive Care Units. US performed by clinicians is an excellent risk reducing tool, shortening the time to definitive therapy, and decreasing the rate of complications from blind invasive procedures. US can be performed at different levels of practice in Internal Medicine, according to the experience of ultrasound practitioners and equipment availability. In this review, the indications for bedside US that can be performed with basic or intermediate US training will be highlighted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ultrasonography (US) has become an invaluable tool in the management of many types of patients. Its safety and portability allows its use at the bedside to provide rapid, detailed information regarding abdominal organs and the cardiovascular system. In addition, bedside US facilitates the assessment and safe drainage of pleural or intra-abdominal fluid and placement of central venous catheters.

It is clearly recognized that ultrasound technologies are not exclusive to radiologists or cardiologists, but can be performed and interpreted by other clinicians. The utility and safety of bedside US performed by clinicians has been fully demonstrated in Emergency Departments (ED) and Intensive Care Units (ICU) [1–4]. In the ED, US allows rapid diagnostic assessment of the patient, and supports the physician in the decision-making process; in ICU, bedside US can provide detailed information about the cardiovascular system and many internal organs without the potential risks connected to patient transport out of the ICU to the radiology suite. Internal Medicine Departments are another setting in which clinician-performed US is widespread for the management of both in-hospital and outpatients, especially in Asiatic and European countries (including Italy). Even if no extensive literature supports the use of US in Internal Medicine Departments, patients in these Departments may be affected by virtually all the conditions in which US has been validated in ED settings (abdominal pain, acute urinary retention, the need to perform invasive procedures). In Italy, US is widely used in Internal Medicine Departments, and in some regions (including Emilia Romagna), the use of this method is included in the minimum requirements for regional accreditation.

US can be performed at different levels of practice in Internal Medicine, according to the experience of ultrasound practitioners and equipment availability. The European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (EFSUMB) defines three levels of practice: [5] level 1 is characterized by ability in performing common examinations safely and accurately, recognizing the normal anatomy and differentiating it from pathological anatomy; level 2 requires the ability to recognize and correctly diagnose almost all pathology within the relevant organ systems and to perform basic, non-complex ultrasound-guided invasive procedures; level 3 is an advanced level of practice, that implies tertiary referrals from level 1 and 2 practitioners, performing specialized ultrasound examinations, advanced ultrasound-guided invasive procedures, teaching and research activity.

This review will deal mainly with the use of bedside US, which can be carried out in any Internal Medicine or ED by clinicians with basic-intermediate experience of US (levels 1–2 according to EFSUMB).

Bedside US in internal and emergency medicine

Typically, bedside or point-of-care US is a goal-directed, focused US examination that answers brief and important clinical questions regarding a definite symptom or sign [1, 6]. It is an excellent risk reducing tool in increasing diagnostic certainty, shortening the time to definitive therapy, and decreasing complications from blind procedures that carry an inherent risk of complications [7]. Bedside emergency US is complementary to the physical examination, but should be considered as a separate entity that adds anatomic, functional, and physiologic information to the care of the patient. It may be performed as a single examination, or may be repeated due to clinical deterioration or for monitoring pathologic changes.

It is performed, interpreted, and integrated by physicians in an immediate and rapid manner dictated by the clinical scenario. It can be applied to any emergency medical condition in any setting with the limitations of time, patient condition, and operator ability. The most frequent clinical situations that are indications for US are thoraco-abdominal trauma, abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), biliary disease, renal tract disease, suspected ectopic pregnancy, pericardial effusion, evaluation of cardiac activity, and procedures that would benefit from US guidance.

Abdominal US

Bedside US is a useful tool in the overall evaluation of a patient with acute abdominal pain. Other imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT scan) may provide more detailed anatomic information than US, but US has the advantages of being non-invasive, rapidly deployed and does not require removal of the patient from the emergency area. Further, US avoids the delays, costs, specialized technical personnel, the administration of contrast agents and the biohazardous potential of radiation.

Aorta

US allows the rapid evaluation of the abdominal aorta from the diaphragmatic hiatus to the aortic bifurcation. Detection of AAA (Fig. 1) is the primary indication for emergency US imaging of the aorta, though aortic dissection may rarely be detected. Bedside US demonstrates excellent accuracy when used by clinicians to evaluate patients with suspected AAA: many studies show a sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values of over 90% for AAA detection [8, 9]. Patients in whom an AAA is identified, should be assessed for free intraperitoneal fluid using the approach of the focused assessment by sonography in trauma (FAST) [10]. Nevertheless, the absence of free intraperitoneal fluid does not rule out an acute AAA as most acute AAAs presenting to the ED do not have free peritoneal fluid. The presence of retroperitoneal hemorrhage cannot be reliably identified by US.

In a stable patient with abdominal pain and an US diagnosis of AAA, a contrast-enhanced CT scan can be performed to investigate the presence of leakage. However, a hypotensive patient with sonographic evidence of an AAA should be considered to be having an acute rupture, and a vascular surgeon should be consulted to evaluate the immediate transport to the operating room without other time consuming imaging studies.

Biliary system

Right upper quadrant US is the first line imaging technique in patients with signs and symptoms of biliary disease, common in the ED. It is the method of choice for detection of gallstones (Fig. 2), as its sensitivity is higher than that of the CT scan. The test characteristics for gallstone detection by bedside US are: sensitivity 90–96%, specificity 88–96%, positive predictive value 88–99% and negative predictive value 73–96% [1, 11, 12]. Presence of gallstones alone is not sufficient for a diagnosis of acute cholecystitis, but good positive predictive values can be achieved if secondary US findings such as a positive Murphy sign (focal tenderness during compression with the transducer over the gallbladder) or thickened gallbladder wall (>3 mm) are detected in conjunction with gallstones (positive predictive value, respectively, 92 and 95%) [13]. Nevertheless, the US Murphy sign is absent in many cases of gangrenous cholecystitis, and wall thickening may be an expression of other pathologies such as right heart failure or portal hypertension. The CT scan is not routinely needed if the US imaging is diagnostic: but should be used in complicated cases [14].

Jaundice and elevated liver function tests are other common indications for US. It is highly accurate (93%) for demonstration of ductal dilatation, but is less reliable with regard to the cause of obstruction [15], especially in emergency settings. The CT scan demonstrates the location and cause of obstruction more accurately than US.

In particular, US has limited sensitivity for the diagnosis of choledocholithiasis. If choledocholithiasis is suspected, the patients should be referred for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography or magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography.

Urinary tract

The primary indications for this application of US are in the evaluation of obstructive uropathy and acute urinary retention in a patient with clinical findings suggestive of these diseases. Hydronephrosis is the main sonographic abnormality that should be identified in patients with suspected acute renal obstruction. The pitfall of US is that the ureter is often only partially visualized, and stones in the middle tract are rarely displayed. On the contrary, CT scan can routinely identify ureteral stones, and provide accurate measurements of the stone’s size.

When acute renal colic is suspected, bedside US has a sensitivity of 75–87% and specificity of 82–89% when compared with a CT scan [16].

The bladder should be imaged as part of an US study of the kidney and urinary tract, as many indications for this examination are caused by conditions identifiable in the bladder. Moreover, US can provide a measurement of urine volume in the bladder, avoiding bladder overdistension or unnecessary catheterization [17].

Other indications includes hematuria, acute renal failure, suspected abscesses of the kidneys, and gross prostate abnormalities.

Pelvis

First trimester pregnancy complications such as abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding are common complaints in the ED. Studies in this setting show a sensitivity of 76–90% and a specificity of 88–92% for the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy [18, 19].

The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) lists pelvic US as useful tool for emergency physicians to evaluate the presence of intrauterine pregnancy [1]. A complete US study should include the examination of the uterus in at least two planes, the short and long axis, to avoid missing findings. The most common indicator of an intrauterine pregnancy used in emergency medicine is the visualization of a true gestational sac, which appear anechoic and surrounded by hyperechoic chorionic ring. If no intrauterine pregnancy is visualized, an ectopic pregnancy should be considered until proved otherwise: a formal US study and a gynecology consultation are therefore warranted. The pelvis should also be examined for the presence free fluid. A large amount of free fluid is abnormal, and strongly suggests a ruptured ectopic pregnancy in the right clinical setting. For those patients with a concerning history and indeterminate US finding, a gynecologist should be consulted before final disposition [20].

Other possible indications for an US study are evaluation of ovarian cysts and tubo-ovarian abscess.

Bowel

An US study is successfully used in diagnosing acute appendicitis in both children and adults. The sensitivity and specificity of US for acute appendicitis ranges from 80 to 94% and 89 to 100%, respectively [21]. Sonographic signs of acute appendicitis include a non-compressible tubular structure with a diameter of >6 mm at the base of the cecum (Fig. 3). Other signs are luminal distension, concentric thickening of the inflamed appendiceal wall with pain on pressure, and free fluid. Complications of acute appendicitis (perforation and abscess formation with or without generalized peritonitis) can also be detected by an US study.

Many studies, including a meta-analysis, have demonstrated the superiority of the CT scan over an US study in appendicitis. Although the specificity is similar between CT and US (94 and 93%, respectively), the sensitivity is better for the CT scan (94 vs. 83%), and therefore, the overall accuracy is superior as well, ranging from 92 to 97% [22]. False-negative results are possible in patients with a ruptured appendix, and an inconclusive US evaluation is common in obese patients and in those with abnormal amounts of bowel gas. Consequently, a negative or inconclusive US study is not sufficient to exclude acute appendicitis, and a CT study should be arranged. A reduced clinical diagnostic accuracy and a higher rate of ruptured appendix upon presentation can occur in very young patients and the elderly, who therefore are more likely to benefit from a CT scan.

On the contrary, the specificity of a positive US is comparable to that of a CT scan. In patients with a high probability of appendicitis based on both clinical assessment and an US study, a routine CT scan offers no clear advantage, [23] and, in some cases, may lead to unnecessary delay and higher costs. The US study may be best used as an initial study in pediatric patients, women of childbearing age, and pregnant patients when appendicitis is suspected.

An US study is also useful in the initial evaluation of other acute gastrointestinal tract conditions, such as diverticulitis, Crohn’s disease, infectious colitis, bowel malignancy presenting acutely, small bowel obstruction, and intussusception [24].

Trauma

Emergency US evaluation is performed as an integral component of trauma resuscitation [1, 10]. It can be performed with portable equipment, allowing its use in remote or difficult clinical situations, i.e. on patients with spinal immobilization.

FAST examination has been the first validated bedside ultrasound technique studied in the hands of non-radiologists. The aim of FAST is to identify pathologic free fluid released from injured organs, by evaluating the peritoneal, pericardial or pleural spaces in anatomically dependent areas. Four regions or “views” are investigated: the right flank (that allows examination of the pleural space, the subphrenic space, the hepatorenal space and the inferior pole of the kidney), the pericardial view, the left flank (looking for free fluid in the pleural space, the subphrenic space, the splenorenal space, and the inferior pole of the kidney), and the pelvic view (the most dependent peritoneal space in the supine position). Serial US may be performed in response to changes in the patient’s condition, to check for the development of previously undetectable free fluid.

In the literature, many studies have confirmed the utility of FAST, even if its sensitivity for intraperitoneal injury varies widely between studies: a meta-analysis of 62 studies finds an overall pooled sensitivity of 78.9% (66.0% if only highest quality studies are included) and specificity of 99.2% [25]. A prospective randomized controlled trial compared a protocol inclusive of point-of-care US to a protocol without FAST examinations in blunt trauma patients. Patients randomized to the FAST group have more rapid access to the operating room, require fewer CT scans, and incur shorter hospitalizations and fewer complications than those in whom the FAST is not performed [26].

In the patient without evidence of shock or who responds well to fluid resuscitation, FAST is useful as a screening examination for subsequent CT scanning, and as a triage instrument. In this setting, the CT scan is usually considered the appropriate diagnostic modality, as it offers higher sensitivity and specificity. In contrast, in the patient with shock who is not stable enough for a CT scan, a FAST examination should be the primary imaging study, since it scarcely interferes with resuscitation [27].

More recently, an US study has been used in the diagnosis of pneumothorax [28], with sensitivity and specificity >90% combining two or more US signs [29]. In regional trauma, US can be used to detect fractures and musculoskeletal, vascular and testicular injuries.

Lower limb veins

An US study for the diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis evaluates for compressibility of the lower extremity deep venous system [compression ultrasonography (CUS)]. The sonographic evaluation is performed by compressing the vein directly under the transducer while watching for complete apposition of the anterior and posterior walls. The failure to obtain wall apposition is diagnostic for thrombosis. In the simplest approach, compression is applied exclusively to the common femoral vein at the groin and the popliteal vein at the popliteal fossa (2-point or limited CUS). Relevant features of this strategy are simplicity, reproducibility and widespread availability [30]. As calf veins are not evaluated, the repetition of CUS within 1 week is indicated in patients with a negative initial test, but with a high pre-test probability of deep venous thrombosis or a positive d-dimer test. [30, 31] A recent systematic review of CUS performed by emergency physicians shows a pooled sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 96% [32].

An extended approach is characterized by exploration of the whole deep venous system of the leg: the proximal deep veins are examined first, including the common, superficial femoral veins, and the popliteal vein. The calf veins are then also evaluated. The latter approach is thought to be superior based on its ability to detect isolated calf vein thrombosis, but conclusive evidence is not available [33]. This issue is of real importance, as systematically searching for calf deep vein thrombosis potentially doubles the number of patients given anticoagulant treatment without a proven reduction in the 3-month thromboembolic risk. The clinical relevance of distal deep vein thrombosis is still debated, as the few available studies are not conclusive about the embolic potential of isolated calf thrombosis and its rate of extension to proximal deep veins [34]. Moreover, the diagnostic performances of the US study for distal deep vein thrombosis are highly variable according to literature data, but low sensitivity is generally reported (50–75%) [35, 36], except in a few studies performed by highly skilled sonographers using the best available ultrasound equipment. New prospective, well designed outcome studies are needed.

Bedside echocardiography

Simple principles of echocardiography may be very useful to the emergency physician. The primary applications for cardiac emergency US are in the diagnosis of pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade, and in evaluation of gross cardiac function.

A phased array cardiac transducer is optimal, since it facilitates scanning through the narrow intercostal windows, and provides better resolution of rapidly moving cardiac structures. If this is not available, a 2–5 MHz general-purpose curved array probe will suffice. Doppler capability may be helpful in certain extended emergency US indications, but is not routinely used for the primary cardiac US indications. Both portable and cart-based ultrasound machines may be used, depending on the location and setting of the examination.

Test characteristics of echocardiography performed by emergency physicians for the detection of pericardial effusion include sensitivity of 96–100%, specificity 98–100%, positive predictive value 93–100%, and negative predictive value 99–100% when compared to expert over-read of images [1].

The evaluation of gross cardiac motion in the setting of cardiopulmonary resuscitation has a well-established prognostic value. Terminal cardiac dysfunction typically progresses through global ventricular hypokinesis, incomplete systolic valve closure, absence of valve motion, and absence of ventricular motion. The detection of cardiac standstill on US during resuscitation is 100% predictive of mortality, regardless of electrical rhythm [37].

Bedside echocardiography is recently spreading for rapid assessment of cardiac function, thanks to a new generation of portable, inexpensive cardiac US devices. The role of bedside echocardiography in non-cardiologists’ hands is not to replace a complete echocardiogram performed on a standard platform, but to extend information available from just the physical examination. Published investigations demonstrate that emergency physicians and internists with relatively limited training and experience can accurately estimate cardiac ejection fraction [38, 39]. Moreover, in patients with acute heart failure, a chest US study is useful for the noninvasive assessment of extravascular lung water [40].

Other important information obtained through bedside echocardiography include gross estimation of intravascular volume status, and identification of acute right ventricular dysfunction in the setting of suspected pulmonary embolism.

US-guided procedures

Interventional US includes invasive procedures carried out under US guidance for diagnostic and therapeutic aims. Clinicians with limited or intermediate US training may effectively use the US images to guide simple invasive procedures with the advantages of improved patient safety, decreased procedural attempts, and decreased time to perform the procedure [41, 42].

Common procedural uses include drainage of fluid collections that may accumulate in various potential spaces: pericardial effusion (pericardiocentesis), pleural effusion (thoracentesis), peritoneal fluid (paracentesis), and joint effusion (arthrocentesis). An US study can be used to localize the relevant anatomy and pathology before performing the procedure in a sterile manner, or with sterile probe covers and real-time assessment.

US-guided central line placement should be considered in patients in whom cannulation may be difficult. The US imaging can be used to localize and define the anatomy of the vein; subsequently, it can also be used to provide real-time ultrasonographic guidance for insertion of the needle. Multiple studies have reported the superiority of US-assisted cannulation of the internal jugular vein in ICU patients as compared with the external landmark-guided technique. A review of the literature reports that placement of central venous catheters under US guidance significantly decreases placement failure by 64%, decreases complications by 78%, and decreases the need for multiple placement attempts by 40% [43]. Data are less consistent for subclavian venous catheterization.

Conclusion

We believe that first level US studies should be promptly available in Emergency and Internal Medicine Departments, and should, if possible, be carried out directly by the clinician. This approach is characterized by a prompt advantage for the patients, as US decreases diagnostic time, allows rapid definition of an appropriate diagnostic process and quick access to adequate therapy, and consequently shortens hospitalization time.

A large number of practicing emergency physicians are now trained in bedside ultrasound, and this training is currently included in all United States Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Emergency Medicine residency programs. Furthermore, the ACEP has formally endorsed bedside US by the emergency physician for multiple applications.

Similarly, it is advisable for all new Internists to receive adequate training in ultrasonography, in order to allow him/her to perform at least first level US examinations. It is in fact not by chance that the Italian Society of Internal Medicine (SIMI), being aware of young clinician’s training needs, arranges a yearly Summer School in Ultrasonography and Emergency Medicine.

References

American College of Emergency Physicians (2009) Emergency ultrasound guidelines. Ann Emerg Med 53:550–570

Reardon R, Heegaard B, Plummer D, Clinton J, Cook T, Tayal V (2006) Ultrasound is a necessary skill for emergency physicians. Acad Emerg Med 13:334–336

Beaulieu Y, Marik PE (2005) Bedside ultrasonography in the ICU (Part 1). Chest 128:881–895

Beaulieu Y, Marik PE (2005) Bedside ultrasonography in the ICU (Part 2). Chest 128:1766–1781

Valentin L (2006) Minimum training recommendations for the practice of medical ultrasound. Ultraschall Med 27:79–105

Cardenas E (1998) Limited beside ultrasound imaging by emergency medicine physicians. West J Med 168:188–189

Bassler D, Snoey ER, Kim J (2003) Goal-directed abdominal ultrasonography: impact on real-time decision making in the emergency department. J Emerg Med 24:375–378

Kuhn M, Bonnin RL, Davey MJ, Rowland JL, Langlois SL (2000) Emergency department ultrasound scanning for abdominal aortic aneurysm: accessible, accurate, and advantageous. Ann Emerg Med 36:219–223

Tayal VS, Graf CD, Gibbs MA (2003) Prospective study of accuracy and outcome of emergency ultrasound for abdominal aortic aneurysm over two years. Acad Emerg Med 10:867–871

American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (2008) AIUM Practice Guideline for the performance of the focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) examination. J Ultrasound Med 27:313–318

Miller AH, Pepe PE, Brockman CR, Delaney KA (2006) ED ultrasound in hepatobiliary disease. J Emerg Med 30:69–74

Durston W, Carl ML, Guerra W, Eaton A, Ackerson L, Rieland T, Schauer B, Chisum E, Harrison M, Navarro ML (2001) Comparison of quality and cost-effectiveness in the evaluation of symptomatic cholelithiasis with different approaches to ultrasound availability in the ED. Am J Emerg Med 19:260–269

Ralls PW, Colletti PM, Lapin SA, Chandrasoma P, Boswell WD Jr, Ngo C, Radin DR, Halls JM (1985) Real-time sonography in suspected acute cholecystitis: prospective evaluation of primary and secondary signs. Radiology 155:767–771

Harvey RT, Miller WT Jr (1999) Acute biliary disease: initial CT and follow-up US versus initial US and follow-up CT. Radiology 213:831–836

Baron RL, Stanley RJ, Lee JK, Koehler RE, Melson GL, Balfe DM, Weyman PJ (1982) A prospective comparison of the evaluation of biliary obstruction using computed tomography and ultrasonography. Radiology 145:91–98

Gaspari RJ, Horst K (2005) Emergency ultrasound and urinalysis in the evaluation of flank pain. Acad Emerg Med 12:1180–1184

Anton HA, Chambers K, Clifton J, Tasaka J (1998) Clinical utility of a portable ultrasound device in intermittent catheterization. Arch Phys Med Rehab 79:172–175

Durham B, Lane B, Burbridge L, Balasubramaniam S (1997) Pelvic ultrasound performed by emergency physicians for the detection of ectopic pregnancy in complicated first-trimester pregnancies. Ann Emerg Med 29:338–347

Mandavia DP, Aragona J, Chan L, Chan D, Henderson SO (2000) Ultrasound training for emergency physicians. Acad Emerg Med 7:1009–1014

Promes SB, Nobay F (2010) Pitfalls in first-trimester bleeding. Emerg Med Clin North Am 28:219–234

Dietrich CF (2008) Ultrasonography of the small and large intestine. In: UpToDate, Rose BD (eds), UpToDate, Wellesley

Doria AS, Moineddin R, Kellenberger CJ, Epelman M, Beyene J, Schuh S, Babyn PS, Dick PT (2006) US or CT for diagnosis of appendicitis in children and adults? A meta-analysis. Radiology 241:83–94

Poortman P, Oostvogel HJ, Bosma E, Lohle PN, Cuesta MA, de Lange-de Klerk ES, Hamming JF (2009) Improving diagnosis of acute appendicitis: results of a diagnostic pathway with standard use of ultrasonography followed by selective use of CT. J Am Coll Surg 208:434–441

Puylaert JB (2001) Ultrasound of acute GI tract conditions. Eur Radiol 11:1867–1877

Stengel D, Bauwens K, Rademacher G, Mutze S, Ekkernkamp A (2005) Association between compliance with methodological standards of diagnostic research and reported test accuracy: meta-analysis of focused assessment of US for trauma. Radiology 236:102–111

Melniker LA, Leibner E, McKenney MG, Lopez P, Briggs WM, Mancuso CA (2006) Randomized controlled clinical trial of point-of-care, limited ultrasonography for trauma in the emergency department: the first sonography outcomes assessment program trial. Ann Emerg Med 48:227–235

Mackersie RC (2010) Pitfalls in the evaluation and resuscitation of the trauma patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am 28:1–27 Vii

Chan SS (2003) Emergency bedside ultrasound to detect pneumothorax. Acad Emerg Med 10:91–94

Lichtenstein DA, Mezière G, Lascols N, Biderman P, Courret JP, Gepner A, Goldstein I, Tenoudji-Cohen M (2005) Ultrasound diagnosis of occult pneumothorax. Crit Care Med 33:1231–1238

Cogo A, Lensing AW, Koopman MM, Piovella F, Siragusa S, Wells PS, Villalta S, Büller HR, Turpie AG, Prandoni P (1998) Compression ultrasonography for diagnostic management of patients with clinically suspected deep vein thrombosis: prospective cohort study. BMJ 316:17–20

Tick LW, Ton E, van Voorthuizen T, Hovens MM, Leeuwenburgh I, Lobatto S, Stijnen PJ, van der Heul C, Huisman PM, Kramer MH, Huisman MV (2002) Practical diagnostic management of patients with clinically suspected deep vein thrombosis by clinical probability test, compression ultrasonography, and d-dimer test. Am J Med 113:630–635

Burnside PR, Brown MD, Kline JA (2008) Systematic review of emergency physician-performed ultrasonography for lower-extremity deep vein thrombosis. Acad Emerg Med 15:493–498

Bernardi E, Camporese G, Büller HR, Siragusa S, Imberti D, Berchio A, Ghirarduzzi A, Verlato F, Anastasio R, Prati C, Piccioli A, Pesavento R, Bova C, Maltempi P, Zanatta N, Cogo A, Cappelli R, Bucherini E, Cuppini S, Noventa F, Prandoni P (2008) Erasmus Study Group. Serial 2-point ultrasonography plus d-dimer vs whole-leg color-coded Doppler ultrasonography for diagnosing suspected symptomatic deep vein thrombosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 300:1653–1659

Righini M, Bounameaux H (2008) Clinical relevance of distal deep vein thrombosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med 14:408–413

Kearon C, Julian JA, Newman TE, Ginsberg JS (1998) Noninvasive diagnosis of deep venous thrombosis McMaster Diagnostic Imaging Practice Guidelines Initiative. Ann Intern Med 128:663–677

Goodacre S, Sampson F, Thomas S, van Beek E, Sutton A (2005) Systematic review and metaanalysis of the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography for deep vein thrombosis. BMC Med Imaging 5:6

Blaivas M, Fox J (2001) Outcome in cardiac arrest patients found to have cardiac standstill on the bedside emergency department echocardiogram. Acad Emerg Med 8:616–621

DeCara JM, Lang RM, Koch R, Bala R, Penzotti J, Spencer KT (2003) The use of small personal ultrasound devices by internists without formal training in echocardiography. Eur J Echocardiogr 4:141–147

Duvall WL, Croft LB, Goldman ME (2003) Can hand-carried ultrasound devices be extended for use by the noncardiology medical community? Echocardiography 20:471–476

Soldati G, Gargani L, Silva FR (2008) Acute heart failure: new diagnostic perspectives for the emergency physician. Intern Emerg Med 3:37–41

Nazeer SR, Dewbre H, Miller AH (2005) Ultrasound-assisted paracentesis performed by emergency physicians vs the traditional technique: a prospective, randomized study. Amer J Emerg Med 23:363–367

Milling TJ Jr, Rose J, Briggs WM, Birkhahn R, Gaeta TJ, Bove JJ, Melniker LA (2005) Randomized, controlled clinical trial of point-of-care limited ultrasonography assistance of central venous cannulation: The third sonography outcomes assessment program (SOAP-3) trial. Crit Care Med 33:1764–1769

Randolph AG, Cook DJ, Gonzales CA, Pribble CG (1996) Ultrasound guidance for placement of central venous catheters: a metaanalysis of the literature. Crit Care Med 24:2053–2058

Conflict of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arienti, V., Camaggi, V. Clinical applications of bedside ultrasonography in internal and emergency medicine. Intern Emerg Med 6, 195–201 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-010-0424-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-010-0424-3