Abstract

Summary

Using a Danish Register cohort of 86,039 adult new allopurinol users and propensity score matched controls, we found that gout requiring allopurinol prescription was associated with an increased fracture risk.

Purpose

Gout, an acute inflammatory arthritis, is common and associated with elevated serum urate, obesity and high alcohol consumption. The mainstay of therapy is the urate-lowering agent, allopurinol. Here, we report the relationship between allopurinol prescription and fracture in a large registry population.

Methods

We established a Danish Register cohort of 86,039 adult cases (new allopurinol users) and 86,039 age, sex and propensity score matched controls (not exposed to allopurinol or with a gout diagnosis), with no diagnosis of malignancy in the year prior.

Results

We found a modest adjusted effect of allopurinol prescription on major osteoporotic fractures (hazard ratio (HR) 1.09, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.05–1.14, p = 0.04) and on hip fractures (HR 1.07, 95 % CI 1.11–1.14, p < 0.001), robust to adjustment for confounding factors (age, sex, comorbidity, medication use). Associations were stronger in men than women, and among incident allopurinol users whose gout diagnosis had been confirmed by at least one hospital contact. Prespecified subanalyses by filled dose of allopurinol (mg/day in first year of prescription) showed increased hip and major fracture risk in women in the highest allopurinol dose grouping only, while a less strong dose effect was evident for fracture rates in men.

Conclusion

Gouty arthritis requiring allopurinol is associated with an excess risk of major or hip fracture, with an allopurinol dose effect evident in women such that women taking the highest doses of allopurinol—suggestive of more severe disease—were at increased risk relative to women taking lower doses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gout is the most prevalent form of inflammatory arthritis worldwide causing substantial morbidity and impaired quality of life [1–3]. The prevalence of gout increases with age in association with its primary risk factor, sustained hyperuricaemia. In the prevention of acute gout attacks, allopurinol is the mainstay of therapy. The association of gout with poor bone health and fracture risk is hence of great public health importance, given both the high prevalence of this condition and widespread use of allopurinol therapy, particularly at older ages.

Risk of osteoporotic fracture is greater among individuals with low bone density, and frequent fallers. Lifestyle and anthropometric characteristics of gout patients may contribute to fracture risk in a number of ways. Although one might speculate that bone mineral density (BMD) might be raised in gout patients because the metabolic syndrome and its constituent elements are common in gout patients [4, 5], and obesity is generally considered protective against osteoporosis [6], recent reports have suggested that morbid obesity might be associated with an excess fracture risk, particularly at the ankle [7, 8]. Furthermore, conditions associated with high levels of inflammation, with stimulation of the inflammatory cascade and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Il-1, IL-10, IL-6, TNF-α) are well-recognised to cause both localised and generalised osteoporosis [8, 9]. In addition, gout patients may be inactive because of recurrent gouty flares or may have an increased alcohol intake [10]. A recent meta-analysis found a relative risk for a diagnosis of gout of 2.64 (95 % CI 2.26–3.09) for heavy drinking, classified as three or more alcoholic drinks per day, when compared with subjects who consumed minimal amounts of alcohol [11]. Finally, falls may be more common in gout sufferers with lower limb arthritis.

Gouty attacks are triggered when a raised serum urate provokes urate crystal deposition in the joints, leading to a fall in serum urate levels. Serum urate levels will be reduced by allopurinol treatment if compliance is good. While previous studies have examined the association of serum urate with fracture and observed conflicting results (the MrOS study found a reduced risk of non-spine fracture and higher BMD among men with higher serum urate concentrations [12], while a study that used the Cardiovascular Health Study found a U-shaped relationship between hip fracture and serum uric acid in men but not women) [13]. In spite of in vitro models suggesting that allopurinol can reduce bone resorption [14] and promote bone formation [15], to our knowledge, no previous research has addressed the relationship between allopurinol use and bone health.

The aim of this study was therefore to extend and inform this area of research by utilising a very large Danish registry to study fracture rates among a population of men and women filling one or more allopurinol prescriptions, a subset of whom had a hospital diagnosis of gout, to assess direction of association between allopurinol prescription and fracture risk in a very large population of both sexes.

Materials and methods

As already discussed, gout patients who suffer recurrent attacks are typically prescribed allopurinol, a xanthine oxidase inhibitor that lowers urate concentrations. Use of this medication is widespread in Denmark with 1.5 % of women and 4.5 % of men aged 65+ being allopurinol users (Data from Danish National Board of Health for 2012, www.medstat.dk accessed July 2014). However, as in many other countries, adherence and compliance with this medication is low, with many gout suffers filling only one prescription. Colchicine is not available in Denmark.

This study is an observational study from Denmark using data from several Danish registers. The study population are selected by identifying all individuals who had at least one allopurinol prescription in the period from 1995 to 2011 in the Danish National Prescription Registry (DNPR). DNPR covers the entire nation´s population and contains all prescriptions issued by prescribers, general practitioners or specialists since 1994 [16].

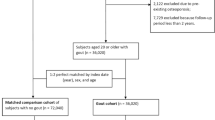

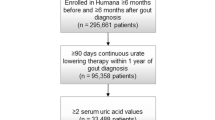

In this study, the index date was defined as the date of the first prescription for allopurinol or matching date for background control subjects. We used 1995 as a run-in year to identify prevalent users of allopurinol and to identify the date of first allopurinol prescription for the years 1996–2011 to find all new users of allopurinol. Each incident user was first assigned up to ten age- and gender-matched control subjects from the Danish civil registration system (comprising all Danish citizens) who were not allopurinol users. This was used for basic descriptive analysis of the allopurinol cohort (table available from the authors on request). Patients were then further matched on quintiles of propensity score to identify a more highly matched 1:1 control population for assessment of outcomes by conditional Cox proportional hazards models in an open cohort design. A calliper of 0.2 was applied. The design of the study is shown in Fig. 1.

Variables used as baseline descriptors and as candidates for inclusion in the propensity score model included ICD-10 hospital diagnoses (inpatient and outpatient) from 1995 to 2012, Charlson index components derived from hospital contacts and any prior major osteoporotic fractures. These variables were extracted from the Danish National Patient Registry, which contains discharge diagnoses of hospitalised patients indicating the main medical reason for diagnostic procedures or treatment [17]. Number of other medications in the past year, prednisolone use in the past year, use of HRT, use of osteoporosis drugs, use of antihypertensives, statins, NSAIDs, insulin, oral antidiabetics and anticoagulants (all: any use in the past year) were extracted from the DNPR. In addition to these variables, we also adjusted for ICD-10 diagnoses indicative of chronic kidney disease or diabetes in our final models. Analyses were restricted to adults over the age of 18 years. The Danish Civil Persons register was used to access dates of death in order to censor Cox regressions on the date of death or the date of end of study (31 December 2012), whichever was the earlier date.

Because allopurinol may be used as an adjunct to chemotherapy in malignant disease, patients with a recent cancer diagnosis (in the past 12 months before the first allopurinol prescription) were excluded from both the gout cohort and the potential control population prior to matching.

The project was approved by Statistics Denmark (project 704127) and by the National Board of Health for data access. The study was not a clinical trial and ethics committee approval was not required.

Results

Baseline characteristics and matching

The initial study population consisted of 1,043,861 individuals over the age of 18 years, 104,026 allopurinol users and 939,835 controls (Fig. 1) selected from a population of 113,131 incident allopurinol users and 1,396,640 potential population controls.

The propensity score matching identified a highly matched (1:1) population with 172,078 individuals (86,039 in each group, Table 1). The mean age was 63 years and ranged from 18 to 103 years, one third were women and two thirds were men. The distribution of comorbidity among allopurinol users and controls was more balanced than before propensity score matching though modest residual imbalances that were nominally statistically significant remained and had to be controlled for in the Cox regressions. Hence, prior fractures were slightly more prevalent in allopurinol users (15 vs 14 %, p < 0.001) and this was also true for major osteoporotic fractures (6.5 vs 5.7 %, p < 0.001). Use of osteoporosis drugs was very low in both groups, 1.6 % in allopurinol users and 1.2 % in control subjects (p < 0.001).

Incident fractures

A total of 13,071 (15 %) allopurinol users and 12,170 (14 %) controls sustained fractures; the number of major osteoporotic fractures was 5565 (6.5 %) and 4885 (5.7 %), respectively. Incidence rates stratified by age and sex for the two groups are shown in Table 2. Table 3 shows the association of allopurinol prescription with fracture before and after adjustment for relevant potential confounders (prior fracture, renal disease, comorbidities, Charlson index, drug history). We found a modest adjusted effect of allopurinol prescription on major osteoporotic fractures (hazard ratio (HR) 1.09, 95 % CI 1.05–1.14, p = 0.04); and on hip fractures (HR 1.07, 95 % CI 1.11–1.14, p < 0.001). Effects were stronger in men than women.

Disease severity

Among patients who were incident allopurinol users and who also had at least one hospital contact with a gout diagnosis, suggestive of more severe gout compared with patients who were exclusively managed in private practice, (about 20 % of allopurinol users, median number of allopurinol prescriptions 12 vs 6 in non-hospital group), we found stronger associations (Table 4). After adjustment for relevant potential confounders (prior fracture, renal disease, comorbidities, Charlson index, drug history), we found an increased adjusted effect of allopurinol prescription on major osteoporotic fractures (HR 1.26, 95 % CI 1.15–1.39, p < 0.001) and on hip fractures (HR 1.21, 95 % CI 1.04–1.41, p = 0.02). Again, results were stronger in men than women. In a sensitivity analysis to address any potential confounding effect of renal disease, we included chronic kidney disease in our confounder panel; we also identified patients on particularly low doses of allopurinol (100 mg daily) as this may reflect impaired renal function. These extra analyses made little difference to our findings; no significant interactions were found, and stratification confirmed the same effect size and direction.

Dose response analysis

Finally, we performed prespecified subanalyses to consider the filled dose of allopurinol as milligrams per day over the first year of therapy, including pauses in treatment. We took this approach rather than basing our calculations on the total cumulative dose up to the time of fracture to remove the possibility that our results would be biased by differences in cumulated time, because individuals who fracture early would, on average, fill fewer allopurinol prescriptions in the time period between the index date and the date of fracture even if allopurinol had no true relation to fracture risk. Including allopurinol used after the fracture event as a predictor would have been flawed of course. Table 5 shows the risk of fracture according to tertile of allopurinol exposure. It shows that fracture risk was elevated in the women who received the highest allopurinol dose [hip 1.22 (95 % CI 1.06–1.410, p = 0.007; major fracture 1.13 (95 % CI 1.03–1.24) p = 0.01) but a dose effect was less apparent in men.

Discussion

We have observed increased rates of fracture among patients in receipt of allopurinol for a presumed diagnosis of gout, with elevated fracture rates among women in the highest tertile of drug prescription relative to their peers but less of a dose effect evident among men. This relationship between allopurinol and fracture risk remains after adjustment for other medications, including steroids and osteoporosis treatments, and for comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease. When we confined our analysis to individuals who also had a hospital diagnosis of gout (no doubt the severe end of the spectrum) our observations were strengthened. Our findings suggest that gout requiring allopurinol may be a risk factor for fracture.

There are, of course, a number of limitations to our study. Perhaps the most significant is the lack of serum urate levels available to us. We used propensity score matching to achieve balancing of potential confounders as much as possible, but the potential of residual confounding remains, particularly with regard to dietary modifications made after a diagnosis of gout. We have no information on body habitus, lifestyle factors such as alcohol consumption, nor falls information. In any study such as this, there will be a trade-off between the size of the population and the exact matching between cases and controls. The choice we made was based on retaining a large sample population which were comparatively well (though not perfectly) matched. However, this analysis of a very large, representative, well-characterised data set has allowed us to report a clear excess of fracture among patients receiving allopurinol for gouty arthritis and further studies of relationships with bone mineral density as an outcome are now planned.

Although uncontrolled inflammation, coexisting metabolic syndrome, lifestyle, body habitus and falls risk may all partially explain the results we have presented, a direct effect of urate-lowering agents on bone has also been suggested by other researchers. In recent work, Orriss and colleagues demonstrated that inhibition of xanthine oxidase activity by allopurinol promotes osteoblast differentiation leading to increased bone formation [15] and a beneficial lowering of bone resorption has also been demonstrated in studies in mouse calvarial cultures [14]. Furthermore, since uric acid inhibits 1-alpha hydroxylase protein expression and activity in vivo, it has been suggested that higher uric acid levels are associated with higher parathyroid hormone levels [18], which may be detrimental to bone health and highlights the need to maintain uric acid levels in the normal range.

Our results suggest that gout requiring allopurinol use is a risk factor for osteoporotic fractures in both men and women, but the association is dose dependent with no signal suggesting that high adherence to allopurinol reduces fracture risk, despite observations in vitro that allopurinol is likely to be beneficial to skeletal health. Therefore, the most likely explanation may be that greater severity of gout, with consequent higher and more rigorous use of allopurinol is more strongly associated with increased risk of fracture than milder disease. The observation of a more pronounced impact on fracture risk in hospital-treated patients is suggestive of the same thing. To test the importance of lifestyle factors and medication use, a randomised controlled trial would probably be required to remove the possibility of residual confounding.

The previous literature regarding relationships between uric acid and fracture risk has shown conflicting results. While fracture rates were lower in participants with higher uric acid levels in MrOS [12], the opposite was observed in a study by Mehta et al. [13]. In MrOS, the relative hazard of hip and non-spine fracture was assessed in 1680 men 65 years of age or older in a model adjusted for age, race, body mass index, vitamin D, PTH, walking speed, PASE score, frailty and total hip bone density. In this cohort, hip bone mineral density measures were highest in those with the highest serum urate results; while non-spine fractures were less common at higher serum urate levels, no significant difference was observed in the rate of hip fractures. Given the efficacy of allopurinol as a urate-lowering agent, one might speculate that these results are consistent with an association of lowering urate with higher fracture rates. By contrast, Mehta et al. report higher hip fracture rates among men with the highest urate levels, i.e. a level above 7 mg/dL [13]. These findings mirror the stronger relationships we observed in men compared with women in our own study, and may reflect potential confounding by comorbidity or a thresholding effect. It is possible that a U-shaped relationship exists, with low or high urate levels both associated with adverse outcomes, through differing mechanisms. A recent study of heel ultrasound bone measures in men [19] found a positive association with serum urate levels—but omitted men with a diagnosis of gout or drug therapy that included urate-lowering agents from the study, supporting our hypothesis that within the normal range of serum urate a positive association with bone density may exist, but at higher levels, and in the context of uncontrolled inflammatory arthritis of lower limb joints, fracture risk is elevated.

We found stronger relationships in men than women despite the much higher incidence rates of fractures in the female study subjects. Other investigators have investigated the relationship between uric acid levels and bone health in women as well as men [20]; a recent study reported that, after adjusting for multiple confounders, serum uric acid levels were positively associated with bone density at all sites in women. Recent work has also reported a longitudinal relationship between serum urate and bone health; it has been suggested that serum uric acid may be protective against the development of incident fractures in Korean men [21]. In their discussion, however, the authors of this research concluded that it may be higher uric acid levels within the physiological range that are beneficial; as discussed earlier, our own findings suggest that very high urate levels, associated with an acute, intense inflammatory arthritis and propensity to fall, may not be.

In conclusion, we report an association of allopurinol use with higher fracture rates that was particularly pronounced among men and in patients who also had a hospital diagnosis of gout, suggesting that severe gout itself rather than allopurinol is the reason for this increased risk. We saw increased fracture rates in women receiving the highest allopurinol dosages. Thus, more severe disease—as evidenced by treatment in hospital clinics rather than in GP practice or higher levels of medication use—was associated with high risk of fractures. Our results add to the available evidence highlighting a possible link between allopurinol use and fracture risk; further work is now indicated.

References

Roddy E, Zhang W, Doherty M (2007) Is gout associated with reduced quality of life? A case–control study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 46:1441–1444

Singh JA, Strand V (2008) Gout is associated with more comorbidities, poorer health-related quality of life and higher healthcare utilisation in US veterans. Ann Rheum Dis 67:1310–1316

Lee SJ, Hirsch JD, Terkeltaub R et al (2009) Perceptions of disease and health-related quality of life among patients with gout. Rheumatology (Oxford) 48:582–586

Yoo HG, Lee SI, Chae HJ, Park SJ, Lee YC, Yoo WH (2011) Prevalence of insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in patients with gouty arthritis. Rheumatol Int 31:485–491

Inokuchi T, Tsutsumi Z, Takahashi S, Ka T, Moriwaki Y, Yamamoto T (2010) Increased frequency of metabolic syndrome and its individual metabolic abnormalities in Japanese patients with primary gout. J Clin Rheumatol 16:109–112

Dimitri P, Bishop N, Walsh JS, Eastell R (2012) Obesity is a risk factor for fracture in children but is protective against fracture in adults: a paradox. Bone 50:457–466

Compston E, Netelenbos E, Lindsay R et al (2011) European Congress on Osteoporosis & Osteoarthritis (ECCEO11-IOF). Osteoporos Int 22:97–117

Xu S, Wang Y, Lu J, Xu J (2012) Osteoprotegerin and RANKL in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis-induced osteoporosis. Rheumatol Int 32:3397–3403

Carter S, Lories RJ (2011) Osteoporosis: a paradox in ankylosing spondylitis. Curr Osteoporos Rep 9:112–115

Singh JA, Reddy SG, Kundukulam J (2011) Risk factors for gout and prevention: a systematic review of the literature. Curr Opin Rheumatol 23:192–202

Wang M, Jiang X, Wu W, Zhang D (2013) A meta-analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of gout. Clin Rheumatol 32:1641–1648

Lane NE, Parimi N, Lui LY et al (2014) Association of serum uric acid and incident nonspine fractures in elderly men: the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) study. J Bone Miner Res 29:1701–1707

Mehta T, Bůžková P, Sarnak MJ, Chonchol M, Cauley JA, Wallace E, Fink HA, Robbins J, Jalal D (2015) Serum urate levels and the risk of hip fractures: data from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Metabolism 64:438–446

Kanczler JM, Millar TM, Bodamyali T, Blake DR, Stevens CR (2003) Xanthine oxidase mediates cytokine-induced, but not hormone-induced bone resorption. Free Radic Res 37:179–187

Orriss IR, Arnett TR, George J, Witham M (2014). Treatment with allopurinol and oxypurinol promotes osteoblast differentiation and increases bone formation. Bone Abstracts 3 PP120. doi:10.1530/boneabs.3.PP120

Kildemoes HW, Sorensen HT, Hallas J (2011) The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health Suppl 39:38–41

Andersen TF, Madsen M, Jorgensen J, Mellemkjoer L, Olsen JH (1999) The Danish National Hospital Register. A valuable source of data for modern health sciences. Dan Med Bull 46:263–268

Chen W, Roncal-Jimenez C, Lanaspa M et al (2014) Uric acid suppresses 1 alpha hydroxylase in vitro and in vivo. Metabolism 63:150–160

Hernández JL, Nan D, Martínez J, Pariente E, Sierra I, González-Macías J, Olmos JM (2015) Serum uric acid is associated with quantitative ultrasound parameters in men: data from the Camargo cohort. Osteoporos Int 26:1989–1995

Ahn SH, Lee SH, Kim BJ et al (2013) Higher serum uric acid is associated with higher bone mass, lower bone turnover, and lower prevalence of vertebral fracture in healthy postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 24:2961–2970

Kim BJ, Baek S, Ahn SH et al (2014) Higher serum uric acid as a protective factor against incident osteoporotic fractures in Korean men: a longitudinal study using the National Claim Registry. Osteoporos Int 25:1837–1844

Conflict of interest

Elaine Dennison, Katrine Hass Rubin, Peter Schwarz, Nicholas Harvey, Karen Walker Bone, Cyrus Cooper and Bo Abrahamsen declare that they have no conflict of interest to declare in relation to this manuscript. ED has received speaker fees from Lilly; NH has received consultancy, lecture fees and honoraria from Alliance for Better Bone Health, AMGEN, MSD, Eli Lilly, Servier, Shire, Consilient Healthcare and Internis Pharma. CC has received consultancy fees/honoraria from Servier, Eli Lilly, Merck, Amgen, Novartis and Medtronic. BA has received consultancy fees/honoraria from Nycomed, Takeda, Merck, Amgen, Novartis/ Eli Lilly.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dennison, E.M., Rubin, K.H., Schwarz, P. et al. Is allopurinol use associated with an excess risk of osteoporotic fracture? A National Prescription Registry study. Arch Osteoporos 10, 36 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-015-0241-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11657-015-0241-4