Abstract

The purpose of this study is to develop and test a model in which several aspects of the service encounter including service staff, servicescape, customer similarity, and customer interaction are taken into account simultaneously as antecedents of relationship quality and generation of brand equity. Testing the hypotheses involved two service settings, banks and department stores. The findings demonstrate that serviced staff and customer interaction have significant direct effects on brand equity. Surprisingly, four variables of service encounter have significant indirect effects through relationship quality on brand equity. Based on these findings, the implications for managers and future research are identified.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Strong and positive corporate brand equity is seen as a valuable asset. It is an important asset because such equity involves the service relationship, and the importance of developing and maintaining a long-term relationship with customers is generally accepted in the service industry. Firms operating in this industry must face the increasing challenges of the complexity of customer behavior. Likewise, customers face a myriad of growing choices when considering purchasing options. Unlike buying, say a bar of soap, where the product can be held and immediately compared to other soap in the market place, the intangible nature and volatility of service markets create ambiguity in customers’ perceptions of core service offerings. Given these complexities, it would seem to make sense for service providers to understand as best as they can the factors that affect relationships with customers if they hope to build and maintain long-term relationships.

Brands play a key role in marketing strategy and are increasingly being seen as used by consumers as sources of differentiation. In traditional consumer markets, the marketing emphasis is usually on the performance characteristics of the product. In this context, a brand tends to be associated with a product. But, in a service context, there has been a refocus on the idea of service corporate brands (Mottram 1998). In the service industry, the company itself, rather than a specific product, is often perceived as the brand (Lin and Kao 2004; Netemeyer et al. 2004). A service provider with a good brand reputation will improve the trust of those who consume its service offerings (Berry 2000). The concerned service marketer, then, would very likely find more success in relationship building by developing a positive brand image.

The idea of brand equity is also different between traditional and service markets. In a traditional market, when a consumer buys that bar of soap, brand equity, as perceived by customer, is derived from the overall utility created by the totality of brand association (Agarwal and Rao 1996; Swait et al. 1993). In services, the importance and involvement of the customers increases dramatically because a service as a process provides a much less standardized base for branding. Furthermore, the customer’s participation in the process is seen as a part of the basis for brand development. In a traditional market, brand equity is evident when a transaction occurs. In the service sector, brand equity may not have been “achieved” in the instance when the customer buys a product.

To the customer accepting a service offering, a brand provides a promise or a bond with the providers, thus establishing a relationship. Brand equity based on a relationship dimension refers to the effect that brand knowledge has on the customer’s response to the marketing of that brand. Equity occurs when the customer interacts with the service provider and holds a strong brand loyalty in his/her memory through trust and satisfaction (Grönroos 2000).

In the academic landscape, Schultz and Barnes (1999) suggest that the theory of relationship brand has been one of the integral conceptual issues in service marketing research. As a practical matter, numerous scholars have argued that the development of favorable relationship-oriented brand equity is an important aspect of the service provider’s strategy to maintain long-term relationships with customers (Grace and O’Cass 2005; De Chernatony and Dall’Olmo Riley 1998). For this reason, we define a relationship-based brand equity is that the identification of key drivers that influence the brand equity of the services through relationship quality and a better understanding of the causal relationship between these drivers and brand equity. Driven by the notion of relationship brand equity as an important concept, this study seeks to further develop relationship brand equity theory by integrating the research streams of service encounter and relationship quality into a comprehensive model.

To sum up, theories using the aforementioned constructs have been developed in order to help identify service success or failure in service settings. But, the theoretical and empirical knowledge of the relationship between service encounters (e.g., service staff) and brand equity has remained relatively scarce. Specifically, we need to consider the notion of relationship quality. From the customer’s viewpoint, relationship quality refers to a customer’s perception of how well the service process fulfills the expectations and desires the customer has concerning the whole relationship over time. It is not clear how service encounter variables influence brand equity via trust and satisfaction. Therefore, this article proposes and tests a model in which relationship quality, defined in terms of satisfaction and trust, is conceived of as mediating the relationships between service encounters, divided into three factors—service staff, servicescape and customer interaction, and brand equity.

2 Theoretical background and hypotheses

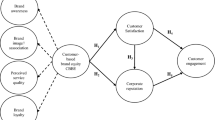

Berry (2000) has argued that a strong service brand represents a satisfactory service process. Because of this, a clearer understanding of the service process is essential in the attempt to understand the factors affecting brand equity. Services are inherently relational. A service encounter is a process. In this process the service provider (e.g., service staff) is present other than technological-based encounter (e.g., ATM and internet), interacting with the customer as well as providing the servicescape. If a customer perceived the process is attractiveness, care, and friendliness in his/her contacts with a given provider, then a positive relationship may develop. Relationship quality can be described as the long-term positive and/or negative formation in ongoing customer relationships (Kim and Cha 2002; Gummesson et al. 1995). From the customers’ viewpoint, relationship quality is continuously developing and is based on their perceptions of the relationship over time. Where the service encounter concept focuses on the emergence of the relationships, the aspect of relationship quality focuses on the maintenance of relationships. Both constructs are posited based on the view of the centrality of relationships in the realization of brand equity. Figure 1 depicts the relationship-based brand equity model. More specifically, the figure shows the effects of service encounter on the brand equity and the mediating effects of relationship quality which we discuss in the following sections. The following section delineates the importance of relationship quality of establishing the brand equity.

2.1 Service encounter: service staff

The concept of service encounter was first proposed by Solomon et al. in 1985. Since then, some scholars have focused on the interaction between service employees and their customers (e.g., Söderlund and Rosengren 2004). More recently, physical equipment has also received much study (Mattila and Wirtz 2001; Dube and Morin 2001). Service encounter means that the customers interact with staff, with various physical equipments, and with other customers simultaneously involved in the service process. A well-trained service staff, a good servicescape, customer similarity, and also customer interaction have to be considered when one is exploring the agenda of brand equity. Service providers use these four components to establish good relationships. In line with the above conceptualizations, this study has posited that service encounter includes the four dimensions of service staff (Swan et al. 1985), servicescape (Grewal et al. 2006), customer similarity (Doney and Canon 1997; Fox et al. 2004), and customer interactions (Smith 1998; Mangleburg et al. 2004).

Everything that a firm supplies for its customers is first perceived by its own employees. If employees do not know how to implement a service offering or how to use a technology in the service process, the firm cannot expect customers to be satisfied by the service. A service provider can yield an outstanding service process when he has good employees. Service employees need to act professionally by incorporating technical skills with good interpersonal skills. Technical skills encompass all the knowledge required related to process and machines. Good interpersonal skills include skills such as attentive listening, body language, and appropriate facial expressions.

A well-trained employee is much more likely to be respected and trusted by his/her customers, especially in high contact services. Because of the intangible nature of service, special attention has to be paid to making the benefits of a particular service clearly understood. Communicating information about a service can be very difficult. Therefore, it is a good idea for services to try to make the service employee’s approach more concrete and candid. When customers perceive the friendly attitude of a service employee, a dyadic relationship emerges and satisfaction will be raised (Aron et al. 2001). Therefore, a well-trained staff, as perceived by customers, is likely to have a positive influence on relationship quality as well as on brand equity.

In addition to staff skills, the attitude of closeness is necessary for a good service process. Many service providers are seeking to develop “closeness” with their customers for the purpose of curtailing the interpersonal distance in the relationships (Aron and Fraley 1999; Sirdeshmukh et al. 2002). The sense of closeness improves the dyadic perception of equity and satisfaction and further develops a friendly relationship (Medvene et al. 2000; Wong and Sohal 2002). Based on the above, we argue that the ability of service staff to engender this sense of closeness is an important variable to test in the brand equity model.

Many services tend to be high in credence attributes that present challenges for service marketers. This requires them to find ways to reassure customers and reduce the perceived risks. For example, doctors display their degrees, lawyers highlight their expertise, and insurance clients present their health records (Crosby et al. 1990). This is done to create a sense that the provider is willing to share information which customers would hopefully find reassuring. Along this same line of thought, encouraging the customer to share information about him/herself is also an important consideration for providers. This sharing, or disclosure, means the situation where an individual cordially expresses his/her feelings and experiences in consuming the service process (Quatman and Swanson 2002). Disclosure leads to a feeling of acceptance of a partner’s opinions. Mutual disclosure would seem to be an effective method for enabling relationship quality, and subsequently, brand equity to be generated. In order for a relationship to derive these benefits, a service provider must have a staff capable of guiding a relationship so that mutual disclosure occurs. Given the above, we hypothesize that

H1a:

The customers’ perception of a service staff is positively related to relationship quality.

H1b:

The customers’ perception of a service staff is positively related to brand equity.

2.2 Service encounter: servicescape

Servicescape refers to “the appearance of the physical surroundings and other experiential elements encountered by customers at service delivery sites” (Lovelock and Wirtz 2004). Many service providers use the concept of servicescape to enhance their service offerings because physical surroundings help to shape appropriate feelings and increase service quality (Bitner 1992).

Atmosphere is another aspect of the servicescape. Atmosphere is the part of the environment pertaining to the five human senses. These conditions affect customers’ emotional well-being, perception, and attitudes (Sirgy et al. 2000). An ambient environment can clearly communicate its expected positioning and is particularly important in setting service expectations. Similarly, customers frequently evaluate satisfaction of service based on the service environment. Customers infer higher service quality if the goods are displayed or the services are supplied in an ambient environment conveying a prestigious and professional image (Sherman et al. 1997).

The challenge in providing for a good store atmosphere is to use music, scent, color, and signs to attract customers to the process of service delivery. Customers easily feel uncomfortable in an unfriendly environment and even experience anger and dissatisfaction as a result. However, a clever design of a store atmosphere can elicit desired behavioral responses from customers (Richard and Eric 2000). Numerous studies have found that friendly service settings increase satisfaction levels, which can then lead customers to perceive higher quality, trust service providers (Hoffman et al. 2002), and generate brand association in customers’ memory (Yoo et al. 2000). Therefore,

H2a:

The servicescape is positively related to relationship quality.

H2b:

The servicescape is positively related to brand equity.

2.3 Service encounter: customer similarity and interaction

One of the most important agendas for a service provider is to develop the ability to predict how consumers will act. Success in this endeavor is far from easy because consumers in nature differ substantially in how they choose to act. Consumer analysts have generally used consumer characteristics, such as age, gender, education, and psychographics, to address the difficulty of measuring behavior. It is relatively easy to measure these characteristics, which can then be used to define customers with similar behaviors. While other variables may be involved, consumers in general, though, do associate specific brands of products and services with their interests and satisfaction. Therefore, customer similarity is an important concept in developing a relationship quality because it provides some traction that can allow service providers to predict how customers will act (Martin and Pranter 1989).

According to social identity theory (Heider 1958; Stryker 1968; Turner 1978), people need to distinguish themselves from others in social contexts. While this may be true, consumers are motivated to maintain a consistent sense of self both over time and across situations (Bhattacharya and Sen 2003). When they are grouped by the same income, social position, or lifestyle as those of others, and when they are in relationships with a provider and interact with it on a frequent, intimate basis, this leads to the enhancement in the level of trust in the provider. Such trust emerges based on similarity–attraction theory (Nass and Lee 2000).

The similarity–attraction stream of research is predicated on the notion that similarity in attributes, particularly demographic variables, increases interpersonal attraction and liking [sic] (Byrne et al. 1966). Customers with similar backgrounds may find that they have more in common with each other than with others from different backgrounds, making it more comfortable for them when consuming a product. Such cohesion allows the provider to dovetail service suitable to that group of customers (Kim and Cha 2002).

H3a:

The similarity of customers is positively related to relationship quality.

H3b:

The similarity of customers is positively related to brand equity.

The interaction of customers with others also seems to be involved in the service process. When a customer perceives the quality of the service encounter, whether at the time of consumption or in advance, he/she may pass on that perception to other potential or actual customers. Customers’ interactions can have a substantial immediate effect as well as a long-term impact (Ostrom and Iacobucci 1998). Customer interaction refers to the exchanges of consumption experiences, product knowledge, and market information that can be directly communicated by customers who can be segmented by a similar behavior (Harris 1993; Martin and Pranter 1989). This accelerates the developing of friendship and social bonds among groups of customers, a situation that serves to illustrate the view of a customer-interactive system (Adelman et al. 1994; Martin and Pranter 1989). In an interactive system, any of the customers can change others or be changed by others at any time. Therefore, the interactive process is an important factor to influence the level of satisfaction (Solomon et al. 1985). Hence,

H3c:

The interactions of customers are positively related to relationship quality.

H3d:

The interactions of customers are positively related to brand equity.

2.4 Relationship quality: trust and satisfaction

The literature on relationship quality reports extensively on trust and satisfaction (Kim and Cha 2002). Trust has been conceptualized as the confidence that relationship partners have in the reliability and integrity of each other (Morgan and Hunt 1994). Trust is increased and uncertainty is reduced in those interactions where more information is provided. Trust also can serve as a mechanism for coping with opportunistic behavior. In both of these cases, trust can contribute to the improvement of dyadic relationships. As a result, customer turnover may be reduced, brand loyalty may be improved, and brand association may be fixed in the customer’s mind (Aaker 1996).

Cardozo (1965) initially applied the idea of satisfaction to the marketing field. Since that time, the notion of satisfaction has become one of the paradigms of marketing theory. Olsen and Johnson (2003) see satisfaction as a cumulative evaluation of a customers’ consumption experience. This study posits that relationship quality includes the two dimensions of trust and satisfaction (Crosby et al. 1990). Trust and satisfaction are factors that customers can refer to when they compare their experiences with prior expectations in the process of evaluating the service in its totality, e.g., the service encounter and the relationship quality. The more the trust and satisfaction with the service process, the stronger the association is between information nodes and brand nodes in the memory. The brand sale and cross-sale will be recommended to other consumers (Bloemer and Odekerken-Schroder 2002). Thus, brand equity should be enhanced.

This study has posited that brand equity consists of brand loyalty and brand association. Basically, it seems reasonable to accept that there is a positive relationship between satisfaction and loyalty. Furthermore, a firm almost always needs to go beyond what normally can be described as good service to create loyalty. Some early works argued that customers’ loyalty is related to the maintenance of a long-term relationship with a brand or an organization (Prus and Brandt 1995). Later work (Adams 2006) attempts to develop a framework to provide a quantitative method for measuring the steps communicators need to accomplish to achieve customers’ brand loyalty. Some works suggest firms implement the integrated marketing communication (IMC) strategy to build brand equity because IMC makes the value attach to brand equity based on the relationships between customers and providers (Anantachart 2004; Kim 2001). Additionally, a customers’ satisfaction with a specific brand often results in their repurchasing the same brand. Thus, when a customer is satisfied by the experience of service, a positive image of the service brand will be remained in his/her mind (Keller 1993).

Brand association means that existing awareness, positive affect, and purchase intention are associated with a well-known brand by extending the brand to new products (Martin and Stewart 2001). Although the linkage of relationship quality to brand equity has rarely received direct attention from researchers, however, Ranaweera and Prabhu (2003) use brand as an important and desirable consequence of customer satisfaction. In this way we can say that brand equity reflects the quality of the service encounter. Having explored the concepts of the service encounter, relationship quality, and brand equity, we show the theoretical model in Fig. 1 and have developed the hypotheses with regard to these constructs. Accordingly, we also posit:

H4:

Relationship quality positively influences brand equity.

3 Method

3.1 Selection of services

Two services (department stores and banks) were chosen to test the proposed model. Some criteria suggested by Bowen (1990) formed the basis for selecting two services under investigation. For example, the selection considered whether the service was directed at a person or not and the level of contact between the provider and the customer. Department stores were chosen because, according to the published data from the Official Statistical Bureau of Economics Department, department stores have had the highest revenue share (about 26%) among all retailing industries from 1999 to 2003. Department stores began testing relationship marketing programs in the late 1900s. Traditionally, department stores attracted customers by offering a pleasing ambience, wide variety of merchandise, and an attentive service. It is a discretionary and enjoyable purchase by directly contacting a person. If the customer faces the contact is unfriendly, he/she is very easy to switch. Interactions in this market typically belong to that of a generic service encounter.

Retail banking began to focus on establishing long-term relationships with customers because their market share had declined in the face of aggressive competition from other financial institutions. Customers’ satisfaction with the banking industry depends on the ability of bank employees to perform repeated tasks (e.g., deposit product) and interact with customers (e.g., loan product). It is an important exchange because it involves a customer’s loan records. The customers are attracted by the providers with credence attitude and good financial skill. It probably leads to difficulty in switching. Thus, interactions in this market belong to high-contact services. It was felt that these two services, where the relationships between providers and customers are common to the service industry in general, were sufficient to allow for generalizing the results beyond a single service setting.

3.2 Data collection procedure

To test the aforementioned hypotheses, we gathered the data using mail surveys. We sent out 1,025 questionnaires (department store: 525; bank: 500) and received 206 responses within 1 month (department store: 124; bank: 82). This represented a response rate of 20.09%. We mailed a second questionnaire to 819 non-respondents. We received 143 more responses from the second questionnaire (department store: 86; bank: 57). Totally, the response rates were department store 40% (N = 210) and bank 27.8% (N = 139). The overall response rate was 34.04% (N = 349). After the elimination of 29 questionnaires, which had an excessive amount of missing data (above 3% of data points), the final sample consisted of 320 respondents. Furthermore, we performed a difference test between respondents and non-respondents. No significant t-test differences (p = 0.01) were found between early and late respondents on any item of the questionnaires (Armstrong and Overton 1977).

The demographic profile of the sample was compared with the population characteristics where the study was undertaken. No significant differences were found between age (under 20, 5.3%; 20–30, 61.9%; 31–40, 22.8%; above 40, 10%) and sex (43.4% of respondents male and 56.6% female). However, significant differences were found on education (sample under-represented in less than high school, over-represented in above college education). The length of relationship with the bank or department store ranged from 1 to 47 years and averaged 13.4 years (SD = 8.9 years).

3.3 Measurement

To measure service staff, we used nine items, including three items of technical skill based on a salesperson expertise index (Crosby et al. 1990) and three items of closeness based on an interaction orientation of salesperson scale (Williams and Spiro 1985). The other three items of interaction disclosure were drawn from the salesperson customer orientation scale (Saxe and Weitz 1982). With regard to servicescape, the measure for physical equipment (four items) and atmosphere (six items) was based on the customer switching behavior scale developed by Bitner (1992) and Keaveney (1995). Customer variables were measured with two subscales. Customer similarity and customer interaction each were measured by three items based on the salesperson expertise index and interaction oriented customer scale, respectively.

For the measurement of relationship quality, we used six items measuring trust based on the trust in the salesperson index (Crosby et al. 1990) and five items for satisfaction, which were adapted from Oliver and Desarbo (1988) and Bitner (1990). Finally, we measured service brand equity, encompassing service brand loyalty (three items) and service brand association (three items), which were based on a scale developed and validated by Aaker (1996). We used five-point scales anchored by “strongly disagree” and “strongly agree.” Examples of measures are reported in Appendix. To purify further the multidimensional measure of service encounter, relationship quality, and brand equity, a confirmatory factor analysis of the 52 items and 6 sub-constructs was performed and reported in Appendix. All loadings are significant. Goodness-of-fit statistics are χ2 = 88.49 (p = 0.00), df = 53, RMSEA = 0.058, AGFI = 0.81, and GFI = 0.90. The fit statistics are as expected.

3.4 Validation

Convergent validity can be demonstrated when items factor loading are greater than 0.7 (Fornell and Larcker 1981). The four dimensions of service encounters and two subscales of relationship quality and brand equity were measured with multi-dimensional measures. This means that we used subscale scores rather than individual items as indicators of these latent variables. In line with this, the problem of fitting models with 11 indicators (about 52 items) could be dealt with through structural equation modeling. With the constraint of only a moderate sample size and a parsimonious rule, we also tested the validity of four-dimensional nature of service encounter through a second-order factor analysis. All four path coefficients between the higher-order constructs and the four dimensions are significant at α = 0.05. The results are χ2 = 32.198, df = 24, CFI = 0.987, and RMSEA = 0.062. Thus, we deemed our second-order scales of service encounter adequate for the purpose of this study. This means that the constructs were represented by a composite formed by the average of scores of all items in a subscale. Summary descriptive statistics and the correlation matrix of constructs are shown in Table 1. The nomological validity of constructs involved in the model can be observed in the correlations between constructs. More specifically, the directions of all relationships hypothesized in the model were supported. Strong evidence of nomological validity was demonstrated.

4 Results

To test these hypotheses, we used AMOS 5.0 (Arbuckle 2003) to obtain maximum likelihood estimates of the standardized path coefficients. It can be concluded that the fit of this model was good and accepted. The results in Table 2 show that all goodness-of-fit measures well exceed the recommended cutoff values. The test of our hypotheses and respective findings carry important implications, all of which are discussed below.

4.1 Variable effects

H1a is supported by a significant positive relationship between service staff and relationship quality (β = 0.344, t-value = 6.723, p ≦ 0.01). Relationships in the service industry are a complicated phenomenon. As Morgan and Hunt (1994) also suggest, trust is a central construct in relationship marketing. In the retail context, satisfied customers and friendly employees are associated with trusting relationships (Wong and Sohal 2002). To achieve relationship-based brand equity, a service-oriented employee is thought of as the most important resource (H1b). From a managerial viewpoint, high relationship quality is not the final purpose. The final purpose is customers’ brand loyalty or association, which the service provider can enhance by hiring or training an excellent service staff.

Surprisingly, the proposed relationship between servicescapes and relationship quality (H2a) was not supported. The relationship was positive as predicted but was not statistically significant (β = 0.244, t = 1.161, p > 0.1). The following reasons may explain this situation. First, does providing an entertaining store atmosphere lead customers to perceive satisfaction and spend more time and money during each visit? The major answer depends on the different customers’ needs such as task completion and recreation. The atmosphere developed will likely not appeal to all customers. Therefore, a store atmosphere difficultly establishes the long-term relationship. Second, the servicescapes are too frequently developed according to company’s internal resources; the objective of high servicescapes quality is to promote the brand rather than achieve long-term relationship. The external effect of, for example, a technical system or store atmosphere is seldom taken into account to satisfy target customer’s need. Consequently, the servicescapes may not nurture the customers’ trust or satisfactory in the service process. Hence, in order to drive hedonic shopping, increase repeat purchasing, and even generate brand loyalty, a customer-oriented store’s atmosphere should be considered as the most important means available to service firms when developing the servicescapes strategy.

The results signify that we can accept H3a (β = 0.382, t = 5.615, p < 0.05). Customer similarity should be accounted for in the strategic decisions providers make as they seek to develop service brand positioning and trusting relationships. If a firm is known for service excellence, customers will deliver this information to other customers. Positive customer interaction and information sharing will result in satisfaction. Thus, the greater the customer homogeneity, which leads to more interaction, the higher the trust and satisfaction in the relationships will be between customers and service firms.

Strongly significant positive relationships were found between relationship quality and brand equity (β = 0.446, t = 7.396, p < 0.01). Hence, we accept H4. In this study, relationship quality was measured as a composite index of trust and satisfaction. High relationship quality means that the customer can rely on the firm’s integrity and has confidence in the firm’s future performance. This should not be surprising as a consumer’s perception of satisfaction and trust in a firm clearly contribute to string brand association and behavioral brand loyalty in the future. Brand equity represented the added value that accrues to a service or an offering of a marketing effort (Moore et al. 2003). In the context of relationships; the equity is the customer’s perception of how valuable a given service process is to him through satisfaction or trust. If the perceived satisfaction declines, the customer will be more interested in other brands. On the other hand, if the trust relationship has been nurtured, the likelihood that the customer will stay loyal can be expected to increase. In line with this rationale, it is meaningless to try to develop a brand without taking into account the notion of the relationships. In the traditional goods market, the marketer can implement activities which create a brand. However, in the services, the brand equity is created based on long-term relationships.

4.2 The mediating effect of relationship quality

The direct, indirect, and total standardized effects among the constructs in the final brand equity model are shown in Table 3. Meanwhile, in the diagram of the model, a single arrowhead path, from one latent variable to another, means that the first variable was hypothesized to have a structural direct effect on the second variable. Although the direct effect of servicescapes (H2b) was not a positive significant on relationship quality as proposed in the proposal model, the respective direct effects of service staff (H1a), customer similarity (H3a), and customer interaction (H3c) on relationship quality were statistically significant.

Indirect or mediating effects “involve one or more intervening variables that transmit some of the causal effect of prior variables onto subsequent variables” (Kline 1998). Service staff (β = 0.124, t = 6.012, p > 0.01), customer interaction (β = 0.102, t = 6.172, p < 0.01), and relationship quality (β = 0.446, t = 7.396, p < 0.01) have a positive significant effect on brand equity. However, servicescape (β = 0.019, t = 1.887, p < 0.05) has a non-significant positive effect and customer similarity (β = −0.028, t = −1.298, p > 0.1) has a non-significant negative effect on brand equity, respectively. Two important findings need to be mentioned. First, relationship quality has an obviously stronger direct effect on brand equity than those of the other latent constructs. Second, it is interesting to observe that service staff (β = 0.153, p < 0.01), servicescape (β = 0.109, p < 0.05), and customer similarity (β = 0.170, p < 0.01) have a stronger indirect effect on brand equity via relationship quality than they do directly. Therefore, as predicted, the results suggest that relationship quality does act as a critical mediator.

Further results lend additional support to the role of relationship quality as a mediator. The highest total effect on brand equity is derived from relationship quality (0.466); the second highest is from service staff (0.277), where the direct effect was 0.124 and the indirect effect 0.153 through relationship quality. This finding should be anticipated on the basis of the nature of interpersonal interactions in relationship exchanges. On the other hand, this model did account for all the effects attributed to the use of relationship quality on brand equity. The direct impact of servicescapes and customer similarity on brand equity was non-significant, while at the same time, their indirect effects were larger than their direct effects. Although the direct effect of service staff was significant, interestingly, its direct effect was smaller than its indirect effect via relationship quality. Consequently, we confirm that relationship quality serves as a full mediator. More specifically, for the service provider intending to create brand equity, a trusting relationship and satisfactory service are prerequisite conditions.

5 Discussion, limitations, and future research

The results of our investigation provide a number of unique contributions for theory and for managerial practice. Based on previous research, this study examined the direct impact of interpersonal encounters, physical service surroundings, customer similarity, and customer interaction on relationship quality and brand equity, respectively. However, previous research rarely simultaneously explored the issues of relationship quality and brand equity. Deepening a trusting relationship within a service process will, by its nature, tend to increase brand loyalty and brand association (Keating et al. 2003). Our findings suggest that relationship quality plays a critical mediating role in creating brand equity in services.

Thus, this model adds to the paradigm of research on service sector relationships. Past research on brand equity has emphasized the investigation of tangible products. The present study has extended the knowledge of the impact of service encounter constructs on brand loyalty and brand association by showing that relationship quality is an important mediating variable in service settings. The decomposition of structural effects into direct and indirect effects has been scarcely analyzed in the service marketing literature. The present article provides more robust and thorough research about how constructs interrelate.

One of the surprising findings was that, contrary to our expectation, customer similarity did not have a significant direct effect on brand equity. In fact, the former had a negative direct effect on the latter. The negative relationship between customer similarity and brand equity seems somewhat curious. This situation may be explained by Hoffman and Bateson (1997). They posited that customers’ unsatisfactory experience destroyed brand equity and that this dissatisfaction was rapidly spread by homogeneous customers. Anderson and Zemke (1991) named them as “customers from hell.” However, this negative effect can be staunched through building trust and satisfaction in the dyadic relationship, which should then serve to foster a change in attitude toward brand loyalty.

To sum up, these findings also have managerial implication. Managers clearly need to pay attention to brand equity issues in general, something they neglect to do. For instance, they clearly need to focus most of their attention on the service staff, servicescapes, customer similarity, and customer interaction. To develop long-term brand equity, managers should focus on customers satisfactory and trust, their strategies for enhancing brand loyalty and strong brand association through relationship quality are much more likely to be successful.

Future research on the development of relationship-based brand equity might be advanced in several ways. First, a different approach toward relationship quality could broaden our perspective concerning the relevant issues involved in relationships in service settings. The current study focused on a limited number of mediating variables, trust, and satisfaction. Future research should be directed at other variables such as affective commitment, affective conflict, opportunism, or mutual goals.

Second, previous research has suggested additional types of brand loyalty such as brand awareness and brand meaning (Berry 2000). Since the construct as tested in our design has been limited to brand loyalty and brand association, future research could extend the present work of the effect of relationship quality on other sub-constructs of brand equity, including brand uniqueness (Netemeyer et al. 2004), brand image (Kim and Kim 2005), and brand performance (Prasad and Dev 2000).

Third, the survey used to measure this model was implemented at one point in time. Basically, the assumption that relationships are static is somewhat unreasonable. From a practical viewpoint, it may be worthwhile to take into account a dynamic perspective of relationship quality over time in the service market. Fourth, our study may also be limited by the samples we obtained. The sample was predominately made up of higher educational level, and then the data need to be interpreted with care. Finally, generalizing the results of our study should be discretionarily considered. Although the model was tested in two service industries, future research can serve to better clarify how broadly these findings can be applied by exploring samples from service encounters that take place in different service settings.

References

Aaker DA (1996) Measuring brand equity across product and markets. Calif Manag Rev 38(3):102–120

Adams JW (2006) Striking it niche—extending the newspaper brand by capitalizing in new media niche markets: suggested model for achieving consumer brand loyalty. J Website Promot 2(1&2):163–184

Adelman MB, Anuvia A, Goodwin C (1994) Beyond smiling: social support and service quality. In: Rust RT, Oliver RL (eds) Service quality: new directions in theory and practice. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA

Agarwal MK, Rao VR (1996) An empirical comparison of consumer-based measures of brand equity. Mark Lett 7(3):237–247

Anantachart S (2004) Integrated marketing communications and market planning: Their implications to brand equity building. J Promot Manag 11(1):101–125

Anderson K, Zemke R (1991) Customer from hell. Training 26:25–31

Arbuckle J (2003) Amos™ 5.0 update to the Amos user’s guide. Smallwaters Corporation, Chicago

Armstrong JS, Overton ST (1977) Estimating non-response bias in mail surveys. J Mark Res 14:396–402

Aron A, Fraley B (1999) Relationship closeness as including other in the self: cognitive underpinnings and measures. Soc Cogn 17:140–160

Aron A, Fraley B, McLaughlin-Volpe T (2001) Including others in the self: extensions to own and partner’s group memberships. In: Sedikides C, Brewer MB (eds) Individual self, relational self, collective self. Psychology Press, Philadelphia, pp 89–108

Berry L (2000) Cultivating service brand equity. J Acad Mark Sci 28(1):128–137

Bhattacharya CB, Sen S (2003) Consumer-company identification: a framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. J Mark 67(April):76–88

Bitner MJ (1990) Evaluating service encounters: the effects of physical surroundings and employee responses. J Mark Res 54:69–82

Bitner MJ (1992) Servicescapes: the impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. J Mark 56:57–71

Bloemer J, Odekerken-Schroder G (2002) Store satisfaction and store loyalty explained by customer- and store-related factors. J Consum Satisf Dissatisf Complain Behav 15:68–80

Bowen DE (1990) An interdisciplinary study of service: some progress, some prospects. J Bus Res 20:71–79

Byrne D, Clore G, Worchel P (1966) The effect of economic similarity dissimilarity as determinants of attraction. J Pers Soc Psychol 4:220–224

Cardozo RN (1965) An experimental study of customer effort, expectation, and satisfaction. J Mark Res 2:244–249

Crosby LA, Evans KR, Cowles D (1990) Relationship quality in services selling: an interpersonal influence perspective. J Mark 54(3):68–81

De Chernatony L, Dall’Olmo Riley F (1998) Defining a “brand”: beyond the literature with experts’ interpretations. J Mark Manag 14:417–443

Doney PM, Canon JP (1997) An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. J Mark 61:35–51

Dube L, Morin S (2001) Background music pleasure and store evaluation intensity effects and psychological mechanisms. J Bus Res 54:107–113

Fornell C, Larcker D (1981) Evaluating structural equation model with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18:39–50

Fox E, Montogmery A, Ledish L (2004) Consumer shopping and spending across retail formats. J Bus 77:525–561

Grace D, O`Cass A (2005) An examination of the antecedents of repatronage intentions across different retail store formats. J Retail Consum Serv 12:227–243

Grewal D, Baker J, Levy M, Voss G (2006) The effects of wait expectations and store atmosphere evaluations on patronage intentions in service-intensive retail store. J Retail 79(4):259–268

Grönroos C (2000) Service management and marketing. Wiley, West Sussex

Gummesson E, Glynn WJ, Barness JG (1995) Relationship marketing: its role in the service economy, understanding service management. Oak Tree Press, Dublin

Harris RB (1993) Trust in relationship marketing: a foundation for building business. Manag Mag 68(6):14–17

Heider F (1958) The psychology of interpersonal relations. Wiley, New York

Hoffman KD, Bateson JEG (1997) Essentials of services marketing. The Dryden Press, Orlando

Hoffman KD, Bateson JEG, Turley LW (2002) Atmospherics, service encounters and consumer decision making: an integrative perspective. J Mark Theory Pract 10(3):33–47

Keating B, Rugimbana R, Quazi A (2003) Differentiating between service quality and relationship quality in cyberspace. Manag Serv Qual 13(3):217–232

Keaveney SM (1995) Customer switching behavior in service industries: an exploratory study. J Mark 59:71–82

Keller LK (1993) Conceptualizing, measuring and managing customer-based brand equity. J Mark 57(1):1–22

Kim Y (2001) The impact of brand equity and the company’s reputation on revenues: testing an IMC evaluation model. J Promot Manag 6(1/2):89–111

Kim WG, Cha Y (2002) Antecedents and consequences of relationship quality in hotel industry. Hosp Manag 21:321–338

Kim H, Kim WG (2005) The relationship between brand equity and firms’ performance in luxury hotels and chain restaurants. Tour Manag 26:549–560

Kline RB (1998) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. The Guilford Press, New York

Lin CH, Kao DL (2004) The Impacts of country-of-origin on brand equity. J Am Acad Bus 5(1/2):37–40

Lovelock C, Wirtz H (2004) Services marketing—peoples, technology, strategy, 5th edn. Prentice Hall, NJ, pp 285–286

Mangleburg T, Doney P, Bristol T (2004) Shopping with friends and teen’ susceptibility to peer influence. J Retail 80(2):101–123

Martin CL, Pranter AP (1989) Compatibility management customer-to-customer relationships in service environments. J Serv Mark 3:6–15

Martin MI, Stewart DW (2001) The differential impact of goal congruency on attitudes, intentions, and the transfer of brand equity. J Mark Res 38:471–484

Mattila AS, Wirtz J (2001) Congruency of scent and music as a driver of in-store evaluations and behavior. J Retail 77:237–289

Medvene LJ, Teal CR, Slavich S (2000) Including the other in self: implications for judgments of equity and satisfaction in close relationships. J Soc Clin Psychol 19:396–419

Morgan RM, Hunt SD (1994) The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. J Mark 58:20–38

Moore SE, Wilkie WL, Lutz RJ (2003) Passing the torch: intergenerational influences as a source of brand equity. J Mark 66:17–37

Mottram S (1998) Branding the corporation. In: Hart S, Murphy J (eds) Brands: the new wealth creators. New York University Press, USA

Nass C, Lee KM (2000) Does computer-generated speech manifest personality? An experimental test of similarity-attraction. Proceedings of ACM CHI 2000, pp 330–335

Netemeyer RG, Krishnan B, Pullig C, Wang G, Yagci M, Dean D, Ricks J, Wirth F (2004) Developing and validating measures of facets of customer-based brand equity. J Bus Res 57(2):209–224

Oliver RL, DeSarbo WS (1988) Response determinants in satisfaction judgments. J Consum Res 14:495–507

Olsen LL, Johnson MD (2003) Service equity, satisfaction, and loyalty: form transaction-specific to cumulative evaluations. J Serv Res 5(3):184–195

Ostrom AL, Iacobucci D (1998) The effects of guarantees on consumers’ evaluation of service. J Serv Mark 12(6):362–378

Prasad K, Dev CS (2000) Managing hotel brand equity—a customer-centric framework for assessing performance. Cornell Hotel Restaur Adm Q 41(3):22–31

Prus A, Brandt DR (1995) Understanding your customers. Mark Tools 2(5):10–14

Quatman T, Swanson C (2002) Academic self-disclosure in adolescence. Genet Soc Gen Psychol Monogr 128(1):1–29

Ranaweera C, Prabhu J (2003) The influence of satisfaction, trust and switching barriers on customer retention in a continuous purchasing setting. Int J Serv Ind Manag 14(3/4):374–395

Richard FY, Eric SR (2000) The effects of music in a retail setting on real and perceived shopping times. J Bus Res 49:139–148

Saxe R, Weitz BA (1982) The SOCO scale: a measure of the customer orientation of salespeople. J Mark Res 19:343–351

Schultz DE, Barnes BB (1999) Strategic brand communication campaigns. NTC Business Books, Chicago

Sherman E, Mathur A, Smith RB (1997) Store environment and consumer purchase behavior: mediating role of consumer emotions. Psychol Mark 14(4):361–378

Sirdeshmukh D, Singh J, Sabol B (2002) Consumer trust, value, and loyalty in relational exchanges. J Mark 66:15–37

Sirgy MJ, Grewal D, Mangleburg T (2000) Retail environment, self-congruity, and retail patronage: an integrative model and a research agenda. J Bus Res 49(2):127–138

Smith JB (1998) Buyer-seller relationships: similarity, relationship management, and quality. Psychol Mark 15(1):3–21

Söderlund M, Rosengren S (2004) Dismantling ‘positive affect’ and its effects on customer satisfaction: an empirical examination of customer joy in a service encounter. J Consum Satisf Dissatisf Complain Behav 17:27–41

Solomon MR, Surprenant C, Czepiel JA, Gutman EG (1985) A role theory perspective on dyadic interactions: the service encounter. J Mark 49(1):99–111

Stryker S (1968) Identity salience and role performance: the importance of symbolic interaction theory for family research. J Marriage Fam 30:558–564

Swait J, Erdem T, Louviere J, Dubelaar C (1993) The equalization price—a measure of consumer-perceived brand equity. Int J Res Mark 10(1):23–45

Swan JE, Trawick FI, Suva DW (1985) How industrial salespeople gain customer trust. Ind Market Manag 14(3):203–211

Turner RH (1978) The role and person. Am J Sociol 84:1–23

Williams KC, Spiro RL (1985) Communication style in the salesperson customer dyad. J Mark Res 12:434–442

Wong A, Sohal A (2002) An examination of the relationship between trust, commitment and relationship quality. Int J Retail Distrib Manag 30(1):34–50

Yoo B, Donthu N, Lee S (2000) An examination of selected marketing mix elements and brand equity. J Acad Mark Sci 28(2):195–211

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions that have helped in finalizing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Samples and factor loading of measurement

Constructs | Samples | Items | Factor loading |

|---|---|---|---|

Service staff | |||

Technical skill | The X personnel are knowledgeable enough to deal with all my questions | 3 | 0.81 |

Closeness | The X personnel are polite and friendly | 3 | 0.82 |

Disclosure | The X personnel attempt to establish a relationship with me | 3 | 0.71 |

Servicescape | |||

Physical equipment | X’s physical equipment is one of the best in its industry | 4 | 0.81 |

Atmosphere | I can rely on there being a good atmosphere | 6 | 0.76 |

Customer similarity | My dressing style is similar to other customers | 3 | 0.87 |

Customer interaction | My interaction with other customers is easy | 3 | 0.74 |

Relationship quality | |||

Trust | I can count on the X to be sincere | 6 | 0.71 |

Satisfaction | Overall, I am satisfied with shopping at X | 5 | 0.85 |

Brand equity | |||

Brand loyalty | I am very loyal to X’s name | 3 | 0.86 |

Brand association | I am committed to my sales associate at X’s name | 3 | 0.86 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, CH., Hsu, LC. & Fang, SR. Constructing a relationship-based brand equity model. Serv Bus 3, 275–292 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-008-0062-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-008-0062-2