ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Family and caregiver interventions typically aim to develop family members’ coping and caregiving skills and to reduce caregiver burden. We conducted a systematic review of published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating whether family-involved interventions improve patient outcomes among adults with cancer.

METHODS

RCTs enrolling patients with cancer were identified by searching MEDLINE, PsycInfo and other sources through December 2012. Studies were limited to subjects over 18 years of age, published in English language, and conducted in the United States. Patient outcomes included global quality of life; physical, general psychological and social functioning; depression/anxiety; symptom control and management; health care utilization; and relationship adjustment.

RESULTS

We identified 27 unique trials, of which 18 compared a family intervention to usual care or wait list (i.e., usual care with promise of intervention at completion of study period) and 13 compared one family intervention to another individual or family intervention (active control). Compared to usual care, overall strength of evidence for family interventions was low. The available data indicated that overall, family-involved interventions did not consistently improve outcomes of interest. Similarly, with low or insufficient evidence, family-involved interventions were not superior to active controls at improving cancer patient outcomes.

DISCUSSION

Overall, there was low or insufficient evidence that family and caregiver interventions were superior to usual or active care. Variability in study populations and interventions made pooling of data problematic and generalizing findings from any single study difficult. Most of the included trials were of poor or fair quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

BACKGROUND

In the United States, nearly 14 million people, or one in 23, are now cancer survivors. Only 3 million people, or one in 69, were cancer survivors in 1971.1 Family and caregiver interventions, especially those targeted to families caring for someone with a physical health condition, including the large number living after a cancer diagnosis, typically aim to develop family member skills and reduce their burden. Reflecting this, the majority of intervention studies targeting families and reviews of these studies have concentrated only on family member outcomes.2–5

An often implicit assumption is that by reducing family member burden and improving their skills, the patient will also benefit. We conducted a systematic review of interventions that involved family members, but concentrated on how these interventions affect patient outcomes.

Based on an expanded evidence review available online,6 we addressed the following questions: 1) What are the benefits of family and caregiver psychosocial interventions on outcomes for adults with cancer compared to usual care or wait list? (i.e., efficacy of interventions); and 2) What are the benefits of one family or caregiver-involved psychosocial intervention compared to either a patient intervention or another alternative family-oriented intervention (active controls) in improving outcomes for adults with cancer? (i.e., specificity or comparative effectiveness of interventions). The key questions and scope were refined with input from a technical expert panel (TEP), a panel made up of clinicians, caregiving researchers and administrators.

METHODS

Data Sources

We searched MEDLINE (Ovid) and PsycINFO for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and systematic reviews published from 1996 to December 2012, using the following search terms: family, couples, caregivers, home nursing, legal guardians, couple therapy, family therapy, or marital therapy (Online Appendix Figure 1). Because family support can vary by social, cultural and clinical norms and health care resources and policies,7,8 this review, which is intended for use in the U.S., is limited to studies conducted in the U.S. We included RCTs involving subjects over 18 years of age and published in the English language. Additional citations were identified from reference lists of retrieved articles and by suggestions from TEP members.

Definitions of Key Concepts of Family and Outcomes

We used the term “family” to describe all those, related and non-related, who provide direct care and support to people with cancer. Although study settings often determine how the person with cancer was described (e.g., patient, resident, spouse), for our purposes we use the word “patient” to describe the person with cancer.

We examined the effect of family-involved interventions on five patient outcomes: quality of life, depression/anxiety, symptom control, health care utilization, and relationship adjustment. We included global quality of life and physical, general psychological and social functioning in our definition of quality of life, and included data only from validated assessments of these constructs. For depression/anxiety outcomes, we included reports of depressive symptoms or anxiety using standardized assessments. For symptom control or management outcomes, we included reports of any physical symptoms associated with treatment or disease progression (pain, sexual functioning, and side effect assessment). Utilization outcomes included all types of health care utilization, including hospitalization, or emergency room visits, and relationship adjustment included family functioning and relationship quality.

Categorization of Interventions

We created categories of interventions based on common characteristics across trials. Each trial was grouped into one of five intervention categories: 1) telephone or web-based counseling, where, in at least one intervention arm, telephone or web-based counseling was provided separately for family members and patient; 2) behavioral couples therapy or adaptations of cognitive behavior therapy for couples; 3) training for family members to manage or control patient symptoms; 4) training for family members to manage or control patient symptoms or behaviors, plus family support or counseling; and 5) unique interventions that could not be adequately captured by the above categories.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Titles, abstracts, and articles were reviewed by study authors. Study characteristics, patient characteristics, and outcomes data from trials that met inclusion criteria were extracted once by one author and then verified by another, all under the supervision of the Principal Investigator (JG). Only outcomes that were assessed using previously published scales or measures or had clear end-points (e.g., death, hospitalization) were included. In order to determine both immediate and long-term benefits of the intervention, we captured, whenever possible, data at two time-points: post-intervention and any point 6 months or more post-intervention. For studies with multiple assessments at greater than 6 months post-intervention, data from the last available assessment was extracted.

Evaluation of risk of bias was adapted from criteria used by Cochrane Collaboration.9 We assessed the risk of bias for each trial and used this assessment as the basis for rating the trial’s quality. We rated a trial “good quality” (low risk of bias) when authors indicated adequate allocation concealment, a minimum of single blinding (investigators or assessors are blinded), and that either intent-to-treat analysis was conducted or an adequate description for dropouts/attrition by group was provided. We rated trials “fair quality” (moderate risk of bias) when allocation concealment and blinding criteria were either met or unclear (i.e., the paper makes no mention of allocation concealment or blinding) and no more than one of the remaining criterion (intention-to-treat analysis, withdrawals and dropouts by group assignment were adequately described) was unmet. A trial with adequate allocation concealment that did not meet other domains, or did not make clear whether other domains were met, was rated as fair. We rated trials “poor quality” (high risk of bias) if the trial had inadequate allocation concealment or no blinding and/or it clearly met a maximum of one of the established risk-of-bias domains.

We evaluated strength of evidence for each outcome based on criteria used by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.10 Strength of evidence was rated using the following grades: 1) high confidence—further research is unlikely to change the confidence in the estimate of effect, meaning that the evidence reflects the true effect; 2) moderate confidence—further research may change our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate; 3) low confidence—further research is likely to have an important impact on the confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate, meaning that there is low confidence that the evidence reflects the true effect; and 4) insufficient—the evidence was unavailable or did not permit a conclusion.

Data Synthesis

We analyzed studies by comparing their characteristics, methods, and findings. When reported, intervention effect sizes from trials were extracted. If a trial’s effect sizes were not reported, but adequate data were provided, we calculated intervention effect sizes using Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.2 software.11 The effect sizes were interpreted based on Cohen’s definition of small (0.2), medium (0.5), and large (0.8) effect sizes.12

RESULTS

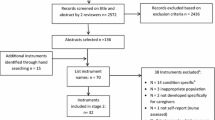

The identification and selection process for papers can be found online in Appendix Figure 2. From 2,771 papers, we identified 29 papers representing 27 unique trials that met our inclusion criteria. Details on study characteristics, interventions, comparators and outcomes assessed can be found online in Appendix Table 1, or accessed in the expanded evidence report.6

Description of Studies

Baseline characteristics for patients and family members are found in Table 1. Overall, the study populations and interventions were heterogeneous, varying in family member characteristics, type of intervention, and comparators. Although 12 trials included only patients with early-stage to mid-stage cancers and five included only those with late-stage cancers, nearly equal numbers of patients in these trials (early-stage to mid-stage, n = 1242; late-stage, n = 1158) were analyzed. Nearly all (n = 23) reported using a specific manual or protocol for the intervention.

What are the Benefits of Family and Caregiver Psychosocial Interventions for Adults with Cancer Compared to Usual Care or Wait List?

We identified 18 cancer trials,13–32 with all but one28 comparing family-involved interventions to usual care (n = 17). Most studies were of fair quality (n = 15) and three were rated as poor quality (Table 2). Trials enrolled either men with prostate cancer (n = 6), women with breast cancer (n = 5), or either men or women with any type of cancer (n = 7) (Table 2). Studies ranged in size from 14 to 476 participants and included an average of six sessions per intervention (range: 3–10 sessions). Six trials included follow-up periods of 6-8 months after the completion of the intervention,13–15,23–25,29 and one followed participants 12 months post-intervention.28

Overall Benefits

We found 13 of 18 trials with no significant differences between usual care and family-involved interventions, and five reporting superior benefits from interventions on at least one outcome of interest (Table 2). Trials with significant effects included patients at all stages of disease. Effect sizes were typically small to moderate (online Appendix Table 2). No trials indicated that the comparator, usual care, was superior to family-involved interventions on outcomes. None of the studies reported on health care utilization. The overall strength of evidence for intervention effectiveness was low for all outcomes (Table 3), due to moderate risk of bias, imprecision of the effect size and poor methodological quality. Sample sizes were small and post-intervention data comparing outcomes data between conditions were not consistently reported. The variability in study populations and interventions made pooling of data problematic and drawing broader conclusions across the literature difficult.

We found limited reporting of outcomes within each intervention category. This precluded us from calculating more reliable estimates to determine the strength of evidence of each intervention on particular outcomes. A summary of study findings by intervention category can be found online in Appendix Table 3. Across intervention types, interventions comparing usual care to only one family member, instead of the family member-patient dyad, appeared more effective, especially for managing or controlling patient treatment symptoms and reducing patient depression/anxiety. The exception was couples who reported difficulties in their relationships or were in relatively new relationships. One trial, for example, found that couple therapy was more effective than usual care in improving quality of life at 6 months post-intervention for patients whose partners were the least supportive at the trial’s onset.13 Another found that, compared to usual care, a couples’ intervention was only beneficial at improving quality of life for a sub-group of couples in shorter-term relationships.24

For other patient-only outcomes, however, either no trials or only a single trial reported significant improvements between intervention and usual care conditions. One trial showed some promise compared to usual care, with significant differences in multiple outcomes (patient physical and social functioning and depression) following the intervention.31 Trials like this, however, were the exception. Family-involved interventions were superior to usual care/wait list in patient symptom management and depression in few trials, and overall, there was insufficient evidence that these intervention strategies affected other patient outcomes.

What are the Benefits of One Family or Caregiver-Involved Psychosocial Intervention Compared to Either: 1) A Patient-Directed Intervention or 2) Another Alternative Family-Oriented Intervention in Improving Outcomes for Adults With Cancer?

Thirteen trials met inclusion criteria,16,22,28,32–42 including four that also had usual care16,22,32 or wait list28 arms. Most interventions were compared to other family treatments (n = 11), typically health education or psychoeducation for families. Three trials, however, compared family-involved interventions to individual treatments.16,28,37 One of these compared usual care to two intervention arms, one targeted to the patient-family member dyad and the other only to the patient.28

Trials were mostly of fair quality (n = 9). Two each were rated good and poor (Tables 4). Studies ranged in size from 12 to 249, with a median 122 patient-family member dyads per trial. Trials included patients with any kind of cancer (n = 4), prostate (n = 4), breast (n = 2), gastrointestinal (n = 1) or lung (n = 2) cancers (Table 4). Half the patients were men (51 %) and most were married. More than half of the family members were women.

Overall Benefits

More than half the trials assessed general psychological functioning (seven of 13) and symptom control/management (ten of 13), but only three trials for each outcome reported significant findings (see Table 4). Trials with significant effects included patients at all stages of disease. As shown in Table 5, the overall strength of evidence for the superiority of family-involved interventions compared to active controls was low for these outcomes due to the moderate risk of bias, imprecision of the effect size, and poor methodological quality, including small sample sizes. Fewer trials assessed other outcomes. Two of five interventions were superior to comparators on post-intervention depression/anxiety and one of three interventions on post-intervention relationship adjustment. For physical functioning, social functioning, and global quality of life, we found insufficient evidence due to few trials reporting these outcomes and inadequate reporting of outcomes between conditions post-intervention. There were no data on health care utilization, including hospitalizations. The variability in study populations and interventions prevented pooling of data and made generalizing findings from any single study difficult.

A summary of study findings by intervention category can be found online in Appendix Table 3. Of the three trials that compared individual treatment to family or couple treatment, interventions were equally effective at improving outcomes at post-intervention.16,28,37 One trial showed that, compared to a patient-only intervention, the family-involved intervention demonstrated better post-treatment psychological functioning and symptom control at 6 months, but not immediately post-intervention.28

Results from trials that directly compared different family-involved interventions suggested that some family-involved interventions may be superior to others on specific patient outcomes, especially symptom control/management and depression/anxiety, but not for other outcomes, such as physical or social functioning, or global quality of life. Of the two good quality trials that compared family-involved interventions, one compared a couples’ education and support group to a couples’ treatment group that taught caregivers to “coach” lung cancer patients in coping skills. The interventions showed no differences in patients’ physical or social functioning, depression/anxiety or symptom control/management.39 The other trial compared an education and support group for couples to partner-assisted emotional disclosure therapy,40 and showed no improvement in general psychological functioning, but significant improvement in relationship adjustment. Another trial showed an unanticipated effect, with the health education only intervention significantly improving general psychological functioning, depression, and symptom control compared to telephone counseling for families.34

DISCUSSION

Family-involved interventions in the U.S. did not consistently lead to better outcomes for patients with cancer. The evidence indicated that family interventions were neither superior to usual care nor to active controls such as education, or any alternative interventions, such as patient-only interventions.

Evidence from single trials favored family-involved interventions over usual cancer care for improving depression/anxiety, general psychological functioning, relationship adjustment, and patient symptoms, such as side effects from treatment, and depression/anxiety, although we did not find strong evidence for improvements in quality of life or relationship adjustment.

Evidence, albeit weak, suggested that some family-involved interventions were superior for improving symptoms, such as pain and symptom distress compared to interventions that were targeted to patients only or interventions that provided only health education. Family-involved interventions designed for specific sub-groups (e.g., highly distressed patients, patients with early-stage cancer, couples in newer relationships) may be more effective at improving the management of a broad range of cancer and treatment-related symptoms and depression/anxiety than usual care. Likewise, those that teach families a specific skill (e.g., reflexology) to address a symptom or problem (e.g., pain) may be more effective for improving patient symptoms than providing families and patients general support or education. However, we emphasize caution about the broader applicability of any intervention benefits, because of the potential that benefits may be due to chance. All but two of the 27 trials were of poor or fair quality, and although a broad range of symptoms (e.g., sexual functioning, side effect severity, symptom-related distress) improved within a single trial, we found little evidence across trials to suggest that specific symptoms commonly associated with cancer and cancer treatment, such as pain, fatigue, or nausea, were more effectively addressed by a family-involved intervention.

We are not aware of other systematic reviews that examine family interventions on cancer patient outcomes. Other comparable reviews43,44 include cancer as only one of multiple physical conditions and do not include comparative effectiveness studies. Unlike previous reviews, we were able to leverage the growing number of published studies to group interventions into categories that provide useful information for researchers and providers about the interventions types being developed and the evidence for each category.

In spite of these differences, our overall findings concur with previous reviews.43,44 Martire et al. reported that family interventions led to better patient outcomes on depression versus comparators, but family interventions were not superior to comparators on patient’s anxiety or physical disability.43 Our review, conducted 10 years after this review, suggests that, despite the increasingly large number of cancer survivors and the important role families are taking in cancer patients’ care, limited progress has been made in the U.S. at improving patient outcomes other than depression or psychological functioning through interventions that involve family. Hartmann’s more recent review also drew similar conclusions to ours. Compared to usual care, family-involved interventions had small but significant improvements on cancer patients’ mental health (e.g., depression/anxiety, quality of life and general mental health), although given the suboptimal methodological rigor of the trials included in the review, the conclusions were tempered.44

It is possible that if we included lower level evidence from observational evidence, in addition to RCTs, we would have different conclusions. Including RCTs conducted in other countries may also have led to different results, although their generalizability to the U.S. may have been limited. A number of studies in our review were also primarily designed to improve family member outcomes (e.g., reducing family member’s burden), not patient outcomes, and this may have affected what outcomes were reported. One would expect interventions not designed to directly benefit patients to naturally lead to fewer patient gains than intervention directly designed to benefit patients. It is possible that interventions effectively targeting family outcomes may subsequently benefit patients, but the effect on family outcomes is insufficiently potent to translate into demonstrated gains in patient outcomes.

Based on our findings, we have a number of recommendations. Our primary recommendation is to improve the methodological rigor of research to reduce bias and improve the overall confidence in the evidence available. To that end, researchers should attend to issues of study quality, including blinding, allocation concealment, descriptions of dropouts, and intent to treat analyses. Outcome data should be reported post-treatment for each condition for direct group comparison, and when feasible, longer-term outcomes should be included to assess the stability of an intervention’s effects. Additionally, researchers should report outcomes according to study subgroups, including relationship of family member to patient, quality of this relationship, and disease stage. Researchers should consider either reducing the number of comparisons or conditions to avoid chance findings, or increase study sample size in order to detect important differences across active comparators. Replication of interventions is a critical next step, especially for higher-quality trials that show significant effects across outcomes, but because family-involved interventions do require a commitment of time and money, their potential benefits, especially if they are marginally effective, need to be considered in relation to their costs.

General interventions for families may not lead to better patient outcomes, but drawing from the limited data we have, family interventions targeting patients with specific cancers, illness stages, related behaviors, or problems associated with the cancer or its treatment may be more effective than usual care or health education only. Likewise, interventions that target highly distressed patients, family members, or couples may have the greatest potential for improvement.

Other studies have shown that family interventions can reduce family members’ perceptions of the burden of providing care.4 However, it remains unclear if by reducing family burden, families can provide better care, which, in turn, then improves patient outcomes. Future research is needed to rigorously test this question. Understanding the link between family and patient health is critical for understanding whether separate interventions should address family and patient issues, or if investing in family interventions will provide downstream improvements in patient outcomes.

Future research should identify sub-groups (e.g., age, sex, disease stage or severity, relationship between patient and family member, quality of the family member-patient relationship, etc.), and these groups, along with cancer type, should be examined to verify if tailoring interventions is more advantageous than a one-size-fits-all intervention. Larger trials adequately powered to analyze sub-groups would provide important data for making decisions about whether and which interventions to implement, to whom and when in the disease course. Collecting long-term outcomes that account for changes in treatment, disease progression and symptom burden between intervention and control groups in these trials could also establish the lasting impact of interventions within sub-groups.

Although the evidence is inconclusive about whether telephone or web-based counseling or other supportive programs that rely on technology are as effective as other forms of counseling, they have potential advantages to rural or home-bound family and patients, low-income families, and families who have internet access, but little access to other resources or community support.

In conclusion, we found sparse and weak evidence to suggest that general family interventions are superior to wait list, treatment as usual, or active alternative interventions for patients with cancers; sub-groups of family members and patients with specific needs may benefit more than others from family interventions. Customizing and targeting family-involved interventions to specific sub-groups may be the most efficient way to improve patient outcomes through family treatment and requires future research.

REFERENCES

American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Progress Report 2013. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(Supplement 1):S1–86.

Thompson CA, Spilsbury K, Hall J, Birks Y, Barnes C, Adamson J. Systematic review of information and support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7:18.

Goy E, Kansagara D, Freeman M. A systematic evidence review ofinterventions for non-professional caregivers of individuals with dementia. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs; 2010 October. Accessed March 12, 2014. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK49194/.

Sorensen S, Pinquart M, Duberstein P. How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2002;42:356–72.

Visser-Meily A, van Heugten C, Post M, Schepers V, Lindeman E. Intervention studies for caregivers of stroke survivors: a critical review. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56:257–67.

Griffin JM, Meis L, Greer N, Jensen A, MacDonald R, Rutks I, et al. Effectiveness of Family Caregiver Interventions on Patient Outcomes among Adults with Cancer or Memory-Related Disorders: A Systematic Review. VA-ESP Project #09-009; 2013.

Torti FM Jr, Gwyther LP, Reed SD, Friedman JY, Schulman KA. A multinational review of recent trends and reports in dementia caregiver burden. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2004;18:99–109.

Corbett A, Stevens J, Aarsland D, et al. Systematic review of services providing information and/or advice to people with dementia and/or their caregivers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27:628–36.

Higgins JPT, Green S, eds. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Accessed March 12, 2014. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org.

Owens DK, Lohr KN, Atkins D, Treadwell JR, Reston JT, Bass EB, et al. AHRQ series paper 5: grading the strength of a body of evidence when comparing medical interventions—Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Effective Health-Care Program. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:513–23.

Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.2. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012.

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988.

Manne SL, Ostroff JS, Winkel G, et al. Couple-focused group intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:634–46.

Giesler RB, Given B, Given CW, et al. Improving the quality of life of patients with prostate carcinoma: a randomized trial testing the efficacy of a nurse-driven intervention. Cancer. 2005;104:752–62.

Northouse LL, Mood DW, Schafenacker A, et al. Randomized clinical trial of a family intervention for prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer. 2007;110:2809–18.

Mishel MH, Belyea M, Germino BB, et al. Helping patients with localized prostate carcinoma manage uncertainty and treatment side effects: nurse-delivered psychoeducational intervention over the telephone. Cancer. 2002;94:1854–66.

Campbell LC, Keefe FJ, McKee DC, et al. Prostate cancer in African Americans: relationship of patient and partner self-efficacy to quality of life. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2004;28:433–44.

Campbell LC, Keefe FJ, Scipio C, et al. Facilitating research participation and improving quality of life for African American prostate cancer survivors and their intimate partners. A pilot study of telephone-based coping skills training. Cancer. 2007;109(2 Suppl):414–24.

Manne SL, Kissane DW, Nelson CJ, Mulhall JP, Winkel G, Zaider T. Intimacy-enhancing psychological intervention for men diagnosed with prostate cancer and their partners: a pilot study. J Sex Med. 2011;8:1197–209.

McCorkle R, Siefert ML, Dowd MFE, Robinson JP, Pickett M. Effects of advanced practice nursing on patient and spouse depressive symptoms, sexual function, and marital interaction after radical prostatectomy. Urol Nurs. 2007;27:65–77.

Northouse L, Kershaw T, Mood D, Schafenacker A. Effects of a family intervention on the quality of life of women with recurrent breast cancer and their family caregivers. Psycho-Oncology. 2005;14:478–91.

Budin WC, Hoskins CN, Haber J, et al. Breast cancer: Education, counseling, and adjustment among patients and partners: A randomized clinical trial. Nurs Res. 2008;57:199–213.

Baucom DH, Porter LS, Kirby JS, et al. A couple-based intervention for female breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18:276–83.

Kayser K, Feldman BN, Borstelmann NA, Daniels AA. Effects of a randomized couple-based intervention on quality of life of breast cancer patients and their partners. Soc Work Res. 2010;34:20–32.

Manne S, Ostroff JS, Winkel G. Social-cognitive processes as moderators of a couple-focused group intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2007;26:735–44.

Keefe FJ, Ahles TA, Sutton L, et al. Partner-guided cancer pain management at the end of life: a preliminary study. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2005;29:263–72.

Kozachik SL, Given CW, Given BA, et al. Improving depressive symptoms among caregivers of patients with cancer: results of a randomized clinical trial. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2001;28:1149–57.

Nezu AM, Nezu CM, Felgoise SH, McClure KS, Houts PS. Project Genesis: assessing the efficacy of problem-solving therapy for distressed adult cancer patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:1036–48.

Blanchard CG, Toseland RW, McCallion P. The effects of a problem-solving intervention with spouses of cancer patients. J Psychosoc Oncol. 1996;14:1–21.

Meyers FJ, Carducci M, Loscalzo MJ, Linder J, Greasby T, Beckett LA. Effects of a problem-solving intervention (COPE) on quality of life for patients with advanced cancer on clinical trials and their caregivers: Simultaneous care educational intervention (SCEI): Linking palliation and clinical trials. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:465–73.

Kurtz ME, Kurtz J, Given CW, Given B. A randomized, controlled trial of a patient/caregiver symptom control intervention: Effects on depressive symptomatology of caregivers of cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2005;30:112–22.

McMillan SC, Small BJ. Using the COPE intervention for family caregivers to improve symptoms of hospice homecare patients: a clinical trial. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:313–21.

Badger T, Segrin C, Dorros SM, Meek P, Lopez AM. Depression and anxiety in women with breast cancer and their partners. Nurs Res. 2007;56:44–53.

Badger TA, Segrin C, Figueredo AJ, et al. Psychosocial interventions to improve quality of life in prostate cancer survivors and their intimate or family partners. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:833–44.

Schover LR, Canada AL, Yuan Y, et al. A randomized trial of internet-based versus traditional sexual counseling for couples after localized prostate cancer treatment. Cancer. 2012;118:500–9.

Given B, Given CW, Sikorskii A, Jeon S, Sherwood P, Rahbar M. The impact of providing symptom management assistance on caregiver reaction: Results of a randomized trial. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2006;32:433–43.

Canada AL, Neese LE, Sui D, Schover LR. Pilot intervention to enhance sexual rehabilitation for couples after treatment for localized prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:2689–700.

Gustafson DH, DuBenske LL, Namkoong K, et al. An eHealth system supporting palliative care for patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer: A randomized trial. Cancer. 2013;119:1744–51.

Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Garst J, et al. Caregiver-assisted coping skills training for lung cancer: Results of a randomized clinical trial. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2011;41:1–13.

Porter LS, Keefe FJ, Baucom DH, et al. Partner-assisted emotional disclosure for patients with gastrointestinal cancer: results from a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2009;115(18 Suppl):4326–38.

Mokuau N, Braun KL, Wong LK, Higuchi P, Gotay CC. Development of a family intervention for Native Hawaiian women with cancer: a pilot study. Soc Work. 2008;53:9–19.

Stephenson NLN, Swanson M, Dalton J, Keefe FJ, Engelke M. Partner-delivered reflexology: effects on cancer pain and anxiety. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007;34:127–32.

Martire LM, Lustig AP, Schulz R, Miller GE, Helgeson VS. Is it beneficial to involve a family member? A meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for chronic illness. Health Psychol. 2004;23:599–611.

Hartmann M, Bazner E, Wild B, Eisler I, Herzog W. Effects of interventions involving the family in the treatment of adult patients with chronic physical diseases: a meta-analysis. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79:136–48.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI). The findings and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or QUERI. The sponsor was not involved in any aspect of the study’s design and conduct; data collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

The authors thank members of the Technical Expert Panel who provided consultation on this review.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest. None of the authors has a direct interest in the results of the research. Publication will not confer a benefit on them or on any organization with which they are associated.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Griffin, J.M., Meis, L.A., MacDonald, R. et al. Effectiveness of Family and Caregiver Interventions on Patient Outcomes in Adults with Cancer: A Systematic Review. J GEN INTERN MED 29, 1274–1282 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2873-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2873-2