Abstract

Although studies on environmental conflicts have engaged with the subject of violence, a multidimensional approach has been lacking. Using data from 95 environmental conflicts in Central America, we show how different forms of violence appear and overlap. We focus on direct, structural, cultural, slow, and ecological forms of violence. Results suggest that the common understanding of violence in environmental conflicts as a direct event in time and space is only the tip of the iceberg and that violence can reach not only environmental defenders, but also communities, nature, and the sustainability of their relations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Grassroot organizations and individuals protest and denounce situations of social and environmental damages leading to environmental conflicts (or ecological distribution conflicts) (Martinez-Alier 1995, 2002). In their struggles to save water and land, their livelihoods, their future, and the future of the next generations, many of them are threatened, wounded, killed, criminalized, and forced to leave their communities (Edelman and León 2013; Aguilar-Støen 2015; Mingorría 2017; Rasch 2017).

Global Witness, an international organization working on environmental abuses and human rights since 1993, has highlighted that during 2015, more than three environmental defendersFootnote 1 were assassinated every week around the world (Global Witness 2016). In most cases, culprits escape unpunished (Global Witness 2014, 2016). Concerned with this, and aiming to move beyond their analysis, in this article, we look at how different forms of violence appear and overlap in environmental conflicts; our objective is to propose a wider conception of violence, in which we consider not only its visible forms, but also violence as unseen processes, whose effect reaches beyond humans.

To do so, we use a database of 95 environmental conflictsFootnote 2 from seven Central American countries (Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama) from the Environmental Justice Atlas database (http://www.ejatlas.org). Central America hosts important biological and cultural diversity, and due to its geological formation, it represents a biological corridor between North and South America with only 0.1% of the world’s land mass yet 7% of the world’s biodiversity. The region has a population of 47,667,000 inhabitants (2016), around 80 indigenous and afro-descendant groups and 60 different languages.

Central America is relevant for studies on violence in environmental conflicts. First, Global Witness (2016) already identified the region as one of the most violent around the world for environmental defenders. Second, an analysis of the whole region using data for the seven countries as we do here is still lacking. Third, because it is a socially, politically, and economically heterogeneous region in which diverse characteristics such as a complex history of war and peace play a role in current environmental struggles (Wayland and Kuniholm 2015). Futhermore, the presence of environmental racism is related to the percentage of indigenous population in each country, for instance, while in Guatemala, 60% of the total population is indigenous, and in Costa Rica, the percentage is around 2%. Finally, because this heterogeneity reinforces the idea that just because violence is not visible, it does not mean that a country does not experience violence, thus necessitating a multidimensional violence approach.

The article is divided as follows. Section 2 briefly describes Central America’s socio-economic background. Section 3 presents a theoretical background on violence and environmental conflicts. Section 4 describes the EJAtlas as a tool to analyze environmental conflicts, and the methods used to gather and analyze how violence appear in these conflicts. Based on regional tendencies and local examples, Sect. 5 synthesizes and discusses the main findings in how different forms of violence appear and overlap. In Sect. 6, we insists on the need for a multidimensional violence approach to address the study of environmental conflicts and in which violence is defined as an action or a process that appears in visible and unseen forms against humans, nature, and the sustainability of their relations. Moreover, we show how violence is not always a response against resistance, but that resistance can also be organized in response to a long-term process of violence. In Sect. 7, we lay out our conclusions.

Central American background: common traits and differences

Latin American history is marked by the plunder of raw materials, inequality, power asymmetries, and violence (Acosta 2009; Bebbington and Bury 2013; Machado 2014; Svampa 2013), and Central America is not an exception. The legacy of colonial and neo-colonial relations, the peace and war historical traits, the external and political influence of the USA (Faber 1992), China as a new economic actor in the region (Urcuyo 2014; McKay et al. 2016), and the increase of drug trafficking routes (McSweeney et al. 2014) are some of the current realities that superpose with extractive industries, pollution, environmental conflicts, and violence.

The establishment of the United Fruit Company (UFCo) in 1899 marks the beginning of an era of neo-colonial relations. Through the International Railways of Central America (IRCA), the company controlled commercial routes and productive lands in Guatemala, Costa Rica, Honduras, and Nicaragua. These countries were nicknamed “Banana Republics”Footnote 3—a pejorative concept to describe poor, small, dependent, and politically unstable nations. For decades, the UFCO promoted enclave economies and influenced governmental decisions for its own benefit (Bucheli 2008).

In much more recent times, geopolitical programs and trade agreements continue to threaten communities at a local level (Grandia 2006). For instance, the Central American Electrical Interconnection System (SIEPAC) under “Mesoamerica Project” (2008) for energy exportation has had an effect on the increase of hydroelectric dam projects (Stenzel 2006). In Guatemala, indigenous Maya-Q’eqchi have protested against the Xalalá dam (EJatlas 2016a) claiming for the protection of the sacred hills that it would flood. In Belize, local communities have been concerned about the loss of biodiversity in the Macal River due to the Chalillo dam (EJatlas 2016b). These two cases—recorded in the EJAtlas—are part of SIEPAC. By ignoring the sacredness of the indigenous environment and failing to recognize local demands, governments have supported these projects under the idea of “national interest” and “development” (EJatlas 2016a, b).

Furthermore, since the signature of diplomatic relations with Costa Rica in 2007, China has kept an eye on the region. One of its interests is to have access to both Atlantic and Pacific oceans for commerce route expansion (Urcuyo 2014). Though investments in extractive, energy, and transport industries, China capitals, go to Central America sources, sometimes without considering environmental, labor, and social conditions (McKay et al. 2016). Key examples on the EJAtlas are Sinohydro’s presence which is becoming common in hydroelectric dam conflicts (EJatlas 2014a, 2017a) and the interoceanic Gran Canal in Nicaragua (EJatlas 2014b).

Moreover, the region is also strategic for drug traffickers, since it connects producers (South America) to consumers (North America), and to increase terrestrial routes, the illegal activity has led to “narco-deforestation” (McSweeney et al. 2014). Trafficking has a relation with extractive industries and environmental damage, since in some cases, traffickers incorporate the illegal income into the legal economy through the investment on lands for cattle, timber, and oil-palm plantations (McSweeney et al. 2014).

Despite commonalities across countries, Central America is very heterogeneous. The consequences of its peace and war history and the gaps between relevant social and economic indicators between countries are some examples of this diversity. During the 1960s and 1990s, some countries were marked as the confrontation stage of popular movements, armed struggles, and repressive regimes (Brockett 2005). Civil war in Guatemala (1960–1995), El Salvador (1979–1992), and Nicaragua (1962–1990) which resulted in 255,000 deaths and thousands of people forcibly disappeared are notorious examples. The strongest guerrilla in El Salvador was called “Farabundo Martí” from the name of the leader of an insurrection in 1932 that ended with tens of thousands of peasant victims, while in Guatemala, the memory of the failed land reform against UFCO because of a military coup in 1954 sponsored by the United States was still fresh. In the wars of the 1960s and 1970s, the victims were mostly from rural areas, affecting indigenous and peasant livelihoods (Kay 2001; Azpuru 1999). Some environmental conflicts mapped on the EJatlas date from the civil war. In 1982, to make possible the construction of the Chixoy Dam in Guatemala, the army and paramilitary forces murdered 444 indigenous Mayan people, the majority of them women and children, these facts were later known as the Río Negro massacre (EJatlas 2015a). The Esquipulas Peace Agreement signed in 1987 was followed by a proliferation of extractive industries. In post-war Guatemala, the government opened the country to mining concessions (Wayland and Kuniholm 2015). In this scenario of open violence and war, Costa Rica was an exception; its history of peace and democracy began in 1948 when the government abolished the army. During this later period, Panama had a military government until the US briefly invaded the country in 1989 and Belize was still part of the British Empire until it reached its independence in 1981.

Overall, Central America’s economy is based in the primary sector (export of raw materials) which is consistent with other Latin American countries. However, Panama’s and Costa Rica’s economies are based on the third sector (services economy). Table 1 shows social and economic indicators per country.

Costa Rica and Panama have the highest Human Development Index in the region and Guatemala and Honduras the lowest. Costa Rica and Panama have the smallest percentage of population living the below income poverty line and (again) Guatemala and Honduras the highest. A gap can also be seen regarding poverty: while CR has 1.6% of its pop living below the poverty line, the value reaches 16% in the case of Honduras. The Democracy Index is higher in Costa Rica (7.88) and Panama (7.13) and lower in Nicaragua (4.81). The homicide rate is higher in Honduras (74.6) and lower in Costa Rica (10). This accounts for a very heterogeneous region. Overall, the Northern Triangle (Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador) has been seen as one of the most violent regions in the world with a combination of strong elites, inequality, and weak institutions (Bull 2014; Van Bronkhorst and Demombynes 2010). These indicators may also be considered a reflection of violence. The next section closely examines different theoretical approaches on the phenomenon and concept of violence.

Theoretical background: violence and environmental conflicts

Studies on violence

Why and how violence emerges has been addressed by scholars from different disciplines. For Peace and Conflict studies, there is a “triangle” with three corners from which violence can start (Galtung 1990). The first corner is direct violence, defined as an event in time and space that is brutal and visible, where perpetrators are human beings (a homicide, for example) (Galtung 1969). The second corner is structural violence. It refers to a process that occurs when social structures undermine individual wellbeing, especially towards discriminated groups as a result of social inequalities and institutional failings such as corruption or poverty (Galtung 1969). This form is less visible than the former and there is no one directly to be blamed except for the entire political and economic structure. The last form is cultural violence, and it indicates the use of cultural elements (religion, ideology, language, science, and technology) to legitimize structural and direct forms of violence. The Xalalà and Chalillo dam projects in Guatemala and Belize in the name of “development” and “national interest” are two key examples of this (EJatlas 2016a, b).

As with Galtung, Nixon was also concerned in expanding the concept of what constitutes violence (beyond its direct form). Moreover, like structural violence, his concept of “slow violence” refers to a process. However, it differentiates as it poses questions of “time, movement and change” (Nixon 2011:11). Slow violence refers to a delayed destruction dispersed across time and space that is incremental, accumulative, and exponential (Nixon 2011). This is the case of climate change, deforestation, and ocean acidification. The persistent accumulated toxic effects on human health because of pollution from heavy metals in open cast mining contexts, or because of the use of damaging chemicals such as pesticides and herbicides are also examples. This form of violence can remain unseen until its accumulative impacts become visible; that is why (and contrary to direct violence), it is difficult for the victims to identify it, to protest and resist against it (Nixon 2011). It is similar to the concept of “slow murder” to describe the health effects of heavy urban traffic pollution in Delhi or the effects of spreading endosulfan in cashew plantations in Kerala. “Slow murder” is a concept that the Centre for Sciences and Environment in India has used for many years (Narain 2007). Endosulfan would of course “slowly murder” both humans and other “innocent” biological entities apart from those targeted.

Nixon refers to a delayed destruction and its environmental aftermaths—using deforestation among other examples—but he mostly focuses on the impact of slow violence on poor and supposedly disposable people. Because of that, we find it relevant to bring into the debate the concept of “ecological violence”, a term aiming to make the violence against the biophysical world and its interrelations visible (Watts 2001). Cases of “ecocide”, a word coined to “denounce the environmental destructions and potential damage of the spraying of the Agent Orange in Vietnam” (Zierler 2011) are an example. Moreover, the “non-focused” deaths or “deaths by indirection” (Carson 1962) to describe how the biocides (instead of insecticides) were poisoning not only enemy insects, but other insects and all forms of life.

As Nixon and Galtung pointed out, there is an issue of inequality, as these forms of violence commonly have an unequal distribution of their effects. Poor and disadvantaged people and nature are the most affected. Through the study of environmental conflicts, we link forms of violence, inequality, and resistance. An ecological distribution conflict—interchangeable with environmental conflict (see Scheidel et al. 2017 this feature)—is defined as “collective manifestation of discontent that detonates when people organize themselves, to denounce situations regarding not only unequal distribution of environmental benefits but also unequal distribution of the environmental costs” (Martinez-Alier and O’Connor 1996).

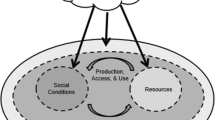

The concept of ‘Violent Environments’ (Peluso and Watts 2001) intersects the study of environmental conflicts, violence, and power relations. Under this notion, ‘environment’ is defined as “an arena of contested entitlements where claims over property, assets, labor, and politics of recognition are played out” (Peluso and Watts 2001: 25). Besides, “violence” is defined as a “phenomenon deeply rooted in local histories and social relations but also connected to transitional processes of material change, political power relations and historical conjuncture” (Peluso and Watts 2001: 29–30). In the following section, we describe the EJAtlas as a tool for the study of environmental conflicts and the different variables used to understand how violence manifests in different environmental conflicts and countries.

Methodology

The EJAtlas is a large-scale database to gather and analyze environmental conflicts around the world (Temper et al. 2015). The unit of analysis is an economic project (a mining project, an oil extraction project, a hydroelectric dam, a tree plantation, among others) which causes visible or potential socio-environmental damage and where impacted people at a local level (but sometimes at a national or regional level) organize themselves to protest against such projects and resist with different mobilization forms. The information gathered on the EJAtlas is the result of collaborative mapping between academics and activists and sometimes also the people most directly affected (Temper et al. 2015).

Methods used to gather information

In selecting the Central American cases, we used a snowball sampling method, asking environmental justice expertsFootnote 4 which cases in the region were the most relevant to enter into the EJAtlas. With this in mind, we made a general list of conflicts based on secondary sources (academic and non-academic articles such as newspapers and websites of environmental defenders’ organizations). Then, we shared the list with experts to validate these cases while asking them to identify other ones. Subsequently, we entered the cases based on secondary sources as well as information previously provided by experts. Data were gathered during the period 2014–2017; in total, it includes 95 environmental conflicts that span nine different types.

Furthermore, the authors of this paper have been engaged for many years in diverse environmental struggles in the region so access to experts was made through personal contacts. This paper’s first author made field trips in 2014 and 2015 to Belize, Guatemala, Panama, and Costa Rica to get feedback and to gather information about less known cases. Often, activists directly involved in the conflict filled in the EJAtlas data sheets based on their own experience and knowledge.Footnote 5

Variables from the EJAtlas used to analyze information

The EJAtlas data sheet has over 100 different variables to compare and analyze (Martinez-Alier et al. 2016). First, to describe conflicts we used “type of conflict”,Footnote 6 “date of beginning of the conflict”, “area of impact (rural, urban, and semi-urban)”, and “mobilizing groups”. To analyze violence, we first chose the variable “intensity of the conflict” which includes latent level (nonvisible organizing), low level (some local organizing), medium level, (street protests and visible mobilization), and high level (widespread mass mobilization, violence in its direct form and arrests, and deaths of demonstrators or activists). We also revised the variables called “impacts” and “outcomes of the conflict”. We placed different variables in Table 2 depending on the definition of violence according to different authors. As it can be perceived, some variables can be placed in more than one form of violence.

Table 2 shows a categorization of variables from the EJAtlas according to the type of violence. However, this relation is not so straight forward; environmental conflicts are complex as is the way violence manifests in them. Who are the main actors (both perpetrators and victims)? How is resistance organized? How do the social structures from different countries shape these forms of violence? Can ecological violence can be both direct and slow? How slow is slow violence? In the next section, we will address these questions by examining both regional trends and local examples from the seven countries.

Results: How does violence manifest in environmental conflicts?

The time span of start dates for mapped conflicts in Central America extends from 1959 to 2015. From the total of cases, 70% occurred in rural areas, 15% in semi-urban, and 10% in urban areas. The rest occurred offshore—such as the oil drilling case in the Blue Hole in Belize (EJatlas 2015b). The most common types are mining extraction (27 cases), water management—mostly hydroelectric dam projects—(23 cases), and biomass and land conflicts—due to monoculture expansion—(17 cases). Infrastructure and built environment, industrial and utilities, and waste management conflicts are less common. Figure 1 situates the conflicts by type and intensity level (high, medium, low, and latent).

Most of the conflicts are “high-level intensity” (around 46%) followed by “medium level” (42%) and low level (10%) and only one case (in Honduras) is “latent intensity”. Minerals’ Extraction and Water Management is the most common and most highly-intense types of conflicts. Guatemala and Honduras are the countries in which—no matter the type of conflict—there are more high-intensity cases. Tourism recreation conflicts are mostly categorized as medium or low-level intensity; however, there is an exception in Honduras, where Garifuna people defend their ancestral lands against a mega-tourist project and a golf course (EJatlas 2014c). In addition, the only high-intensity conflict from fossil fuels and climate justice is located in Guatemala, while the rest are medium level intensity (EJatlas 2015b). Regarding resistance in these conflicts, Fig. 1 also shows how some conflicts overlap offering multifold resistance to more than one project at the same time. The following section explores key examples of different dimensions of violence along Central America. When possible, we identify the actors involved in deploying violence, the victims, and their resistance.

Direct violence

The murder of at least one environmental defender appears in 27% of the cases, violent targeting in 37%, repression in 37%, and criminalization in 38%. Data by country illustrate substantial differences. Guatemala and Honduras seem to be the most directly violent as they make up 79% of the total of cases in which a murder has occurred. Even if the EJAtlas does not specifically count the number of murders by conflict, some asymmetries are relevant to note. The number of murders ranges from one such as in the case of Jeanette Kawas in Honduras (EJatlas 2017b) to at least 444, in the Rio Negro massacre (EJatlas 2015a), while other cases such as the expansion of oil palm in Bajo Aguán, Honduras reported 93 murders (EJatlas 2014d).

Variables on direct violence are not mutually exclusive, and it is common that an assassination is preceded by violent targeting and death threats. One of the most illustrative cases is the Agua Zarca hydroelectric dam in Honduras (EJatlas 2017a), a project affecting and displacing Lenca indigenous people from the sacred river Gualcarque. During a protest in 2013, the community leader Tomás García was shot dead and his son was wounded. Years after, in 2016, Berta Cáceres—who won the world famous Goldman Prize for environmentalism in 2015—was shot to death in her home. Due to her active role against the hydroelectric dam and other extractive projects in Honduras, she previously had received threats against her life (Global Witness 2015).

Another such case is located in El Salvador, where six environmental defenders were killed. The victims (a pregnant woman included) were activists against the El Dorado-Pacific Rim mining project (EJatlas 2017c). Some other female environmental defenders murdered include Alicia Recinos Sorto (El Salvador, 2009), María Enriqueta Matute (Honduras, 2013), Rosalinda Pérez (Guatemala, 2015), Lesbia Yaneth (Honduras, 2016), and Laura Lorena Vásquez (Guatemala, 2017). Similarly, in Panama, during a protest in 2012, violent repression by the police left three environmental defenders dead and more than one hundred wounded. Ngäbe-Buglé indigenous, where protesting against Barro Blanco Hydroelectric Dam Project (EJatlas 2016c) arguing that this project violates the laws that define their territories, water rights, and self-determination.

In general, direct violence is used as a premeditated act to intimidate and demobilize environmental defenders from their resistance. Who the main culprits are often remains unknown and most of these cases remain in impunity (Global Witness 2016); nonetheless, families of the victims and other environmental defenders accuse landowners, foremen, policemen, and goons paid by companies as the main actors.

Traits of structural and cultural violence

In direct violence, governmental institutions fail to ensure justice by passively ignoring and not investigating these murders. However, institutions can also actively play a role in these conflicts through structural and cultural violence. Environmental defenders appeal to State institutions to carry out their actions in the conflict in 50% of the cases; at times, this form of mobilization has become successful in terms of Environmental Justice in stopping a project (Aydin et al. 2017). For instance, in Costa Rica, despite criminalization of activists, the court annulled the Crucitas mining project (EJatlas 2014e) and in El Salvador, despite the murders, the struggles against El Dorado mining project lead to a new law banning all types of metal mining activities in the country (EJatlas 2017c). From the total cases accounted for, 34% end in a court decision favorable to environmental defenders and 27% end in resolutions against them. The rest remains unknown or yet to be decided. To analyze structural and cultural violence, we focus on cases of failure, where visibly weak institutions decide passively or actively against environmental defenders and environmental justice.

In Guatemala, despite the fact that the National Attorney General’s Office declared the concession given to Perenco (a British–French company) illegal for oil exploitation in Laguna del Tigre, the project continues (EJatlas 2015c). The National Attorney argued that the concession was given within the Mayan Biosphere Reserve, which is also part of a Ramsar protected area. Regardless, in 2008 the Government promulgated FONPETROL, a law that guarantees the concession to Perenco if “the economic terms are favorable to the State”. Perenco, received the license for another 15 years more. This decision led to resistance by 53 communities that were already suffering from spills (resulting in water pollution, livestock, and crop losses); however, they were totally ignored. In 2010, the government established the “Green Batallion”, around 250 soldiers to protect the Laguna del Tigre but also to protect the company’s interests (EJatlas 2015c).

Furthermore, in Guatemala, the Polochic Valley case (EJatlas 2014f) shows how structural and cultural violence are present. For years, the state used its force and different powers (legislative, executive, and judicial), to repress local people and facilitate extractive projects such as sugarcane and oil-palm expansion. In 2011, the government participated actively in the process of eviction of indigenous families of the Valley. A judge ordered the eviction of 14 communities at the request of an oligarchic family to plant sugarcane. The Public Ministry (the state agency in charge of executing court orders, somehow equivalent to an attorney general) participated in the evictions as well as soldiers and national police. The oligarchic family pressured the military into burning crops and they decided an exact date and time for the evictions. Around 800 families were violently evicted, the National Civil Police killed one peasant, dozens of people were injured, and the homes and 1800 hectares of staple crops were razed or destroyed. At the same time, the government, using the media, accused organizations of being radicals that systematically implemented illegal measures. In a way, this is a century old conflict. Local communities have tried to recover the land they had lost from the beginning of the colonial era, through liberal reforms and the development of the agro-export model of cotton, banana, beef, and coffee farming.

The last example is located in Nicaragua, and it combines structural, cultural violence, and direct violence. In 1987, as part of the negotiations after many years of internal conflict, the government created the Autonomous Regions of the Atlantic (RAA-North and RAA-South) and conferred its management to the indigenous Miskito. These lands are protected under Law 445, which recognizes “indigenous communal property” and established that these lands are inalienable, immune to seizure, and exempted from taxes. Nevertheless, the increase of settlers willing to expand their businesses, wood smugglers, and ranchers is threatening the local population’s livelihoods and leading to land disputes over the last decades. Miskitos call for Tasba Pri which opposes the notion of “economic development”. Tasba Pri means “Free Land” and the right to continue their sustainable and ancestral activities such as agriculture and fishing. In response of resistance, direct violence such as fire attacks, kidnappings, tortures, and murders has been denounced by the Miskito (EJatlas 2017d). To escape, indigenous groups have crossed the border looking for refuge in Honduras. In total, 3000 people have been displaced and at least 32 indigenous people killed. For Miskito—as for indigenous from the Polochic Valley—these events hark back to another time when they battled the leftist Sandinista government in a quest to keep their land in the civil war in the 1980s. Up to now, we have described examples of the Galtung’s triangle of direct, structural, and cultural violence. In the following section, we identify less visible and accumulative forms.

Slow violence

Human exposure to unknown and/or uncertain risks is reported in 14% of the cases, deaths as health impacts in 24%, water pollution in 60%, and air pollution, and soil contamination in 45%. Overall, these health and environmental impacts are forms of violence to both humans and nature. Not only environmental defenders but surrounding communities and future generations are affected since hazardous substances can accumulate in future bodies and threaten newborns before conception (Monge et al. 2007). Contrary to direct or structural violence, data do not show remarkable differences between countries. We see slow violence exemplified through cases of monoculture—one of the most common type of conflict in Central America—where pesticides in water, air, and soil slowly enter and accumulate in human bodies and the environment. The resistance appears only after impacts become visible, if at all. The next regional case in the “banana republics” (Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and Honduras) exemplifies this.

Nowadays, ex-banana workers are still mobilizing for compensation due to the effects of exposure to dibromochloropropane (DBCP), a nematicide used to kill worms on the banana plants owned by the United Fruit company during the seventies. The chemical was produced by Dow Chemical and Shell Oil Company (EJatlas 2016d, e, f). Years after exposure, surrounding communities of the banana plantations realized an increasing amount of premature abortions, birth defects, or congenital anomalies and an increasing number of sterile men. Once the chemical was proven to be the cause of their health damages, banana workers began a mobilization to ask for compensation. However, nowadays and after decades of struggle (in national and international courts), most people have not received compensation from the companies. The efforts to sue the producers and users of the chemical have faced difficulties, unleashing a circle of injustices due to the power asymmetries between the multinationals and the local people in terms of scientific support, general information, relation with state institutions, and lawyers. According to affected communities, there has been a great failure in the institutional arrangements for enforcing liability for damages to health.

Ecological violence

Ecological violence focuses on nature, but humans through protesting and public campaigns play a role in making it visible. For instance, the ecological effects of DBCP remain unknown, and conflicts have mainly focused on the human impact. Ecological violence is generalized along the conflicts in the region. Biodiversity loss, deforestation, and loss of vegetation cover are reported as an impact in 80% of the cases, water pollution, decreasing water quality and reduced ecological and hydrological connectivity in 60%, and air pollution and soil contamination in 45%.

To draw on this dimension of violence, we focus on two key examples. The first one is in Costa Rica, where “shark finning” became an illegal practice. Shark finning involves catching the shark from the sea, cutting its fins off, and throwing the rest of the body back to the sea, where the shark slowly dies. This cruel practice is related to demand for fins in Asian markets, where dishes such as shark fin soup are popular. Against this, national and international organizations and universities have strongly denounced it, leading to mass mobilization, calling for new and stricter legislation but also encouraging consumer boycott (EJatlas 2016g).

The second example of ecological violence (combined with extreme direct violence against humans) is located in Guatemala, where a high degree of pollution in La Pasión River was caused by the spillage of malathion, a chemical used in oil-palm plantations (EJatlas 2015d). After the spillage, there was a high impact on the aquatic ecosystem; neighboring villagers saw the river full of dead fish and used the word “ecocide” in their public campaigns against pollution of the river and claims for decontamination. The company (REPSA), owner of the oil-palm plantations and responsible for the use of the chemical, did not take actions. Concerned with this, Rigoberto Lima Choc—an inhabitant from the community—denounced the company, and finally, the local government took some actions against it. Days after, Rigoberto was found murdered, but no investigations were carried out to find the culprits. According to local community members, Rigoberto’s murdered was related to his decision to denounce the company (EJatlas 2015c).

In this section, we have shown with specific cases from the EJAtlas how different forms of violence are present and how some of them overlap. We perceive how in some countries, violence is more visible than in others, governments and companies are the main actors and how resistance is carried out by local communities and environmental defenders. These cases indeed support our hypothesis, the need for a wider, and more complex comprehension of violence to address the study of environmental conflicts.

Discussion: the need for a multidimensional violence approach

Causes of environmental conflicts are multifold. Empirical studies have shown how the extraction of raw materials and energy production and supply has an effect in the increase of environmental conflicts (Martinez-Alier et al. 2010; Muradian et al. 2012; Pérez-Rincón et al. 2017, this feature). This argument is highly consistent with our data, as the majority of the conflicts are related to mining, hydropower supply and the expansion of monocultures. One difference with other regions in Latin America (Pérez-Rincón et al. 2017, this feature; Teran 2017, this feature) is that conflicts related to oil and gas exploration and extraction which lead to “petro-violence” (Watts 2001) are less common in Central America.

Environmental conflicts are also a result of structural and cultural dynamics; for instance, the unequal distribution of economic benefits and environmental consequences influenced by coloniality, racism, class and gender inequalities (Martinez-Alier and O’Connor 1996), clashes of values over nature (Martinez-Alier 2009), or lack of participation and the non-recognition of communal institutions (Schlosberg 2013; Walter and Urkidi 2017). Environmental conflicts can arise suddenly or be a result of a long social cost-shifting process (Kapp 1950; Teran 2017, this feature). Regardless of the causes, different forms of violence appear and overlap throughout environmental conflicts.

Central American data report incidences of murders, evictions, and tortures; however, these are not isolated cases around the world (Del Bene et al. this feature; Global Witness 2015). Our findings go hand in hand with Global Witness reports, highlighting Guatemala and Honduras—countries with the poorest social and economic indicators in the region—as the most directly violent (Global Witness 2016). Why and under which conditions some conflicts are more directly violent than others deserves more attention. The historical conjuncture (Peluso and Watts 2001) and differences in the democracy index (Van der Borgh and Terwindt 2014) indicators might give further insight.

Overall, it is a constant that environmental defender murders remain impune (Global Witness 2016) and our data show how governmental institutions are not neutral actors in this, not only as they fail to ensure justice by passively ignoring to investigate murders, but also by taking part in evictions such as the conflict in the Polochic Valley (EJatlas 2014f) and by not respecting their own laws such as the Miskito case (EJatlas 2017d). Weak institutions and strong elites in some Central American countries (Bull 2014) are certainly factors to explain how environmental injustices are produced and reproduced.

Overall, powerless social groups such as indigenous, afro-descendants, and peasants from rural areas are the most impacted, the same groups who were impacted by internal wars decades ago (Kay 2001; Sibrián and Van der Borgh 2014; Mingorría 2017). For instance, Miskito in Nicaragua relates their resistance today to their past struggles. In Guatemala, Wayland and Kuniholm (2015) show how the memory of the war plays a role in the social cohesion to resist against mining and hydroelectric dams.

Despite the region’s internal differences, instances of ecological and slow violence are more homogenous. Historical factors or social and economic indicators do not seem to be related to these forms of violence. Costa Rica—with a high level of democracy and with a peaceful history—is one the largest consumers of pesticides. This issue is leading to high levels of diseases in rural settings (Monge et al. 2007) of which the DBCP episode was a tragic early example (Thrupp 1991). Even if there is not an immediate killer, these biocides (Carson 1962) or “slow murders” (Narain 2007) are culprits of slow violence (Nixon 2011) due to the daily contamination and the slow deaths they provoke. However, in the environmental conflicts studied, resistance is organized once the impacts in bodies have been felt and not before or during the slow violence.

Nowadays, even though the DBCP was banned, it is still causing impacts on human health (Bohme 2015). However, the impact it is causing on nature remains unknown. Environmental conflict cases in Central America also show how ecological violence can be manifested twofold; it can be both slow (daily and slow contamination, or loss of wildlife in rivers cutoff by dams) or direct (by a specific action such as cutting the shark fins).

Furthermore, different forms of violence can overlap in a single conflict, and in addition, one form of violence can lead to another. Due to the protest against ecological violence in Rio La Pasión, Rigoberto Lima Choc was shot dead. Moreover, banana workers still protesting for compensation have faced structural violence on the weak institutional systems that slowly ignored their need for a compensation (Boix 2007; Bohme 2015).

Also, Central America shows the key role of women as environmental defenders. Berta Cáceres was one key example, but there are many more in the region and around the world (Martinez-Alier and Navas 2017). Studies on gender and violence in environmental conflicts become relevant for this debate, more specifically women who deploy a twofold resistance against extractive companies and against patriarchal structures in their own homes and communities (Shiva 1994; Veuthey and Gerber 2010; Jenkins 2017).

Finally, most environmental defenders not only defend nature, because they depend on it, but also because their own values are congruent with this defense (Martinez-Alier 2002, 2009). Concepts such as “Tasba Pri” in Nicaragua closely relate with the Andean notion of Sumak Kawsay (Acosta 2013), and can lead to a wider discussion about not only cultural violence (the use of language to legitimize violence), but also the colonial, racist violence imposed by the dominant western narrative of “development” (Escobar 2011), where indigenous peoples are depicted as “backward” and their communal institutions are seen as “obstacles to progress and development”.

In this article, we aimed at viewing violence from a wide perspective, since a narrow view of violence will lead to misinterpretations of how violence operates in different countries and political and economic contexts. To approach this, we propose a multidimensional violence approach that we defined as “a focus in which violence is defined as an action or a process that appears in visible and unseen forms against humans, nature, and its sustainable relation”. In this article, multidimensional violence is an aggregate of direct violence, cultural, structural, slow, and ecological violence but other forms might also be added (and some might be missing) depending on the context in which environmental conflicts are embedded. For instance, other forms can be added such as gender violence in environmental conflicts. Furthermore, the forms of violence that are mentioned can be more complex; for instance, direct violence can be subdivided in different degrees of intensities (one murder or 90 murders makes a difference). Similarly, ecological violence can be both slow and direct. Furthermore, one dimension of violence can lead to the other and resistance can be deployed before or after one of these forms of violence is applied.

Conclusion

Drawing on literature in political ecology and environmental conflicts, studies of violence and rich empirical evidence from 95 environmental conflicts in Central America recorded in the EJAtlas, we have shown how different dimensions of violence appear and overlap in different historical, political and economic contexts. Violence in its different dimensions becomes visible due to movements of resistance and claims by environmental defenders in environmental conflicts. Regional and worldwide databases fed both by academics and activists are also useful to increase their visibility. However, there are dimensions of violence that are manifested in these conflicts that still remain unseen—even for environmental defenders. Daily violence such as slow violence and violence against nature might not be crude types of violence but are also threatening livelihoods, humans, and nature, even though resistance is only deployed once the impacts have been felt. Violence goes beyond individual environmental defenders to impact communities as a whole, nature itself and the human–nature interaction. In this article, we have proposed the need for a multidimensional violence approach (encompassing “slow”, structural, cultural, and ecological forms of violence, and not only direct quick episodes of physical violence) as a tool for a wider conceptualization of violence for analysis of environmental conflicts.

Notes

Environmental defenders are people who take peaceful action to protect land or environmental rights, whether in their own personal capacity or professionally (Global Witness 2017).

Due to the large sample size, these conflicts give a reliable picture of the environmental conflicts in the region. But, with a growing number of cases, some results might change.

The term was first mention in the novel “Cabbages and Kings” (Henry 1904) to describe the imaginary country of Anchuria inspired by the author’s experiences in Honduras.

People involve themselves in the regional struggles as activists or academics or both. We got in touch with Centro Humboldt and Nicaraguan Social Movement (Nicaragua); Panama Ecological Voices (Radio Temblor), the Environmental Advocacy Center (CIAM) and Alianza para un Mejor Darién (AMEDAR) (Panamá), the Salvadoran Center for Appropriate Technologies CESTA - Friends of the Earth; Justice and Freedom Movement (Honduras), Institute of Agrarian and Rural Studies IDEAR-CONGCOOP, the Central American Institute of Fiscal Studies in Guatemala and Madre Selva.

The data base has received contributions of scholars and activists representing a mixture of academic and grassroots organizations whose names appear in the last part of the data sheet.

Ejatlas classifies conflicts according to ten mutually exclusive primary categories (Nuclear power, Mineral Ore Extraction, Water management, Biomass and land conflicts, Fossil Fuels and Climate Justice, Infrastructure and Built Environment, Waste management, Biodiversity conflicts, Tourism, and Industrial and Utilities conflicts). There are many more secondary categories. For instance, under Nuclear Power conflicts (of which, incidentally, there are none from Central America in the EJAtlas), there could be conflicts classified under Uranium Mining, Nuclear Power Plants, or Nuclear Waste Disposal).

References

Acosta A (2009) La maldición de la abundancia. CEP, Swissaid and Abya Yala, Quito

Acosta A (2013) El buen vivir, Sumak Kawsay una oportunidad para imaginar otros mundos. Icaria, Barcelona

Aguilar-Støen M (2015) Staying the same: transnational elites, mining and environmental governance in guatemala. In: Bull B, Aguilar-Støen M (eds) Environmental politics in Latin America: elite dynamics, the left tide and sustainable development. Routledge Studies in Sustainable Development, London, pp 131–149

Aydin CL, Özkaynak B, Rodríguez-Labajos B, Yenilmez T (2017) Network effects in environmental justice struggles: An investigation of conflicts between mining companies and civil society organizations from a network perspective. Plos One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180494

Azpuru D (1999) Peace and democratization in Guatemala. Two parallel processes. In: Arnson CJ (ed) Comparative peace processes in Latin America. Woodrow Wilson Center Press, Washington, pp 97–126

Bebbington A, Bury J (2013) Subterranean struggles: new dynamics of mining, oil, and gas in Latin America. University of Texas Press, Austin

Bohme S (2015) Toxic injustice, a transnational history of exposure and struggle. University of California Press, California

Boix V (2007) El Parque de las Hamacas, el químico que golpeó a los pobres. Icaria, Barcelona

Brockett C (2005) Political movements and violence in Central America. Cambridge University Press, New York

Bucheli M (2008) Multinational corporations, totalitarian regimes and economic nationalism: United Fruit Company in Central America, 1899–1975. J Bus Hist 50:433–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076790802106315

Bull B (2014) Towards a political economy of weak institutions and strong elites in Central America. ERLACS 97:117–128

Carson R (1962) Silent spring. Penguin, New Jersey

Del Bene D, Scheidel A, Temper L (this feature) More dams, more violence? Analysing global resistances and repression around conflictive dams through co-produced knowledge. Sustain Sci (under revision)

Edelman M, León A (2013) Cycles of Land Grabbing in Central America: an argument for history and a case study in the Bajo Aguán, Honduras. Third World Q 34:1697–1722. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.843848

Escobar A (2011) Encountering development. The making and unmaking of the third world. Princeton University Press, New Jersey

Faber D (1992) Imperialism, revolution, and the ecological crisis of Central America. Lat Am Perspect 19:17–44

Galtung J (1969) Violence, peace and peace research. J Peace Res 6:167–191

Galtung J (1990) Cultural violence. J Peace Res 27:291–305

Global Witness (2014) Deadly environment. London. https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/environmental-activists/deadly-environment/. Accessed 15 Feb 2017

Global Witness (2015) How many more. London https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/environmental-activists/how-many-more/. Accessed 15 Feb 2017

Global Witness (2016) On dangerous ground. London https://www.globalwitness.org/en/campaigns/environmental-activists/dangerous-ground/. Accessed 15 Feb 2017

Global Witness (2017) Defenders of the earth: global killing of land and environmental defenders in 2016. Global Witness, London

Grandia L (2006) Land dispossession and enduring inequity for the Q’eqchi’ Maya in the Guatemalan and Belizean frontier colonization process reactions. UC Berkeley (PhD dissertation)

Jahan S (2016) Human development report 2016. United Nations Development Programme, New York

Jenkins K (2017) Women anti-mining activists’ narratives of everyday resistance in the Andes: staying put and carrying on in Peru and Ecuador. J Gender Place Cult 24:1441–1459. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1387102

Kapp W (1950) The social costs of private enterprise. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Kay C (2001) Reflections on rural violence in Latin America. Third World Q 5:741–775. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590120084584

Machado H (2014) Potosí, el origen: genealogía de la minería contemporánea. Mardulce, Buenos Aires

Martinez-Alier J (1995) Distributional issues in ecological economics. Rev Soc Econ 53:511–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346769500000016

Martinez-Alier J (2002) The environmentalism of the poor: a study of ecological conflicts and valuation. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham

Martinez-Alier J (2009) Social metabolism, ecological distribution conflicts, and languages of valuation. Cap Nat Soc 20:58–87

Martinez-Alier J, Navas G (2017) La represión contra el movimiento global de justicia ambiental: algunas ecologistas asesinadas. In: Alimonda H, Toro C, Martín F (eds) Ecología política latinoamericana: pensamiento crítico, diferencia latinoamericana y rearticulación epistémica (vol 2). CLACSO-Ciccus, Buenos Aires, pp 29–51

Martinez-Alier J, O’Connor M (1996) Ecological and economic distribution conflicts. In: Costanza R, Segura O, Martinez-Alier J (eds) Getting down to earth. Practical Applications of Ecological Economics Island Press, Washington, pp 153–183

Martinez-Alier J, Kallis G, Veuthey S, Walter M, Temper L (2010) Social metabolism, ecological distribution conflicts and valuation languages. Ecol Econ 70:153–158

Martinez-Alier J, Temper L, Del Bene D, Scheidel A (2016) Is there a global environmental justice movement? J Peasant Stud 43:731–755. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2016.1141198

McKay B, Fradejas A, Brent Z, Sauer WS, Xu Y (2016) China and Latin America: towards a new consensus of resource control? TWQ J 5:592–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/23802014.2016.1344564

McSweeney K, Nielsen E, Taylor M, Wrathall D, Pearson Z, Wang O, Plumb S (2014) Drug policy as conservation policy: narco-deforestation. Science 343:489–490. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1244082

Mingorría S (2017) Violence and visibility in oil palm and sugarcane conflicts: the case of Polochic Valley, Guatemala. J Peasant Stud. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2017.1293046

Monge P, Wesseling C, Guardado J, Lundberg I, Ahlbom A, Cantor K, Weiderpass E, Partanen T (2007) Parental occupational exposure to pesticides and the risk of childhood leukemia in Costa Rica. Scand J Work Environ Health 33(4):293–303

Muradian R, Walter M, Martinez-Alier J (2012) Hegemonic and global shifts in social metabolism: implications for resource-rich countries. Glob Environ Chang 22:559–567

Narain S (2007) Conflicts of interest. My journey through India’s Green Movement. Viking, Gurgaon

Nixon R (2011) Slow violence and the environmentalism of the poor. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Peluso N, Watts M (2001) Violent environments. Cornell University Press, Ithaca

Pérez-Rincón M, Vargas-Morales J, Crespo-Marín Z (2017 this feature) Trends in social metabolism and environmental con icts in four Andean countries from 1970 to 2013. Sustain Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-017-0510-9

Rasch E (2017) Citizens, criminalization and violence in natural resource conflicts in Latin America. Eur Rev Latin Am Caribb Stud/Revista Europea De Estudios Latinoamericanos y del Caribe 103:131–142

Scheidel A, Temper L, Demaria F, Martinez-Alier J (2017 this feature) Ecological distribution conflicts as forces for sustainability: an overview and conceptual framework. Sustain Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-017-0519-0

Schlosberg D (2013) Reconceiving environmental justice: global movements and political theories. Environ Polit 13:517–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/0964401042000229025

Shiva V (1994) Close to home. Women reconnect ecology, health and development. Earthscan, London

Sibrián A, Van der Borgh C (2014) La Criminalidad de los Derechos: La Resistencia a la Mina Marlin. Oñati Socio-Legal Ser 4(1):63–84

Stenzel PL (2006) Plan Puebla Panama: An economic tool that thwarts sustainable development and facilitates terrorism. William Mary Environ Law Policy Rev 30(3):555–623

Svampa M (2013) “Consenso de los Commodities” y lenguajes de valoración en América Latina. Nueva Sociedad, Buenos Aires

Temper L, Bene D, Martinez-Alier J (2015) Mapping the frontiers and front lines of global environmental justice: the EJAtlas. J Polit Ecol 22:256–278

Teran E (2017 This feature) Inside and beyond the Petro-State frontiers: geography of environmental conflicts in Venezuela’s Bolivarian Revolution. Sustain Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-017-0520-7

The Economist (2016) The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index. https://www.eiu.com/topic/democracy-index. Accessed 13 Aug 2017

Thrupp LA (1991) Sterilization of workers from pesticide exposure: the causes and consequences of DBCP-induced damage in Costa Rica and beyond. Int J Health Serv 21(4):731–757

Urcuyo C (2014) La Estrategia China en Centroamérica. Issue Brief no. 08.25.14. Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, Houston, Texas. https://www.bakerinstitute.org/media/files/files/8e23106a/BI-Brief-082514-China_CentralAm_Spanish.pdf. Accessed 18 Dec 2018

Van Bronkhorst B, Demombynes G (2010) Crime and violence in Central America. World Bank Report available at http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTLAC/Resources/Eng_Volume_II_Crime_and_Violence_Central_America.pdf. Accessed 18 Dec 2018

Van der Borgh C, Terwindt C (2014) Introduction. In: NGOs under pressure in partial democracies. Non-governmental public action. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Veuthey S, Gerber J-F (2010) Logging conflicts in Southern Cameroon: a feminist ecological economics perspective. Ecol Econ 70:170–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.09.012

Walter M, Urkidi L (2017) Community mining consultations in Latin America (2002–2012): the contested emergence of a hybrid institution for participation. Geoforum 84:265–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.09.007

Watts M (2001) Petro-violence: community, extraction, and political ecology of a mythic commodity. In: Peluso N, Watts M (eds) Violent environments. Ithaca, Cornell University Press, New York, pp 189–212

Wayland J, Kuniholm M (2015) Legacies of conflict and natural resource resistance in Guatemala. Extract Ind Soc 3(2):395–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.exis.2016.03.001

Zierler D (2011) The invention of ecocide: agent orange, Vietnam, and the scientists who changed the way we think about the environment. University of Georgia Press, Georgia

List of cases from Environmental Justice Atlas:

EJaltas (2015d) Ecocide in River La Pasion, Guatemala In: Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/proyecto-minero-el-corpus-honduras. Accessed 15 Dec 2016

EJatlas (2014a) Hydroelectric Project Patuca III (Piedras Amarillas), Honduras. In: Atlas Environ Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/hydroelectric-project-patuca-iii-piedras-amarillas-honduras. Accessed 7 Jan 2017

EJatlas (2014b) Interoceanic Grand Canal project, Nicaragua. In: Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/gran-canal-nicaraguas-project. Accessed 7 Jan 2017

EJatlas (2014c) Los Micos Beach and Golf Resort Project. In: Atlas Environ Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/los-micos-beach-and-golf-resort-project-honduras. Accessed 7 Jan 2017

EJatlas (2014d) Oil palm plantations in the Bajo Agúan, Honduras. In: Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/oil-palm-plantations-in-the-bajo-aguan-honduras. Accessed 7 Jan 2017

EJatlas (2014e) Crucias, Costa Rica. In: Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/crucitas-costa-rica. Accessed 14 Jan 2018

EJatlas (2014f) Sugarcane cultivation and oil palm plantation in Polochic valley, Guatemala. In: Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/sugarcane-cultivation-and-oil-palm-plantation-in-polochic-valley-guatemala. Accessed 14 Jan 2017

EJatlas (2015a) Chixoy Dam and Rio Negro massacre, Guatemala. In: Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/chixoy-dam-guatemala. Accessed 14 Jan 2018

EJatlas (2015b) Offshore Oil drilling, Belize. In: Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/belizean-population-against-offshore-drilling-blue-hole. Accessed 8 Jan 2018

EJatlas (2015c) Oil Extraction in Laguna del Tigre, Guatemala. In: Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/laguna-del-tigre-peten-guatemala. Accessed 8 Dec 2016

EJatlas (2016a) Proyecto Hidroeléctrico Xalalá, Guatemala. Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/proyecto-hidroelectrico-xalala. Accessed 10 Jan 2018

EJatlas (2016b) Chalillo Dam, Belize. In: Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/chalillo-dam-belize. Accessed Jan 2018

EJatlas (2016c) Barro Blanco Dam, Panama. In: Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/barro-blanco-dam-panama. Accessed 8 Jan 2017

EJatlas (2016d) DBCP toxic exposure in banana plantations in Costa Rica In: Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/afectadas-por-el-nemagon-costa-rica. Accessed 10 Jan 2017

EJatlas (2016e) DBCP toxic exposure in banana plantations in Nicaragua In: Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/afectados-por-el-nemagon-nicaragua. Accessed 10 Jan 2017

EJatlas (2016f) DBCP toxic exposure in banana plantations in Honduras In: Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/afectados-por-el-nemagon-honduras. Accessed 10 Jan 2017

EJatlas (2016g) Shark Finning, Costa Rica. In: Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/shark-finning-o-aleteo-en-costa-rica. Accessed 17 Jan 2017

EJatlas (2017a) Proyecto Hidroeléctrico Agua Zarca, Honduras. In: Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/proyecto-hidroelectrico-agua-zarca-honduras. Accessed 10 Jan 2018

EJatlas (2017b) Oil palm and National Park Jeannette Kawas, Honduras. In: Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/jeannette-kawas-fernandez-case-honduras. Accessed 7 Aug 2017

EJatlas (2017c) Pacific Rim at El Dorado mine, El Salvador. In: Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/el-dorado-el-salvador. Accessed 8 Jan 2017

EJatlas (2017d) Dispute over Indigenous Miskito Lands, Nicaragua. In Atlas Environ. Justice. http://ejatlas.org/conflict/miskito-nicaragua. Accessed 7 Aug 2017

Acknowledgements

We thank Arnim Scheidel, Joan Martínez Alier, Giacomo D’Alisa, anonymous reviewers, and members of the ENVJustice Project for comments on the previous versions. We also thank collaborators of the EJAtlas in Central America, Francisco Venes, and Lena Weber for language revision. Grettel Navas and Sara Mingorría acknowledge support from the European Research Council (ERC) Advanced Grant ENVJustice (No. 695446).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handled by Arnim Scheidel, Erasmus University Rotterdam International Institute of Social Studies, International Institute of Social Studies (ISS), Netherlands.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Navas, G., Mingorria, S. & Aguilar-González, B. Violence in environmental conflicts: the need for a multidimensional approach. Sustain Sci 13, 649–660 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0551-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-018-0551-8