Abstract

Background

Smoking cessation had been typically associated with weight gain. So far, there are no reports documenting the relationship between weight loss after bariatric surgery and smoking habit. The objective of the study was to establish the relationship between weight loss and smoking habit in patients undergoing bariatric surgery and to analyze weight loss on severe smokers and on those patients who stopped smoking during the postoperative period.

Methods

All patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) with at least 2-year follow-up were included. Patients were divided into three groups: (A) smokers, (B) ex-smokers, and (C) non-smokers. Demographics and weight loss at 6, 12, and 24 months were analyzed. Smokers were subdivided for further analysis into the following: group A1: heavy smokers, group A2: non-heavy smokers, group A3: active smokers after surgery, and group A4: quitters after surgery. Chi-square test was used for statistics.

Results

One hundred eighty-four patients were included; group A: 62 patients, group B: 57 patients, and group C: 65 patients. Mean BMI was 34 ± 6, 31 ± 6, and 31 ± 6 kg/m2; mean %EWL was 63 ± 18, 76 ± 21, and 74 ± 22 % at 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively. The subgroup analysis showed the following composition: group A1: 19 patients, group A2: 43 patients, group A3: 42 patients, and group A4: 20 patients. Weight loss difference among groups and subgroups was statistically non-significant.

Conclusions

Our study shows that weight loss evolution was independent from smoking habit. Neither smoking cessation during the postoperative period nor smoking severity could be related to weight loss after LSG.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obesity is currently considered an epidemic disease that affects not only industrialized countries but also developing countries such as Argentina [1]. Obesity is now recognized as responsible for many other diseases and represents one of the main causes of preventable deaths [2].

Bariatric surgery represents the most effective treatment tool to achieve long-term weight loss with resolution or improvement of comorbidities in obese patients [3, 4]. Although the vast majority of patients will attain an adequate weight loss, a small percentage will not accomplish the expected results. Among others, patient’s characteristics, compliance to treatment, technical aspects, and follow-up quality could be responsible for these undesirable results [5].

It is well known that smoking cessation is intimately related to weight gain; however, the opposite relationship has not been studied: does weight loss have any influence in the smoking habit? So far, LSG has demonstrated good results in terms of weight loss and resolution/improvement of comorbidities [6]. There is increased evidence that LSG not only behaves as a restrictive procedure but also generates hormonal changes that would justify excellent results in the short and mid-term [7, 8].

For this reason, we decided to study the following aspects:

-

(1)

The influence of tobacco use on weight loss after bariatric surgery

-

(2)

The influence of weight loss on tobacco use

-

(3)

Results in terms of weight loss on different level of smokers

-

(4)

Results in terms of weight loss in patients who stopped smoking vs. those who continued smoking during the postoperative period

Material and Methods

A retrospective review of prospective collected data on patients undergoing LSG at Bariatric Surgery Program at Hospital Privado de Córdoba was performed. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Inclusion Criteria

-

Women and men ≥18 years old.

-

Periodic follow-up with the multidisciplinary team in patients 6 months out of surgery up to 24 months.

-

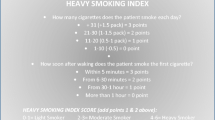

Completion of questionnaire over the phone, comparing weight and smoking habit before and after the surgery, using the HSI (Fig. 1) [9].

Patients meeting the criteria were divided into three groups: (A) smokers, (B) ex-smokers, and (C) non-smokers according to their tobacco use status at the time of surgery. Additionally, smokers were subdivided using the Heavy Smoking Index (HSI) for further analysis: group A1: heavy smokers and group A2: non-heavy smokers. Patients with a score ≥4 were considered heavy smokers. Smokers were also classified upon smoking status after surgery as follows: group A3: active smokers and group A4: quitters after surgery.

The following data were analyzed:

-

Gender

-

Age at the time of surgery

-

Time elapsed since surgery

Patients were evaluated anthropometrically using the following:

-

Body mass index (BMI) using the Quetelet equation (mass (kg)/height2 (cm). An electronic scale (SYSTEL®) was used.

-

Percentage excess weight loss (%EWL) was calculated as follows: ((initial weight-current weight)/(initial weight-ideal weight)) × 100.

BMI and %EWL were analyzed at 6, 12, and 24 months postoperative among groups A, B, and C; groups A1 and A2 were also compared among them, as well as groups A3 and A4.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square triple entry was used for %EWL comparison among the first three groups. Chi-square double entry was used for comparison between the remaining groups.

Results

Between January 2009 and June 2011, 184 patients underwent LSG at our Institution; all of them met the inclusion criteria for this study; mean age was 42 ± 10 years; there were 111 (60 %) women and 73 men (40 %), initial BMI was 46 ± 8 kg/m2. Mean follow-up was 22 ± 7 months. Patients were divided according to their smoking status, and distribution was as follows: group A (smokers): 62 patients, group B (ex-smokers): 57 patients, and group C (non-smokers): 65 patients. The percentage of patients available for follow-up was as follows: 184 (100 %) patients at 6 months, 153 (83 %) at 12 months, and 97 (53 %) at 24 months. Mean BMI was 34 ± 6, 31 ± 6, and 31 ± 6 kg/m2 at 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively; mean %EWL (excess weight loss) was 63 ± 18, 76 ± 21, and 74 ± 22 % at 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively (Table 1), (Figs. 2 and 3). The comparison between groups revealed the following results:

-

Group A: smokers (n = 62) showed a %EWL of 66 ± 17, 75 ± 19, and 68 ± 20 at 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively.

-

Group B: ex-smokers (n = 57) showed a %EWL of 58 ± 16, 73 ± 19, and 74 ± 21 at 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively.

-

Group C: non-smokers (n = 65) showed a %EWL of 66 ± 20, 77 ± 24, and 71 ± 24 at 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively.

Weight loss difference among groups was statistically non-significant at any time (Table 2).

Then, patients were again divided according to the HIS and their smoking status after surgery. The subgroup analysis showed the following composition: group A1 (heavy smokers): 19 patients and group A2 (non-heavy smokers): 43 patients (Table 3). Then, the smokers were again divided according to their smoking status after surgery: group A3 (active smokers): 42 patients and group A4 (quitters after surgery): 20 patients (Table 4). Again, weight loss difference was non-statistically significant across the groups. It is worth of mention that 20/62 (32 %) patients abandoned the habit after the operation. None of the ex-smokers relapsed. The non-smokers remained in the same status.

Discussion

Today, the relationship between smoking cessation and weight gain is well recognized. Still, there are scare data reporting the relationship among weight loss and smoking habit. “Symptom substitution” has been described in the literature as a phenomenon where an abusive behavior will be replaced by another one, if the main source is not treated appropriately [10]. Therefore, smoking habit could be a possible food substitute for patients who have undergone bariatric surgery.

The purpose of this study was to observe if weight loss could prompt any in changes in smoking habit and to observe the opposite relationship as well.

Some other reports investigated predicting factors of weight loss after bariatric surgery; many of them, specifically analyzed the influence of smoking habit at the time of surgery, which did not seem to be associated to an increased weight loss after surgery [11, 12]. Interestingly enough, nothing had been said about increased level of tobacco use when losing weight.

Heimberg et al. compared weight loss at 6 months after bariatric surgery in patients with history of substance abuse vs. patients with no history of any substance abuse. A better weight loss was observed in the group with history of substance abuse. However, this report does not mention details in particularly about tobacco use and does not investigate the possible increase of substance abuse as a consequence of weight loss either [13].

Lent et al. found in their study that smoking habit was not altered after bariatric surgery. This study only included patients undergoing gastric bypass. No difference was made between ex-smokers, heavy smokers, and non-heavy smokers [14].

We assessed tobacco consumption using two methods; the first one was based on chart review, where preoperative smoking habit was specifically investigated; the second method considered the smoking status after surgery using a simple questionnaire, easy to interpret, and reproducible. This questionnaire was based on HIS [9]; we recognize that patients might have a tendency to underestimate the level of consumption [15].

We evaluated 184 patients with good follow-up at 24 months. Patient’s distribution was equitable among groups. Difference in weight loss among the three groups was statistically non-significant. Next, patients were sorted according to their smoking status after the operation. Coincidentally with Lent [14], in our experience, weight loss did not increase the incidence of smoking habit in patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Moreover, 20/62 (32 %) patients abandoned the habit after the operation. When analyzing weight loss between these two groups, no difference was found between active smokers and quitters.

Furthermore, we studied the impact of heavy smoking vs. non-heavy smoking in weight loss. Again, no difference was found between these two groups: smoking habit did not have any influence in weight loss.

Conason et al. [16] published their series of 155 patients; they studied the possible increase in substance abuse when food intake decreased. Even though their follow-up was 50 % at 12 months, they noticed that there was a statistically significant increase in substance abuse in patients undergoing gastric bypass and adjustable gastric band. They did not report any data on patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy. It is worth of notice that these conclusions were based on the analysis of the entire group of substances. However, when data from tobacco use was analyzed separately, the same association could not be established, meaning that weight loss did not increase tobacco use.

These last three authors agreed in their publications that smoking habit and weight loss after bariatric surgery were independent variables. Consequently, bariatric surgery would be beneficial not only by decreasing the cardiovascular risk through the well-known mechanisms, but also by not increasing tobacco consumption as a way to canalize anxiety.

Conclusion

Our short-term results showed that tobacco consumption did not have any influence in weight loss after bariatric surgery. Similarly, weight loss did not influence the incidence of tobacco use either. Moreover, neither smoking cessation after bariatric surgery nor smoking severity did affect the results.

References

de Sereday MS, Gonzalez C, Giorgini D, et al. Prevalence of diabetes, obesity, hypertension and hyperlipidemia in the central area of Argentina. Diabetes Metab. 2004;30(4):335–9.

Vishwa Deep D. Adipose-immune interactions during obesity and caloric restriction: reciprocal mechanisms regulating immunity and health span. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84(4):882–92.

Dan E, Anna B, Nina B. Sleeve gastrectomy as a stand-alone bariatric operation for severe, morbid, and super obesity. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(41):1–190. 215–357, iii-iv.

Picot J, Jones J, Colquitt JL, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of bariatric (weight loss) surgery for obesity: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13(41):1–190.

Livhits M, Mercado C, Yermilov I, et al. Preoperative predictors of weight loss following bariatric surgery: systematic review. Obes Surg. 2012;22(1):70–89. doi:10.1007/s11695-011-0472-4.

6) Trastulli S, Desiderio J, Guarino S, Cirocchi R, Scalercio V, Noya G, Parisi A. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy compared with other bariatric surgical procedures: a systematic review of randomized trials. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013 Jun 12.

Terra X, Auguet T, Guiu-Jurado E, et al. Long-term changes in leptin, chemerin and ghrelin levels following different bariatric surgery procedures: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2013;23(11):1790–8.

Yousseif A, Emmanuel J, Karra E, et al. Differential effects of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic gastric bypass on appetite, circulating acyl-ghrelin, peptide YY3-36 and active GLP-1 levels in non-diabetic humans. Obes Surg. 2013;24(2):241–52.

Chabrol H, Niezborala M, Chastan E, et al. Comparison of the heavy smoking index and of the Fagerstrom test for nicotine dependence in a sample of 749 cigarette smokers. Addict Behav. 2005;30:1474–7.

Kazdin AE. Symptom substitution, generalization, and response covariation: implications for psychotherapy outcome. Psychol Bull. 1982;91(2):349–65.

Ferguson S, Al-Rehany L, Tang C, et al. Self-reported causes of weight gain: among prebariatric surgery patients. Can J Diet Pract Res. 2013;74(4):189–92.

Arterburn D, Livingston EH, Olsen MK, et al. Predictors of initial weight loss after gastric bypass surgery in twelve Veterans Affairs Medical Centers. Obes Res Clin Pract. 2013;7(5):e367–76.

Heinberg LJ, Ashton K. History of substance abuse relates to improved postbariatric body mass index outcomes. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6(4):417–21.

Lent MR, Hayes SM, Wood GC, et al. Smoking and alcohol use in gastric bypass patients. Eat Behav. 2013;14(4):460–3.

Lores Obradors L, Monsó Molas E, Rosell Gratacós A, et al. Do patients lie about smoking during follow-up in the respiratory medicine clinic? Arch Bronconeumol. 1999;35(5):219–22.

Conason A, Teixeira J, Hsu CH, et al. Substance use following bariatric weight loss surgery. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(2):145–50.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Informed Consent

Does not apply.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moser, F., Signorini, F.J., Maldonado, P.S. et al. Relationship Between Tobacco Use and Weight Loss After Bariatric Surgery. OBES SURG 26, 1777–1781 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-015-2000-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-015-2000-4