Abstract

Objective

Food addiction and binge eating share overlapping and non-overlapping features; the presence of both may represent a more severe obesity subgroup among treatment-seeking samples. Loss-of-control (LOC) eating, a key marker of binge eating, is one of the few consistent predictors of suboptimal weight outcomes post-bariatric surgery. This study examined whether co-occurring LOC eating and food addiction represent a more severe variant post-bariatric surgery.

Methods

One hundred thirty-one adults sought treatment for weight/eating concerns approximately 6 months post-sleeve gastrectomy surgery. The Eating Disorder Examination-Bariatric Surgery Version assessed LOC eating, picking/nibbling, and eating disorder psychopathology. Participants completed the Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS), the Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition (BDI-II), and the Short-Form Health Survey-36 (SF-36).

Results

17.6% met food addiction criteria on the YFAS. Compared to those without food addiction, the LOC group with food addiction reported significantly greater eating disorder and depression scores, more frequent nibbling/picking and LOC eating, and lower SF-36 functioning.

Conclusion

Nearly 18% of post-operative patients with LOC eating met food addiction criteria on the YFAS. Co-occurrence of LOC and food addiction following sleeve gastrectomy signals a more severe subgroup with elevated eating disorder psychopathology, problematic eating behaviors, greater depressive symptoms, and diminished functioning. Future research should examine whether this combination impacts long-term bariatric surgery outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Food addiction is a controversial construct characterized by craving and consumption of highly palatable foods (such as processed foods high in fat and sugar) resulting in a compulsive pattern of eating akin to behaviors commonly observed in substance use disorders [1]. Food addiction, assessed by the Yale Food Addiction Scale, is associated with obesity when examined dimensionally by symptom count (i.e., cravings) or dichotomously as exceeding a clinical threshold [2,3,4,5]. According to meta-analytic findings, relative to individuals with a normal body mass index (BMI), the rate of food addiction was greater than double within samples of individuals with overweight/obesity [5]. Specifically, the rate of food addiction among normal-weight participants was 11.1%, while the rate of food addiction among individuals in the overweight/obesity category was 24.9% [5]. Moreover, food addiction is related to objective measurements of adiposity such as the waist-to-hip ratio, percent body fat and trunk fat, and various health indicators, including high cholesterol, smoking, and decreased physical activity [6, 7]. Notably, the relationship between food addiction and obesity remained significant after adjusting for health factors, such as smoking, medication use, and physical activity [6].

Food addiction is also related to greater disordered eating, such as binge eating [3, 5, 8]. Definitions of binge eating and food addiction share some similar clinical features such as a loss-of-control overeating. Although binge eating disorder (BED) and food addiction often co-occur and might share some similar mechanisms, such as craving and emotion dysregulation, the constructs do not completely overlap [9]. For example, among a community sample of adults with overweight or obesity, 61.2% of those with BED met the criteria for food addiction, while only 27.6% of those with food addiction met the criteria for BED [4]. Thus, assessments measuring these constructs may capture partly or perhaps relatively unique subgroups. In addition, like food addiction, BED is associated significantly with greater BMI [10] and emerging data suggest that the co-occurrence of binge eating and food addiction might represent a more severe subgroup among treatment-seeking clinical samples of patients with obesity [11, 12]. Past research conducted in non-surgical samples of individuals with excess weight suggest that those with co-occurring food addiction and BED endorsed greater eating disorder psychopathology and psychosocial and psychiatric concerns than those without food addiction [2, 11,12,13]. These findings were consistent across different study groups of adults seeking treatment for binge eating in a specialty clinic setting [12], in a primary care setting [11], and among adolescents seeking treatment for obesity [13]; however, data from non-clinical convenience groups are mixed [2, 4]. For example, among adults with overweight/obesity recruited for an online study, the co-occurrence of BED and food addiction did not differ in clinical features relative to only food addiction (without BED), or only BED (without food addiction) [4]. Similarly, past findings examining the relationship between food addiction and weight loss treatment outcomes in non-surgical populations have been mixed [14,15,16]. Replication of these findings is warranted, and the prognostic significance of co-occurring food addiction and binge eating is not yet known, particularly with respect to weight loss.

Although bariatric surgery is an effective treatment for severe obesity, a substantial proportion of individuals have suboptimal weight outcomes following surgery [17]. Research identifying factors associated with poor long-term weight maintenance have led researchers to examine varying problematic eating behaviors after surgery. Although binge eating (defined traditionally as consuming unusually large amounts of food while experiencing a subjective sense of loss-of-control (LOC) post-surgery is uncommon due to physical restrictions imposed by surgery, LOC eating is one of the few consistent predictors of poorer weight loss outcomes in the post-operative period [18,19,20]. LOC eating is defined by the subjective experience of LOC or being unable to stop eating. The presence of LOC is generally viewed as the second key feature (in addition to size or quantity) of binge eating and is strongly associated with distress and impairment regardless of the size of a binge eating episode [21,22,23]. While several studies have examined post-operative LOC eating [19], very few studies have examined food addiction post-operatively [24]. Yanos and colleagues found that food addiction was associated cross-sectionally with weight regain after surgery, yet this finding was no longer significant when adjusting for post-surgical eating habits (e.g., night eating), depression, and other comorbidities [25]. We are only aware of two studies which have prospectively examined food addiction both before and after surgery [26, 27]; although these studies reported decreases in food addiction post-operatively, extremely high attrition rates greatly limit interpretation of the findings. Thus, very little is known with respect to symptoms of food addiction following bariatric surgery.

In summary, food addiction is common among individuals with excess weight and is related to problematic eating behaviors, but few studies have examined food addiction in post-operative bariatric surgery patients and no studies have examined the relationship of food addiction and LOC eating in a post-operative group of patients. The aim of this investigation was to examine the frequency of food addiction and associated clinical features among post-sleeve gastrectomy surgery patients with LOC eating. Based on previous findings in treatment-seeking groups, we hypothesized that (1) greater food addiction symptoms, measured dimensionally, would be associated with greater eating disorder psychopathology, depression, and poorer health-related quality of life, and (2) the group exceeding the clinical threshold of food addiction symptoms would report elevated psychopathology and disordered eating behaviors relative to the group without food addiction.

Methods

Participants

Participants included 131 adults seeking treatment for eating/weight concerns and reporting regular LOC eating during the past month. All participants were recruited from the Yale Bariatric/Gastrointestinal Surgery Center of Excellence, 4 to 9 months (M = 6.34, SD = 1.52) after sleeve gastrectomy surgery. Participants were either directly referred to the study by the bariatric team or responded to mailings or flyers soliciting patients with post-operative eating concerns. All assessments were conducted independently from the bariatric program. Individuals were eligible if they were between 18 and 65 years old and endorsed LOC eating (defined as having difficulty stopping eating, difficulty preventing themselves from eating, or experiencing a sense of LOC while eating regardless of quantity consumed, based on the Eating Disorder Examination interview) at least once weekly during the past month. Exclusion criteria were minimal and included effective medications known to influence eating or weight, substance dependence, or severe psychiatric illness requiring acute treatment.

Participants were predominately female (n = 120, 82.8%), and 51% of the total sample identified as White, not Hispanic, and 9.5% identified as Hispanic. On average, participants had a BMI of 37.7 kg/m2 (SD = 7.3) and 19.3% (SD = 7.1%) total weight loss (TWL). This investigation received approval from the University Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent.

Procedures and Assessments

Participants were assessed by doctoral-level clinicians with advanced training in eating and weight disorders and specific training in the assessment instruments. Height was measured using a stadiometer and weight was collected at intake using a high-capacity digital scale. Pre-surgical weight was obtained from the Bariatric Center of Excellence and all weight change calculations used measured weights.

All participants were assessed with the Eating Disorder Examination-Bariatric Surgery Version (EDE-BSV), a semi-structured interview which assesses eating disorder symptomology and overeating behaviors, adapted for bariatric surgery patients [28,29,30]. The EDE-BSV assesses standard EDE items including eating disorder symptomatology (such as shape and weight concerns) and LOC eating episodes, which were calculated based on the number of binge eating episodes (the sum of objective binge episodes and subjective binge episodes) endorsed during the past month, regardless of the amount consumed. We also examined episodes of picking/nibbling during the past month, a frequent problematic eating behavior observed among bariatric surgery patients [31]. An alternative three-scale structure of the EDE (Restraint, Overvaluation, Dissatisfaction) was recently supported in several confirmatory factor analytic studies and demonstrated superior psychometric properties in non-clinical and clinical samples [32,33,34]. The three-scale structure (EDE-Restraint, EDE-Overvaluation, and EDE-Dissatisfaction) and the EDE-Global Score were calculated for this investigation. Subscales on the EDE range from 0 to 6, with higher scores suggesting greater severity.

The Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS) is a 25-item self-report measure assessing symptoms of food addiction [1]. The YFAS assesses seven symptoms based on diagnostic criteria of substance use disorders from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) [35]. Symptoms from the DSM were modified to identify a perceived addiction to foods such as sweets, starches, salty snacks, fatty foods, and sugary drinks since undergoing bariatric surgery. Although food addiction is not a formal diagnosis in the DSM-5 or any classification system, the YFAS assesses food addiction based on proposed clinical criteria. The YFAS is scored both dimensionally (a “symptom” score, based on the number of symptoms endorsed) and dichotomously (a “diagnosis” by endorsing three or more symptoms and clinically significant impairment or distress), which suggests the clinical threshold of food addiction symptoms has been met [1]. The psychometric properties, including validity and reliability, of the YFAS have been examined in bariatric candidates and post-surgical patients [36,37,38,39,40].

The Beck Depression Inventory-Second Edition (BDI-II) is a widely used 21-item self-report measure assessing current depressive symptoms during the past 2 weeks [41]. Greater scores are indicative of greater depressive symptomatology.

The Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form Health Survey-36 (SF-36) [42] is a widely used measure of health-related quality of life in non-surgical and bariatric surgery studies [43] with strong psychometric validity and reliability [44, 45]. The SF-36 has two summary scores: physical health (SF-PFS) and mental health (SF-MFS). Scores on the SF-36 are transformed and computed as t scores with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. Higher scores on the SF-36 reflect better health-related quality of life.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed using SPSS 24.0. Bivariate correlations were conducted to examine the relationship between the YFAS symptom score and demographic variables (e.g., age), BMI, %TWL, eating disorder psychopathology (frequency of LOC eating episodes, EDE subscales), depression (BDI-II), and health-related quality of life (SF-36). A log transformation was used to adjust the skewness of the LOC eating episodes variable. A series of analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were conducted, adjusting for race, to compare differences between those who met the clinical threshold of food addiction (FA + LOC group) to those without food addiction (LOC) for continuous variables (e.g., age, %TWL).

Results

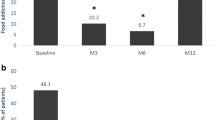

Of the overall participant group, n = 23 (17.6%) exceeded the clinical threshold of food addiction symptoms. The mean number of symptoms endorsed on the YFAS was 2.88 (SD = 1.83). Table 1 summarizes the frequency of specific symptoms endorsed on the YFAS.

Individuals with and without clinical levels of food addiction did not differ significantly in age nor was age significantly correlated with YFAS symptoms scores. Likewise, there were no differences in food addiction symptom scores when comparing men and women. Participants who identified as White reported greater YFAS symptoms (M = 3.23, SD = 1.86) when compared to participants who identified as not-White (M = 2.52, SD = 1.73), t(129) = − 2.24, p = .03.

Table 2 summarizes the bivariate correlations examining the YFAS symptom scores, weight-related variables, and clinical measures. Scores on the YFAS were correlated significantly with several indices of eating disorder symptomatology, including the EDE-Global Score, EDE-Overvaluation subscale, and EDE-Dissatisfaction subscale, but not with the EDE-Restraint subscale. YFAS symptom scores were also correlated significantly with depression symptoms (as assessed by the BDI-II) and the SF-MFS subscale, but not with the SF-PFS subscale. The YFAS symptom score was not associated with current BMI or %TWL. In addition, scores on the YFAS were significantly correlated with episodes of LOC eating (r = .47, p < .001) and picking and nibbling (r = .49, p ≤ .001). Adjusting for LOC eating (frequency) by conducting partial correlations revealed the same pattern of findings.

Table 3 includes the means and standard deviations of eating disorder symptomology overall and by group (participants with and without clinical levels of food addiction symptoms). ANCOVAs included race as a covariate given that there were significant differences in food addiction symptoms between White and not White individuals. Participants exceeding the clinical threshold of food addiction symptoms endorsed significantly greater EDE-Global scores, EDE-Overvaluation, and EDE-Dissatisfaction compared with participants without clinical levels of food addiction symptoms. Effect sizes ranged from small to medium. No differences in EDE-Restraint scores were observed between groups. Participants with food addiction endorsed significantly more frequent episodes of LOC eating and more frequent picking/nibbling episodes, with effect sizes in the medium range.

Discussion

Among post-operative sleeve gastrectomy patients with regular LOC eating, nearly 18% exceeded the clinical threshold of food addiction symptoms based on the YFAS. Greater food addiction symptoms were associated significantly with greater eating disorder psychopathology and eating behaviors, greater depressive symptoms, and poorer mental health–related quality of life, but not with either current BMI or %TWL post-surgery. A similar pattern of findings emerged when comparing groups based on clinical food addiction status such that co-occurring food addiction and LOC eating was broadly associated with greater psychopathology than LOC eating without food addiction. These findings of post-bariatric patients with LOC eating are consistent with findings from studies of treatment-seeking groups with overweight/obesity and/or BED [11,12,13].

Notably, nearly 18% of adults with LOC eating reported symptoms that are consistent with “food addiction” 6 months after sleeve gastrectomy surgery; this finding surpasses the low rates of food addiction (2–7%) observed in the bariatric literature 6–9 months post-surgery [26, 27]. Differences in rates may be due, in part, to methodological differences including timing of assessments and observational versus treatment-seeking designs. With respect to food addiction symptoms, nearly all participants in this participant group with LOC eating, not surprisingly, endorsed the symptom of being unable to cut down or quit eating, which is consistent with the definition of LOC eating. Over 40%, however, reported “tolerance” symptoms including the following: “Over time, I have found that I need to eat more and more to get the feeling I want, such as reduced negative emotions or increased pleasure” and “I have found that eating the same amount of food does not reduce my negative emotions or increase pleasurable feelings the way it used to” [1]. Both items suggest that individuals who endorse these items are struggling with emotion regulation, which may serve as an important treatment target. Furthermore, a sizeable minority endorsed the remaining symptoms such as continued use despite emotional and physical consequences, “withdrawal symptoms,” and impairment/distress due to overeating. A better understanding of this unique post-operative subgroup may help elucidate potential biological and psychological underpinnings associated with these more severe symptoms, particularly after bariatric surgery.

Whether this group with co-occurring food addiction and LOC eating requires unique treatments is unknown. Schulte, Grilo, and Gearhardt [9], in their review of potential shared and distinct mechanisms underlying food addiction and binge eating, discussed potential treatment implications for food addiction versus disordered eating. For instance, an addiction framework (i.e., harm-reduction or abstinence-based models) may be required for individuals who meet the criteria for “food addiction” versus traditional cognitive-behavioral therapy used to treat disordered eating. No study, however, has examined these different treatments for food addiction either with bariatric surgery or with different eating/weight disorders.

Clinically, it would be helpful to better understand the food types patients identify as “addictive” while answering the questions on the YFAS, particularly because many of the potentially addictive, highly palatable foods are meant to be avoided throughout the early post-operative period, and further, changes in taste perception [46] and cravings for sweets and fast foods are generally observed post-operatively [47]. Despite these potent changes in taste and craving after bariatric surgery, patients might be experimenting with the reintroduction of different food types 6 months post-surgery, with some individuals at greater risk or more susceptible to the addictive potential or reinforcement/reward quality of different foods. Future research is needed to better understand these issues among post-operative patients, which might differ from non-surgical groups with eating/weight concerns.

Finally, our findings do not provide evidence for the proposed “food addiction” construct, per se; however, replication of these findings across treatment-seeking study groups suggests that the YFAS items might help capture a subgroup of individuals with greater impairment. Indeed, food addiction, as currently conceptualized and assessed, may represent a more severe eating disorder variant as opposed to an addiction [48]. Future research is needed to disentangle these constructs and determine whether unique treatment needs are warranted.

Study limitations should be noted for context. This was a post-operative group of participants seeking treatment for eating and weight concerns approximately 6 months post-sleeve gastrectomy surgery and experiencing regular LOC eating; thus, this participant group may represent a more severe subgroup of individuals struggling with post-operative eating and weight. Findings may not generalize to other forms of bariatric surgery or to non-treatment-seeking individuals in the post-operative period. In addition, the original YFAS, which corresponds to DSM-IV-TR criteria [35], was used in the present study because the YFAS 2.0, which corresponds to DSM-5 [49] substance use criteria, was not available at the start of this study. Moreover, the study group with food addiction was small; future research with larger samples is needed to better understand the shared and distinct mechanisms of food addiction and LOC eating (or binge eating), particularly after bariatric surgery where data are scarce and evidence-based treatments for disordered/maladaptive eating patterns are lacking. Finally, the non-significant findings regarding YFAS and weight variables may be due to the short time elapsed after surgery; future research should examine whether early post-operative food addiction symptoms predict poorer long-term outcomes.

Conclusion

Nearly 18% of post-operative sleeve gastrectomy patients with LOC eating met the food addiction criteria. Co-occurrence of LOC eating and food addiction following sleeve gastrectomy signals a more severe subgroup with elevated eating disorder psychopathology and problematic eating behaviors as well as higher depressive symptoms and poorer functioning. Future research should examine whether this combination impacts long-term bariatric surgery outcomes. Early identification and treatments delivered post-surgically are needed to target the array of maladaptive eating behaviors which may present or reemerge following bariatric surgery.

References

Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, Brownell KD. Preliminary validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale. Appetite. 2009;52:430–6.

Davis C, Curtis C, Levitan RD, et al. Evidence that ‘food addiction’ is a valid phenotype of obesity. Appetite. 2011;57:711–7.

Gearhardt AN, Boswell RG, White MA. The association of “food addiction” with disordered eating and body mass index. Eat Behav. 2014;15:427–33.

Ivezaj V, White MA, Grilo CM. Examining binge-eating disorder and food addiction in adults with overweight and obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24:2064–9.

Pursey KM, Stanwell P, Gearhardt AN, et al. The prevalence of food addiction as assessed by the Yale Food Addiction Scale: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2014;6:4552–90.

Pedram P, Wadden D, Amini P, et al. Food addiction: its prevalence and significant association with obesity in the general population. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74832.

Flint AJ, Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR, et al. Food-addiction scale measurement in 2 cohorts of middle-aged and older women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99:578–86.

Burrows T, Kay-Lambkin F, Pursey K, et al. Food addiction and associations with mental health symptoms: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2018;31:544–72.

Schulte EM, Grilo CM, Gearhardt AN. Shared and unique mechanisms underlying binge eating disorder and addictive disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;44:125–39.

Udo T, Grilo CM. Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5-defined eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84(5):345–54.

Gearhardt AN, White MA, Masheb RM, et al. An examination of food addiction in a racially diverse sample of obese patients with binge eating disorder in primary care settings. Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54:500–5.

Gearhardt AN, White MA, Masheb RM, et al. An examination of the food addiction construct in obese patients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 2012;45:657–63.

Meule A, Hermann T, Kubler A. Food addiction in overweight and obese adolescents seeking weight-loss treatment. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2015;23:193–8.

Burmeister JM, Hinman N, Koball A, et al. Food addiction in adults seeking weight loss treatment. Implications for psychosocial health and weight loss. Appetite. 2013;60:103–10.

Chao AM, Wadden TA, Tronieri JS, et al. Effects of addictive-like eating behaviors on weight loss with behavioral obesity treatment. J Behav Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-018-9958-z.

Lent MR, Eichen DM, Goldbacher E, et al. Relationship of food addiction to weight loss and attrition during obesity treatment. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22:52–5.

Courcoulas AP, Christian NJ, Belle SH, et al. Weight change and health outcomes at 3 years after bariatric surgery among individuals with severe obesity. JAMA. 2013;310:2416–25.

Conceicao EM, Mitchell JE, Pinto-Bastos A, et al. Stability of problematic eating behaviors and weight loss trajectories after bariatric surgery: a longitudinal observational study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:1063–70.

Meany G, Conceicao E, Mitchell JE. Binge eating, binge eating disorder and loss of control eating: effects on weight outcomes after bariatric surgery. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2014;22:87–91.

White MA, Kalarchian MA, Masheb RM, et al. Loss of control over eating predicts outcomes in bariatric surgery patients: a prospective, 24-month follow-up study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:175–84.

Colles SL, Dixon JB, O’Brien PE. Loss of control is central to psychological disturbance associated with binge eating disorder. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16:608–14.

Goldschmidt AB. Are loss of control while eating and overeating valid constructs? A critical review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2017;18:412–49.

Vannucci A, Theim KR, Kass AE, et al. What constitutes clinically significant binge eating? Association between binge features and clinical validators in college-age women. Int J Eat Disord. 2013;46:226–32.

Ivezaj V, Wiedemann AA, Grilo CM. Food addiction and bariatric surgery: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2017;18:1386–97.

Yanos BR, Saules KK, Schuh LM, et al. Predictors of lowest weight and long-term weight regain among Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients. Obes Surg. 2015;25:1364–70.

Pepino MY, Stein RI, Eagon JC, et al. Bariatric surgery-induced weight loss causes remission of food addiction in extreme obesity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22:1792–8.

Sevincer GM, Konuk N, Bozkurt S, et al. Food addiction and the outcome of bariatric surgery at 1-year: prospective observational study. Psychiatry Res. 2016;244:159–64.

de Zwaan M, Hilbert A, Swan-Kremeier L, et al. Comprehensive interview assessment of eating behavior 18-35 months after gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6:79–85.

Devlin MJ, King WC, Kalarchian MA, et al. Eating pathology and experience and weight loss in a prospective study of bariatric surgery patients: 3-year follow-up. Int J Eat Disord. 2016;49:1058–67.

Mitchell JE, Selzer F, Kalarchian MA, et al. Psychopathology before surgery in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery-3 (LABS-3) psychosocial study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8:533–41.

Conceicao E, Mitchell JE, Vaz AR, et al. The presence of maladaptive eating behaviors after bariatric surgery in a cross sectional study: importance of picking or nibbling on weight regain. Eat Behav. 2014;15:558–62.

Grilo CM, Crosby RD, Peterson CB, et al. Factor structure of the eating disorder examination interview in patients with binge-eating disorder. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010;18:977–81.

Grilo CM, Reas DL, Hopwood CJ, et al. Factor structure and construct validity of the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire in college students: further support for a modified brief version. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48:284–9.

Machado PPP, Grilo CM, Crosby RD. Replication of a modified factor structure for the Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire: extension to clinical eating disorder and non-clinical samples in Portugal. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2018;26:75–80.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th text rev edn. American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, 2000.

Clark SM, Saules KK. Validation of the Yale Food Addiction Scale among a weight-loss surgery population. Eat Behav. 2013;14:216–9.

Meule A, Heckel D, Kubler A. Factor structure and item analysis of the Yale Food Addiction Scale in obese candidates for bariatric surgery. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2012;20:419–22.

Meule A, Muller A, Gearhardt AN, et al. German version of the Yale Food Addiction Scale 2.0: prevalence and correlates of ‘food addiction’ in students and obese individuals. Appetite. 2017;115:54–61.

Sevinçer GM, Konuk N, Bozkurt S, et al. Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the Yale food addiction scale among bariatric surgery patients. Anadolu Psikiyatri Derg. 2015;16:44–53.

Torres S, Camacho M, Costa P, et al. Psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of the Yale Food Addiction Scale. Eat Weight Disord. 2017;22:259–67.

Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory-second edition manual. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation; 1996.

Ware Jr JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83.

Kolotkin RL, Andersen JR. A systematic review of reviews: exploring the relationship between obesity, weight loss and health-related quality of life. Clin Obes. 2017;7:273–89.

McHorney CA, Ware Jr JE, Lu JF, et al. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994;32:40–66.

McHorney CA, Ware Jr JE, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247–63.

Ahmed K, Penney N, Darzi A, et al. Taste changes after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2018;28:3321–32.

Pepino MY, Bradley D, Eagon JC, et al. Changes in taste perception and eating behavior after bariatric surgery-induced weight loss in women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22:E13–20.

Lacroix E, Tavares H, von Ranson KM. Moving beyond the “eating addiction” versus “food addiction” debate: comment on Schulte et al. (2017). Appetite. 2018;130:286–92.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edn. Washington, DC, 2013.

Funding

This research was supported, in part, by NIH grant R01 DK098492.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This investigation received approval from the University Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. Outside the submitted work, Dr. Grilo reports grants from National Institutes of Health, consultant fees from Sunovion and Weight Watchers International, and royalties from Guilford Press and Taylor and Francis Publishing.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ivezaj, V., Wiedemann, A.A., Lawson, J.L. et al. Food Addiction in Sleeve Gastrectomy Patients with Loss-of-Control Eating. OBES SURG 29, 2071–2077 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-03805-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-019-03805-8