ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVES

The current review examines the effectiveness of simulation-based medical education (SBME) for training health professionals in cardiac physical examination and examines the relative effectiveness of key instructional design features.

METHODS

Data sources included a comprehensive, systematic search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsychINFO, ERIC, Web of Science, and Scopus through May 2011. Included studies investigated SBME to teach health profession learners cardiac physical examination skills using outcomes of knowledge or skill. We carried out duplicate assessment of study quality and data abstraction and pooled effect sizes using random effects.

RESULTS

We identified 18 articles for inclusion. Thirteen compared SBME to no-intervention (either single group pre-post comparisons or SBME added to other instruction common to all learners, such as traditional bedside teaching), three compared SBME to other educational interventions, and two compared two SBME interventions. Meta-analysis of the 13 no-intervention comparison studies demonstrated that simulation-based instruction in cardiac auscultation was effective, with pooled effect sizes of 1.10 (95 % CI 0.49–1.72; p < 0.001; I2 = 92.4 %) for knowledge outcomes and 0.87 (95 % CI 0.52–1.22; p < 0.001; I2 = 91.5 %) for skills. In sub-group analysis, hands-on practice with the simulator appeared to be an important teaching technique. Narrative review of the comparative effectiveness studies suggests that SBME may be of similar effectiveness to other active educational interventions, but more studies are required.

LIMITATIONS

The quantity of published evidence and the relative lack of comparative effectiveness studies limit this review.

CONCLUSIONS

SBME is an effective educational strategy for teaching cardiac auscultation. Future studies should focus on comparing key instructional design features and establishing SBME’s relative effectiveness compared to other educational interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Competence in physical examination of the cardiovascular system is a key clinical skill. Clinicians use the cardiovascular physical exam as a non-invasive tool to directly diagnose and assess severity of disease and guide further evaluation.1 However, multiple studies have documented the weak cardiac physical examination skills of trainees and clinicians.2,3

The optimal approach to teaching cardiac physical examination remains unknown. To become competent in cardiac physical examination, a clinician must examine patients with a wide variety of cardiac conditions and have encountered such diagnoses on a repetitive basis.4 The availability and accessibility of patients with cardiac pathology constitute barriers to the acquisition of cardiac physical exam skills. Rare but important pathology presents infrequently in clinical encounters. In academic centers, trainees must often compete to examine an ever-dwindling number of suitable patients.

Although many of these obstacles are not unique to the teaching of the cardiovascular physical exam, cardiology has led the way in developing alternative teaching formats to overcome these limitations, including recorded audio files, multimedia CD-ROMs, and mannequin-based cardiopulmonary simulators (CPS). Simulation-based medical education (SBME) physically engages the learner in educational experiences that mimic a real patient encounter,5 as in the learning experience provided by the CPS. Medical schools frequently use simulation to teach physical diagnosis, with a reported prevalence of 84–94 % from first to fourth year among medical schools responding to a 2010 AAMC survey.6 Conceptually, SBME has great potential as a tool to enhance the education of trainees’ physical examination skills by facilitating repetitive and deliberately planned exposure to key auscultatory abnormalities without the constraints of patient and pathology availability, and by providing an environment in which questions and errors can be discussed without negative clinical consequences.4 By embedding the cardiac findings within a mannequin, SBME could improve the transfer of clinical skills from the teaching setting to real patients.

Despite these potential advantages, the relative benefit of SBME compared to other instructional modalities for cardiac physical examination training remains unclear, and the issue of how best to use SBME in this context is unresolved. Many individual studies have evaluated educational modalities for teaching cardiac auscultation skills, and a comprehensive synthesis of this evidence would help educators and clinicians use these tools effectively. We could not identify a systematic review synthesizing the evidence for any of these modalities. Rather, reviews to this point have focused on SBME generally, including two recent reviews showing that SBME is effective across multiple educational domains compared to no educational intervention or in addition to traditional clinical education.5,7 To address this gap, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature.

METHODS

The general methods for this systematic review have been published previously and are presented here in abbreviated format.7 This review was planned, conducted, and reported in adherence to PRISMA standards of quality for reporting meta-analyses.8 IRB approval was not required.

Questions

We sought to examine (1) the effectiveness of SBME for training health professionals in cardiac physical examination skills and (2) the instructional design features that enhance the effectiveness of SBME for teaching cardiac auscultation. We defined SBME as an educational tool or device with which the learner physically interacts to mimic an aspect of clinical care. We excluded studies that evaluated only audio-recordings, CD-ROMS, computer-based virtual patients, phonocardiosimulators, or standardized patients.

Study Eligibility

We included studies published in any language that investigated the use of SBME to teach health profession learners cardiac physical examination skills at any stage in training or practice using outcomes of learning, behaviors with patients in clinical practice, or patient outcomes. We included single-group pretest-posttest studies, two-group randomized and nonrandomized studies, and studies in which simulation was added to other instruction common to all learners, such as a traditional clerkship rotation, bedside teaching session, or classroom instruction.

Study Identification

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsychINFO, ERIC, Web of Science, and Scopus using search terms designated by an experienced research librarian, focused on the intervention (e.g., simulator, simulation, manikin, Harvey), topic (e.g., physical examination skills), and learners (e.g., education medical, education nursing, education professional, student health occupations, internship, and residency). No beginning date was used, and the last date of the search was May 11, 2011. We searched for additional studies in the reference lists of all included articles.7

Study Selection

We screened all titles and abstracts independently and in duplicate for inclusion. In the event of disagreement or insufficient information in the abstract, we independently and in duplicate reviewed the full text of potential articles.7 The inter-rater agreement for study inclusion, as assessed using an intra-class correlation coefficient, was 0.69.7 Conflicts were resolved by consensus discussion between the two reviewers.

Data Extraction

We extracted data independently and in duplicate for all variables and resolved conflicts by consensus.

The information we extracted included the training level of learners, clinical topic, training location, study design, method of group assignment, outcomes, and methodological quality. We graded the methodological quality of the studies using the Medical Education Research Study Quality Instrument (MERSQI).9 We further coded the presence of simulation features identified in a review of simulation: mastery learning, distributed practice (whether learners trained on 1 or >1 day), feedback (low = rare and unstructured; medium = brief, sporadic and unstructured from 1 to 2 sources; high = substantive, structured and intensive, from at least 2 sources), curriculum integration (the simulation intervention as a required element of the curriculum), and group vs. solo learning.10 We coded the time engaged in SBME and whether or not hands-on practice on the simulator occurred (defined as direct contact with the simulator as opposed to listening with group stethoscopes).

We abstracted information separately for all outcomes. We defined knowledge outcomes as assessments of factual recall, conceptual understanding, or application of knowledge. Skill outcomes were assessments of the learners’ cardiac physical examination proficiency in a simulated environment. Skill outcomes included the use of standardized patients or real patients brought in for assessment purposes only (e.g., not part of usual clinical practice). No studies examined learners in clinical practice. If multiple measures of a skill outcome were reported, we selected a single outcome using the following order of priority: (1) outcomes assessed in a different setting (e.g., different simulator or standardized patients) over those assessed in the simulator used for training, (2) the author-defined primary outcome, or (3) a global or summary measure of effect.

Data Synthesis

We classified studies as no-intervention comparison if they were a single group pre-post design or a two-group study where simulation was added to other instruction common to all learners. We classified all other two-group studies as other-comparison (comparison to another type of educational intervention) or simulation-comparison (comparison of two simulation-based interventions). We planned to quantitatively synthesize the results of all classifications with more than three studies.

As we have described previously,7 for each reported outcome we calculated the standardized mean difference (Hedges’ g effect size) using accepted techniques.11–13 We contacted primary authors directly if additional outcome information was needed.

We quantified the inconsistency (heterogeneity) across studies using the I2 statistic.14 I2 estimates the percentage of variability across studies above that expected by chance, and values >50 % indicate large inconsistency. Due to large inconsistency in our analyses, we used random effects models to pool weighted effect sizes.

We conducted planned subgroup analyses based on selected instructional design features (presence of curricular integration, feedback, and individual hands-on practice), type of simulator (Harvey® and other simulators considered separately), and study design (1 vs. 2 group designs). We performed sensitivity analyses excluding (1) nonrandomized studies, (2) low total quality score (MERSQI < 12), and (3) studies that used p value upper limits or imputed standard deviations to estimate the effect size. We calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient to examine the relationship between minutes of practice and effectiveness of SBME.

We used funnel plots and the Egger asymmetry test to explore possible publication bias.15 We used trim and fill (random effects) to estimate revised pooled effect sizes, although this method has noted limitations in the presence of high inconsistency.16

We used SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for all analyses. Statistical significance was defined by a two-sided alpha of 0.05. Determinations of clinical significance emphasized Cohen’s effect size classifications (0.2–0.49 = small; 0.5–0.8 = moderate, and >0.8 = large).17

RESULTS

Trial Flow

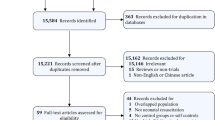

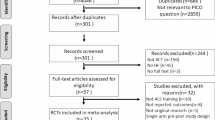

Using our search strategy, we identified 10,297 articles with an additional 607 identified from our review of reference lists and journal indices. From these we identified 18 articles for inclusion (Fig. 1, Table 1).

Study Characteristics

We identified 13 single group pre-post studies or two group studies with simulation added to common instruction (classified as no-intervention studies),4,18–29 3 studies comparing SBME to another instructional modality,30–32 and 2 studies comparing simulation to another simulation modality33,34 (Table 1). The majority of learners were medical students, but residents, attending physicians, nursing students, nurses, and osteopathic internists (attendings, residents and students) were also among the study participants. A single simulator (Harvey® Laerdal Medical, Miami, FL, USA) was used in the majority of studies for both outcomes. The skill outcomes were assessed with simulated heart sounds in 14 of the 18 studies. Five studies assessed auscultatory skill using patients with real cardiac findings, and 1 study assessed cardiac physical exam technique using a standardized patient without cardiac findings.29

Examining instructional design features of the 18 studies, 8 studies used a curriculum distributed over more than 1 day, 7 studies embedded the intervention within their curriculum, 1 study employed high feedback, 1 study employed mastery learning, and in 8 studies the learner engaged in hands-on practice (e.g., direct contact) with the simulator.

Study Quality

Of the 13 no-intervention comparison studies, 3 were randomized comparative studies. Two of the other-comparison studies were randomized, as were the simulation-simulation comparison studies. Blinded assessment of outcomes was done in 11 of 18 studies. Six studies lost more than 25 % of participants prior to outcome evaluation or failed to report follow-up. One study used a self-reported skill; all other outcomes were determined objectively. The mean study quality as assessed by MERSQI was 11.8 ± 1.9; MERSQI scores for each study are provided in Table 1.

Quantitative Meta-Analysis of No-Intervention Comparison Studies

We pooled data using meta-analysis for the 13 single-group pre-post studies or two group studies with simulation added to common instruction. Six of these studies assessed knowledge outcomes in 343 learners (Fig. 2), and 10 studies assessed skill outcomes in 1,074 learners (Fig. 3). Meta-analysis of these studies demonstrated that simulation-based instruction in cardiac auscultation was effective, with large pooled effect sizes of 1.10 (95 % CI 0.49–1.72; p < 0.001; I2 = 92.4 %) for knowledge outcomes and 0.87 (95 % CI 0.52–1.22; p < 0.001; I2 = 91.5 %) for skill outcomes (Figs. 2 and 3, respectively).

Funnel plots and Egger tests suggested the possibility of publication bias (on-line Appendices A and B). Trim and fill analysis yielded an adjusted effect size for the knowledge outcome of 0.78 (95 % CI, 0.03 to 1.53; p = 0.04) and for the skills outcome of 0.57 (95 % CI, 0.12 to 1.02; p = 0.01).

We display the effect sizes for the pre-planned subgroup and sensitivity analyses in Table 2. Use of a two-group study design and higher-quality studies as assessed by MERSQI yielded statistically significant smaller effect sizes. Among the instructional design features, studies incorporating hands-on practice (direct contact with the simulator) were associated with consistently larger effect sizes for both knowledge and skill compared to studies without hands-on practice, although this difference was not statistically significant. Curricular integration did not have a consistent association with effect size. As only one study had high feedback, this planned subgroup analysis was uninformative.

In correlation analyses, the association between time on task and effect size was r = 0.76 (p = 0.08; N = 6) for knowledge outcomes and r = 0.59 (p = 0.07; N = 10) for skills outcomes.

Narrative Review of Comparative Effectiveness Studies

When simulation was compared to another instructional modality in three studies, there was little to no relative benefit to knowledge and skill acquisition (Fig. 4). One of these randomized trials compared a CPS to a CD of recorded heart sounds and demonstrated no significant difference in skills, although the CD group was exposed to more examples of each murmur compared to the CPS group.30

One of the non-randomized studies compared SBME with bedside instruction and demonstrated a statistically significant benefit of SBME for both knowledge and skills outcomes.31 The other non-randomized study showed no difference in knowledge between students who used a multimedia computer system with a CPS and students who used the same computer program with videos.32

Two of these three studies were of high methodological quality,30,31 and two assessed skill using patients with real cardiac findings.30,31

There were inconsistent benefits of simulation on skill acquisition in the simulation-comparison studies (Fig. 4). One randomized trial of high methodological quality compared listening to simulated heart sounds with and without palpatory cues. The results demonstrated improvement in auscultatory skills from pre-test to post-test but no difference in skills between the two groups.34 The other study randomized medical students to learn mitral regurgitation, aortic stenosis, or right ventricular strain without a murmur using a CPS.33 When tested on a real patient with mitral regurgitation, the group who learned this disorder on the CPS identified more clinical features and had higher diagnostic accuracy than the other two groups.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis suggest SBME is an effective instructional approach for teaching cardiac auscultation. The pooled results for 13 single-group pre-post studies or two group studies with simulation added to common instruction indicate a positive effect, and this finding was consistent in subgroup and sensitivity analyses and for both knowledge and skills outcomes. Among the three studies comparing SBME to another instructional modality, SBME showed few or no benefits on knowledge and skill acquisition relative to the other modality such as recorded heart sounds or real patients. The two simulation comparison studies demonstrated inconsistent benefits. In one of these studies, the results demonstrated transfer of skills for the same murmur presented on the simulator and a real patient, but a lack of transfer from simulated murmurs that were different from the real patient’s diagnosis.33 We conclude that strong evidence supports SBME as an effective instructional approach to cardiac physical exam teaching and that limited evidence suggests it is comparable to other available modalities.

Of importance to undergraduate MD course directors and post-graduate program directors is how to use SBME effectively. Our data yield a few practical suggestions. First, direct contact (hands-on practice) with the simulator appears to increase the effectiveness of cardiac skills acquisition. This likely relates to increasing the opportunity for repetitive practice35 and deliberate practice,5 both of which are known to have positive educational impacts.

Second, curricular integration of the SBME cardiac physical examination course does not appear to be an important instructional design feature, and it can be implemented as a stand-alone intervention. This contrasts with other authors who suggest that integration is key.10 This unexpected finding may be due to the fact that skill in cardiac auscultation is a competency that crosses many disciplines and content domains. Its specific placement within a curriculum may be less relevant than the importance of including it at all.

Third, more time engaged in learning simulation-based cardiac physical examination may lead to better learning outcomes. Consistent with a previous review of repetitive practice,36 and views generally accepted among medical educators, time on task had a moderate correlation with learning outcomes (explaining 58 % and 35 % of the variance in knowledge and skill outcomes, respectively). The lack of statistical significance likely reflects the relatively small sample of studies available for statistical pooling.

Limitations and Strengths

The strengths of this review include the comprehensive search strategy, rigorous data extraction, and subgroup analyses addressing focused, pre-specified between-study differences.

Our review is limited primarily by the quantity of published evidence, which reduced the statistical power of subgroup analyses. Although comparisons with active interventions (e.g., comparative effectiveness studies) would yield the strongest recommendations for educational best practices, there were only five studies of this type, with variable results. We also found high inconsistency between individual study results. Such inconsistency may plausibly arise from differences in the intensity or effectiveness of the intervention, the measurement of the outcome, or the study design. In exploring these inconsistencies we found that studies with stronger methods (higher MERSQI scores and two-group designs) had lower effect sizes, and those with more precise estimation of effect size had higher effect sizes, suggesting that these methodological differences could account for some of this inconsistency. More importantly, we note that this inconsistency varied in the magnitude but not the direction of benefit, suggesting that SBME is consistently effective but that some interventions are more effective than others.

Funnel plots suggested the possibility of publication bias among the studies, and adjustments attempting to compensate yielded smaller effect sizes than those suggested in the overall meta-analysis. However, methods for detecting and adjusting for publication bias are imprecise.16

Integration with Prior Research

To our knowledge, there are no previous systematic reviews focused solely on teaching cardiac auscultation skills. Our results are consistent with previous reviews that show large benefits from SBME with a preponderance of comparisons with no intervention.5,7

The subgroup analyses we chose to explore were based on a previous narrative review of effective SBME design features.10 Although subgroup analyses should be interpreted cautiously, as they reflect between-group rather than within-group analyses and are thus susceptible to confounding,37 it appears as though direct contact (hands-on practice) with the simulator is an important teaching technique and that the teaching of cardiac auscultation can be situated anywhere within the curriculum.

Unfortunately, only one study provided learners with high levels of feedback, which we defined as a substantial component of the educational intervention with feedback coming from more than one source. This result came as a surprise, since feedback is generally considered a key element of effective SBME instruction.10 More broadly within medical education, the presence of feedback has an independent positive effect on clinical performance,38 and based on this literature educators might consider how to augment the feedback that learners receive during cardiac auscultation training. This instructional design feature warrants further study in SBME. Other instructional design features, such as mastery learning, were present in too few studies to be analyzed.

Implications for Future Research

This meta-analysis demonstrates that SBME is an effective educational strategy for teaching cardiac auscultation skills. Given the consistent, positive benefits of SBME demonstrated in single-group pre-post studies and two-group studies with simulation added to common instruction, additional studies with these designs are not required. Future studies should focus on comparing key instructional design features either between simulations or comparing SBME to another educational modality, using rigorous and reproducible outcome measures, and assessing diagnostic skill in real clinical practice to elucidate the best practices for this expensive resource.

REFERENCES

Conn RD, O’Keefe JH. Cardiac physical diagnosis in the digital age: an important but increasingly neglected skill (from stethoscopes to microchips). Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(4):590–5.

Mangione S, Nieman LZ, Gracely E, Kaye D. The teaching and practice of cardiac auscultation during internal medicine and cardiology training: a nationwide survey. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(1):47.

Vukanovic-Criley JM, Criley S, Warde CM, Boker JR, Guevara-Matheus L, Churchill WH, et al. Competency in cardiac examination skills in medical students, trainees, physicians, and faculty: a multicenter study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(6):610–6.

Gordon MS, Ewy GA, Felner JM, Forker AD, Gessner I, McGuire C, et al. Teaching bedside cardiologic examination skills using “Harvey”, the cardiology patient simulator. Med Clin North Am. 1980;64(2):305–13.

McGaghie WC, Issenberg SB, Cohen ER, Barsuk JH, Wayne DB. Does simulation-based medical education with deliberate practice yield better results than traditional clinical education? A meta-analytic comparative review of the evidence. Acad Med. 2011;86(6):706–11.

Passiment M, Sacks H, Huang G. Medical Simulation in Medical Education: Results of an AAMC Survey. Association of American Medical Colleges. Washington DC: 2011 Sept. pp.1-48.

Cook DA, Hatala R, Brydges R, Zendejas B, Szostek JH, Wang AT, et al. Technology-enhanced simulation for health professions education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;306(9):978–88.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–12.

Reed DA, Cook DA, Beckman TJ, Levine RB, Kern DE, Wright SM. Association between funding and quality of published medical education research. JAMA. 2007;298(9):1002–9.

Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Petrusa ER, Lee Gordon D, Scalese RJ. Features and uses of high-fidelity medical simulations that lead to effective learning: a BEME systematic review. Med Teach. 2005;27(1):10–28.

Borenstein M. Effect sizes for continuous data. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC, eds. The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis. 2nd ed. New York: Russell Sage; 2009.

Morris SB, DeShon RP. Combining effect size estimates in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-groups designs. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):105–25.

Hunter J, Schmidt F. Methods of Meta-Analysis: Correcting Error and Bias in Research Findings. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2004.

Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–34.

Terrin N, Schmid CH, Lau J, Olkin I. Adjusting for publication bias in the presence of heterogeneity. Stat Med. 2003;22(13):2113–26.

Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc; 1988.

Penta FB, Kofman S. The effectiveness of simulation devices in teaching selected skills of physical diagnosis. J Med Educ. 1973;48(5):442–5.

Woolliscroft JO, Calhoun JG, Tenhaken JD, Judge RD. Harvey: the impact of a cardiovascular teaching simulator on student skill acquisition. Med Teach. 1987;9(1):53–7.

Harrell JS, Champagne MT, Jarr S, Miyaya M. Heart sound simulation: how useful for critical care nurses? Heart Lung. 1990;19(2):197–202.

Oddone EZ, Waugh RA, Samsa G, Corey R, Feussner JR. Teaching cardiovascular examination skills: results from a randomized controlled trial. Am J Med. 1993;95(4):389–96.

Takashina T, Shimizu M, Katayama H. A new cardiology patient simulator. Cardiology. 1997;88(5):408–13.

Issenberg S, Gordon DL, Stewart GM, Felner JM. Bedside cardiology skills training for the physician assistant using simulation technology. Perspect Physician Assist Educ. 2000;11(1):99–103.

Issenberg SB, McGaghie WC, Gordon DL, Symes S, Petrusa ER, Hart IR, et al. Effectiveness of a cardiology review course for internal medicine residents using simulation technology and deliberate practice. Teach Learn Med. 2002;14(4):223–8.

Issenberg SB, Gordon MS, Greber AA. Bedside cardiology skills training for the osteopathic internist using simulation technology. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2003;103(12):603–7.

Fraser K, Peets A, Walker I, Tworek J, Paget M, Wright B, et al. The effect of simulator training on clinical skills acquisition, retention and transfer. Med Educ. 2009;43(8):784–9.

Butter J, McGaghie WC, Cohen ER, Kaye M, Wayne DB. Simulation-based mastery learning improves cardiac auscultation skills in medical students. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(8):780–5.

Tiffen J, Corbridge S, Robinson P. Patient simulator for teaching heart and lung assessment skills to advanced practice nursing students. Clin Simul Nurs. 2011;7(3):e91–7.

Kern DH, Mainous AG III, Carey M, Beddingfield A. Simulation-based teaching to improve cardiovascular exam skills performance among third-year medical students. Teach Learn Med. 2011;23(1):15–20.

de Giovanni D, Roberts T, Norman G. Relative effectiveness of high- versus low-fidelity simulation in learning heart sounds. Med Educ. 2009;43(7):661–8.

Ewy GA, Felner JM, Juul D, Mayer JW, Sajid AW, Waugh RA. Test of a cardiology patient simulator with students in fourth-year electives. J Med Educ. 1987;62(9):738–43.

Waugh RA, Mayer JW, Ewy GA, Felner JM, Issenberg BS, Gessner IH, et al. Multimedia computer-assisted instruction in cardiology. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(2):197–203.

Fraser K, Wright B, Girard L, Tworek J, Paget M, Welikovich L, et al. Simulation training improves diagnostic performance on a real patient with similar clinical findings. Chest. 2011;139(2):376–81.

Champagne MT, Harrell JS, Friedman BJ. Use of a heart sound simulator in teaching cardiac auscultation. Focus Crit Care. 1989;16(6):448–56.

Barrett M, Kuzma M, Seto T, Richards P, Mason D, Barrett D, et al. The power of repetition in mastering cardiac auscultation. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):73–5.

McGaghie WC, Issenberg SB, Petrusa ER, Scalese RJ. Effect of practice on standardised learning outcomes in simulation-based medical education. Med Educ. 2006;40(8):792–7.

Oxman A, Guyatt G. When to believe a subgroup analysis. In: R H, ed. Users Guides Interactive. Chicago, IL: JAMA Publishing Group; 2002.

Veloski J, Boex JR, Grasberger MJ, Evans A, Wolfson DB. Systematic review of the literature on assessment, feedback and physicians’ clinical performance: BEME Guide No. 7. Med Teach. 2006;28(2):117–28.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ryan Brydges, Patricia Erwin, Stanley J. Hamstra, Jason Szostek, Amy Wang, and Ben Zendejas for their assistance with literature searching, abstract reviewing, and data extraction.

Funding/Support

This work was supported by intramural funds, including an award from the Division of General Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic.

Role of Sponsors

The funding sources for this study played no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation of the manuscript. The funding sources did not review the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest. There was no industry relationship with this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McKinney, J., Cook, D.A., Wood, D. et al. Simulation-Based Training for Cardiac Auscultation Skills: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J GEN INTERN MED 28, 283–291 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2198-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2198-y