Abstract

Human-centered design (HCD), an empathy-driven approach to innovation that focuses on user needs, offers promise for the rapid design of health care interventions that are acceptable to patients, clinicians, and other stakeholders. Reviews of HCD in healthcare, however, note a need for greater rigor, suggesting an opportunity for integration of elements from traditional research and HCD. A strategy that combines HCD principles with evidence-grounded health services research (HSR) methods has the potential to strengthen the innovation process and outcomes. In this paper, we review the strengths and limitations of HCD and HSR methods for intervention design, and propose a novel Approach to Human-centered, Evidence-driven Adaptive Design (AHEAD) framework. AHEAD offers a practical guide for the design of creative, evidence-based, pragmatic solutions to modern healthcare challenges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Human-centered design (HCD) offers a novel approach for developing solutions to “wicked problems” in healthcare that involve complex interactions between population health demands, rapidly advancing technology, financial pressures, and workforce strain.1 By definition, wicked problems, such as childhood obesity, physician burnout, and access disparities, lack one-off solutions.2 Due to their complexity and interdependence, working to solve single aspects of these problems often affects other components,2, 3 and attempts to address multidimensional issues in public health and healthcare using traditional research methods lead to gaps between research and practice.2, 4 A framework integrating HCD principles and practices with evidence-grounded research methods has potential to generate interventions acceptable to stakeholders that positively influence outcomes of interest.4, 5

WHAT IS HUMAN-CENTERED DESIGN?

Human-centered design is an empathy-driven problem-solving approach with inspiration, ideation, and implementation stages.6 HCD examines human desirability (what the user really needs) and uses those insights to develop technologically and economically feasible solutions.6 The design process values “failing fast and often,” prioritizes outside-the-box thinking over prescribed processes to generate unique solutions, and has been increasingly used in fields like marketing and product design.6, 7 While HCD can rapidly produce pragmatic interventions, this approach typically does not integrate frameworks and rigorous methods central to evidence-based health services research. As such, adoption of HCD principles by health services researchers has been relatively slow.4

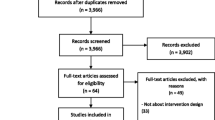

Two recent systematic reviews examine the emergence of HCD methods in healthcare. Both Altman 2018 (n = 24 studies) and Bazzano 2017 (n = 21 studies) noted the feasibility of using HCD in multiple healthcare domains and across diverse patient populations and conditions to produce solutions that may not be considered in traditional research settings. Both reviews found that most instances of HCD use in healthcare contexts were technology related. Importantly, the reviews noted discrepancies in quality and methodological rigor among the studies and found that few studies evaluated the solutions derived using HCD. Theevaluate care delivery in multidisciplinaryse limitations in HCD methods present barriers to wider healthcare acceptance and adoption.

HEALTH SERVICES RESEARCH METHODS FOR INTERVENTION DESIGN: STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

When used appropriately, health services research (HSR) methods produce effective, evidence-based interventions. Developed in response to complexities in modern healthcare settings, HSR utilizes qualitative and quantitative methods to improve and evaluate care delivery in multidisciplinary healthcare fields and considers psychosocial factors, access, cost, quality, and health outcomes8, 9 to test interventions. Recognized ways to deal with complexity and human uncertainty in HSR include consideration of concepts like causal inference,10, 11 treatment effect heterogeneity,12, 13 and regression to the mean.14 Theoretical frameworks, particularly those from implementation science,15,16,17 guide delivery and evaluation of interventions. HSR approaches incorporate rigorous testing and re-testing to lend credibility and proof of prior causality when designing new interventions; validated records of past failures and successes can inform predictive models and provide insights when considering solutions.

Employing HSR methods, however, does not ensure successful implementation and evaluation.4, 18,19,20 Implementation science has documented countless cases of failure to scale evidence-based interventions, and users often adapt interventions to suit their environment or needs, potentially affecting the fidelity of intervention delivery.21, 22 When brainstorming and designing interventions prioritizing spread or scale, traditional methods can prevent consideration of unique or creative solutions.4, 23 For example, focusing on “average patients” disadvantages patients who represent vulnerable minorities,24, 25 and designing for common healthcare scenarios overlooks insights from unusual or exceptional cases.7, 26

HUMAN-CENTERED DESIGN: STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

HCD addresses many gaps evident in HSR. Because the HCD process begins by exploring user desires and motivations, interventions developed using HCD may be more desirable and feasible to implement and sustain. HCD emphasizes the user’s (e.g., patient, provider, or caregiver) needs throughout the design process. By meeting users in spaces they live, work, or play; learning about their experiences; valuing their insights throughout the design process; and drawing inspiration from analogous fields, HCD exposes teams to unique possibilities and creative solutions.27,28,29,30 HCD nearly always involves interdisciplinary teams that harness expertise from diverse fields to provide a range of perspectives.27,28,29,30 Additionally, HCD typically uses rapid prototyping, testing, and iteration—a practical alternative to time- and resource-intensive steps required by traditional research.6 Public health research methods like Intervention Mapping and Community-Based Participatory Research (CBPR) also engage users and patients in intervention design processes.29, 31, 32 The distinction between these research methods and HCD lies in the nature of community involvement; CBPR values long-term, collaborative relationships between research teams and communities, while HCD focuses less on design team-community integration and more on gathering insights and involving stakeholders at strategic points to produce usable and desirable products or interventions.29

Applying HCD to healthcare settings presents challenges. Structures and ethical requirements within traditional academic settings such as institutional review boards (IRBs), legal contracting, and protection of confidentiality place necessary constraints on human-centered design teams, forcing compromises on a flexible and rapidly iterative process.5, 33 Funding agencies may be skeptical of HCD’s unconventional methods, although organizations like USAID and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation are beginning to support projects grounded in HCD.34 Finally, a lack of widespread understanding and variation from traditional research processes makes publication of HCD intervention work in peer-reviewed journals difficult, limiting the dissemination and long-term evaluation of such designs. Table 1 outlines the similarities and differences between traditional research and human-centered design.

AHEAD FOR HEALTH CARE: A PROPOSED FRAMEWORK

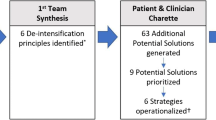

A framework combining principles of empathy-driven HCD with evidence-grounded HSR methods has the potential to generate pragmatic, high-impact healthcare interventions.4, 5 Fig. 1 presents an Approach to Human-centered, Evidence-driven Adaptive Design (AHEAD) for healthcare. This framework was initially developed for the Stanford Presence 5 project, which demanded a combination of HSR and HCD methods.35 Table 2 illustrates how the AHEAD framework was used in study activities for this project. Each component of AHEAD is described below. After defining a problem and assembling an interdisciplinary team, information gathering activities draw on evidence and inspiration to generate a knowledge base for synthesis. Guiding principles inform the design phase, which involves rapid iterations through brainstorming, prototyping, and testing cycles to develop an intervention that is subjected to rigorous evaluation.

Approach to Human-centered, Evidence-driven Adaptive Design (AHEAD). After defining a problem and assembling an interdisciplinary team (a), information gathering activities draw on evidence (b) and inspiration (c) to generate a preliminary knowledge base for synthesis (d). In the design phase, teams establish guiding principles (e) and ideate (f), which involves rapid iterations through brainstorming, prototyping, and testing cycles to develop an intervention that is subjected to rigorous evaluation (g).

Step 1: Define the Problem and Assemble a Team

What Problem is the Team Interested in Solving? Who Can Help Solve it?

In step 1 of AHEAD, elements from HCD and HSR are integrated to define the problem. These two processes approach problem identification from opposite ends of the inquiry spectrum. Health services researchers form defined research questions and hypotheses at the project’s outset and remain neutral and objective when working with subjects. In HCD, designers search for problems through need-finding activities. The design process often begins with in-depth exploration into user needs to identify a problem requiring a design solution. This approach leads to insights about overlooked problems but lacks the theoretical grounding and systematic approach of traditional research methods.5 In public health and healthcare settings, the process of need-finding might involve qualitative interviews with patients and physicians, which generate valuable themes and typically require IRB approval.5

Both HCD and HSR approaches have well-established methods for need-finding, but this process is given greater emphasis in HCD (which may explain one observation that interventions developed with design thinking have greater satisfaction, usability, and effectiveness than traditional interventions).30 Incorporating diverse perspectives is essential during problem identification—and assembling an interdisciplinary team is an integral part of AHEAD. Many reviews of HCD in health emphasize the importance of assembling a diverse team within and outside of academia and including stakeholders touching multiple problem aspects.27,28,29,30, 36 Purposeful assembly of interdisciplinary teams can prevent deviation toward familiar designs.27, 36, 37 HSR also values interdisciplinary teams, but team member expertise often stays within medical and academic fields. When using AHEAD, teams should include the expansive range of voices more typically found in HCD. For example, one project examining childhood asthma management included not only physicians and public health researchers on their team, but social workers and design scholars as well.38 Although each team member may have different roles and expertise, there should be one AHEAD team often works together instead of team members working separately on their expertise-specific components.

After assembling an interdisciplinary team, establishing a supportive, cohesive dynamic is essential.39 HCD emphasizes team building as equally as team assembly,7 while HSR often prioritizes assembly over cohesion. The field of team science identifies several characteristics of effective teams and strategies to strengthen team dynamics that can be applied within AHEAD.40 Broadly, interdisciplinary teams share a strong vision and goal; create communication channels for defining roles, assigning responsibilities, and resolving conflict; establish trust; and promote fun through team-building exercises and celebrations of success. Activities to strengthen team dynamics include highlighting individual strengths, checking in during group meetings, and setting the expectation that every team member can and should contribute.40

Step 2: Gather Information through Evidence and Inspiration

What is the Experience of Users Dealing with this Problem? What Strategies Have Been Tested in the Past?

After defining the problem and assembling a cohesive interdisciplinary team, the researchers begin information gathering to identify themes for potential solutions. In this phase, AHEAD incorporates methods from both HCD and HSR. Traditional research typically involves systematic or exhaustive reviews of the medical literature to examine previous evidence.41 In contrast, HCD inspiration activities use direct observation and immersion in the field to expose the design team to typical and unusual user experiences.5, 7, 27, 29, 30, 36 Teams can also observe and interview individuals outside healthcare who have “analogous experiences” (i.e., similar or relatable challenges) to describe or inspire solutions with implications in healthcare.27, 36, 42 AHEAD recommends reviewing existing research and evidence while also seeking inspiration from users (with special consideration for patients), extreme cases, and analogous fields to highlight themes or topics that may be overlooked in traditional evidence bases.

Step 3: Synthesize

What Common Themes Emerged from Information Gathering? What Values Will Guide the Team throughout the Rest of the Design Process?

Formative information gathering from evidence review and inspiration generates a comprehensive understanding of the problem and preliminary ideas about intervention structure and content. Next, in the synthesis phase, the team identifies emerging themes and insights arising from both methods or that showed up disproportionately in one over the other. This process should include critical review of gathered evidence to evaluate past successes and failures, consider how real users might react to potential interventions, and flag themes meriting further exploration.

After gathering evidence and inspiration from a wide range of perspectives, the team should solicit feedback from outside individuals on their synthesis and any conclusions drawn. HCD acknowledges the value of outside perspectives to avoid information silos and “groupthink” within teams.27, 43 HSR methods often use structured approaches for synthesis such as Delphi panels, a validated method for quantifying expert opinion through multiple rounds of independent ratings. Typically, researchers conduct Delphi panels to generate consensus around clinical guidelines or quality indicators,44, 45 but they can also be applied to the design of innovative healthcare delivery interventions.35 When seeking opinions, teams should include diverse voices (e.g., gender, race-ethnicity, and expertise) and gather both quantitative (e.g., rankings of feasibility) and qualitative feedback.

Step 4: Intervention Design: Guiding Principles and Ideation

How Can the Team Rapidly Iterate to Design a Meaningful Intervention?

Guiding Principles

After synthesizing findings and before entering the HCD-driven ideation phase, the team establishes guiding principles and defines the scope of the problem space for their intervention. Agreement on principles like the degree of evidence-backing, inclusiveness and sensitivity to diversity, and budgetary constraints helps ground and focus the team before ideation. HCD strategies for creating guiding principles include writing a team mission statement or brainstorming values that the intervention should reflect (e.g., easily adopted, minimal training, appropriate for diverse settings). Teams can also use more traditional frameworks to ensure that the intervention content aligns with an evidence-based or theoretical model. These HCD- and HSR-inspired activities also strengthen the collaborative dynamic established during team assembly.

Ideation

After establishing guiding principles, the research team goes through several rounds of ideation—rapid cycles of brainstorming, prototyping, and testing. In HSR contexts, researchers sequentially design and test a pilot before refining the intervention and studying it in a formal trial. In HCD, the ideation phase is characterized by flexibility and speed. The team aims for quantity rather than quality of ideas and creates sacrificial prototypes for learning purposes. This emphasis on creative output has proved successful in the business world; IDEO, a global design company, found that that when teams iterate on five or more ideas, they are 50% more likely to successfully launch a product or solution.46

Brainstorm During early prototype brainstorming, all ideas are welcome, and team members should suspend disbelief to extend creative boundaries. Brainstorming with multiple team members helps incorporate diverse perspectives and generate ideas rooted in different disciplines. Specific guidelines for brainstorming published by HCD leaders include sketching, movement between ideas posted around a room, and creation of and interaction with rough physical prototypes to boost creativity and generation of a large quantity of ideas (100 ideas in an hour-long brainstorming session is one recommended target).7 After brainstorming, preliminary ideas can be organized to combine ideas or elements of ideas in logical ways. This is best done visually (e.g., physically rearranging ideas on index cards) to reveal connections between ideas or concepts.7

Prototype The team then progresses to prototyping. Rapid prototyping refers to the cycle of quickly creating ideas out of cheap and disposable materials, soliciting feedback from potential or analogous users in a convenient setting, and incorporating that feedback to refine ideas and create new prototypes.7 Complementary activities include storyboarding (drawing the journey of the intended user interacting with the prototype)47,48,49 and role-playing (acting out the intended users’ interactions with the prototype).50 Prototype design sessions with users and stakeholders, including physicians, patients, family members, and health system leaders, can yield insights beyond those considered by the design team.36

Test After development, prototypes are tested with end-users. Unlike HSR, testing during ideation does not incorporate control groups or formal evaluation measures. This process is a low-cost and efficient way to gain insights about early prototypes. When applying these methods to healthcare settings, however, ethical considerations limit contact with patients and caregivers, and safety concerns often prohibit the use of rough prototypes in clinics. In some circumstances, it may be possible to test rapid prototypes with patient representatives or clinicians outside of clinical settings while staying compliant with IRB requirements.51,52,53 For example, after conducting patient needs assessment interviews, a group from the University of Chicago used testers demographically similar to patients at their target clinics to design a waiting room app for contraceptive counseling.51 This use of “analogous testers” proved successful; real patients using the app reported higher knowledge of contraceptive effectiveness and a greater interest in long-acting reversible contraceptive options.51 Another team ran participatory design sessions with a Patient and Family Advisory Committee (PFAC), comprised of leaders from various patient support groups the design team worked with in the need-finding phase, to design a dashboard displaying trends in prostate cancer care.52

After field testing, the research-design team can further develop the prototype to prepare for formal implementation and evaluation or take lessons learned and reenter the earlier stages of the ideation process.

Step 5: Evaluate

Does the Intervention Promote Positive Outcomes?

Once design activities are complete and the intervention is implemented, a rigorous evaluation should be conducted to examine the intervention’s effectiveness, as well as potential adverse consequences. A hybrid design54 that incorporates qualitative and quantitative methods can evaluate effectiveness across key outcomes (e.g., health outcomes, patient/provider experience, utilization, and costs) and generate important information about implementation (e.g., feasibility and fidelity, implementation costs, sustainability).55 Rigorous evaluation methods, including randomization when appropriate, increase the study’s credibility with health system leaders and policymakers and the likelihood that findings will be incorporated into future reviews and clinical guidelines, thereby leading to more widespread and lasting impact. Importantly, findings should also prompt reflection about and improvement of the intervention design.

DISCUSSION

This paper proposes a framework for integrating HCD and traditional HSR methods in the development of healthcare delivery interventions. Drawing on the strengths of both methods can counterbalance their individual limitations and facilitate the design of innovative, acceptable, and sustainable solutions in healthcare settings. Interventions derived using AHEAD have the potential to offer practical solutions to providers and healthcare managers due to the framework’s reliance on existing evidence and focus on stakeholder acceptability throughout the entire design process.

AHEAD builds on previous studies that examined opportunities to harness HCD for specific healthcare intervention design purposes. One study proposed “best practices” for using HCD to improve user experience with at-home health devices for patient users.28 These practices highlight aspects of design thinking that are valuable in designing for patients, such as the assembly of diverse, multidisciplinary design teams; centering design around empathy for users; developing deep understandings of tasks and setting; user involvement throughout the design process; and iteration through flexible prototype development.

Human-centered design has also been used in CBPR to design innovative solutions in collaboration with vulnerable populations.32 HCD focuses on understanding and designing for the user, while CBPR approaches intervention design through equal partnership between community members and researchers to define problems and identify solutions to improve health and reduce disparities.29, 56 HCD methods echoed in CBPR include co-creation, user engagement throughout design stages, and multiple rounds of iteration.29 One study used an approach that combined HCD and CBPR methods to address violence and other adversities that influence the health of Latinx youth. Engaging youth in design activities promoted dialogue between opposing individuals and groups and revealed opportunities for health promotion and change.57

Others have proposed combining HCD with implementation science to identify promising strategies for intervention design. For example, Dopp et al. conducted a conceptualization exercise in which a multidisciplinary panel of experts identified implementation science and human-centered design strategies that are similar or complementary and described how drawing on these disciplines might improve use of evidence-based practices.58 Two other examples are the SHIFT-Evidence framework (which focuses on three principles: “act scientifically and pragmatically”; “embrace complexity”; and “engage and empower”)59 and the Veterans Affairs’ Quality Enhancement Research Initiative,60 which focuses on addressing the “knowing-doing” gap, need-finding for problem definition, ongoing stakeholder engagement, and robust evaluation. These frameworks were designed with the goal of facilitating implementation of evidence-based practices. The AHEAD framework offers a unique contribution by drawing on principles of HCD that examine analogous fields and adjacent experiences when there is a clearly defined problem but limited evidence about potential solutions.

Innovating within the scientific method can be lengthy, inflexible, and resource-intensive, and proposed solutions often fail to address the users’ real needs. Development of the electronic health record (EHR) provides a stark example of consequences when users are excluded throughout the design process. Excluding providers from designing a system they use daily has had monumental consequences, with an association between physician EHR use and increased stress, burnout, and job dissatisfaction.61, 62 By including users from the outset, human-centered healthcare approaches can avoid similar disconnects. For example, one research team in Argentina used HCD techniques to redesign the alert system for drug-drug interactions in the EHR. After implementation, the new system resulted in fewer errors and unnecessary alerts and improved workload optimization and user satisfaction.63, 64

LIMITATIONS

This paper proposes a framework for integrating HCD and HSR to drive healthcare innovation. Our review of existing literature was scoping but not systematic in its approach, and may not have captured all existing HSR and HCD frameworks. Future research is needed to validate this framework and determine whether solutions derived achieve the desired and predicted effectiveness, implementation, and dissemination outcomes. Time and resource constraints may limit use of this framework, as well as gathering financial and institutional support needed to assemble interdisciplinary teams.40 Additionally, not all teams have access to collaborators with HCD expertise and contracting with outside design firms can be expensive.36 However, there are a growing number of academic institutions with design schools and many opportunities to gain exposure to design methodology and skills.65

CONCLUSION

Complex factors influencing population health and healthcare drive demand for innovative intervention design frameworks. An opportunity exists to integrate creative approaches from HCD with rigorous methods from HSR; the resulting AHEAD framework can guide the design of healthcare delivery interventions. Future efforts should examine whether interventions derived from this integrated framework generate effective solutions for “wicked” healthcare challenges.

References

Valeras AS. Healthcare’s wicked questions: A complexity approach. Fam Syst Health. 2019;37(2):187–9.

Rittel HWJ, Webber MM. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci. 1973;4(2):155–69.

Leischow SJ, Milstein B. Systems Thinking and Modeling for Public Health Practice. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(3):403-5.

Matheson GO, Pacione C, Shultz RK, Klugl M. Leveraging human-centered design in chronic disease prevention. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(4):472–9.

Bazzano AN, Martin J. Designing Public Health: Synergy and Discord. Des J. 2017;20(6):735-54.

Brown T. Design Thinking. Harv Bus Rev. 2008;86:84-92, 141.

IDEO;Pageshttps://www.designkit.org//resources/1 on December 3 2019.

Lohr KN, Steinwachs DM. Health Services Research: An Evolving Definition of the Field. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(1):15–7.

Pope C, Mays N. Reaching the parts other methods cannot reach: an introduction to qualitative methods in health and health services research. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 1995;311(6996):42–5.

Glass TA, Goodman SN, Hernan MA, Samet JM. Causal inference in public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2013;34:61–75.

Moser A, Puhan MA, Zwahlen M. The role of causal inference in health services research I: tasks in health services research. Int J Public Health. 2020;65(2):227–30.

Kravitz RL, Duan N, Braslow J. Evidence-based medicine, heterogeneity of treatment effects, and the trouble with averages. Milbank Quarter. 2004;82(4):661–87.

Duan N, Wang Y. Heterogeneity of treatment effects. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2012;24(1):50–1.

Morton V, Torgerson DJ. Effect of regression to the mean on decision making in health care. BMJ (Clin Res Ed). 2003;326(7398):1083–4.

Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):53.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50.

Glasgow RE, McKay HG, Piette JD, Reynolds KD. The RE-AIM framework for evaluating interventions: what can it tell us about approaches to chronic illness management? Patient Educ Couns. 2001;44(2):119–27.

Shelton RC, Cooper BR, Stirman SW. The Sustainability of Evidence-Based Interventions and Practices in Public Health and Health Care. Annu Rev Public Health. 2018;39(1):55–76.

Umscheid CA, Brennan PJ. Incentivizing “structures” over “outcomes” to bridge the knowing-doing gap. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):354–5.

Brownson RC, Graham AC, Proctor EK. Dissemination and implementation research in health: Translating Science to Practice. 2nd. New York: Oxford University Press; 2017.

Moore JE, Bumbarger BK, Cooper BR. Examining Adaptations of Evidence-Based Programs in Natural Contexts. J Prim Prev. 2013;34(3):147–61.

Glasgow RE, Vinson C, Chambers D, Khoury MJ, Kaplan RM, Hunter C. National Institutes of Health approaches to dissemination and implementation science: current and future directions. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1274–81.

Lyon AR, Koerner K. User-Centered Design for Psychosocial Intervention Development and Implementation. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2016;23(2):180–200.

Hutchins LF, Unger JM, Crowley JJ, Coltman CA, Jr., Albain KS. Underrepresentation of patients 65 years of age or older in cancer-treatment trials. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(27):2061–7.

Merlo J, Mulinari S, Wemrell M, Subramanian SV, Hedblad B. The tyranny of the averages and the indiscriminate use of risk factors in public health: The case of coronary heart disease. SSM Popul Health. 2017;3:684–98.

Bradley EH, Curry LA, Ramanadhan S, Rowe L, Nembhard IM, Krumholz HM. Research in action: using positive deviance to improve quality of health care. Implement Sci. 2009;4:25.

Roberts JP, Fisher TR, Trowbridge MJ, Bent C. A design thinking framework for healthcare management and innovation. Healthc (Amst). 2016;4(1):11–4.

Harte R, Glynn L, Rodriguez-Molinero A, Baker PM, Scharf T, Quinlan LR, et al. A Human-Centered Design Methodology to Enhance the Usability, Human Factors, and User Experience of Connected Health Systems: A Three-Phase Methodology. JMIR Hum Factors. 2017;4(1):e8.

Chen E, Leos C, Kowitt SD, Moracco KE. Enhancing Community-Based Participatory Research Through Human-Centered Design Strategies. Health Promot Pract. 2020 Jan;21(1):37–48.

Altman M, Huang TTK, Breland JY. Design Thinking in Health Care. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:E117.

Fernandez ME, Ruiter RAC, Markham CM, Kok G. Intervention Mapping: Theory- and Evidence-Based Health Promotion Program Planning: Perspective and Examples. Front Public Health. 2019;7:209.

Faridi Z, Grunbaum JA, Gray BS, Franks A, Simoes E. Community-based participatory research: necessary next steps. Prev Chronic Dis. 2007;4(3):A70–A.

Moody L. User-centred health design: reflections on D4D’s experiences and challenges. J Med Eng Technol. 2015;39(7):395–403.

Johnson T, Sandhu J, Tyler N. The Next Step for Human-Centered Design in Global Public Health. Stanford Social Innovation Review. 2019; October 22, 2019.

Zulman DM, Haverfield MC, Shaw JG, Brown-Johnson CG, Schwartz R, Tierney AA, et al. Practices to Foster Physician Presence and Connection With Patients in the Clinical Encounter. JAMA. 2020;323(1):70–81.

Dopp AR, Parisi KE, Munson SA, Lyon AR. A glossary of user-centered design strategies for implementation experts. Transl Behav Med. 2019 Nov 25;9(6):1057–1064.

Gawande A. Slow Ideas. The New Yorker. July 22, 2013. Accessed January 11, 2021. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/07/29/slow-ideas.

Martin MA, Press VG, Nyenhuis SM, Krishnan JA, Erwin K, Mosnaim G, et al. Care transition interventions for children with asthma in the emergency department. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(6):1518–25.

Edmondson A. Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Adm Sci Q 1999;44(2):350–83.

Bennett LM, Gadlin H. Collaboration and team science: from theory to practice. J Investig Med 2012;60(5):768–75.

Haverfield MC, Tierney A, Schwartz R, Bass MB, Brown-Johnson C, Zionts DL, et al. Can Patient–Provider Interpersonal Interventions Achieve the Quadruple Aim of Healthcare? A Systematic Review. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(7):2107–2117.

Schwartz R, Haverfield MC, Brown-Johnson C, Maitra A, Tierney A, Bharadwaj S, et al. Transdisciplinary Strategies for Physician Wellness: Qualitative Insights from Diverse Fields. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(7):1251–7.

Sterman JD. Learning from evidence in a complex world. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(3):505–14.

Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ. 1995;311(7001):376–80.

Murphy MK, Black NA, Lamping DL, McKee CM, Sanderson CF, Askham J, et al. Consensus development methods, and their use in clinical guideline development. Health Technol Assess. 1998;2(3):i-iv, 1–88.

Schwab K. Ideo Studied Innovation In 100+ Companies- Here’s What It Found. Fast Company; 2017.

Truong KN, Hayes GR, Abowd GD. Storyboarding: an empirical determination of best practices and effective guidelines. Proceedings of the 6th conference on Designing Interactive systems, 2006. 12–21.

McQuaid HL, Goel A, McManus M. When you can’t talk to customers: using storyboards and narratives to elicit empathy for users. Proceedings of the 2003 international conference on Designing pleasurable products and interfaces. Pittsburgh, PA, USA: Association for Computing Machinery; 2003:120–5.

Lin T. 2012;Pages. Accessed at Public Health Foundation at http://www.phf.org/phfpulse/Pages/Creating_Effective_Storyboards.aspx on February 29 2020.

Simsarian K. Take it to the next stage: the roles of role playing in the design process; 2003.

Gilliam ML, Martins SL, Bartlett E, Mistretta SQ, Holl JL. Development and testing of an iOS waiting room “app” for contraceptive counseling in a Title X family planning clinic. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(5):481.e1–.e8.

Hartzler AL, Izard JP, Dalkin BL, Mikles SP, Gore JL. Design and feasibility of integrating personalized PRO dashboards into prostate cancer care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):38–47.

Lin M, Hughes B, Katica M, Zuber C, Plsek P. Service Design and Change of Systems: Human-Centered Approaches to Implementing and Spreading Service Design; 2011.

Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C. Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care. 2012;50(3):217–26.

Landsverk J, Brown CH, Smith JD, Chamberlain P, Curran GM, Palinkas L, et al. Design and Analysis in Dissemination and Implementation Research. Dissemination and Implementation Research in Health. 2nd. New York: Oxford University Press; 2017.

Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3):312–23.

Kia-Keating M, Santacrose DE, Liu SR, Adams J. Using Community-Based Participatory Research and Human-Centered Design to Address Violence-Related Health Disparities Among Latino/a Youth. Fam Community Health. 2017;40(2):160–9.

Dopp AR, Parisi KE, Munson SA, Lyon AR. Aligning implementation and user-centered design strategies to enhance the impact of health services: results from a concept mapping study. Implement Sci Commun. 2020;1:17.

Reed JE, Howe C, Doyle C, Bell D. Successful Healthcare Improvements From Translating Evidence in complex systems (SHIFT-Evidence): simple rules to guide practice and research. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019;31(3):238–44.

Kilbourne AM, Goodrich DE, Miake-Lye I, Braganza MZ, Bowersox NW. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative Implementation Roadmap: Toward Sustainability of Evidence-based Practices in a Learning Health System. Med Care. 2019;57 Suppl 10 Suppl 3(10 Suppl 3):S286–s93.

Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Hasan O, Satele D, Sloan J, et al. Relationship Between Clerical Burden and Characteristics of the Electronic Environment With Physician Burnout and Professional Satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(7):836–48.

Kroth PJ, Morioka-Douglas N, Veres S, Babbott S, Poplau S, Qeadan F, et al. Association of Electronic Health Record Design and Use Factors With Clinician Stress and BurnoutElectronic Health Record Design and Use Factors and Clinician Stress and BurnoutElectronic Health Record Design and Use Factors and Clinician Stress and Burnout. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(8):e199609–e.

Luna D, Otero C, Risk M, Stanziola E, Gonzalez Bernaldo de Quiros F. Impact of Participatory Design for Drug-Drug Interaction Alerts. A Comparison Study Between Two Interfaces. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016;228:68–72.

Luna DR, Rizzato Lede DA, Otero CM, Risk MR, Gonzalez Bernaldo de Quiros F. User-centered design improves the usability of drug-drug interaction alerts: Experimental comparison of interfaces. J Biomed Inform. 2017;66:204–13.

Pope-Ruark R, Moses J, Tham J. Iterating the Literature: An Early Annotated Bibliography of Design-Thinking Resources. J Bus Tech Commun. 2019;33(4):456–65.

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation (#6382; PIs Donna Zulman and Abraham Verghese).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclaimer

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, or the Stanford University School of Medicine.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fischer, M., Safaeinili, N., Haverfield, M.C. et al. Approach to Human-Centered, Evidence-Driven Adaptive Design (AHEAD) for Health Care Interventions: a Proposed Framework. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 1041–1048 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06451-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06451-4