Abstract

Background

Beside complications like band migration, pouch-enlargement, esophageal dilation, or port-site infections, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) has shown poor long-term outcome in a growing number of patients, due to primary inadequate weight loss or secondary weight regain. The aim of this study was to assess the safety and efficacy of laparoscopic conversion to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGBP) in these two indications.

Methods

A total of 25 patients, who underwent laparoscopic conversion to RYGBP due to inadequate weight loss (n = 10) or uncontrollable weight regain (n = 15) following LAGB, were included to this prospective study analyzing weight loss and postoperative complications.

Results

All procedures were completed laparoscopically within a mean duration of 219 ± 52 (135–375) min. Mean body weight was reduced from 131 ± 22 kg (range 95–194) at time of the RYGBP to 113 ± 25, 107 ± 22, and 100 ± 21 kg at 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively, which results in excess weight losses (EWL) of 28.3 ± 9.9%, 40.5 ± 12.3%, and 50.8 ± 15.2%. No statistically significant differences were found comparing weight loss within these two groups.

Conclusion

RYGBP was able to achieve EWLs of 37.6 ± 16.1%, 48.5 ± 15.1%, and 56.9 ± 15.0% at 3, 6, and 12 months following conversion, respectively, based on the body weight at LAGB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the last decade, laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) has gained fast-growing popularity in the community of European and Australian bariatric surgeons [1], mostly due to the simplicity and safety of this strictly restrictive bariatric procedure. Today, LAGB is performed by a large number of surgeons worldwide. Besides good results in the first postoperative period [2, 3], the long-term results point out the limits of this procedure. Esophageal dilation [4], pouch-enlargement [5], or band migration [6] frequently necessitates band removal. Besides these band-related complications, a growing number of patients present with poor primary weight loss or secondary weight regain [7].

Due to the superior weight loss in short-term and long-term follow-up [8], the more effective improvements of comorbidities, especially diabetes [8, 9], and the nowadays established laparoscopic approach, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGBP) has replaced LAGB as the most commonly performed bariatric procedure in the majority of the Austrian high-volume bariatric centers. As rebanding has shown only limited success in reinducing weight loss [10, 11], the switch from LAGB as a restrictive procedure to RYGBP as a combined restrictive–malabsorptive procedure is recommended in LAGB failure [11].

The aim of this study was to assess the safety and efficacy of laparoscopic conversion from LAGB to RYGBP. As primary inadequate weight loss and secondary weight regain following satisfying weight reduction might represent two completely different categories of patients, we compared weight loss following laparoscopic conversion from LAGB to RYGBP in these two indications (Fig. 1).

Materials and Methods

From April 2004 to October 2007, a total of 25 patients (24 females, 1 male) with a mean BMI at time of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGBP) of 47.6 ± 7.7 kg/m2 (range: 34–70) underwent laparoscopic band explantation and simultaneous establishment of a gastric bypass for inadequate weight loss or weight regain following LAGB. A total of three other patients were excluded due to conversion to open surgery at gastric banding. Major pouch-enlargement or band migration [12] was ruled out by preoperative workup consisting in upper GI contrast series and gastroscopy.

LAGB was performed according to the “perigastric” technique [13] in 10 patients and, since 2002, in the “pars-flaccida” technique [14] in 15 patients. Mean BMI and body weight at time of LAGB were 51.0 ± 8.1 kg/m2 (range: 37.6–75.1) and 140 ± 275 kg (range 110–207), respectively (Table 1). Patients from our department (n = 17) underwent band adjustments under fluoroscopy “on demand,” starting with a routine first band filling at 6 weeks postoperatively. Following LAGB, a total of five patients underwent band repositioning (n = 2) or rebanding (n = 3) due to pouch-enlargement. Mean maximum weight loss was 31 ± 19 kg (range 3–62) and mean maximum percent excess weight loss (%EWL) following LAGB was 39.9 ± 26.0% (range 0–97.8).

According to the Reinhold criteria [15], patients were classified into two groups: inadequate weight loss (group A) with a maximum EWL of less than 25% and weight regain (group B), as indication for revision surgery was defined as primary success and secondary weight gain of more than 10 kg based on the minimum weight achieved by LAGB, not controllable by multiple band adjustments under fluoroscopy. Conversion to LRYGBP was performed at mean 53 (range: 17–118) months following LAGB. Mean BMI and body weight at time of surgery were 47.6 ± 7.7 kg/m2 (range: 37–70) and 131 ± 22 kg (range 95–194), respectively.

From April 2004 to May 2006, the establishment of the gastro-jejunostomy was performed in the “circular stapling technique” with transoral anvil placement [16], using the 25-mm circular stapler (Covidien, Hamilton, Bermuda). In May 2006, we changed to the “linear stapling technique” [17] using a linear Endo-GIA, blue cartridge 3.5 mm (Covidien). Weight loss is expressed as percentage of EWL, based on the Metropolitan Life Tables [18].

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and range. A p value <0.05 was considered to be significant. Differences in EWL comparing patients with inadequate weight loss and secondary weight regain patients were analyzed using the paired sample t test. Statistical analysis [19] was performed using the SSPS statistical package, version 11.0 (SSPS).

Results

Conversion from LAGB to LRYGBP was performed due to inadequate weight loss in 10 (40%) patients (group A) and for weight regain in 15 (60%) patients (group B). Upper GI tract contrast study revealed remarkable esophageal dilation in five (33%) of the 15 patients in group B. All procedures were completed laparoscopically within a mean total operative time of 219 ± 52 (range: 135–375) min including port removal and laparoscopic adhesiolysis and removal of the band. These results are comparable to other published series [20]. Stay in the hospital was similar in both groups, with a median length of stay of 5 days (range 4–20).

We observed a total of four major complications, consisting of two port-site hernias on days 3 and 175; one stricture at the gastro-jejunostomy successfully dilated at day 89. Late fistula at the level of the gastro-jejunal anastomosis was diagnosed in one patient at 13 months following LRYGBP, causing a subhepatic abscess beneath the left lobe of the liver. She underwent CT-guided drainage and temporary endoscopic placement of a Niti-S-Stent® (Taewong Medical, Seoul, South Korea) to seal the fistula.

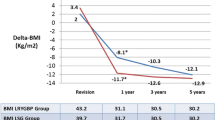

Mean body weight was reduced from 131 ± 22 kg (range 95–194) at time of the LRYGBP to 113 ± 25, 107 ± 22, and 100 ± 21 kg at 3, 6, and 12 months, respectively, which results in EWLs of 28.3 ± 9.9%, 40.5 ± 12.3%, and 50.8 ± 15.2% and a BMI decrease from 47.6 ± 7.7 kg/m2 (range: 37–70) to 35.4. ± 6.6 kg/m2 (range: 25–52) at 12 months postoperatively. No statistically significant differences were found comparing %EWL of patients with inadequate weight loss or uncontrollable weight regain following LAGB (Table 2). Based on body weight at LAGB, LRYGBP was able to achieve %EWLs of 37.6 ± 16.1%, 48.5 ± 15.1%, and 56.9 ± 15.0% at 3, 6, and 12 months following conversion, respectively.

Discussion

This study shows that laparoscopic band removal and subsequent establishment of a RYGBP can be safely performed simultaneously in cases of inadequate weight loss or weight regain after LAGB. Furthermore, weight loss following RYGPB, defined as %EWL, is comparable in these two indications.

For patients choosing a bariatric procedure, LAGB provides a wide range of advantages, such as proven low morbidity and mortality [21], short hospital stay, and potential reversibility. For many surgeons, the surgical simplicity, as no intestinal anastomosis must be established, makes LAGB the procedure of choice.

On the one hand, LAGB is performed today in many hospitals by a growing number of surgeons. On the other hand, adequate postoperative patient care is not always available, as many surgeons performing LAGB are not specialized or profoundly experienced in bariatric surgery. In the postoperative follow-up, fluroscopy [22] is essential for accurate band inflation and diagnosis of esophageal dilation or pouch dilations.

As an even minor esophageal dilation or subclinical pouch enlargement remains unrecognized, the chances of reversibility might diminish, resulting in a therapeutically dilemma: stringed band adjustment will worsen preband dilation, but band deflation, as indicated in these situations, will instantly lead to major weight gain. Thus, suboptimal band adjustment increases the risk for weight regain in the later postoperative course. Possible reasons for primary inadequate weight loss may be unrecognized sweet-eating behavior, poor general complicance, or an inability to adapt the eating behavior to the band. These patients might have been better candidates for RYGBP or duodenal switch (DS).

Weight regain after primary successful weight reduction might be caused by pouch-enlargement, esophageal dilation, or intractable vomiting necessitating complete band deflation, but also by unexpected changes in the eating behavior, as some high-volume eaters turn to secondary sweet-eaters in the late postoperative course. Some patients report “eating against the band” or “eating to, and even beyond the limit,” which might also induce pouch-enlargement or esophageal dilation in the longer run.

As we still lack reliable preoperative predictors [23, 24] for the success of LAGB, patient selection for this procedure is still based on empirical data. In our center, LAGB is recommended only for compliant high-volume eaters, without sweet-eating behavior, diabetes, gastro-esophageal reflux, or esophageal motility disorders. Therefore, we set indication for LAGB to be more stringent today than we did in the last decade.

Compared to LAGB, LRYGBP provides better results in the short- and long-term weight reduction [25, 26], a lower incidence of reoperations in the longer run [27], and a superior effect on the comorbidities. However, in the early postoperative course, a higher incidence of complications is reported [28] like leakage or strictures at the gastro-jejunostomy [29, 30]. Therefore, in selected patients, we still recommend LAGB as the least invasive bariatric procedure.

Rebanding can be taken into consideration as a revisional operation after LAGB failure, especially in LAGB patients with “hardware” problems like band leakage, tube disconnection, or port site complications, if the patient was able to achieve adequate weight loss after the first band placement and has no esophageal dysmotility. Nevertheless, Gagner and Gumbs [31] do not recommend rebanding because of the lack of data showing successful weight reduction afterwards. In our limited, single-center experience, nearly all patients complain about a remarkable poorer band sensation after rebanding, compared to the first banding, which might contribute to the poor results of rebanding.

Weber et al. [11] compared laparoscopic rebanding to conversion to RYGBP and found significantly better BMI reduction in the RYGBP group as BMI decreased from 42.0 to 31.8 kg/m2 within 12 months postoperatively in a series of 32 patients. This corresponds to our findings in BMI reduction in this series of 25 patients.

Different opinions exist on whether a subsequent gastric bypass should be performed in the same operation following band removal. Chronic inflammatory changes of the gastric wall, induced by the gastric band, might reduce safety of the establishment of the gastro-jejunostomy, resulting in a higher incidence of leakage at this site. Our data show that a two-step procedure consisting of band removal followed by LRYGBP later on is not indicated in simply “functional” inadequate weight loss or weight regain. In contrast to Suter et al. [32], who reported safe simultaneous open conversion to RYGBP in a series of 11 patients with band migration, we prefer the two-step approach with band removal by gastroscopy [33, 34] and delayed laparoscopic RYGBP in this indication.

Besides conversion to RYGBP, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and DS have been published as revisional procedures after failed LAGB. Bernate et al. [35] presented a series of eight LSGs following LAGB; five of these patients achieved an EWL of 57% at 1 year. No complications or conversions were observed in this study. In another recent study, Lalor et al. [36] presented a total of 13 conversions from LAGB to LSG in a series of 164 LSG patients. As DS has proven superior weight loss compared to LAGB, RYGBP, and sleeve gastrectomy [3], this operation [37, 38] might be the “procedure of choice” in the superobese presenting with LAGB failure, as also recommended by Gagner et al. [31] for these patients.

Patients who never achieved adequate weight loss after LAGB might be candidates for a combined restrictive–malabsorptive procedure, such as LRYGBP. Weight regain after successful weight loss might have reasons totally different from primary inadequate weight loss. Weight regain is also observed following RYGBP [39–41]. As initial weight loss following RYGBP is suggested to be based more on the restrictive effect than on the mild malabsorption, patients who gained weight after the strictly restrictive LAGB might therefore be prone to also regaining weight after RYGBP. In this case, these patients should better undergo a more malabsorptive procedure, such as the DS. In this study, presenting short-time results for conversion to RYGBP for primary inadequate weight loss and weight regain, we observed no significant differences in the efficacy of weight reduction for these two indications. As weight regain occurs mainly after the first 2 years, long-term follow up will show the incidence of “weight regain relapse” in LAGB—“weight regainers” following conversion to RYGBP. Further prospective studies should be carried out focusing on the optimal revisional procedure comparing rebanding, conversion to RYGBP, or DS for different types of LAGB failure and patient characteristics.

References

Buchwald H, Williams SE. Bariatric surgery worldwide 2003. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1157–64.

Ren CJ, Weiner M, Allen JW. Favorable early results of gastric banding for morbid obesity: the American experience. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:543–6.

Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724–37.

Dargent J. Esophageal dilatation after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: definition and strategy. Obes Surg. 2005;15:843–8.

Chevallier JM, Zinzindohoue F, Douard R, et al. Complications after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for morbid obesity: experience with 1,000 patients over 7 years. Obes Surg. 2004;14:407–14.

Angrisani L, Furbetta F, Doldi SB, et al. Lap Band adjustable gastric banding system: the Italian experience with 1863 patients operated on 6 years. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:409–12.

Suter M, Calmes JM, Paroz A, Giusti V. A 10-year experience with laparoscopic gastric banding for morbid obesity: high long-term complication and failure rates. Obes Surg. 2006;16:829–35.

White S, Brooks E, Jurikova L, Stubbs RS. Long-term outcomes after gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2005;15:155–63.

Christou NV, Sampalis JS, Liberman M, et al. Surgery decreases long-term mortality, morbidity, and health care use in morbidly obese patients. Ann Surg. 2004;240:416–23; discussion 23–4.

Lanthaler M, Mittermair R, Erne B, et al. Laparoscopic gastric re-banding versus laparoscopic gastric bypass as a rescue operation for patients with pouch dilatation. Obes Surg. 2006;16:484–7.

Weber M, Muller MK, Michel JM, et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, but not rebanding, should be proposed as rescue procedure for patients with failed laparoscopic gastric banding. Ann Surg. 2003;238:827–33; discussion 33–4.

Niville E, Dams A, Vlasselaers J. Lap-Band erosion: incidence and treatment. Obes Surg. 2001;11:744–7.

Favretti F, Cadiere GB, Segato G, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding (Lap-Band): how to avoid complications. Obes Surg. 1997;7:352–8.

Dargent J. Pouch dilatation and slippage after adjustable gastric banding: is it still an issue? Obes Surg. 2003;13:111–5.

Reinhold RB. Critical analysis of long term weight loss following gastric bypass. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1982;155:385–94.

Matthews BD, Sing RF, DeLegge MH, et al. Initial results with a stapled gastrojejunostomy for the laparoscopic isolated roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Am J Surg. 2000;179:476–81.

Shope TR, Cooney RN, McLeod J, et al. Early results after laparoscopic gastric bypass: EEA vs GIA stapled gastrojejunal anastomosis. Obes Surg. 2003;13:355–9.

Deitel M, Greenstein RJ. Recommendations for reporting weight loss. Obes Surg. 2003;13:159–60.

Klingler A. Statistical methods in surgical research—a practical guide. Eur Surg. 2004;36:80–4.

Mognol P, Chosidow D, Marmuse JP. Laparoscopic conversion of laparoscopic gastric banding to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a review of 70 patients. Obes Surg. 2004;14:1349–53.

Chapman AE, Kiroff G, Game P, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in the treatment of obesity: a systematic literature review. Surgery. 2004;135:326–51.

Wiesner W, Schob O, Hauser RS, Hauser M. Adjustable laparoscopic gastric banding in patients with morbid obesity: radiographic management, results, and postoperative complications. Radiology. 2000;216:389–94.

Busetto L, Segato G, De Marchi F, et al. Outcome predictors in morbidly obese recipients of an adjustable gastric band. Obes Surg. 2002;12:83–92.

Kinzl JF, Schrattenecker M, Traweger C, et al. Psychosocial predictors of weight loss after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1609–14.

Mognol P, Chosidow D, Marmuse JP. Laparoscopic gastric bypass versus laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in the super-obese: a comparative study of 290 patients. Obes Surg. 2005;15:76–81.

Weber M, Muller MK, Bucher T, et al. Laparoscopic gastric bypass is superior to laparoscopic gastric banding for treatment of morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2004;240:975–82; discussion 82–3.

Jan JC, Hong D, Pereira N, Patterson EJ. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding versus laparoscopic gastric bypass for morbid obesity: a single-institution comparison study of early results. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:30–9; discussion 40–1.

Biertho L, Steffen R, Ricklin T, et al. Laparoscopic gastric bypass versus laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: a comparative study of 1,200 cases. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;197:536–44; discussion 44–5.

Almahmeed T, Gonzalez R, Nelson LG, et al. Morbidity of anastomotic leaks in patients undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Arch Surg. 2007;142:954–7.

Suggs WJ, Kouli W, Lupovici M, et al. Complications at gastrojejunostomy after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: comparison between 21- and 25-mm circular staplers. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:508–14.

Gagner M, Gumbs AA. Gastric banding: conversion to sleeve, bypass, or DS. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1931–5.

Suter M, Giusti V, Heraief E, Calmes JM. Band erosion after laparoscopic gastric banding: occurrence and results after conversion to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2004;14:381–6.

Weiss H, Nehoda H, Labeck B, et al. Gastroscopic band removal after intragastric migration of adjustable gastric band: a new minimal invasive technique. Obes Surg. 2000;10:167–70.

Regusci L, Groebli Y, Meyer JL, et al. Gastroscopic removal of an adjustable gastric band after partial intragastric migration. Obes Surg. 2003;13:281–4.

Bernante P, Foletto M, Busetto L, et al. Feasibility of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as a revision procedure for prior laparoscopic gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2006;16:1327–30.

Lalor PF, Tucker ON, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Complications after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:33–8.

de Csepel J, Quinn T, Pomp A, Gagner M. Conversion to a laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion with a duodenal switch for failed laparoscopic adjustable silicone gastric banding. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech, A. 2002;12:237–40.

Peterli R, Donadini A, Peters T, et al. Re-operations following laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg. 2002;12:851–6.

Bessler M, Daud A, DiGiorgi MF, et al. Adjustable gastric banding as a revisional bariatric procedure after failed gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2005;15:1443–8.

Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2683–93.

Gobble RM, Parikh MS, Greives MR, et al. Gastric banding as a salvage procedure for patients with weight loss failure after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc. 2007. doi:10.1007/s00464-007-9609-x.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Langer, F.B., Bohdjalian, A., Shakeri-Manesch, S. et al. Inadequate Weight Loss vs Secondary Weight Regain: Laparoscopic Conversion from Gastric Banding to Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. OBES SURG 18, 1381–1386 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-008-9479-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-008-9479-x