Abstract

Background

Attendance at bariatric surgery follow-up appointments has been associated with bariatric surgery outcomes. In this prospective study, we sought to examine psychosocial predictors of attendance at post-operative follow-up appointments.

Methods

Consecutive bariatric surgery patients (n = 132) were assessed pre-surgery for demographic variables, depressive symptoms, and relationship style. Patients were followed for 12 months post-surgery and, based on their attendance at follow-up appointments, were classified as post-surgery appointment attenders (attenders—attended at least one appointment after post-operative month 6) or post-surgery appointment non-attenders (non-attenders—did not attend at least one appointment after post-operative month 6). Psychosocial and demographic variables were compared between the attender and non-attender groups. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify significant predictors of attendance at post-bariatric surgery follow-up appointments.

Results

At 12 months post-surgery, 68.2 % of patients were classified as attenders. The non-attender group was significantly older (p = 0.04) and had significantly higher avoidant relationship style scores (p = 0.02). There was a trend towards patients in the non-attender group living a greater distance from the bariatric center (p = 0.05). Avoidant relationship style was identified as the only significant predictor of post-operative appointment non-attendance in the logistic regression analysis.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that avoidant relationship style is an important predictor of post-bariatric surgery appointment non-attendance. Recognition of patients' relationship style by bariatric surgery psychosocial team members may guide the delivery of interventions aimed at engaging this patient group post-surgery.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent practice guidelines for the support of bariatric surgery patients stress the importance of post-operative follow-up appointments. Unfortunately, several studies have shown that follow-up rates post-bariatric surgery have been a challenge. Reported attrition rates at 1 year following bariatric surgery have ranged from 0 to 53 % depending on the sample size and type of bariatric procedure performed [1–4]. In a recent meta-analysis comparing laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB), 2-year attrition rates were found to be 49.2 and 75.2 %, respectively [5]. Additional studies suggest that bariatric surgery attrition rates can vary widely, with study estimates over the last 10 years ranging from approximately 10 to 63 % [3, 6, 7]. Attendance at post-operative appointments is an important component of treatment adherence, and the poor follow-up rate is concerning given potential implications for surgical outcomes. Studies have shown that attendance at follow-up appointments is associated with improved weight loss outcomes and greater resolution of obesity-related medical co-morbidities [8–13].

A myriad of factors have been explored as predictors of attrition to bariatric surgery aftercare. A study of 375 patients mainly undergoing bariatric surgery found that patients who were younger, single, employed, had a lower BMI, and had insurance coverage were more likely to attend follow-up appointments [4]. Increasing travel distance away from the bariatric surgery center has also been cited as a predictor of poor post-operative follow-up [3, 8]. In a systematic review examining predictors of weight loss intervention attrition, two out of three studies in this review identified greater travel distance to the clinic as a predictor of aftercare attrition [14].

Relatively little research has directly examined psychosocial predictors of attendance at post-operative appointments in bariatric surgery populations. However, several studies have examined psychosocial predictors of bariatric surgery outcome. A recent systematic review of psychosocial predictors of surgical outcome identified social support and current or lifetime Axis I disorder as important predictors of weight loss following LRYGB [15]. Given that post-operative appointment non-adherence has been associated with a worse surgical outcome, it is possible that the psychosocial variables predicting a worse surgical outcome might also predict post-operative appointment non-attendance.

The impact of pre-operative depressive symptoms on bariatric surgery outcome has been examined in a number of studies but is currently considered inconclusive [15, 16]. Given that depression symptoms often make it difficult for patients to function (e.g., to complete activities of daily living or attend work, school, or social events), it seems plausible that depression could also make it difficult for bariatric patients to attend post-operative appointments. However, the aforementioned study examining predictors of attrition from bariatric surgery aftercare did not find a significant effect of depression [4]. This finding stands in contrast to the results of a large meta-analysis, which found depression to have a significant association with treatment adherence across a number of medical illnesses [14].

Social support has been found to be an important predictor of weight loss and quality of life following bariatric surgery [15]; however, a paucity of data exists on the effects of social support on attendance at post-operative appointments. Studies have shown that single marital status may increase post-operative adherence in some samples, which further complicates our understanding of the association between social support and post-operative appointment adherence. Individuals may not always utilize the social supports that are available to them. Thus, an individual's relationship (attachment) style is a more specific marker of social support because it characterizes how an individual accesses social support during illness events [17], such as after bariatric surgery. Relationship styles can be classified across a continuum between two insecure relationship styles, namely, avoidant and anxious styles. Individuals with a relationship style in the anxious spectrum will fear rejection and abandonment, and as a result, they will demonstrate behaviors consistent with dependence and need for emotional closeness. This dependence can include the bariatric surgeon and bariatric interdisciplinary team. Individuals with an avoidant relationship style have a desire for greater interpersonal distance, including with healthcare professionals, and have high levels of self-reliance despite the availability of post-operative supports. An avoidant relationship style can result in reduced help-seeking behaviors even in circumstances when help may be warranted (e.g., abdominal pain), and may delay patient presentation to the bariatric clinical team.

An avoidant relationship style has previously been associated with lower mental quality of life in bariatric surgery candidates [18]. Moreover, an avoidant relationship style has been associated with non-adherence to medical treatments in chronic medical conditions [19], poor treatment response [18], and increased mortality [20]. In light of these research findings in other medical populations, it is possible that an avoidant relationship style might also predict non-attendance at post-operative appointments in bariatric surgery populations.

The purpose of this study was to identify demographic and psychosocial predictors of attendance at post-operative appointments in a bariatric surgery population. We aimed to expand on previous studies by focusing on specific psychosocial predictors of bariatric surgery aftercare attendance, including depressive symptoms and relationship (attachment) style. Based on the findings of previous research, we hypothesized that older age, higher BMI, greater travel distance to the bariatric surgery center, depressive symptoms, and an avoidant relationship style would be associated with non-attendance at post-operative appointments over a 12-month period. Our study sought to identify psychosocial markers of post-operative aftercare attrition that can be used for early identification of at-risk patients who may be lost to follow-up.

Methods

Study Sample

Consecutively referred patients assessed at the Toronto Western Hospital (TWH) between December 1, 2009 and May 1, 2011 were eligible for this study. The Toronto Western Hospital is one of two bariatric assessment centers in a six-hospital University of Toronto Bariatric Surgery Collaborative and is a level 1A bariatric surgery center accredited by the American College of Surgeons. Patients were included in the study if they were between 18 and 65 years of age and had a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 or BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2, with at least one obesity-related co-morbidity. All participants provided informed consent prior to participating in the study.

LRYGB surgery was the routine surgical procedure performed unless a sleeve gastrectomy was surgically indicated. Details of the TWH pre-surgery assessment process have been previously described [21]. Suitability for bariatric surgery followed the National Institute of Health Guidelines [22]. The Research Ethics Board at the University Health Network approved this study as part of a larger prospective study.

Study Measures

Demographic data and pre-surgery study measures were collected at the first pre-surgery clinic appointment.

Demographic Variables

Demographic data were collected by program social workers and nurse practitioners and consisted of gender, age, and travel distance to the bariatric surgery center.

Anthropometric Measurements

All patients had their BMI measured by program dietitians at pre-surgery as well as 6- and 12-month post-operative follow-up appointments if they attended these appointments. Percent total weight loss (%TWL) was calculated at 6 and 12 months post-surgery.

Depression

Patients were screened for depression pre-surgery using either the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) or the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ9). The program moved to using the PHQ9 during the study period as a result of institutional changes in depression data collection [23]. As a result, patients in this study only completed one depression rating scale. Using cutoff scores established for bariatric populations, a BDI score ≥ 12 [24] or PHQ9 score ≥ 15 [23] was coded as a positive depression screen.

Relationship Style

Relationship (attachment) style was measured using the Experiences for Close Relationships scale (ECR-16), a 16-item scale that has been validated against the longer ECR-32 scale [25]. This measure describes a patient's relationship style during illness events and results in a total anxious (ECR-16anx) and total avoidant (ECR-16avoid) relationship style score based upon scoring of eight items using a seven-item Likert scale. Sample items include “I get frustrated when other people are not around as much as I would like” (anxious) and “I don't feel comfortable opening up to other people” (avoidant). Scores on the ECR-16 range from 8 to 56 for both anxiety and avoidant sub-scales, with higher scores representing greater relationship insecurity. The anxious and avoidant sub-scales have high internal reliability (Cronbach alpha > 0.81) and high test–retest reliability (Spearman rho 0.73–0.82) [25]. Individuals who are classified as being more anxious in their relationship style often have an excessive need for approval from others and experience intense distress when individuals in their support system are unavailable. Individuals with an avoidant relationship style fear dependence and have an excessive need to be self-reliant or independent. Higher ECR-16avoid relationship style scores have been previously associated with treatment non-adherence and treatment non-response in autoimmune hepatitis patients [26].

With respect to post-operative appointment attendance, patients were classified as either post-surgery appointment attenders (attenders) or post-surgery appointment non-attenders (non-attenders). A minimum of four follow-up appointments are scheduled during the first year of the post-operative phase: 1, 3, 6, and 12 months post-surgery. Additional follow-up appointments were provided depending on patient needs. If patients missed appointments, the routine procedure in the program was to call the patient to re-schedule an appointment. For the purpose of this study, patients were categorized as attenders if they attended a follow-up appointment within the 6- to 12-month period and non-attenders if they did not attend a single appointment between the 6- to 12-month period. We opted for this definition given that attendance at 3 months post-surgery in our program is approximately 92 % [27] and programs struggle with post-operative appointment adherence beyond 6 months post-surgery [4].

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences Statistics version 20.0. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze demographic data and psychiatric disorders. Categorical variables were compared between the attender and non-attender groups using chi-square tests. Normality of the data for continuous variables was tested using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. An independent t-test was used for normally distributed variables. Otherwise, a Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare continuous variables between the two groups.

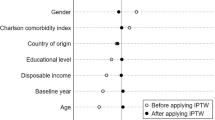

Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify significant predictors of attendance at post-bariatric surgery follow-up appointments. Covariates for logistic regression models included gender, age, travel distance, pre-surgery BMI, positive depression screen, and any variables achieving p < 0.05 when comparing attender and non-attender groups. The logistic regression outcome variable was patient classification as an “attender” versus “non-attender”. Gender, age, travel distance, and pre-surgery BMI were selected based upon previous studies highlighting these factors as potential predictors of non-attendance at post-bariatric follow-up appointments [3, 4]. Depression was also included in this model because it has previously been associated with poor treatment adherence in medical illnesses [28]. Statistical significance was determined with p < 0.05.

Results

A total of 132 patients were recruited for this study during the study period. A total of ten patients (7.6 %) underwent a sleeve gastrectomy—two of which were classified as non-attenders at the end of the 12-month follow-up. At 12 months post-surgery, 68.2 % (n = 90) were classified as attenders and the percent total weight loss was 33.8 ± 12.8 %. Nearly 80 % of the sample were female subjects and approximately 34 % screened positive for depression pre-surgery. Patients with a positive depression screen had significantly higher ECR-16avoid (29.6 ± 10.6 vs. 23.2 ± 10.6, p = 0.001) and ECR-16anx (27.4 ± 9.9 vs. 23.2 ± 10.5, p = 0.029) scores. A comparison of attenders and non-attenders on demographic and psychosocial variables is presented in Table 1.

Relative to the attender group, the non-attender group had significantly higher ECR-16avoid scores (attenders 23.22 ± 9.7 vs. non-attenders 27.8 ± 11.5, p = 0.019) and was significantly older (attenders 42.5 ± 10.2 vs. non-attenders 46.4 ± 8.8, p = 0.036). Attenders did not significantly differ from non-attenders on ECR-16anx scores or proportion of patients screening positive for depression. In addition, the difference in travel distance to the bariatric surgery center between attender and non-attender groups achieved borderline significance (attender 92.8 ± 144.4 vs. non-attender 105.6 ± 123.6, p = 0.05).

Weight measurements were available for 99 patients and 59 patients at 6 and 12 months post-surgery, respectively. There was no significant difference in %TWL at 6 months post-surgery between attender and non-attender groups (attender 34.61 ± 20.98 vs. non-attender 29.60 ± 18.09, p = 0.32). All 59 patients with %TWL data at 12 months post-bariatric surgery were in the attender group, preventing a comparison between attender and non-attender groups. The %TWL at 12 months post-bariatric surgery for the attender group was 35.59 ± 8.27.

Predictors of Attendance at Post-bariatric Surgery Follow-up Appointments

A multivariate logistic regression was used to predict attendance at post-bariatric surgery follow-up appointments using the following covariates: gender, positive depression screen, age, travel distance to the bariatric surgery center, pre-surgery BMI, and ECR-16avoid scores (see Table 2).

Model 1 examined a positive depression screen as the sole psychosocial predictor in this model and did not include ECR-16avoid scores. No predictors were found to be significant in this model. In model 2, ECR-16avoid scores were added to the predictors in model 1. The ECR-16avoid score was the only significant predictor of attendance at post-operative appointments (odds ratio (OR) =0.961 [confidence interval (CI) 0.924–0.998], p <0.05), with higher ECR-16avoid scores decreasing the odds of bariatric surgery aftercare appointment attendance. The remaining covariates, including a positive depression screen, were not significant predictors of attendance at post-operative appointments in model 2. Using this model, a five-point change in ECR-16avoid scores would yield a 19.5 % (OR = 0.0805) decrease in the likelihood of attending bariatric aftercare appointments.

Conclusion

An avoidant relationship (attachment) style was identified as the only significant predictor of attendance at post-operative follow-up appointments. Although gender, age, travel distance, and pre-surgery BMI have been found in previous studies to be significant predictors of post-operative follow-up [3, 4], these findings were not replicated in the current study. Interestingly, depression screening status was not associated with attendance at follow-up appointments. This finding replicates the results of another study examining adherence to post-operative appointments in bariatric surgery populations [4] but contradicts general findings from a meta-analysis on the negative effects of depression on treatment adherence in non-bariatric patient populations [29]. Given that depression symptoms have been shown to improve following bariatric surgery [30], one potential explanation for this finding is that individuals who screened positive for depression did not have depressive symptoms that were severe enough to interfere with appointment attendance during the post-operative follow-up phase. Avoidant relationship style may be a more stable predictor of post-operative appointment attendance.

Although a prior systematic review identified travel distance as a significant predictor of post-bariatric surgery follow-up attrition based upon two studies [3, 10], this association was not replicated in the current study. It is possible that the availability of travel grants from the government to cover health-related travel expenses and attempts to schedule all of the interdisciplinary appointments on the same day reduced the impact of travel distance on attendance at follow-up appointments in the current study.

This is the first research study to identify a relationship between avoidant relationship style, a feature of social support, and post-operative appointment non-adherence. An avoidant relationship style is considered a static factor when focused on an illness event, such as undergoing bariatric surgery. Although social support is often studied, relationship style provides specific detail on the actual utilization of social supports. Based upon this study, an avoidant relationship style may be a harbinger of appointment non-adherence following bariatric surgery. This finding is consistent with research conducted in other populations with chronic medical conditions, which has shown an association between an avoidant relationship style, poor treatment adherence, and treatment non-response [26].

Strengths of the study include a sample of consecutively referred bariatric surgery patients who were followed prospectively for 12 months post-surgery and the examination of a number of predictors of appointment attendance. However, limitations of the study must also be acknowledged. Although we examined the effects of a variety of demographic and psychosocial factors on appointment attendance following bariatric surgery, we did not contact non-attenders to inquire about the reasons for non-attendance at follow-up appointments. In addition, our study focused specifically on attendance at bariatric surgery follow-up appointments and could have benefited from greater inclusion of other types of non-adherence (e.g., dietary or exercise recommendations) and bariatric surgery outcomes. It would be informative for future studies to examine the relationship between appointment non-attendance and long-term surgical outcomes (e.g., weight loss and resolution of medical co-morbidities) and psychosocial outcomes (e.g., quality of life). Our study may not have had sufficient power to detect a statistically significant difference for other variables in the logistic regression analysis. This could explain why depression was not associated with poor adherence to follow-up appointments in our study. In addition, we could not account for additional bariatric-related care offered outside of our bariatric surgery program; however, this is unlikely given that the provincial bariatric surgery network was established in 2009 and most practitioners outside of the network were not familiar with bariatric surgery aftercare. Finally, our assessment of relationship style and depressive symptoms relied on self-report measures and could be vulnerable to reporting bias given that measures were completed within our bariatric surgery program as part of the pre-surgical assessment. Nonetheless, our rates of depression (as per depression screening instruments) were comparable to current depression rates in a study utilizing independent assessors [31].

Among a number of demographic and psychosocial predictors of adherence to bariatric surgery aftercare, avoidant relationship style was identified as the only significant predictor of non-adherence to post-operative appointments. Early identification of relationship style during pre-surgery assessment may be beneficial in prognosticating bariatric surgery aftercare adherence and mitigating non-adherence risks by delivering specific psychosocial interventions to individuals with an avoidant relationship style. Screening for relationship styles can be achieved using self-report rating scales such as the ECR-16 or the Relationship Questionnaire (RQ) (a briefer questionnaire). Although measures such as the RQ, ECR-12, or ECR-16 are brief tools that can be scored within minutes, the information gleaned from these questionnaires will need to be situated within the broader psychosocial context for each patient. Therefore, social workers, psychologists, or psychiatrists working in bariatric surgery programs are likely the best healthcare disciplines to review and interpret relationship style results from these self-report questionnaires. The results could be discussed with interdisciplinary team members in the program and could be used to inform a proactive team approach for patients who are highly avoidant in their relationship style.

Once patients are identified with an avoidant relationship style, bariatric clinicians can adapt their approach to patient care by respecting these patients' need for autonomy when possible and providing them with greater sense of personal control through motivational interviewing. Possible psychosocial interventions for patients with an avoidant relationship style might include longitudinal psychosocial supports integrated within bariatric surgery programs and care provided by a select number of providers who are familiar to the patient to facilitate engagement with patients with an avoidant relationship style. Further research investigating the efficacy of psychosocial interventions targeting this “difficult to engage” patient sub-group is warranted in order to address ongoing concerns about non-adherence to bariatric surgery aftercare programs given the implications for surgical outcome.

References

Nguyen NT, Slone JA, Nguyen XM, et al. A prospective randomized trial of laparoscopic gastric bypass versus laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for the treatment of morbid obesity: outcomes, quality of life, and costs. Ann Surg. 2009;250(4):631–41.

Schauer PR, Kashyap SR, Wolski K, et al. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy in obese patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(17):1567–76.

Lara MD, Baker MT, Larson CJ, et al. Travel distance, age, and sex as factors in follow-up visit compliance in the post-gastric bypass population. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2005;1(1):17–21.

Wheeler E, Prettyman A, Lenhard MJ, et al. Adherence to outpatient program postoperative appointments after bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4(4):515–20.

Garb J, Welch G, Zagarins S, et al. Bariatric surgery for the treatment of morbid obesity: a meta-analysis of weight loss outcomes for laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding and laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2009;19(10):1447–55.

Sugerman HJ, Sugerman EL, DeMaria EJ, et al. Bariatric surgery for severely obese adolescents. J Gastrointest Surg: Off J Soc Surg Aliment Tract. 2003;7(1):102–7. discussion 7–8.

Himpens J, Cadiere GB, Bazi M, et al. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Arch Surg. 2011;146(7):802–7.

Sivagnanam P, Rhodes M. The importance of follow-up and distance from centre in weight loss after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(10):2432–8.

Compher CW, Hanlon A, Kang Y, et al. Attendance at clinical visits predicts weight loss after gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2012;22(6):927–34.

DeNino WF, Osler T, Evans EG, et al. Travel distance as factor in follow-up visit compliance in postlaparoscopic adjustable gastric banding population. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2010;6(6):597–600.

Favretti F, Segato G, Ashton D, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in 1,791 consecutive obese patients: 12-year results. Obes Surg. 2007;17(2):168–75.

El Chaar M, McDeavitt K, Richardson S, et al. Does patient compliance with preoperative bariatric office visits affect postoperative excess weight loss? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7(6):743–8.

Dixon JB, Laurie CP, Anderson ML, et al. Motivation, readiness to change, and weight loss following adjustable gastric band surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2009;17(4):698–705.

Moroshko I, Brennan L, O'Brien P. Predictors of dropout in weight loss interventions: a systematic review of the literature. Obes Rev. 2011;12(11):912–34.

Sockalingam S, Hawa R, Wnuk S, et al. Weight loss following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: a systematic review of psychosocial predictors. Curr Psych Rev. 2011;7:226–33.

Livhits M, Mercado C, Yermilov I, et al. Behavioral factors associated with successful weight loss after gastric bypass. Am Surg. 2010;76(10):1139–42.

Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. New York: Basic Books; 1969.

Sockalingam S, Wnuk S, Strimas R, et al. The association between attachment avoidance and quality of life in bariatric surgery candidates. Obes Facts. 2011;4(6):456–60.

Ciechanowski P, Russo J, Katon W, et al. Influence of patient attachment style on self-care and outcomes in diabetes. Psychosom Med. 2004;66(5):720–8.

Ciechanowski P, Russo J, Katon WJ, et al. Relationship styles and mortality in patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(3):539–44.

Sockalingam S, Cassin S, Crawford SA, et al. Psychiatric predictors of surgery non-completion following suitability assessment for bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2013;23(2):205–11.

Conference NIH. Gastrointestinal surgery for severe obesity. Consensus Development Conference Panel. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(12):956–61.

Cassin S, Sockalingam S, Hawa R, Wnuk S, Royal S, Taube-Schiff M, Okrainec A. Psychometric properties of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) as a depression screening tool for bariatric surgery candidates. Psychosomatics. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.psym.2012.08.010.

Krukowski RA, Friedman KE, Applegate KL. The utility of the Beck Depression Inventory in a bariatric surgery population. Obes Surg. 2010;20(4):426–31.

Lo C, Walsh A, Mikulincer M, et al. Measuring attachment security in patients with advanced cancer: psychometric properties of a modified and brief Experiences in Close Relationships scale. Psychooncology. 2009;18(5):490–9.

Sockalingam S, Blank D, Abdelhamid N, et al. Identifying opportunities to improve management of autoimmune hepatitis: evaluation of drug adherence and psychosocial factors. J Hepatol. 2012;57(6):1299–304.

Mueller C, Okrainec A, Sockalingam S, et al. Bariatric surgical care delivery within a multidisciplinary psychosocial model may improve patient adherence and follow-up. Can J Surg. 2011;54:S60.

DiMatteo MR. Evidence-based strategies to foster adherence and improve patient outcomes. JAAPA: Off J Am Acad Physician Assist. 2004;17(11):18–21.

DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004;23(2):207–18.

de Zwaan M, Enderle J, Wagner S, et al. Anxiety and depression in bariatric surgery patients: a prospective, follow-up study using structured clinical interviews. J Affect Disord. 2011;133(1–2):61–8.

Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Levine MD, et al. Psychiatric disorders among bariatric surgery candidates: relationship to obesity and functional status. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:328–34.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our patients who participated in the study. We would also like to thank our Toronto Western Hospital Bariatric Interdisciplinary Team for their support and the Ministry of Health of Ontario for their ongoing psychosocial program funding.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sockalingam, S., Cassin, S., Hawa, R. et al. Predictors of Post-bariatric Surgery Appointment Attendance: the Role of Relationship Style. OBES SURG 23, 2026–2032 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-013-1009-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-013-1009-9