Abstract

Background

The BioEnterics Intragastric Balloon (BIB) has been considered an effective, less invasive method for weight loss, as it provides a permanent sensation of satiety. However, various non-randomized studies suggest BIB is a temporary anti-obesity treatment, which induces only a short-term weight loss. The purpose of this study was to present data of 500 obese who, after BIB-induced weight reduction, were followed up for up to 5 years.

Methods

The BioEnterics BIB was used, and remained for 6 months. At 6, 12, and 24 months post-removal (and yearly thereafter), all subjects were contacted for follow-up.

Results

From 500 patients enrolled, 26 were excluded (treatment protocol interruption); 474 thus remained, having initial body weight of 126.16 ± 28.32 kg, BMI of 43.73 ± 8.39 kg/m2, and excess weight (EW) of 61.35 ± 25.41. At time of removal, 79 (17%) were excluded as having percent excessive weight loss (EWL) of <20%; the remaining 395 had weight loss of 23.91 ± 9.08 kg (18.73%), BMI reduction of 8.34 ± 3.14 kg/m2 (18.82%), and percent EWL of 42.34 ± 19.07. At 6 and 12 months, 387 (98%) and 352 (89%) presented with weight loss of 24.14 ± 8.93 and 16.31 ± 7.41 kg, BMI reduction of 8.41 ± 3.10 and 5.67 ± 2.55 kg/m2, and percent EWL of 42.73 ± 18.87 and 27.71 ± 13.40, respectively. At 12 and 24 months, 187 (53%) and 96 (27%) of 352 continued to have percent EWL of >20. Finally, 195 of 474 who completed the 60-month follow-up presented weight loss of 7.26 ± 5.41 kg, BMI reduction of 2.53 ± 1.85 kg/m2, and percent EWL of 12.97 ± 8.54. At this time, 46 (23%) retained the percent EWL at >20. In general, those who lost 80% of the total weight lost during the first 3 months of treatment succeeded in maintaining a percent EWL of >20 long term after BIB removal: more precisely, this cutoff point was achieved in 83% at the time of removal and in 53%, 27%, and 23% at 12-, 24-, and 60-month follow-up.

Conclusion

BIB seems to be effective for significant weight loss and maintenance for a long period thereafter, under the absolute prerequisite of patient compliance and behavior change from the very early stages of treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Obesity remains an increasingly prevalent public health and socioeconomic problem of concern throughout Western society and elsewhere, since it results in both a significant reduction in quality of life, as well as in life expectancy. Obesity has clearly been associated with several serious comorbid conditions, including sleep apnea, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, lipid disorders and hepatic steatosis, ischemic heart disease, gallstones, degenerative joint disease leading to chronic pain syndromes and dysmotility, and certain cancers.

To reduce the incidence of morbidities related to obesity, the World Health Organization recommended a decrease of 5% to 15% of body weight maintained throughout time [1–3]. Of the multitude of aids on offer to achieve weight loss, many have little or no scientific merit. The plethora of dubious techniques advertised in the papers and magazines is a dramatic example of human ingenuity. Vast sums of money are being spent by a gullible public for little return. Lifestyle changes, including healthy dieting, physical activity and increased exercise, as well as, eventually, psychotherapeutic support remain the first-line therapy for successful weight loss, according to the National Institute of Health recommendations [4], possibly supplemented by medication as a second-line therapy [5, 6].

However, multiple studies indicate that such therapies have had limited sustainable effectiveness for the vast majority (>90%) attempting such therapy, resulting, after months or a year, to a drop back to the previous weight. When conservative methods fail, a different, more aggressive approach is needed, generally by means of surgery and often preceded by endoscopy [7–9].

The intragastric balloon has been considered an effective and reversible, less invasive, non-surgical method for weight loss, as it provides a continuous sensation of satiety that helps the ingestion of smaller portions of meals, thus facilitating maintenance of a low-calorie diet. It has been advocated both as a way to induce loss in non-morbid obesity or prior to bariatric surgery in the morbidly obese in order to decrease the operation-related morbidities and mortality, and in the obese with uncontrolled co-morbidities causing high-risk for anesthesia and bariatric surgery, or in the morbidly obese denied anesthesia and/or surgery [10–12], and, finally, to everyone who just need to achieve limited weight reduction either prior to surgery of whatever kind and for whatever reason or for esthetic purposes [13].

The aims of this study were to evaluate the effectiveness of the intragastric balloon and its impact on weight loss in a cohort of 500 obese Greek patients treated in a single center and to assess what happens during a 5-year follow-up period after balloon removal.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Over a 6-year period (December 2003 to April 2009), a total of 500 obese consecutive individuals were included in this study. Criteria for selection was either that they had consulted for weight reduction but refused surgery of any kind, or that, although obese, they failed to meet the IFSO standards for surgery [14].

A preliminary interview ascertained medical history, including previous attempts to lose weight, co-morbidities, and the impact of their obesity, both socially and psychologically. Prospective participants were also asked for a brief statement of their motivation to lose weight (e.g., to become more attractive (marriageable); to alleviate physical symptoms such as sleep apnea, diabetes, hypertension, and joint problems, and to increase their likelihood of becoming pregnant, etc.).

Their current weight status and body composition, assessed by bioelectrical impedance, were also recorded to provide estimation of BMI, initial excess weight (EW), and excessive weight loss percentage (percent EWL). A further interview with a dietician elicited dietary habits and introduced a new dietary regime.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients with obesity of hormonal or genetic cause; alcohol or drug abusers; or those with a known malignancy, pregnant, or desiring to become pregnant within the following 6 months were excluded. GI tract lesions, already known or identified at endoscopy, such as a large >5-cm hiatus hernia; grade C–D esophagitis; peptic ulcer; or esophageal/fundus varices were considered contraindications, and the individuals were excluded.

Technique

The BioEnterics Intragastric Balloon, Inamed® Corporation, Santa Barbara, CA, was used in all cases after an informed consent form was signed by all enrolled patients. All procedures were performed, on overnight fasted individuals, under midazolam conscious sedation (max, 5 mg), and by the same two fully trained endoscopists. Endoscopy was initially performed to rule out any GI abnormalities that would preclude the patient from participation. The balloon placement assembly was then inserted into the gastric fundus, and saline solution was used for balloon inflation, under direct endoscopic vision, according to the manufacturer’s instructions for insertion, described in detail elsewhere [11, 15]. A volume of 700 mL was used for patients with a BMI of more than 35 kg/m2 and 600 mL for individuals with a BMI between 30 and 35 kg/m2.

Patients then remained for 2 h in the recovery room, to verify full recovery from sedation, before discharge. Instructions were provided for a 3-day liquid diet, antiemetics, antispasmodics, and proton pump inhibitors, after which (or when vomiting and abdominal cramps or acid reflux subsided), patients were initially put on a semi-liquid diet, to be replaced gradually by a normal balanced diet of between 800–1,000 kcal for the remainder of the 6-month period. Medication was continued as required. Support was maintained in the form of a 24-h telephone helpline and ongoing dietary advice and adjustment as requested. At monthly interviews, the new dietary regime was reviewed, and an effort for re-education of eating habits was done; body weight loss and bioelectric impedance measurements were also performed, and advices were given.

At the end of the 6-month period, the gastric balloon was removed endoscopically. Removal was preceded by a 3-day clear-fluid diet, in order to minimize the risk of residual food entering the trachea. Deep intravenous anesthesia without tracheal intubation was used, with the patient in a lateral decubitus position. A double-channel endoscope and two long-jaw rat-tooth forceps facilitated the procedure.

At 6, 12, and 24 months post-removal (and every year thereafter), all subjects were contacted by phone and asked to participate in the pre-scheduled follow-up. Body weight (and body mass index) as well as bioelectric impedance were assessed.

Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± SD, unless otherwise indicated. Paired t test enabled statistical comparisons of data to be made within the treatment period. Differences of p less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

A total of 500 patients were initially enrolled in the study. Twenty six of them were excluded from the final assessment performed upon balloon removal on the sixth month, because of treatment protocol interruption (see causes of exclusion); 474 thus remained (Fig. 1)—133 males and 341 females aged 39.40 ± 11.5 years (range, 14 to 70). Obesity-related profiles of these 474 patients were as follows: mean body weight, 126.16 ± 28.32; mean BMI, 43.73 ± 8.39 kg/m2; mean initial EW, 61.35 ± 25.41.

Causes of exclusion from the final assessment were as follows: balloon removal prior to the end of the treatment period was requested and performed in 26 cases: 3 patients to proceed for bariatric surgery after a 2-month period and having lost between 18 and 30 kg; 11 patients being satisfied with the result of the weight loss achieved by the fourth month; 8 patients who refused to continue after copious vomiting for 10, 25, and 45 days post-insertion. There were two cases of sudden pregnancy, despite their having signed an informed understanding of the need for prevention. One further individual failed to experience any satiety; plain abdominal radiography and CT on month 2 after insertion revealed no evidence of balloon configuration, leading to the probable conclusion of accidental balloon rupture and uneventful evacuation through the anus. Finally, a few days prior to the programmed day of removal, one woman experienced violent vomiting, during which the balloon was expelled.

Upon completion of the 6-month period and on balloon removal day, a total of 474 patients were assessed. In summary, there was a mean body weight loss of 21.19 ± 10.3 kg or a 16.79% reduction, a mean BMI reduction of 7.39 ± 3.57 kg/m2 or 16.89%, and a percent EWL of 38.09 ± 20.18.

A total of 79 subjects, accounting for 17% of patients enrolled, were found to have an unsatisfactory weight loss, which means less than the cutoff of 20% in percentage of excess weight loss. This is attributable to poor compliance with the calorie-restricted diet and failure, despite repeated invitations, to attend the monthly follow-up appointments. Table 1 thus presents the data for only the remaining 395 who achieved their desired weight loss (percent EWL, >20). For these 395 obese individuals, there was a mean body weight loss of 23.91 ± 9.08 kg or an 18.73% reduction, a mean BMI reduction of 8.34 ± 3.14 kg/m2 or 18.82%, and a percent EWL of 42.34 ± 19.07.

The 395 subjects were then contacted for follow-up at 6, 12, and 24 months post-removal and then yearly thereafter. A total of 387 (98%) were presented at 6 months, 12 of whom had regained 3 ± 2 kg. A mean body weight loss of 24.14 ± 8.93 kg, a mean BMI reduction of 8.41 ± 3.10 kg/m2, and a percent EWL of 42.73 ± 18.87 at this time point gave the impression of a continuing effort for weight loss (Table 2).

One year after BIB removal from the 395 subjects contacted, a total of 352 (89%) were presented. The remaining 43 were as follows: 12 had regained weight at 6 months and another 2 were subjected to a second balloon insertion; 11 were operated on for obesity, and 18 were lost to follow-up. Data from these 352 subjects 12 and 24 months after removal are presented in Table 3. At 12 and 24 months, 187 out of 352 (53%) and 96 out of 352 (27%) continued to have a percentage of excess weight loss of more than 20 in relation to the 83% of individuals at the time of removal.

Since our material refers to a 6-year period from December 2003 to April 2009, 195 out of the total 474 individuals have—to date—concluded a 5-year follow-up period. At this time, 46 out of 195 (23%) had maintained a percent EWL of more than 20 (Table 4).

Analysis of the rate of weight loss during the 6-month treatment showed that 65% of the obese individuals had lost 80% of the total weight loss during the first 3 months. These 229 individuals who also had more than four out of the six monthly sessions with the dietitians and were also following a gym program were found to have much better results at the 12-month follow-up, in relation to the remaining 123 (35%). Comparative data are presented in Table 5. For these 229 subjects, data of weight loss maintenance during the 2-year follow-up are presented (Table 6).

Additionally, it must be mentioned that after a 2-year period, 42% (96 out of 229) continued to have a percent EWL of more than 20 in relation to 27% in the case of pooled data of the total 352 subjects after a 2-year period. Finally, the weight loss and maintenance data for only the 122 subjects (out of 229 who were found to have lost the 80% of the total weight loss during the first 3 months) having a 5-year follow-up are shown in Table 7.

Discussion

Obesity is largely caused by a lifestyle which increasingly involves little physical activity and excessive eating, particularly of attractive foods, high in fat and carbohydrates—especially simple sugars. It is also fast developing into our major medical problem, causing or exacerbating numerous diseases or conditions and both reducing quality of life and life expectancy, all leading to spiraling health costs.

An effective solution providing, by mechanical means, a sensation of satiety by gastric volume restriction, but being non-invasive, completely reversible and repeatable at any time, safe and of low cost, is thus clearly needed. At this moment, the intragastric balloon meets all the above criteria.

The BIB used in this study is a saline-filled smooth spherical balloon with a radio-opaque valve, designed to be “ideal,” according to the specifications defined by the consensus of international experts who met in 1987 [16]. To our knowledge, only a few studies involving such a large number of individuals treated in the same center are actually available for assessing the long-term evolution/results (up to 5 years) of weight loss following intragastric balloon treatment. This lack prompted us to estimate what happens to the cohort of 500 Greek obese subjects, operated on by the same two surgeon–endoscopists, in a long-term follow-up protocol. We observed an average body weight loss as high as 16.8% and a percent EWL of 38.09 ± 20.18 at the time of BIB removal and a progressive weight regain in a percentage of individuals at the 1- and 2-year follow-up, concluding an average weight loss of about 8% and percent EWL of 17.11 ± 8.40 at the end of the 2-year follow-up period. However, taking into consideration only the 65% of individuals who succeed in losing 80% of the total weight loss during the first 3 months of life with the balloon, they presented having a percent EWL of 51.98 ± 17.53 at time of removal and 20.64 ± 7.84 at the second year follow-up. This weight maintenance proved sufficient to preserve the benefits obtained for obesity-related co-morbidities and also to reduce mortality [17, 18].

Additionally, the weight loss and maintenance was accompanied by a significant improvement in quality of life [19], as was predicted in our material by a self-assessment questionnaire voluntarily completed by a huge number of individuals (ongoing study). This weight loss-related well-being encourages patients to maintain their modified lifestyle and food habits, acquired while the balloon was still in place in their stomach.

Although the majority of the obese progressively regain some weight, 27% of 352 or 42% of selected individuals as clarified above (96 out of 229) retained a percent EWL of more than 20 at the end of the 2-year follow-up. Thus, it is right to support the notion that the intragastric balloon may be useful in selected patients for long-term body weight maintenance, as has also been shown by other studies [20–22].

In the same manner, others have underlined the crucial role of the 10% cutoff of body weight loss percentage [18, 23], which was associated with an improvement in metabolic syndrome [17, 24]. In 33 patients who completed the study per protocol, weight loss was 25.6 kg (20.5%) after 1 year and 14.6 kg (11.4%) after 2 years; 55% maintained a weight loss of greater than 10%, while the proportion of patients with ≥10% baseline weight loss had dropped from 75% to 47% during the year following BIB removal [19, 25]. Herve at al [21] also found that only 56% of patients had ≥20% excess weight loss 1 year after BIB removal (compared to 74% at the time of BIB removal). In a recent publication, the proportion of subjects with ≥5% and with ≥10% baseline weight loss were 46 of 118 (39%) and 31 of 118 (26%), respectively, at the end of a follow-up of average 4.9 years (range, 3.4–6.7) [26].

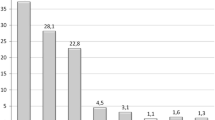

In a large series of 714 consecutive patients treated with one or two consecutive balloons, the initial mean BMI was 35.1 ± 8.3 kg/m2, and after BIB removal, it was 28.7 ± 5.1 kg/m2. After 24 months, 22% of patients regained the pre-BIB weight, 61% regained 45–50% of their pre-BIB weight, and 45 remained at the weight level after BIB removal ±2 kg [27]. Dastis et al. [28] demonstrated that intragastric balloon therapy was associated with weight loss maintenance at 2.5 years in a quarter of his 100 participants. He considered that successful BIB therapy must be defined as a loss of more than 10% of weight at baseline at 6 months which was maintained for 2.5 years, without bariatric surgery. In our material, speaking in percentages of EWL > 20, we can say that from the total of 500 obese subjects, this cutoff point was achieved in 83% at the time of removal, in 53% (187 out of 352) at the time of the 12-month follow-up, in 27% (96 out of 352) at the time of the 24-month follow-up, and in 23% (46 out of 195) at the time of the 60-month follow-up.

According to the review of 22 non-randomized studies performed by Dumonceau [29], among 4,371 BIB patients led to an absolute weight loss averaging 17.8 kg (range, 4.9–28.5), corresponding to BMI changes of 4.0–9.0 kg/m2 and resulting in resolved or improved co-morbidities in 52–100% of patients.

In another synchronous review from 15 studies that summarized data from up to 3,608 patients, Imaz et al. [18] estimated a weight loss of 14.7 kg; initial weight loss of 12.2%; BMI lost, 5.7 kg/m2; and percent EWL, 32.1% excess weight lost, but they do mention that the data are heterogeneous, since not all given parameters refer to all the studies. For example, only 9 out of 15 studies (3,200 patients) were given results related to BMI loss, and only 2 studies provided data on maintenance weight lost 1 year after treatment [17, 20].

Sallet et al. [30] concluded in a multicenter study from Brazil that 85 patients (34% of the 250 who completed 6 months after BIB removal) who returned for follow-up had maintained a substantial weight reduction, even if their 6-month percent EWL (50.9 ± 28.8) was significantly lower than that of the time of removal (57.4 ± 26.4%). In another 17 patients who were followed 18 months after BIB removal (11% of the 158 who completed 18 months after BIB removal) showed a percent EWL of 56.9 ± 36.5, which was not significantly different from their percent EWL of 66.1 ± 28.0 at the time of removal. However, results in patients who did not come back remain speculative. Considering the data in general, the high percentage of individuals not presented for follow-up represents an indigenous disadvantage for the statistics and raises real questions in relation to the credibility of the results.

The advantage of our study over others is that it is a single-center study of 500 obese subjects who were followed up for up to 5 years. The second point that needs to be underlined is the finding of massive weight loss early enough upon BIB placement in relation to weight loss maintenance. Indeed, 65% (n = 229) of the obese individuals who were found to have lost the 80% of the total weight loss during the first 3 months of treatment presented much better results at the 12- and 24-month follow-up, in relation to the remaining 35% (n = 123). Namely, they keep a percent EWL of 33.88 ± 12.68 at 12-month versus 16.23 ± 3.45 of the other group, respectively (Table 7), reduced to 20.64 ± 7.84 at 24 months and to 17.01 ± 7.67 at 60 months (112 patients—Table 7). These findings can be translated into a percentage of as high as 42% of subjects continuing to have a percent EWL of more than 20 after a 2-year period versus 27% in the case of pooled data of the total 352 subjects. Thus, we are suggesting that when patients agree to multidisciplinary treatment and change their behavior as early as from the beginning of the treatment, they can achieve a significant weight loss and maintain it for more than 1 to 2 years after BIB removal.

Similarly, Al-Momen et al. [31] state that most of the weight loss with the BIB occurred during the first 3–4 months. Totte et al. [32] further hypothesize this effect being related to stomach adaptation to the balloon, since their patients showed a good evolution of BMI from 37.7 to 32 kg/m2, which reflects 50.8% excess weight loss after 6 months. The main weight reduction was achieved in the first 3 months, with a 48.6% EWL, after which only a moderate additional weight reduction was achieved to 50.8% EWL.

However, the total efficacy of the intragastric balloon may be related to the self-conducted adaptation of the patient’s diet after the period of initial intolerance. This “starter” effect is of interest because initial weight loss is positively correlated with long-term weight maintenance [29, 30]. Furthermore, a multidisciplinary approach involving nutritionists and psychologists facilitates the consolidation of new eating routines induced by the balloon, while a physiotherapist will help in training the patients, especially those with locomotor disorders, in regular exercise

In our material, since the Greek patient is not so familiar with the need for psychotherapy sessions used in other countries, we used the term “strong desire” for self-support psychotherapy. At the initial interview, we asked the obese to describe in a few words the main reason for strongly desiring weight loss and we then used this phrase at every follow-up session to inspire them to continue the effort for weight loss or loss maintenance.

Although the latest Cochrane systematic review of BIB in the treatment of obesity states that it is a temporary anti-obesity treatment, which induces only a short-term weight loss [33], our data retrieved from 500 obese subjects treated with the BioEnterics intragastric balloon and followed up for up to 5 years support show that they can achieve a significant weight loss and maintain it for more than 1 to 2 years after BIB removal provided that they comply with a multidisciplinary treatment regime and change their behavior as early as from the beginning of treatment. This weight maintenance proved sufficient to reduce metabolic syndrome and prevent obesity-related co-morbidities. Taking into consideration only individuals who achieved a weight loss of 80% of the total weight loss during the first 3 months of life with the balloon (consisting of 65% of the material studied), they succeeded in maintaining a percent EWL of more than 20 after a 2-year period at a rate of 42% and a percent EWL of 17.01 ± 7.67 after 5 years in a rate of 30%. This enables us to conclude that BIB insertion for morbid obesity seems to be a safe and effective, non-invasive treatment under the absolute prerequisite of patient compliance and behavior change from the beginning of the treatment. Otherwise, BIB treatment might be used as a bridge toward a definitive bariatric operation immediately or whenever a patient presents with weight regain.

References

WHO. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation on obesity. Geneva: WHO; 1998

Allison DB, Fontaine KR, Manson JE, et al. Annual deaths attributable to obesity in the United States. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;1999(282):1530–8.

Health benefits of weight loss. In: www.maso.org.my/spom/chap4.pdf.

National Institutes of Health. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults—the evidence report. National Institutes of Health. Obes Res 1998; 6: 51S–209S.

Bays HE. Current and investigational antiobesity agents and obesity therapeutic treatment targets. Obes Res. 2004;12:1197–211.

Waseem T, Mogensen KM, Lautz DB, et al. Pathophysiology of obesity: why surgery remains the most effective treatment. Obes Surg. 2007;17:1389–98.

Franz MJ, VanWormer JJ, Crain AL, et al. Weight-loss outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1755–67.

Avenell A, Brown TJ, McGee MA, et al. What interventions should we add to weight reducing diets in adults with obesity? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of adding drug therapy, exercise, behaviour therapy or combinations of these interventions. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2004;17:293–316.

Curioni CC, Lourenço PM. Long-term weight loss after diet and exercise: a systematic review. Int J Obes. 2005;29:1168–74.

Rossi A, Bersani G, Ricci G, et al. Intragastric balloon insertion increases the frequency of erosive esophagitis in obese patients. Obes Surg. 2007;17:1346–9.

Kotzampassi K, Eleftheriadis E. Intragastric balloon as an alterantive procedure for morbid obesity. Ann Gastroenterol. 2006;19:285–8.

Doldi SB, Micheletto G, Di Prisco F, et al. Intragastric balloon in obese patients. Obes Surg. 2000;10:578–81.

Kotzampassi K, Shrewsbury AD. Intragastric balloon: ethics, medical need and cosmetics. Dig Dis. 2008;26:45–8.

Melissas J. IFSO guidelines for safety, quality, and excellence in bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2008;18:497–500.

Wahlen CH, Bastens B, Herve J, et al. The BioEnterics Intragastric Balloon (BIB): how to use it. Obes Surg. 2001;11:524–7.

Schapiro M, Benjamin S, Blackburn G, et al. Obesity and the gastric balloon: a comprehensive workshop. Tarpon Springs, Florida, March 19–21, 1987. Gastrointest Endosc. 1987;33:323–7.

Crea N, Pata G, Della Casa D, et al. Improvement of metabolic syndrome following intragastric balloon: 1 year follow-up analysis. Obes Surg. 2009;19:1084–8.

Imaz I, Martínez-Cervell C, García-Alvarez EE, et al. Safety and effectiveness of the intragastric balloon for obesity. A meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2008;18:841–6.

Mui WL, Ng EK, Tsung BY, et al. Impact on obesity-related illnesses and quality of life following intragastric balloon. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1128–32.

Mathus-Vliegen EM, Tytgat GN. Intragastric balloon for treatment-resistant obesity: safety, tolerance, and efficacy of 1-year balloon treatment followed by a 1-year balloon-free follow-up. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:19–27.

Herve J, Wahlen CH, Schaeken A, et al. What becomes of patients one year after the intragastric balloon has been removed? Obes Surg. 2005;15:864–70.

Mion F, Gincul R, Roman S, et al. Tolerance and efficacy of an air-filled balloon in non-morbidly obese patients: results of a prospective multicenter study. Obes Surg. 2007;17:764–9.

Deitel M. How much weight loss is sufficient to overcome major co-morbidities? Obes Surg. 2001;11:659.

Spyropoulos C, Katsakoulis E, Mead N, et al. Intragastric balloon for high-risk super-obese patients: a prospective analysis of efficacy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:78–83.

Mathus-Vliegen EM. Intragastric balloon treatment for obesity: what does it really offer? Dig Dis. 2008;26:40–4.

Dumonceau JM, François E, Hittelet A, et al. Single vs repeated treatment with the intragastric balloon: a 5-year weight loss study. Obes Surg. 2010;20:692–7.

Lopez-Nava G, Rubio MA, Prados S, et al. BioEnterics® Intragastric Balloon (BIB®). Single ambulatory center Spanish experience with 714 consecutive patients treated with one or two consecutive balloons. Obes Surg. 2011;21:5–9.

Dastis NS, François E, Deviere J, et al. Intragastric balloon for weight loss: results in 100 individuals followed for at least 2.5 years. Endoscopy. 2009;41:575–80.

Dumonceau JM. Evidence-based review of the Bioenterics intragastric balloon for weight loss. Obes Surg. 2008;18:1611–7.

Sallet JA, Marchesini JB, Paiva DS, et al. Brazilian multicenter study of the intragastric balloon. Obes Surg. 2004;14:991–8.

Al-Momen A, El-Mogy I. Intragastric balloon for obesity: a retrospective evaluation of tolerance and efficacy. Obes Surg. 2005;15:101–5.

Totté E, Hendrickx L, Pauwels M, et al. Weight reduction by means of intragastric device: experience with the bioenterics intragastric balloon. Obes Surg. 2001;11:519–23.

Fernandes M, Atallah AN, Soares BG, Humberto S, Guimarães S, Matos D, Monteiro L, Richter B. Intragastric balloon for obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD004931

Conflict of Interest

All contributing authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kotzampassi, K., Grosomanidis, V., Papakostas, P. et al. 500 Intragastric Balloons: What Happens 5 Years Thereafter?. OBES SURG 22, 896–903 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-012-0607-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-012-0607-2