Abstract

The mission of the European Headache Federation (EHF) is to improve life for those affected by headache disorders in Europe. Progress depends upon improving access to good headache-related health care for people affected by these disorders. Education about headache—its nature, causes, consequences and management—is a key activity of EHF that supports this aim. It is also important to achieve an organisation of headache-related services within the health systems of Europe in order that they can best deliver care in response to what are very high levels of need. This publication assesses this need, and sets out proposals for service organisation, on three levels, to meet the resultant demand.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The mission statement of the European Headache Federation (EHF) sets out its primary purpose: to improve life for those affected by headache disorders in Europe [1]. EHF undertakes a range of activities in pursuit of this aim. “Educating Europe” about headache—its nature, prevalence, causes, consequences and management—is of highest importance. With knowledge of headache, and especially these aspects of it, comes recognition of headache disorders as a major public-health priority, and awareness of the need for effective solutions to them.

While EHF therefore puts much of its efforts into education [2], it does not neglect careful consideration of what these solutions should be, and how they might be implemented. Since better health care for headache and ready access to it are their essence, the organisation of headache-related services within the health systems of Europe becomes an important focus also, in order to maximise both effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. The reality is that levels of need for headache-related health care are very high.

This paper first assesses this need in Europe, and the demand likely to result from it. Then it sets out proposals for service organisation, on three levels, to meet this demand. It is the result of a collaboration between EHF and Lifting The Burden, the World Health Organization’s Global Campaign to Reduce the Burden of Headache Worldwide [3, 4], and of consensus meetings of experts in headache disorders who have particular interest in their public-health implications. In due course, these proposals will be formulated into recommendations to sit alongside other guidance produced by EHF [2, 5].

Headache-related health care needs assessment

According to epidemiological data, among every 1,000,000 people living in Europe there are 110,000 adults with migraine [6, 7], 90,000 of whom are significantly disabled [8]. There are 600,000 people who have occasional other headaches, the majority being episodic tension-type headache and not significantly disabling. And there are 30,000 with chronic daily headache [7], of whom most are disabled and many have medication-overuse headache.

It is reasonable to expect that at least everyone with disabling migraine or chronic daily headache is in need of (that is, likely to benefit from) good headache care. This means 120,000 adults, or 15% of the adult population. Empirical data from a large UK general practice support this: 17% of registered patients aged 16–65 years consulted for headache at least once in 5 years [9]. In addition, needs arise in the child population. There are few data on which to quantify these needs, but they are likely to arise at something like half the rate per head of adults (i.e., 15,000 children per 1,000,000 of the general population). Upon these statistics, with some assumptions, it is possible to make calculations of service requirements.

The numbers that these calculations generate show beyond argument that most headache services must be provided in primary care. This is not a bad thing: most headache diagnosis and management requires no more than a basic knowledge of a relatively few very common disorders, which ought to be wholly familiar to primary-care physicians. Only standard clinical skills, which every physician should have, need to be applied. No special investigations or equipment are usually necessary. Perhaps 10% of presenting patients might appropriately be treated in a specialist headache clinic. The empirical data from the UK general practice again support this: of the adult patients consulting for headache, 9% were referred to secondary care [9].

The first assumption is that “demand” for headache-related health care is expressed by only 50% of those in need (i.e., 50% who might benefit from medical care do not seek it). Further assumptions are that: (1) the minimum consultation need per adult patient in primary care is 1 h in every 2 years, 30 min for the first visit and 30 min in total for 1–3 follow-up appointments; (2) the minimum need per child patient in primary care is double the adult requirement (i.e., 1 h/year); (3) no wastage occurs in primary care through failures by patients to attend appointments; (4) at a specialist level, the minimum consultation need per adult patient in a year is 45 min for the first visit and 15 min in total for follow-up; (5) for children it is higher: say 1.25 h in total; (6) the need for inpatient management is very low (<1% overall of presenting patients) and can be ignored in these calculations; (7) no wastage occurs in specialist care through failures by patients to attend appointments, or it is discounted by overbooking; (8) 1 day per week of each medical full-time equivalent is the minimum requirement for administration, audit and continuing professional development; (9) each week therefore allows 4 days, each of 7 h, of patient-contact time, and 48 weeks are worked per year.

These assumptions are conservative. Despite that, the estimated service requirements expressed in medical full-time equivalents (Table 1) are very challenging. Headache services must be organised, or they cannot possibly be delivered efficiently or equitably.

Organisation of headache services

We suggest the following basis for organisation (Table 2), suitable for most European countries. It sets what are intended as minimum standards to be adapted in accordance with the national health service structure, organisation and delivery.

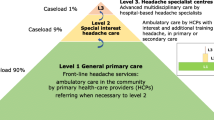

Level 1: Headache primary care should meet the needs of 90% of people consulting for headache, and have referral channels to levels 2 and 3 as needed. Physicians at this level should competently diagnose and manage most migraine and tension-type headache, and recognise other common primary and secondary headache disorders listed as core diagnoses (Table 3). On the assumptions above, one full-time equivalent physician can provide headache care at level 1 for a population no larger than 35,000.

Level 2: Headache clinics should provide care to 10% of patients seen at level 1 who are referred to level 2. They should have a referral channel to level 3 as needed, and access to other services such as neurology, psychology and physiotherapy. Physicians at this level need to offer “special interest” services, in primary care or in secondary care outpatients, and competently diagnose and manage more difficult cases of primary headache and some secondary headache disorders (Table 3). One full-time equivalent physician can provide headache care at level 2 for a population no larger than 200,000.

Level 3: Specialist headache centres should provide advanced care to 10% of patients seen at level 2 who are referred to level 3, and support emergency or acute treatment services for patients presenting with headache. Physicians at this level need to offer specialist headache services in secondary care, with full-time inpatient facilities (minimum 2 beds/million population), and work in a multidisciplinary teams with access to equipment and specialists in other disciplines for diagnosis and management of the underlying causes of all secondary headache disorders. One full-time equivalent physician can provide headache care at level 3 for a population no larger than 2,000,000.

Discussion

The organisation of headache services in Europe has been the subject of few publications [11, 12]. In the UK, the pattern of referrals has been described in detail by Dowson [13, 14]. Most patients who cannot be treated effectively in primary care are referred by their primary-care physicians to neurologists, but some may go to general practitioners with special interest (GPwSIs) in headache [15]. A few end up in specialised secondary-care or academic headache centres. While these options appear to reflect our three proposed levels, there is no formal organisation of services in this way. Much is ad hoc, and many patients do not progress from level 1 who would benefit from doing so. On the other hand, some patients are referred upwards who could, and should, be perfectly well managed by a primary-care physician. A similar approach is not used in other countries such Italy, Spain and France.

It is unfortunately true that the presence of a better, 3-level system in a health-care structure is likely to stimulate demand. But it should be recognised that this is simply unmasking need that is there already. It is crucial, within these proposals, that better knowledge of headache and the use of evidence-based guidelines [5] in primary care keep the great majority of patients at levels 1 and 2, reducing unnecessary demand upon more costly specialist care. This more rational use of health-care resources is the means by which effective care can reach more who need it.

There are, however, major implications for training. These need careful consideration. The start, though it is not easily achieved, is to give more emphasis to headache diagnosis and management in the medical schools undergraduate curriculum. This will ensure at least that newly-qualified doctors will have some understanding of a set of burdensome and very common disorders—which is often not the case now. But there will be much more to do beyond that if headache care, when delivered, is to be optimally effective at all levels. Within the 3-level care system proposed, a training role for each higher level to the level below can be envisaged. It is likely that the entire structure will depend upon these roles being developed.

References

European Headache Federation. EHF missions. EHF at http://www.ehf-org.org/mission.asp. Accessed 5 July 2008

Antonaci F, Láinez JM, Diener H-C et al (2005) Guidelines for the organization of headache education in Europe: the headache school. Funct Neurol 20:89–93

Steiner TJ (2004) Lifting the burden: the global campaign against headache. Lancet Neurol 3:204–205

Steiner TJ (2005) Lifting The Burden: The global campaign to reduce the burden of headache worldwide. J Headache Pain 6:373–377

Steiner TJ, Paemeleire K, Jensen R et al (2007) European principles of management of common headache disorders in primary care. J Headache Pain 8(Suppl 1):S3–S21

Steiner TJ, Scher AI, Stewart WF et al (2003) The prevalence and disability burden of adult migraine in England and their relationships to age, gender and ethnicity. Cephalalgia 23:519–527

Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R et al (2007) Headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia 27:193–210

Lipton RB, Scher AI, Steiner TJ et al (2003) Patterns of health care utilization for migraine in England and in the United States. Neurology 60:441–448

Laughey WF, Holmes WF, MacGregor AE, Sawyer JPC (1999) Headache consultation and referral patterns in one UK general practice. Cephalalgia 19:328–329

Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society (2004) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 2nd edn. Cephalalgia 24(Suppl 1):1–160

Porter ME, Guth C, Dannemiller E (2007) The West German Headache Center: integrated migraine care. Harvard Business Publishing, Boston

Jensen R (2007) Organization of a multidisciplinary headache centre in Europe. In: Jensen R, Diener H-C, Olesen J (eds) Headache clinics: organisation, patients and treatment. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 29–34

Dowson A (2003) Analysis of the patients attending a specialist UK headache clinic over a 3-year period. Headache 43:14–18

Dowson AJ, Bradford S, Lipscombe S et al (2004) Managing chronic headaches in the clinic. Int J Clin Pract 58:1142–1151

Department of Health (2003) Guidelines for the appointment of general practitioners with special interests in the delivery of clinical services: headaches. Department of Health, London

Acknowledgments

Lifting The Burden: the Global Campaign to Reduce the Burden of Headache Worldwide is a partnership in action between the World Health Organization, World Headache Alliance, International Headache Society and European Headache Federation.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest related to the publication of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Antonaci, F., Valade, D., Lanteri-Minet, M. et al. Proposals for the organisation of headache services in Europe. Intern Emerg Med 3 (Suppl 1), 25–28 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-008-0189-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-008-0189-0