Abstract

Background

An important strategy to address the opioid overdose epidemic involves identifying people at elevated risk of overdose, particularly those with opioid use disorder (OUD). However, it is unclear to what degree OUD diagnoses in administrative data are inaccurate.

Objective

To estimate the prevalence of inaccurate diagnoses of OUD among patients with incident OUD diagnoses.

Subjects

A random sample of 90 patients with incident OUD diagnoses associated with an index in-person encounter between October 1, 2016, and June 1, 2018, in three Veterans Health Administration medical centers.

Design

Direct chart review of all encounter notes, referrals, prescriptions, and laboratory values within a 120-day window before and after the index encounter. Using all available chart data, we determined whether the diagnosis of OUD was likely accurate, likely inaccurate, or of indeterminate accuracy. We then performed a bivariate analysis to assess demographic or clinical characteristics associated with likely inaccurate diagnoses.

Key Results

We identified 1337 veterans with incident OUD diagnoses. In the chart verification subsample, we assessed 26 (29%) OUD diagnoses as likely inaccurate; 20 due to systems error and 6 due to clinical error; additionally, 8 had insufficient information to determine accuracy. Veterans with likely inaccurate diagnoses were more likely to be younger and prescribed opioids for pain. Clinical settings associated with likely inaccurate diagnoses were non-mental health clinical settings, group visits, and non-patient care settings.

Conclusions

Our study identified significant levels of likely inaccurate OUD diagnoses among veterans with incident OUD diagnoses. The majority of these cases reflected readily addressable systems errors. The smaller proportion due to clinical errors and those with insufficient documentation may be addressed by increased training for clinicians. If these inaccuracies are prevalent throughout the VHA, they could complicate health services research and health systems responses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

BACKGROUND

The USA is in the midst of an opioid use and overdose epidemic with a rising prevalence of opioid use disorder and incidence of opioid overdose deaths, with over 47,000 yearly.1 Veteran populations have been similarly impacted with 6485 veterans experiencing fatal overdose between 2010 and 2016, a 65% increase over that time.2 For people with moderate or severe opioid use disorder (OUD), treatment with medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) is associated with a decreased risk of overdose, yet a minority of people with OUD access treatment.3 Therefore, for both veteran and non-veteran populations, improving rates of treatment with MOUD for people at risk is an integral part of addressing the overdose crisis. Appropriately, increasing the proportion of veterans with OUD receiving MOUD is a priority within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).4

Increasing the proportion of veterans with OUD receiving MOUD requires clinicians to accurately identify and diagnose OUD. Inaccurate diagnoses due to misapplication or misunderstanding of diagnostic criteria for OUD are likely non-negligible.5 Given the relative lack of exposure to addiction curricula in medical education and associated stigma, non-addiction providers may be reticent to discuss opioid use and/or confused about the accurate application of DSM-5 criteria for OUD.6 Further confusion and inaccuracy arise from the discrepancy between DSM-5 OUD diagnoses and the available OUD diagnostic codes in ICD-10, opioid dependence (F11.2*) and abuse (F11.1*), which reflect out-of-date DSM-IV terminology.7,8,9 Finally, in practice, clinicians can apply a diagnostic code to an encounter reflecting a “suspected,” but not yet confirmed, diagnosis of OUD. Even if the patient subsequently is determined to not meet criteria for OUD, the diagnostic code attached to the initial clinical encounter remains in the medical record.

In addition to individual providers’ efforts to diagnose OUD, health care systems have an important role in proactively identifying patients with OUD and promptly referring them to treatment.4,10,11 Integrated health care systems now commonly use electronic health record data to identify individuals with OUD to measure how effectively they are referring people with OUD into care.12,13,14,15 Towards this goal, the VHA has implemented a publicly reported quality improvement OUD treatment metric using administrative data.4,16 This metric, the SUD16, is the proportion of veterans receiving MOUD among those with an OUD diagnosis in the past year and is used to identify underperforming VHA medical centers for intensified quality improvement efforts.4,17,18 It has been proposed that, similar to the VHA, Medicare include metrics of OUD treatment access and retention into its health system rankings.19

However, the development of quality metrics from administrative data relies on accurate coding of OUD diagnoses in the electronic medical record.20,21,22,23,24 Other chart validation studies of diagnoses in administrative data other than OUD have consistently found significant classification errors.25,26,27,28,29,30,31 It is unknown if ICD-10-based OUD diagnoses in administrative data are accurate. Our objective was to evaluate via chart review the documentation supporting new OUD diagnoses in VHA administrative data and to assess patient and treatment characteristics associated with potential misclassification.

METHODS

We conducted a chart verification study of a random sample of patients with new/incident OUD diagnoses. The study was part of a Department of Veterans Affairs Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) funded quality improvement project to increase MOUD prescribing rates in VHA medical centers in the New England region. Our study was limited to data extracted from the medical records obtained from sites included in the QUERI-funded project.

Study Population

We identified all patients with at least one in-person encounter, either inpatient or outpatient, with an OUD diagnosis between October 1, 2016, and June 1, 2018, in three New England VHA medical centers (West Haven, CT; Bedford, MA; and Manchester, NH) and no diagnosis at the same facility in the year prior to the index encounter. We used a 1-year “washout” period to limit the inclusion of veterans with long-standing OUD in our sample and to mirror the time horizon used in the VHA quality metric.4,18 An OUD diagnosis encounter was defined as an encounter with an ICD-10 code of opioid abuse or opioid dependence (F11.1* or F11.2*). We then randomly selected 30 patients from each medical center to create our study sample of 90 patients for chart review. As the rate of misclassification was unknown a priori, this sample size was chosen for feasibility and to mirror similar chart verification studies.25,26,27,28,29,30,31

Chart Review

The electronic medical record for each patient in the study sample was reviewed independently by at least two of three members of the team (BH, SE, DCP). For chart review, we used CAPRI, a readable, non-modifiable version of the VHA electronic medical record which can be used for quality improvement and research purposes.32 Each reviewer evaluated all progress notes, consultation notes, discharge summaries, referrals, and other clinical data within a window of time around the index encounter, defined as 30 days pre- and 90 days post-initial OUD diagnosis encounter date. This window of time was chosen both for feasibility and to allow for inclusion of documentation on behaviors, findings, or clinical decisions informing or reflective of the clinician’s decision-making process. For data extraction, reviewers used a standardized extraction tool in the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) platform.33,34 In addition to assessing the patient’s clinical course, variables of interest included clinic location of index encounter, specialty of the diagnosing clinician, prescription for opioid analgesics or other controlled substances, receipt of MOUD, referral to substance use disorder treatment, and urine toxicology results. These descriptive variables were supplemented by data retrieved from administrative data on the total number of days with an encounter in the year around the index encounter and number of encounters with an OUD diagnosis code in the subsequent year.

Our primary objective was to determine accuracy of OUD diagnoses entered into the medical chart, limited in several important ways. First, we could not perform gold-standard clinical evaluation and, second, clear documentation of DSM-5 OUD criteria met was often lacking. Therefore, we had to make subjective determinations of the likely accuracy of the OUD diagnosis based on the documented clinical course. Following review of the clinical course, each reviewer determined how likely it was the patient met diagnostic criteria for OUD: likely accurate, likely inaccurate, or indeterminate.

Documented clinical decision-making that was consistent with a likely accurate diagnosis of OUD included, but was not limited to, a referral to addiction services, a discussion or initiation of MOUD, or a planned taper or discontinuation of long term opioid therapy (LTOT). Conversely, internally inconsistent actions, such as continued prescription of LTOT without modification to a patient diagnosed with OUD, were assessed as likely inaccurate diagnoses. As a caveat, if these actions were taken for a reason other than a diagnosis of OUD, it did not factor into the determination of accuracy. For example, a patient prescribed extended-release naltrexone for alcohol use disorder would not be consistent with an accurate OUD diagnosis. Patients in the indeterminate category were those with prescribed opioid use but problematic behaviors such as early refills or inappropriate urine toxicology results not meeting DSM-5 criteria, and insufficient other documentation to determine the likelihood of an accurate diagnosis.

We resolved conflicts between reviewers in these determinations via a process in which all the cases with conflicting determinations were discussed and reviewed by the two reviewers of the chart. Following this discussion, a final determination was reached via consensus.

For descriptive purposes, we subsequently reviewed the clinical narratives of patients with likely inaccurate OUD diagnoses and sorted them into two categories: administrative error and clinical error. Administrative errors were those where it appeared as if the diagnosis was both inaccurate and was not intended by the clinician. This included cases where patients were given an OUD diagnosis but with no mention of opioid use (illicit or otherwise) in their clinical record. Clinical errors were those where it appeared the diagnosis was likely inaccurate but was intended by the clinician. For example, this included cases where patients had been prescribed an opioid for analgesia, but with no evidence of problematic behaviors or clinical decisions indicative of clinician concern such as referral to addiction services or taper/discontinuation of LTOT.

We tested inter-rater reliability of initial determinations using the kappa statistic.35 We performed statistical testing via chi-square tests of categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables to determine differences of chart- and administrative data-extracted variables among likely accurate, likely inaccurate, and indeterminate OUD diagnoses. All analyses were performed using Stata/SE version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Two-sided P values < .05 were considered statistically significant a priori.

RESULTS

In the 20-month observation period, we identified 1337 veterans with an incident OUD diagnosis. Within the random sample of 90 veterans used for chart review, 91% were male with a mean age of 49 (SD ± 14.6). (Table 1) On chart review, we found that initial diagnoses were made in a variety of settings, the most common being substance use treatment (26%), mental health treatment (22%), inpatient (12%), primary care (10%), and emergency/urgent care (6%). Within the 120-day window around the index OUD diagnosis encounter, 24% of patients received an opioid analgesic prescription, with the majority of these prescriptions being part of LTOT episodes (23 of 24). In addition, 39% (35 of 90) received or already had a prescription for MOUD of the following types: 21 buprenorphine/naloxone, 6 methadone, and 7 extended-release intramuscular naltrexone. Also, 34% received or already had a prescription for naloxone during the 120-day window around their incident OUD diagnosis.

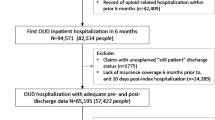

Of the 90 patient records we reviewed, prior to our consensus-generating process, inter-rater reliability was substantial with a kappa of 0.67. After our consensus-generating process, 26 incident OUD diagnoses (29%) were determined to be likely inaccurate (Fig. 1, Table 2). Of these 26 diagnoses, 20 (77%) appeared to be inaccurate diagnoses due to an administrative error and 6 diagnoses 23%) appeared to be due to a clinical error. In addition, in 8 patient records (11%), it was indeterminate whether the diagnosis was accurate due to insufficient documentation. The indeterminate category exclusively contained patients on LTOT for chronic pain who had documented problematic behaviors related to their opioid use (e.g., requests for early refill, inappropriate urine toxicology) but did not have documented behaviors meeting DSM-5 criteria or clinical decision-making consistent with an OUD diagnosis.

We found that diagnoses made in group encounter settings (11%, P < 0.001) and in encounters without direct patient contact such as laboratory medicine encounters (5%, P = 0.006) were associated with likely inaccurate diagnoses. Likely inaccurate or indeterminate diagnoses were also more commonly made in non-mental health clinical encounters (e.g., primary care visit or emergency room visit). Having a diagnosis made in a medical inpatient clinical setting (12%, P = 0.83) was not associated with a likely accurate diagnosis compared to outpatient clinical settings, nor was a diagnosis made by an MD or APRN (60%, P = 0.09) compared to diagnoses made by other clinicians. Having more than one encounter with an OUD diagnosis (P < 0.001) and fewer visits in the VHA in the year of the incident OUD encounter (24.8 visits vs. 53.0 visits, P < 0.001) were associated with likely accurate diagnoses (Table 3).

Clinical decisions and actions, such as prescription of MOUD (P = 0.003), made during the clinical encounter were associated with a likely accurate diagnosis. Receipt of an opioid prescription for pain (whether LTOT or not) was associated with a likely inaccurate or indeterminate OUD diagnosis. (P < 0.001) Older age was associated with a likely inaccurate or indeterminate OUD diagnosis (P < 0.001), with likely accurate diagnoses being more common in younger veterans (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this chart verification study, we assessed a significant proportion of incident OUD diagnoses occurring within three VHA medical centers as likely inaccurate. These likely inaccurate diagnoses reflected errors both due to systems issues and due to clinical decision-making by individual providers. In addition, among a non-negligible proportion of patients, it was indeterminate whether the OUD diagnosis was accurate due insufficient documentation in their medical record.

If the proportion of inaccurate OUD diagnoses in the whole population of individuals receiving care in the VHA is similar to that found in our sample, any decisions based on the reported metric will be fundamentally flawed and may lead to other negative impacts.23,24,36 For example, inaccurate metrics can create inefficiency in the allocation of resources targeting underperforming medical centers. They can also create tension between administrators and frontline clinicians if clinicians are being prompted to change practice based on metrics that do not reflect their clinical judgment. To avoid these negative impacts, improvements in diagnostic accuracy and documentation of OUD are needed.

In addition, inaccurate OUD diagnoses can have consequences for health services research that analyzes flawed administrative data.22,25,37 These errors can lead to systematic bias and erroneous inferences about the population of patients with OUD. For example, many inaccurate or indeterminate OUD diagnoses occurred in patients on LTOT and, if replicated in larger samples, our findings suggest the need for caution in making inferences about the prevalence of OUD in this population based on administrative claims data. Finally, for individual patients, the presence of an inaccurate OUD diagnosis can lead to discrimination, stigma, or barriers to accessing treatment.6

We found a significant number of OUD diagnoses due to errors in clinical reasoning, potentially due to clinician confusion about OUD diagnostic criteria and the application of ICD-10 OUD diagnostic codes. Approximately half of the diagnoses made during one-on-one clinical encounters in non-mental health settings were likely inaccurate or had insufficient documentation. Further research is needed to investigate clinician reasoning when applying OUD diagnostic codes. As noted above, one likely driver of misapplication of OUD diagnostic codes is retention of out-of-date DSM-IV terminology in the ICD-10. In particular, the DSM-IV diagnosis of opioid dependence, which maps to severe OUD in DSM-5, is distinct from physical dependence to opioids and physical dependence, by-it-self, is not sufficient criteria for diagnosis of OUD. Furthermore, in patients on long term opioid therapy (LTOT) for chronic pain, physical dependence is to be expected and cannot be included in an OUD diagnosis per the DSM-5.7 Additionally, patients on LTOT can manifest problematic behaviors related to their opioid use that do not meet criteria for OUD for which there is no other applicable diagnostic code. Change of administrative codes to reflect up-to-date terminology in DSM-5 (i.e., mild/moderate/severe opioid use disorder) is one step to improve conceptualization and application of OUD diagnostic codes.

Also, we found a significant number of medical records that had insufficient information to determine the accuracy of the OUD diagnosis. Very few of the notes attached to the initial OUD diagnosis had clear explication of why the code was applied or what clinical criteria were met. Given this problem, in systems like the VHA with an electronic medical record, the use of templates that clearly lay out DSM-5 criteria tied to initial OUD diagnoses could improve accurate application of OUD diagnostic codes. It is also imperative to improve training on diagnostic criteria for OUD and appropriate documentation of clinical decision making in non-mental health clinical settings given the important role they have in providing MOUD for at-risk veterans.6

The likely inaccurate OUD diagnoses occurred in a variety of clinical and non-clinical settings within the VHA, though a higher proportion of likely inaccurate incident OUD diagnoses occurred in non-clinical and group settings, which do not involve one-on-one encounters with a clinician. These diagnoses likely represent systematic errors in application of OUD diagnostic codes and suggest that health systems should review how OUD diagnostic codes are applied in these settings. The prevalence of this practice in other VHA medical centers should be assessed and corrected where discovered. We also observed that accuracy of OUD diagnostic codes improved if a veteran had more than one encounter with an OUD diagnosis.

The demographic and clinical factors we found to be associated with likely inaccurate OUD diagnosis, which can be derived from administrative data, should be confirmed in subsequent larger analyses. If confirmed, quality metrics or research studies regarding OUD that use administrative data could adopt this criterion to improve reliability of inferences made from this data.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study. First, data collected via direct chart review cannot replace clinical evaluation for OUD. Therefore, it is possible that individuals identified as having a likely inaccurate OUD diagnosis may in fact have met the criteria for OUD, even if not reflected in the clinical record. However, to prevent mis-categorization, our chart review included a 120-day window of all clinical notes and information to capture any clinical decision-making or subsequent evaluation reflective of the diagnosis of OUD that occurred within the VHA. Second, we limited our chart review to data from three VHA medical centers. We could have missed information reflective of an accurate OUD diagnosis captured in medical records at other VHA medical centers or outside of the VHA. Related, our sample size limited the number of female veterans included in our study. It is also unclear if our results would be generalizable to other populations, such as female veterans, other VHA medical centers, or medical centers outside of the VHA. Third, several decisions were made, although in line with previous chart verification studies and the VHA quality metric, to structure our study, such as 1-year washout period and a 120-day window for chart review, that could have biased our study results or missed information in the chart reflective of an accurate OUD diagnosis. Finally, our evaluation of the likelihood of accuracy of OUD diagnoses was based on subjective determination of three chart reviewers. However, all reviewers were trained in addiction medicine and regularly evaluate patients with OUD. To reduce inter-rater discrepancy, all charts were reviewed by at least two reviewers and any disagreement was resolved by consensus.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings of the characteristics and settings of encounters of new diagnoses of OUD associated with insufficient supporting documentation can inform VHA quality metrics. We anticipate this information will lead to potential systems changes that improve the accuracy of OUD diagnoses.

References

Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith H 4th, Davis NL. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2017-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(11):290-297.

Lin LA, Peltzman T, McCarthy JF, Oliva EM, Trafton JA, Bohnert ASB. Changing Trends in Opioid Overdose Deaths and Prescription Opioid Receipt Among Veterans. Am J Prev Med. 2019 Jul;57(1):106-10.

Wu LT, Zhu H, Swartz MS. Treatment utilization among persons with opioid use disorder in the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016 Dec 1;169:117-27.

Wyse JJ, Gordon AJ, Dobscha SK, Morasco BJ, Tiffany E, Drexler K, et al. Medications for opioid use disorder in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system: Historical perspective, lessons learned, and next steps. Subst Abus. 2018;39(2):139-44.

Saitz R. Terminology and Conceptualization of Opioid Use Disorder and Implications for Treatment. In Treating Opioid Addiction. Eds. Kelly JF, Wakeman SE. Springer International Publishing; 2019:79-87.

Donroe JH, Bhatraju EP, Tsui JI, Edelman EJ. Identification and Management of Opioid Use Disorder in Primary Care: an Update. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020 Apr 13;22(5):23.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®): American Psychiatric Pub; 2013.

World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems: 10th revision (ICD-10). Available at: http://www who int/classifications/apps/icd/icd. Accessed August 5, 2020.

Manhapra A, Arias AJ, Ballantyne JC. The conundrum of opioid tapering in long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: A commentary. Subst Abus. 2018;39(2):152-161.

Madras BK. The Surge of Opioid Use, Addiction, and Overdoses: Responsibility and Response of the US Health Care System. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):441-442.

Christie C BC, Cooper R, Kennedy PJ, Madras B, Bondi P. The president’s commission on combating drug addiction and the opioid crisis. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2017.

Manhapra A, Stefanovics E, Rosenheck R. Initiating opioid agonist treatment for opioid use disorder nationally in the Veterans Health Administration: Who gets what? Subst Abus. 2020;41(1):110-20.

Crane D, Marcotte M, Applegate M, Massatti R, Hurst M, Menegay M, et al. A statewide quality improvement (QI) initiative for better health outcomes and family stability among pregnant women with opioid use disorder (OUD) and their infants. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019 Jul;102:53-9.

Thomas CP, Ritter GA, Harris AHS, Garnick DW, Freedman KI, Herbert B. Applying American Society of Addiction Medicine Performance Measures in Commercial Health Insurance and Services Data. J Addict Med. 2018 Jul/Aug;12(4):287-94.

Thompson HM, Hill K, Jadhav R, Webb TA, Pollack M, Karnik N. The Substance Use Intervention Team: A Preliminary Analysis of a Population-level Strategy to Address the Opioid Crisis at an Academic Health Center. J Addict Med. 2019 Nov/Dec;13(6):460-3.

Veterans Health Administration. Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL). Available at: https://www.va.gov/QUALITYOFCARE/measure-up/Strategic_Analytics_for_Improvement_and_Learning_SAIL.asp. Accessed on August 5, 2020.

Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, Martins S, Lewis ET, Paik M, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration's Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017 Feb;14(1):34-49.

Veterans Health Administration. SUD16: Electronic Technical Manual (eTM) Measure Specification. Available at: http://vaww.car.rtp.med.va.gov/programs/pm/pmETechMan.aspx Accessed on July 9, 2020.

SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act: The Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities Act, United States Congress, 115th Congress (2017-2018) Sess.

O'Malley KJ, Cook KF, Price MD, Wildes KR, Hurdle JF, Ashton CM. Measuring diagnoses: ICD code accuracy. Health Serv Res. 2005 Oct;40(5 Pt 2):1620-39.

Chubak J, Pocobelli G, Weiss NS. Tradeoffs between accuracy measures for electronic health care data algorithms. J Clin Epidemiol. 2012 Mar;65(3):343-9.e2.

Feder SL. Data Quality in Electronic Health Records Research: Quality Domains and Assessment Methods. West J Nurs Res. 2018 May;40(5):753-66.

Prentice JC, Frakt AB, Pizer SD. Metrics That Matter. J Gen Intern Med.. 2016 Apr;31 Suppl 1:70-3.

Blumenthal D, McGinnis JM. Measuring Vital Signs: an IOM report on core metrics for health and health care progress. JAMA. 2015 May 19;313(19):1901-2.

Peabody JW, Luck J, Jain S, Bertenthal D, Glassman P. Assessing the accuracy of administrative data in health information systems. Med Care. 2004 Nov;42(11):1066-72.

Feder SL, Redeker NS, Jeon S, Schulman-Green D, Womack JA, Tate JP, et al. Validation of the ICD-9 Diagnostic Code for Palliative Care in Patients Hospitalized With Heart Failure Within the Veterans Health Administration. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018 Jul;35(7):959-65.

Cooke CR, Joo MJ, Anderson SM, Lee TA, Udris EM, Johnson E, et al. The validity of using ICD-9 codes and pharmacy records to identify patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011 Feb 16;11:37.

Bullano MF, Kamat S, Willey VJ, Barlas S, Watson DJ, Brenneman SK. Agreement between administrative claims and the medical record in identifying patients with a diagnosis of hypertension. Med Care. 2006 May;44(5):486-90.

Maalouf FI, Cooper WO, Stratton SM, et al. Positive Predictive Value of Administrative Data for Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome. Pediatrics. 2019;143(1):e20174183.

Assimon MM, Nguyen T, Katsanos SL, Brunelli SM, Flythe JE. Identification of volume overload hospitalizations among hemodialysis patients using administrative claims: a validation study. BMC Nephrol. 2016 Nov 11;17(1):173.

Gershon AS, Wang C, Guan J, Vasilevska-Ristovska J, Cicutto L, To T. Identifying individuals with physcian diagnosed COPD in health administrative databases. COPD. 2009;6(5):388-394.

Veterans Health Administration. Compensation and Pension Records Interchange(CAPRI). Available at: https://www.va.gov/vdl/documents/Financial_Admin/CAPRI/DVBA_27_209_RN.pdf Accessed on August 4, 2020.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O'Neal L, et al. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019 Jul;95:103208.

Veterans Health Administration. VA Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap). Available at: https://www.virec.research.va.gov/Resources/REDCap.asp. Accessed on April 20, 2020.

McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2012;22(3):276-282.

McGinnis JM, Malphrus E, Blumenthal D. Vital signs: core metrics for health and health care progress. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015.

Ladouceur M, Rahme E, Pineau CA, Joseph L. Robustness of prevalence estimates derived from misclassified data from administrative databases. Biometrics. 2007;63(1):272-279.

Funding

Funding for this work was provided through a VA QUERI grant (QUE PII 18-180) titled Facilitated Implementation of Stepped Care for Opioid Use Disorder. Dr. Howell receives funding from the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations through the National Clinician Scholars Program and grant number 5K12DA033312 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Earlier versions of this work were presented as an oral presentation at the 2019 VA HSR&D/QUERI National Conference in Washington, DC, and as a poster at the AMERSA Annual Conference in Boston, MA.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Howell, B.A., Abel, E.A., Park, D. et al. Validity of Incident Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) Diagnoses in Administrative Data: a Chart Verification Study. J GEN INTERN MED 36, 1264–1270 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06339-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06339-3