Abstract

Background

Associations between race/ethnicity and medications to treat OUD (MOUD), buprenorphine and methadone, in reproductive-age women have not been thoroughly studied in multi-state samples.

Objective

To evaluate racial/ethnic variation in buprenorphine and methadone receipt and retention in a multi-state U.S. sample of Medicaid-enrolled, reproductive-age women with opioid use disorder (OUD) at the beginning of OUD treatment.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Subjects

Reproductive-age (18–45 years) women with OUD, in the Merative™ MarketScan® Multi-State Medicaid Database (2011–2016).

Main Measures

Differences by race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, “other” race/ethnicity) in the likelihood of receiving buprenorphine and methadone during the start of OUD treatment (yes/no) were estimated using multivariable logistic regression. Differences in time to medication discontinuation (days) by race/ethnicity were evaluated using multivariable Cox regression.

Results

Of 66,550 reproductive-age Medicaid enrollees with OUD (84.1% non-Hispanic White, 5.9% non-Hispanic Black, 1.0% Hispanic, 5.3% “other”), 15,313 (23.0%) received buprenorphine and 6290 (9.5%) methadone. Non-Hispanic Black enrollees were less likely to receive buprenorphine (adjusted odds ratio, aOR = 0.76 [0.68–0.84]) and more likely to be referred to methadone clinics (aOR = 1.78 [1.60–2.00]) compared to non-Hispanic White participants. Across both buprenorphine and methadone in unadjusted analyses, the median discontinuation time for non-Hispanic Black enrollees was 123 days compared to 132 days and 141 days for non-Hispanic White and Hispanic enrollees respectively (χ2 = 10.6; P = .01). In adjusted analyses, non-Hispanic Black enrollees experienced greater discontinuation for buprenorphine and methadone (adjusted hazard ratio, aHR = 1.16 [1.08–1.24] and aHR = 1.16 [1.07–1.30] respectively) compared to non-Hispanic White peers. We did not observe differences in buprenorphine or methadone receipt or retention for Hispanic enrollees compared to the non-Hispanic White enrollees.

Conclusions

Our data illustrate inequities between non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White Medicaid enrollees with regard to buprenorphine and methadone utilization in the USA, consistent with literature on the racialized origins of methadone and buprenorphine treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Amid endemic structural racism affecting perinatal health in the USA,1,2 significant racial inequities in maternal-infant morbidity and mortality exist among reproductive-age people with opioid use disorder (OUD).3 Significant racial inequities in maternal-infant morbidity and mortality exist among reproductive-age people with opioid use disorder (OUD), evidenced by the number of pregnancy-related deaths among non-Hispanic black women (40.8 /100,000 persons) being 3.2 times the rate for non-Hispanic White peers (12.7/100,000).4 Overdose has been found to significantly contribute to rising maternal mortality and pregnancy-associated deaths.5 FDA-approved medications to treat OUD (MOUD), which include buprenorphine or methadone as the recommended MOUDs in pregnancy, are the standard of care for the treatment of OUD in people of childbearing age.6 However, there is inadequate access to and utilization of buprenorphine and methadone relative to demand among reproductive-age people in the USA.7,8 In an analysis of Massachusetts Medicaid claims, for instance, Non-Hispanic Black people were 63% less likely than non-Hispanic White peers to receive MOUD while pregnant, even after adjusting for other maternal characteristics.9,10 Lower MOUD receipt is also seen in non-pregnant historically marginalized patients during the postpartum period.11

In this study, we analyzed a multi-state sample of Medicaid-enrolled, reproductive-age people identified as female with OUD in the USA who were at the beginning of their OUD treatment trajectory. Our objective was to evaluate racial/ethnic variation in MOUD receipt and retention. We hypothesized lower rates of buprenorphine receipt and higher rates of methadone receipt among non-Hispanic Black Medicaid participants, relative to non-Hispanic White participants. We hypothesized lower rates of retention for both buprenorphine and methadone among non-Hispanic Black Medicaid enrollees relative to non-Hispanic White peers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using the Merative™ MarketScan® Multi-State Medicaid Database among reproductive-age, Medicaid-enrolled people, whose gender was identified as female in insurance claims. The MarketScan Research Databases include inpatient, outpatient, enrollment, and pharmacy claims representing paid clinical encounters and as previously described.12 Data were available from 1/1/2011 to 12/31/2016. This study was exempt from IRB review as no identifiable private data was used.

MarketScan Data Structure

The MarketScan data uses the “treatment episode” as the unit of analysis, defined by continuous insurance claims (i.e., fills, dispensing) without lapses in claims > 45 days. While previous analyses have employed conservative treatment 30-day continuation thresholds based on National Quality Forum performance criteria,13 others have used more liberal 60-day thresholds,14 and we selected 45 days given lack of consensus on 30- versus 60-day thresholds.15

Participants/Observation Window

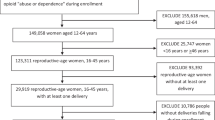

Our cohorts were derived from 150,712 people in the USA with Medicaid who had (1) at least one ICD 9/10 diagnosis for OUD (codes detailed in the Supplement) and (2) were at the beginning of their OUD treatment trajectory (buprenorphine, methadone, or psychosocial treatment for OUD), with the treatment claim accompanied by an OUD diagnostic code.12 All persons had 6 months minimum of pharmacy and medical coverage prior to the beginning of OUD treatment, as previous studies employed 6 months as a fixed baseline look-back period shared by all individuals for covariate assessment.16 We excluded people < 18 years or > 45 years of age (n = 28,559) in order to derive an analytic sample of reproductive-age adults (Fig. 1). We excluded those who received naltrexone (n = 15,553), as opioid antagonists are not currently the recommended standard of care for OUD treatment.17 We excluded people who received both buprenorphine and methadone in a single episode because we aimed to differentiate between buprenorphine and methadone utilization patterns (n = 1659) (Table 1).

Because pregnancy may be a motivator and facilitator of buprenorphine and methadone initiation and retention in reproductive-age women,18 we sought to classify pregnancy status per established methods,18,19 excluding those who became pregnant within 6 months (a benchmark for minimal treatment engagement in non-pregnant people receiving buprenorphine or methadone) of their first day of treatment (n = 1870). Our final sample included 66,550 people enrolled in Medicaid beginning treatment with buprenorphine, methadone, or psychosocial treatment only (without buprenorphine or methadone).

The primary predictor variable was race/ethnicity, for which we were limited by the racial/ethnic classifications provided by the Medicaid data.20 Self-reported20 race/ethnicity was operationalized as Hispanic vs non-Hispanic Black vs non-Hispanic White vs “Other.” The outcome variables were (1) buprenorphine or methadone receipt (“treatment initiation,” whether their first episode of OUD treatment involved receiving buprenorphine or methadone (yes/no) versus psychosocial treatment without buprenorphine or methadone,and (2) survival-time outcomes of time (days) until discontinuation of buprenorphine or methadone. Procedural and diagnostic codes for OUD treatments are shown in the Supplement.

The outcome variables were (1) treatment initiation and (2) treatment discontinuation. Buprenorphine or methadone initiation was defined as prescriptions during a new, continuous treatment episode that was not preceded by treatment claims for > 45 days. It was assumed that active prescription fills or procedure codes for buprenorphine or methadone connoted medication consumption.12

Covariates included age on the first date of treatment (in years), pregnancy status, and ICD9/10 diagnostic codes for the following: mood disorder (depression or bipolar disorder), anxiety disorders (composite of generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, social anxiety, and other dissociative, stress-related, somatoform, and other nonpsychotic disorders), or co-occurring SUDs (alcohol, cannabis, sedative-hypnotics[benzodiazepines/Z-drugs], stimulants[methamphetamines, cocaine], tobacco) (Supplement).

Statistical Analyses

First, we computed descriptive statistics, comparing age and clinical characteristics between people of different racial groups. Next, we performed two sets of logistic regression analyses at the treatment episode level to estimate associations between the predictor variable (race/ethnicity) and the outcome variable (whether first treatment episodes for OUD involved either buprenorphine or methadone, as opposed to psychosocial treatment without buprenorphine or methadone). To adjust for confounders, we fitted models including age, pregnancy status, and aforementioned co-occurring SUDs and psychiatric conditions. Because each person could have multiple treatment episodes, robust standard errors were estimated using Taylor series linearization.21 Next, among treatment episodes for people receiving buprenorphine or methadone, we used Kaplan–Meier models to estimate unadjusted time to medication discontinuation associated with race/ethnicity, with survival curves compared using log-rank tests. Follow-up time was calculated from the first date of buprenorphine or methadone to the date of discontinuation or censoring. We subsequently used multivariate Cox regression models to evaluate whether buprenorphine and methadone discontinuation varied according to race/ethnicity. Sensitivity analyses were conducted by limiting observations to one treatment episode per person. Given the heterogeneity in thresholds for treatment episode continuity used by other studies,15 we also conducted sensitivity analyses specifying episode continuity with 30- and 60-day gaps. P-values were two-sided, with a significance level of 0.05. All analyses were conducted via SAS version 9.4. Reporting of Studies Conducted Using Observational Routinely Collected Health Data Statement for Pharmacoepidemiology (RECORD-PE) reporting guidelines were followed.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Among 66,550 people with Medicaid enrollment spanning 107,292 treatment episodes (3.0% pregnant, average age 31.1 years), 641 (1%) identified as Hispanic, 3907 (5.9%) non-Hispanic Black, 55,975 (84.1%) non-Hispanic White, and 3497 (5.3%) “other” race/ethnicity. A total of 7191 (10.8%) had alcohol, 4750 (7.1%) amphetamine, 10,300 (15.5%) cannabis, 7251 (10.9%) cocaine, 4847 (7.3%) sedative, and 37,295 (56.0%) tobacco use disorders. A total of 28,426 (42.7%) had affective (major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder), 25,089 (37.7%) anxiety, and 1834 (2.8%) psychotic disorders.

Buprenorphine or Methadone Receipt

Among Medicaid enrollees who were at the beginning of their OUD treatment trajectory, 15,313 (23.0%) had buprenorphine and 6290 (9.5%) methadone.

A total of 32.9% (211/641) of Hispanic enrollees received buprenorphine or methadone versus 29.2% (1140/3907) of Non-Hispanic Black enrollees and 31.5% (17,612/55,975) of non-Hispanic White peers. For buprenorphine specifically, receipt rates spanned 22.5% (144/641), 15.2% (594/3,907), and 21.6% (12,100/55,975) for the Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic White cohorts respectively. In the case of methadone, receipt rates ranged from 10.5% (67/641) among Hispanic enrollees, 14% (546/3907) among non-Hispanic Black enrollees, and 9.9% (5512/55,975) among non-Hispanic White peers.

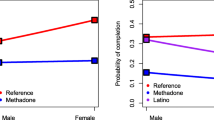

As shown in Fig. 2, non-Hispanic Black enrollees were less likely to be prescribed buprenorphine (aOR = 0.76 [0.68–0.84]) but had a higher likelihood of receiving methadone (aOR = 1.78 [1.60–2.00]) compared to non-Hispanic White enrollees. No significant differences in buprenorphine or methadone receipt were observed for Hispanic enrollees compared to the non-Hispanic White enrollees. These findings were robust in analyses that limited observations to one treatment episode per person, as well as sensitivity analyses specifying alternative definitions of treatment continuity (30- and 60-day) (Supplement).

MOUD Discontinuation

With regard to any MOUD, at 180 days, 59.5% (18,012/30,257) of episodes were discontinued (58.4% non-Hispanic White vs 61.9% non-Hispanic Black). Unadjusted log-rank tests showed racial differences in median buprenorphine or methadone discontinuation: 141 days Hispanic vs 123 days non-Hispanic Black vs 132 days non-Hispanic White enrollees (χ2 = 10.6; DF = 3; P = 0.01) (Fig. 3).

Unadjusted log-rank tests showed racial differences in median discontinuation for buprenorphine (137 days Hispanic vs 94 days non-Hispanic Black vs 111 days non-Hispanic White enrollees, χ2 = 18.4; DF = 3; P = 0.004) and methadone (154 days Hispanic vs 153-days non-Hispanic Black vs 183 days non-Hispanic White enrollees; χ2 = 10.9; DF = 3; P = 0.01).

Compared to the White non-Hispanic group, Non-Hispanic Black enrollees had increased discontinuation for MOUD, defined as buprenorphine or methadone, in adjusted models (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 1.11 [1.05–1.20]), as well as for buprenorphine (aHR = 1.16 [1.08–1.24]) and methadone (aHR = 1.16 [1.07–1.30]) separately. Similar findings were observed in sensitivity analyses limiting observations to one episode per person (Supplement). We did not observe differences in discontinuation of buprenorphine or methadone between Hispanic and non-Hispanic enrollees. Sensitivity analyses specifying treatment retention with 30- and 60-day gaps between episodes did not differ from parent analyses (Supplement).

DISCUSSION

In a multi-state sample of Medicaid-insured reproductive-age people who were at the beginning of their treatment for OUD in the USA, we show low buprenorphine and methadone prescription rates by the health care system—and high discontinuation rates—as well as racial inequities in buprenorphine and methadone utilization. We provide data depicting the existence of significant racial inequities in OUD treatment receipt and retention, supporting existing work that has found non-Hispanic Black pregnant people to be less likely to receive buprenorphine and methadone than non-Hispanic White peers, while expanding these findings into a multi-state sample of reproductive-age women.10 Our findings also lend support for previous studies that have found people of color are more likely than non-Hispanic White peers to access MOUD from publicly funded treatment programs dispensing only methadone,22 consistent with literature on the racialized origins23 of methadone and buprenorphine treatment. Whereas the structure of methadone treatment has its origins in state control and tight surveillance via DEA-regulated clinics, often described as more similar to the criminal justice system than community-based treatment,24 buprenorphine is prescribed via less surveilled outpatient environments.25 The requirement of daily, in-person methadone dosing is known to cause significant life disruption to people working towards recovery, interfering with education, job training, and sustained employment,26 in addition to methadone corresponding to higher burdens of adverse neonatal outcomes than buprenorphine.27 Notably, despite higher prevalence of methadone receipt, non-Hispanic Black enrollees were more likely to experience discontinuation for both buprenorphine and methadone compared to peers. Such elevated rates of treatment discontinuation among non-Hispanic Black enrollees are important to note, as longer periods of retention are strongly associated with decreased overdose risk in pregnant28 and non-pregnant29 people with OUD, which is especially salient as overdoses now rank as the fourth leading cause of death among all Black women, exceeded only by cancer, cardiovascular disease, and COVID-19.30

Our findings are consistent with previous research. An analysis of linked population-level statewide data in Massachusetts showed racial and ethnic disparities in the use of MOUD in pregnancy; non-Hispanic black and Hispanic women were significantly less likely to use MOUD compared to non-Hispanic White peers,10 in which similar disparities have been found in analyses in other states.31,32 These disparities may be contributing to worse peripartum and postpartum OUD morbidity,for instance, Martin and colleagues found an 11-fold increased risk of 12-month postpartum OUD morbidity (operationalized as OUD related hospital use) for non-Hispanic Black birthing people versus only twofold in White people.33

Ultimately, future studies are needed to evaluate unmeasured domains of influence beyond the individual level. In order to dissect mechanisms of the racial inequities observed in our analysis, future studies should employ perspectives of intersectionality, which is defined as a theoretical framework for understanding how people’s multiple identities relate to systems of oppression.34,35 Previous studies have documented racial inequities in access to buprenorphine providers by neighborhood,36 prescription rates,37 and timely receipt of medication,38 suggesting that structural causes of inequitable buprenorphine and methadone utilization by race/ethnicity run far deeper than the level of individual patients. As depicted by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Framework, multi-level research studies that impact multiple aspects of intersectionality—beyond insurance type at the individual level—are needed in order to improve OUD outcomes.34 For instance, at the interpersonal level, diagnostic bias, social networks and peer norms, and intergenerational trauma can worsen treatment outcomes.34,39 At the community and societal levels, medication utilization can be adversely affected by public stigma, limited community social capital, political disenfranchisement, and inaccessibility of mental healthcare that insurance status alone cannot solve.34,35 At the clinical and healthcare systems levels, interventions that integrate social services, community mobilization, and peer support with substance use disorder treatment—reaching beyond the level of the individual patient—have shown significant promise, which Hansen, Jordan, and colleagues emphasize is a lesson that the addiction treatment community can glean from AIDS activism.40 Traditionally, interventions to achieve health equity have focused on behavioral modification at the level of the individual patient while neglecting institutions, community, and societal contexts. In recent years, community-based research methods have been seeking to value the voices of patients from historically marginalized groups while addressing racism in study design, analysis, and dissemination. Interventions such as group prenatal care have shown significant promise in enhancing social support, increasing the amount of time spent with physicians, and improving physician knowledge of structural barriers to care, which may translate into greater systems-level change.41,42.

While our research is strengthened by its use of large-scale real-world claims data, several limitations need to be considered. For instance, Medicaid claims rely on self-reported race and ethnicity data within the constraints of available options for reporting at Medicaid enrollment. Although we found inequities between non-Hispanic White and non-Hispanic Black cohorts in buprenorphine and methadone utilization, we did not find such disparities in Hispanic enrollees. This may represent an underpowering of the Hispanic cohort, paralleling the low prevalence of Hispanic individuals in other studies using the MarketScan data.43,44 Previous analyses have found that asking separately about Hispanic origin and race, in self-report data, has not successfully led to the differentiation of ethnicity from race, with a large number of Hispanic respondents choosing “other” as their race.45 While more granular measures such as country of origin, language, and nationality may help improve our ability to differentiate between race and ethnicity, there continues to be concern for poor ascertainment of Hispanic individuals in administrative data, as well as Middle Eastern and North African populations that have traditionally been classified as “white” in federal datasets.45 While states can internally validate race/ethnicity in their Medicaid data, such validations are not available in the scientific literature,20 and a scoping review of over 2000 studies in the medical literature on maternal and infant outcomes among dyads affected by OUD, with no studies specifically defining race as a social construct.3 Whereas some states only collect voluntary information on self-reported race and ethnicity, several states are also known to impute missing data using language, geography, or matching with other state data,given such heterogeneity in data collection methods, there have been increasing calls for improving the standardization for collection, derivation, and validation of race/ethnicity in administrative data research.20

In addition, our generalizability is limited by the age of the data (pre-2016 and thus preceding contamination of drug supplies by fentanyl). As buprenorphine inductions in people struggling with addiction to fentanyl have increasingly been complicated by secondary peaking and nonlinear withdrawal, these analyses need to be replicated using up-to-date data.46 Our analyses are also limited by a lack of geospatial data to study factors such as geographic access (i.e., commute time,47 state-wide insurance policies,48 and provider shortages.49 Medicaid eligibility may vary across states, and our dataset does not contain state-level data,we are thus unable to address state or geographic fixed effects to account for state-to-state variation. Future studies should also evaluate the role of provider and setting characteristics50 that may account for the racial disparities observed, especially since Medicaid patients, encompassing a high prevalence of individuals from historically marginalized communities, have been found to be reliant on specialty treatment programs known to underuse evidence-based opioid agonist treatments.37 Our data curation required a 6-month period of insurance coverage prior to OUD treatment receipt as a lookback time frame for covariate ascertainment, which likely excludes patients experiencing discontinuity in insurance coverage and rendering our cohort a “best case scenario” population (despite its low buprenorphine and methadone utilization rates),even though our cohort is one that has substantial contact with the healthcare system, we nonetheless observed a low proportion of the sample receiving buprenorphine or methadone, illustrating how difficult access to opioid agonist medications is. Another limitation is that prescription coverage and medication fills do not always reflect actual consumption of medication. Finally, our data do not include pregnant patients with OUD who received withdrawal management with buprenorphine or methadone (as opposed to pharmacotherapy to treat OUD), a population at risk of worse treatment outcomes and warranting further study.51

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we evaluate a multi-state sample of reproductive-age Medicaid-enrolled people with OUD; our findings raise concern about low buprenorphine and methadone utilization, which is discordant with the present standard of care for OUD. In an era of rising morbidity and mortality from OUD among people of childbearing age in the USA, we depict racial inequities in buprenorphine and methadone receipt and treatment retention in a multi-state sample of people with (public) insurance enrollment. Examinations of factors that include patient, provider, program, community, state, and federal systems are warranted to improve equitable access and retention to both methadone and buprenorphine among patients with opioid use disorder.

References

McLemore MR, Altman MR, Cooper N, Williams S, Rand L, Franck L. Health care experiences of pregnant, birthing and postnatal women of color at risk for preterm birth. Soc Sci Med. 2018;201:127-35. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.02.013

Crear-Perry J, Correa-de-Araujo R, Johnson TL, McLemore MR, Neilson E, Wallace M. Social and Structural Determinants of Health Inequities in Maternal Health. J Womens Health. 2021;30(2):230-5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2020.8882

Schiff DMW EC, Foley B, Applewhite R, Diop H, Goulland L, Gupta M, Hoeppner BB, Peacock-Chambers E, Vilsaint CL, Bernstein JA, Bryant AS. Perinatal Opioid Use Disorder Research, Race, and Racism: A Scoping Review Pediatrics. 2022;149(3). doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-052368

Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, Cox S, Syverson C, Seed K, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Pregnancy-Related Deaths - United States, 2007-2016. Mmwr-Morbid Mortal W. 2019;68(35):762-5. doi:DOI https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6835a3

Bruzelius E, Martins SS. US Trends in Drug Overdose Mortality Among Pregnant and Postpartum Persons, 2017-2020. JAMA. 2022;328(21):2159-61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.17045

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no.711 summary: opioid use and opioid use disorder in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(2):488-9.

Phillippi JC, Schulte R, Bonnet K, Schlundt DD, Cooper WO, Martin PR, et al. Reproductive-Age Women's Experience of Accessing Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder: "We Don't Do That Here". Women Health Iss. 2021;31(5):455-61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2021.03.010

Tiako MJN, Friedman A, Culhane J, South E, Meisel ZF. Predictors of Initiation of Medication for Opioid Use Disorder and Retention in Treatment Among US Pregnant Women, 2013-2017. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;137(4):687-94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/Aog.0000000000004307

Peeler M, Gupta M, Melvin P, Bryant AS, Diop H, Iverson R, et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Maternal and Infant Outcomes Among Opioid-Exposed Mother Infant Dyads in Massachusetts (2017-2019). Am J Public Health. 2020;110(12):1828-36. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/Ajph.2020.305888

Schiff DM, Nielsen T, Hoeppner BB, Terplan M, Hansen H, Bernson D, et al. Assessment of Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Use of Medication to Treat Opioid Use Disorder Among Pregnant Women in Massachusetts. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(5):e205734.

Gao YA, Drake C, Krans EE, Chen Q, Jarlenski MP. Explaining Racial-ethnic Disparities in the Receipt of Medication for Opioid Use Disorder During Pregnancy. J Addict Med. 2022. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000979

Xu KY, Borodovsky JT, Presnall N, Mintz CM, Hartz SM, Bierut LJ, et al. Association Between Benzodiazepine or Z-Drug Prescriptions and Drug-Related Poisonings Among Patients Receiving Buprenorphine Maintenance: A Case-Crossover Analysis. Am J Psychiat. 2021;178(7):651-9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20081174

Meinhofer A, Williams AR, Johnson P, Schackman BR, Bao Y. Prescribing decisions at buprenorphine treatment initiation: Do they matter for treatment discontinuation and adverse opioid-related events? J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;105:37-43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2019.07.010

Williams AR, Samples H, Crystal S, Olfson M. Acute Care, Prescription Opioid Use, and Overdose Following Discontinuation of Long-Term Buprenorphine Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder. Am J Psychiat. 2020;177(2):117-24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19060612

Dong HR, Stringfellow EJ, Russell WA, Bearnot B, Jalali MS. Impact of Alternative Ways to Operationalize Buprenorphine Treatment Duration on Understanding Continuity of Care for Opioid Use Disorder. Int J Mental Health Addict. 2022. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-022-00985-w

Brunelli SM, Gagne JJ, Huybrechts KF, Wang SV, Patrick AR, Rothman KJ, et al. Estimation using all available covariate information versus a fixed look-back window for dichotomous covariates. Pharmacoepidem Dr S. 2013;22(5):542-50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pds.3434

Jones HE, Chisolm MS, Jansson LM, Terplan M. Naltrexone in the treatment of opioid-dependent pregnant women: common ground. Addiction. 2013;108(2):255-6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12071

Xu KY, Jones HE, Schiff DM, Martin CE, Kelly JC, Carter EB, et al. Initiation and Treatment Discontinuation of Medications for Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnant Compared With Nonpregnant People. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141(4):845–853. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000005117

Bello JK, Salas J, Grucza R. Preconception health service provision among women with and without substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;230:109194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109194

Nead KT, Hinkston CL, Wehner MR. Cautions When Using Race and Ethnicity in Administrative Claims Data Sets. JAMA Health Forum. 2022;3(7):e221812. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.1812

Huang F. Analyzing group level effects with clustered data using Taylor series linearization. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2014;19(13):1–9.

Krawczyk N, Feder KA, Fingerhood MI, Saloner B. Racial and ethnic differences in opioid agonist treatment for opioid use disorder in a US national sample. Drug Alcohol Depen. 2017;178:512-8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.06.009

Jackson DS, Tiako MJN, Jordan A. Disparities in Addiction Treatment Learning from the Past to Forge an Equitable Future. Med Clin N Am. 2022;106(1):29-41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2021.08.008

Andraka-Christou B. Addressing Racial And Ethnic Disparities In The Use Of Medications For Opioid Use Disorder. Health Affairs. 2021;40(6):920-7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.02261

Hansen H, Roberts S. Two Tiers of Biomedicalization: Methadone, Buprenorphine, and the Racial Politics of Addiction Treatment. In Netherland J, editor, Critical Perspectives on Addiction. 2012. p. 79–102. (Advances in Medical Sociology). https://doi.org/10.1108/S1057-6290(2012)0000014008

Harris J, McElrath K. Methadone as Social Control: Institutionalized Stigma and the Prospect of Recovery. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(6):810-24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732311432718

Suarez EA, Huybrechts KF, Straub L, Hernandez-Diaz S, Jones HE, Connery HS, et al. Buprenorphine versus Methadone for Opioid Use Disorder in Pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(22):2033-44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2203318

Krans EE, Kim JY, Chen QW, Rothenberger SD, James AE, Kelley D, et al. Outcomes associated with the use of medications for opioid use disorder during pregnancy. Addiction. 2021;116(12):3504-14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15582

Wakeman SE, Larochelle MR, Ameli O, Chaisson CE, McPheeters JT, Crown WH, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Different Treatment Pathways for Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920622. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20622

Harris RA. Race, Overdose Deaths, and Years of Lost Life. Jama Pediatr. 2022;176(7):729-. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.1171

Austin AE, Durrance CP, Ahrens KA, Chen Q, Hammerslag L, McDuffie MJ, et al. Duration of medication for opioid use disorder during pregnancy and postpartum by race/ethnicity: Results from 6 state Medicaid programs. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2023;247:109868. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2023.109868

Martin CE, Scialli A, Terplan M. Unmet substance use disorder treatment need among reproductive age women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;206:107679. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107679

Martin CE, Britton E, Shadowen H, Bachireddy C, Harrell A, Zhao X, et al. Disparities in opioid use disorder-related hospital use among postpartum Virginia Medicaid members. J Subst Use Addict Treat. 2023;145:208935. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.josat.2022.208935

Alvidrez JL, Barksdale CL. Perspectives From the National Institutes of Health on Multidimensional Mental Health Disparities Research: A Framework for Advancing the Field. Am J Psychiat. 2022;179(6):417-21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.21100969

Barksdale CL, Perez-Stable E, Gordon J. Innovative Directions to Advance Mental Health Disparities Research. Am J Psychiat. 2022;179(6):397-401. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.21100972

Hansen HB, Siegel CE, Case BG, Bertollo DN, DiRocco D, Galanter M. Variation in Use of Buprenorphine and Methadone Treatment by Racial, Ethnic, and Income Characteristics of Residential Social Areas in New York City. J Behav Health Ser R. 2013;40(3):367-77. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11414-013-9341-3

Lagisetty PA, Ross R, Bohnert A, Clay M, Maust DT. Buprenorphine Treatment Divide by Race/Ethnicity and Payment. Jama Psychiat. 2019;76(9):979-81. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0876

Hadland SE, Bagley SM, Rodean J, Silverstein M, Levy S, Larochelle MR, et al. Receipt of Timely Addiction Treatment and Association of Early Medication Treatment With Retention in Care Among Youths With Opioid Use Disorder. Jama Pediatr. 2018;172(11):1029-37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.2143

Foster VA, Harrison JM, Williams CR, Asiodu IV, Ayala S, Getrouw-Moore J, et al. Reimagining Perinatal Mental Health: An Expansive Vision For Structural Change. Health Affairs. 2021;40(10):1592-6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2021.00805

Hansen H, Jordan A, Plough A, Alegria M, Cunningham C, Ostrovsky A. Lessons for the Opioid Crisis-Integrating Social Determinants of Health Into Clinical Care. Am J Public Health. 2022;112:S109-S11. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/Ajph.2021.306651

Carter EB, Mazzoni SE, Collaborative EW. A paradigm shift to address racial inequities in perinatal healthcare. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225(1):108-9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.04.215

Ickovics JR, Kershaw TS, Westdahl C, Rising SS, Klima C, Reynolds H, et al. Group prenatal care and preterm birth weight: Results from a matched cohort study at public clinics. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(5):1051-7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0029-7844(03)00765-8

Ali MM, Cutler E, Mutter R, Henke RM, O'Brien PL, Pines JM, et al. Opioid Use Disorder and Prescribed Opioid Regimens: Evidence from Commercial and Medicaid Claims, 2005-2015. J Med Toxicol. 2019;15(3):156-68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13181-019-00715-0

Dunphy CC, Zhang K, Xu LK, Guy GP. Racial-Ethnic Disparities of Buprenorphine and Vivitrol Receipt in Medicaid. Am J Prev Med. 2022;63(5):717-25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2022.05.006

Viano S, Baker DJ. How Administrative Data Collection and Analysis Can Better Reflect Racial and Ethnic Identities. Rev Res Educ. 2020;44:301-31. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732x20903321

Bird HE, Huhn AS, Dunn KE. Fentanyl Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion: Narrative Review and Clinical Significance Related to Illicitly Manufactured Fentanyl. J Addict Med. 2023. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000001185

Kleinman RA. Comparison of Driving Times to Opioid Treatment Programs and Pharmacies in the US. Jama Psychiat. 2020;77(11):1163-71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1624

Patrick SW, Richards MR, Dupont WD, McNeer E, Buntin MB, Martin PR, et al. Association of Pregnancy and Insurance Status With Treatment Access for Opioid Use Disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2013456. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.13456

Patrick S, Faherty LJ, Dick AW, Scott TA, Dudley J, Stein BD. Association Among County-Level Economic Factors, Clinician Supply, Metropolitan or Rural Location, and Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. Jama-J Am Med Assoc. 2019;321(4):385-93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.20851

Tiako MJN, Culhane J, South E, Srinivas SK, Meisel ZF. Prevalence and Geographic Distribution of Obstetrician-Gynecologists Who Treat Medicaid Enrollees and Are Trained to Prescribe Buprenorphine. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2029043. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29043

Terplan M, Laird HJ, Hand DJ, Wright TE, Premkumar A, Martin CE, et al. Opioid Detoxification During Pregnancy A Systematic Review. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;131(5):803-14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/Aog.0000000000002562

Acknowledgements

Nuri Farber MD and the Psychiatry Residency Research Education Program (PRREP) of Washington University; Laura Bierut MD and Patricia Cavazos-Rehg PhD of the K12 Career Development Award Program in Substance Use and Substance Use Disorder at Washington University; Jeremy Goldbach PhD and Kathleen Bucholz PhD of the Transdisciplinary Training in Addictions Research (TranSTAR) T32 Program of Washington University; Matthew Keller MS and John Sahrmann MA from the Center for Administrative Data Research (CADR) of Washington University. In addition, we acknowledge Matt Keller MS, John Sahrmann MS, and Dustin Stwalley MA and the Center for Administrative Data Research (CADR) at Washington University for assistance with data acquisition, management, and storage.

Funding

This project was funded by R21 DA044744 (Richard Grucza/Laura Bierut). Effort for some personnel was supported by grants T32 DA015035 (Kevin Xu, PI: Kathleen Bucholz, Jeremy Goldbach), K12 DA041449 (Kevin Xu, PI: Laura Bierut, Patricia Cavazos-Rehg), R25 MH11247301 (K Xu, PI: Nuri Farber/Ginger Nicol), K23 DA053507 (Caitlin Martin), K23 DA048169 (Davida Schiff), and R01 DA047867 (Hendrée Jones), but these grants did not fund the analyses of the Merative™ MarketScan® Multi-State Medicaid Database data performed by Dr. Xu. CADR is supported in part by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences via grants UL1 TR002345 (from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept: Xu, Carter, Schiff, Grucza.

Design: Xu, Carter, Schiff, Grucza, Jones, Kelly, Martin, Bierut.

Analysis of data: Xu.

Interpretation of data: Xu, Carter, Schiff, Grucza, Jones, Kelly, Martin, Bierut.

Drafting of manuscript: Xu, Carter, Schiff, Grucza.

Obtained funding: Grucza, Bierut.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Grucza, Bierut.

Critical revision for important intellectual content: Xu, Carter, Schiff, Grucza, Jones, Kelly, Martin, Bierut.

Dr. Kevin Xu was the only individual who had access to the data and the only one to perform analyses. All of the other authors did not have access to the data, although contributed to the interpretation of data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest. LJB is listed as an inventor on US Patent 8080371, ‘Markers for Addiction’, covering use of SNPs in determining the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of addiction. All other authors declare no financial interests. All authors do not have any financial or non-financial relationships with organizations that may have an interest in our submitted work.

Positionality Statement

The authors acknowledge that their social identities inevitably influence their science. Perinatal substance use disorders is an area that holds special significance for the lead author, as his medical training overlapped with a surge in maternal overdoses during the COVID-19 pandemic, which were concomitant with rollbacks in perinatal health access in Missouri. While the lead author, who identifies as a US Chinese-American male physician-scientist, has had lived experiences of racism, he has not been pregnant, nor has personally suffered from addiction, and seeks to approach this topic area with humility. He has thus worked to build an interdisciplinary team of co-authors with a diverse array of backgrounds and areas of clinical expertise. The majority of authors, including the co-last author, are female scientists. The authors’ academic ranks include full professor, associate professor, assistant professor, and instructor/new faculty member. The institutions where the authors are employed span private universities, public universities, academic medical centers, public safety-net hospitals, and non-profit substance use disorder treatment centers in multiple states. As part of their commitment to rigorous antiracist science, the authors have sought to contextualize their results with conceptual models, cite prior work of scientists from historically marginalized groups, use people-first and affirming language, and thoroughly acknowledge the methodological limitations influencing their race/ethnicity data.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ebony B Carter, MD, MPH, and Richard A Grucza, PhD, share co-last authorship.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, K.Y., Schiff, D.M., Jones, H.E. et al. Racial and Ethnic Inequities in Buprenorphine and Methadone Utilization Among Reproductive-Age Women with Opioid Use Disorder: an Analysis of Multi-state Medicaid Claims in the USA. J GEN INTERN MED 38, 3499–3508 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08306-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08306-0