ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

Numerous instruments have been developed to assess spirituality and measure its association with health outcomes. This study’s aims were to identify instruments used in clinical research that measure spirituality; to propose a classification of these instruments; and to identify those instruments that could provide information on the need for spiritual intervention.

METHODS

A systematic literature search in MEDLINE, CINHAL, PsycINFO, ATLA, and EMBASE databases, using the terms “spirituality" and “adult$," and limited to journal articles was performed to identify clinical studies that used a spiritual assessment instrument. For each instrument identified, measured constructs, intended goals, and data on psychometric properties were retrieved. A conceptual and a functional classification of instruments were developed.

RESULTS

Thirty-five instruments were retrieved and classified into measures of general spirituality (N = 22), spiritual well-being (N = 5), spiritual coping (N = 4), and spiritual needs (N = 4) according to the conceptual classification. Instruments most frequently used in clinical research were the FACIT-Sp and the Spiritual Well-Being Scale. Data on psychometric properties were mostly limited to content validity and inter-item reliability. According to the functional classification, 16 instruments were identified that included at least one item measuring a current spiritual state, but only three of those appeared suitable to address the need for spiritual intervention.

CONCLUSIONS

Instruments identified in this systematic review assess multiple dimensions of spirituality, and the proposed classifications should help clinical researchers interested in investigating the complex relationship between spirituality and health. Findings underscore the scarcity of instruments specifically designed to measure a patient’s current spiritual state. Moreover, the relatively limited data available on psychometric properties of these instruments highlight the need for additional research to determine whether they are suitable in identifying the need for spiritual interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Over the last 15 years, numerous studies on the relationship between spirituality and health have been published in different fields of research such as medicine, nursing, sociology, psychology, and theology. Initially most researchers investigated the association between religiousness or religion, and health1,2. However, the relative decline of the Judaeo-Christian religions in Western societies has led researchers to consider the broader concept of spirituality3–6.

Clinical research on the relationship between spirituality and health finds that spirituality is a critical resource for many patients in coping with illness, and is an important component of quality of life, especially for those suffering chronic or terminal diseases7,8. However, some aspects of spirituality have been negatively associated with health outcomes. For example, low spiritual well-being and religious struggle have been associated with higher mortality rates, more severe depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death.9,10 These observations have led clinicians to agree about the importance of assessing and addressing spiritual issues in health care settings11,12.

Promoting spiritual assessment and offering spiritual interventions within routine health care settings require a strong evidence base of clinical research. The foundation of such work is the availability of valid spiritual assessments that are appropriate in clinical settings. Hampering these efforts is the fact that, at present, no definition of spirituality is universally endorsed and no consensus exists on the dimensions of spirituality within health research5. As a result, numerous conceptualizations of spirituality have emerged6, making it difficult to understand the different constructs and aims of instruments that assess spirituality. Moreover, it is unknown whether some of these instruments would also be appropriate in clinical settings to assess a patient’s current spiritual state and to determine the need for spiritual intervention. These are important information gaps that must be addressed to improve the assessment of spirituality within health care.13

Several authors have tried to develop a catalogue of instruments to assess spirituality,14–18 but these reviews were not systematic, limited to specific populations, and essentially provided only descriptive information. To-date, no systematic review has been performed to catalogue and classify available instruments to assess spirituality within clinical health care research.

The purpose of this study is to provide a systematic review of instruments used in clinical research to assess spirituality. Additional objectives are: (1) to develop a conceptual and functional typology for classifying these instruments in order to assist researchers and clinicians in selecting the most appropriate instrument for their purposes; and (2) to identify instruments that could potentially be used to investigate patients’ current spiritual state and identify the need for spiritual intervention in a clinical setting.

METHODS

Working definitions of the constructs of spirituality and religion4–6,19–23 that informed the present study are summarized in Box 1.

Search Strategy

A literature search, not restricted by language, was performed in Ovid MEDLINE (1948 to January 2011), Ovid ATLA Religion (1949 to November 2010), Ovid PsycINFO (1806 to January 2011), CINHAL-Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (1993 to January 2011), and EMBASE (1980 to January 2011) electronic databases, using the term “spirituality” and “adult$.” This search was limited to Human and to All journal articles.

First, three independent reviewers (SM, ER, and SR) selected citations that might have included a spiritual assessment instrument used to investigate the association between spirituality and health (physical or mental), health-related quality of life, or any other clinical outcome (e.g., health services used). Articles were selected based on the review of the abstract. The full text was examined when information about the instrument was not available in the abstract. Papers were excluded if: (1) an instrument to assess spirituality was not used (e.g., position paper, surveys, qualitative studies); (2) they investigated spirituality or attitudes toward spirituality/religiosity among health professionals, chaplains, or family members; (3) only measures of religiousness were used (e.g., religious affiliation, frequency of church attendance); (4) they used an instrument without a specific construct of spirituality (i.e., global quality of life); or (5) spirituality was assessed with a single item (e.g., “How spiritual do you consider yourself?”).

For the three searches, inter-rater agreements between reviewers for citation selection ranged from 82% to 98%.

Selected papers were then subjected to further, in-depth examination to retrieve instruments proposed to measure spirituality. Instruments were excluded if: (1) they consisted solely of religiousness items; (2) they assessed only one dimension related to spirituality without the aim to measure spirituality itself (e.g., hope, serenity, purpose in life); (3) there was no evidence that the instrument had been used with clinical outcomes; and (4) no data were available on the psychometric properties of the instrument in a referenced journal.

Finally, the reference lists in the selected papers were also systematically reviewed to identify additional instruments. At the end of this process, scholars and researchers in the field of religion and spirituality were asked to identify any additional instruments meeting our inclusion and exclusion criteria. The list serve of the Religion, Spirituality and Aging formal interest group of the Gerontological Society of America was also used to query researchers and clinicians involved in work on spirituality.

Data on Instruments

For each instrument, the dimensions underlying the construct of spirituality were identified, as well as the intended goals of the instrument. Data on the psychometric properties, defined as described in Box 2 24,25, were systematically recorded. When information on correlations with other instruments was available, only those with measures of spirituality and religiousness are reported in this paper to examine criterion validity. Data on concurrent validity were also extracted when available. Furthermore, studies in which the instruments were correlated with (cross-sectional studies) or predictive of (longitudinal studies) health outcomes were also retrieved from the systematic search to examine this aspect of concurrent and predictive validity.

For each instrument, an assessment of the comprehensiveness of its validation process was performed, using a score specifically developed for the purpose of this study (see Online Appendix 1). This score was built on the basis of recognized standards in instrument development24,25. This score summarizes the reporting on the content (construct definition, instrument development), internal structure (factor analysis), reliability (internal consistency and test-retest), and validity (criterion validity and concurrent validity) of the instrument. Scores range from 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating a more comprehensive validation process.

Classification of Instruments to Assess Spirituality

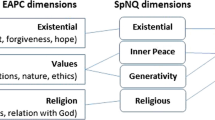

The development of instruments aimed at assessing spirituality can be conceived as a two-step process (see Fig. 1). The first step would be the definition of the conceptual aspect of spirituality that the instrument intends to assess. The second step would be the definition of items that operationalize the spirituality concept in question. In this review, we propose a classification of instruments that follows this line of reasoning in instrument development.

Conceptual Classification

-

1.

This classification is based on the underlying concept of spirituality that the instrument mainly intends to capture from the point of view of the authors who developed the instrument. Four common categories of measures are described: general spirituality, spiritual well-being, spiritual support or coping, and spiritual needs.

Functional Classification

-

2.

This classification is based on the examination of all items within the instrument. Three categories of items are proposed, according to the expression of spirituality they intend to capture:26,27

-

1.

Measures of cognitive expressions of spirituality: these items intend to measure attitudes and beliefs toward spirituality (e.g., “Do you believe meditation has value?”). These measures have been shown to be relatively stable within individuals over time28.

-

2.

Measures of behavioral expressions (public or private practices) of spirituality (e.g., “How often do you go to church?”). These measures are also supposed to be stable over time.29

-

3.

Measures of affective expressions of spirituality: these items intend to capture feelings associated with spirituality (e.g., “Do you feel peaceful?”). These measures illustrate the patient’s spiritual state, which is not necessarily stable over time. Spiritual states might change over time along a hypothesized spectrum of wellness ranging from spiritual well-being to spiritual distress. A spiritual state might be worse because of external stressors such as illness or bereavement, or improved by spiritual intervention.30

Retrieval of Instruments Comprising Items Measuring a “Current” Spiritual State

According to the functional classification described above, among instruments measuring affective expression of spirituality, those using items that measured a current spiritual state were further selected by three reviewers (SM, ER, and EM). A triple abstraction process was used, each reviewer being blinded to results from the others. Instruments containing at least one question of spiritual state at the time of assessment were retrieved.

Initial agreement for classification was very good (Fleiss kappa 0.88, p < 0.001)31. Disagreements between reviewers were discussed and resolved through consensus.

RESULTS

Literature Search

The search strategy (see Fig. 2) identified 1,575 citations in Ovid Medline, ATLA, and PsycINFO databases. The search in CINHAL database identified 356 citations. Finally, the search in EMBASE database identified 1,360 citations, for a total of 3,291 citations.

From these 3,291 citations, 2,854 were excluded because they did not use an instrument to assess spirituality (N = 2,068); investigated spirituality in health professionals, chaplains, children, or family instead of patients (N = 513); focused solely on religiousness measures (N = 154); used an instrument to measure quality of life without a specific focus on spirituality (N = 86); used a single-item question (N = 33).

Among the remaining 437 citations, 63 instruments assessing spirituality were identified. Among these, 3 were excluded because they exclusively measured religiousness, 12 were excluded because they investigated a domain related to spirituality, but not spirituality per se (e.g., the Herth Hope Scale 32, the Meaning in Life scale 33, or the Serenity Scale 34), 10 were excluded because they were not used in studies measuring health outcomes, and finally 5 instruments were excluded because no psychometric properties were available for the instrument.

At the end of the process, two additional instruments were identified from the citations and the input of experts in the field: the Spiritual Beliefs Questionnaire, 35 (from references) and the Spiritual Strategies Scale 36 (from experts).

Thus, 35 instruments used to measure spirituality in clinical research were identified in this systematic search of the literature. Several instruments also had abbreviated forms that were subsequently developed. These are considered as the same instrument in this review.

Instruments to Assess Spirituality

Table 1 lists the selected instruments to assess spirituality 7,22,28,35–76 and provides summary information on each instrument. Table 1 also displays correlations between these spirituality measures and health outcomes from cross-sectional studies (concurrent validity), as well as data available from prospective studies that investigated the predictive value of these instruments on health outcomes (predictive validity). Additional information on each instrument can be found in an online Appendix Table (Online Appendix 2). Particular observations about the instruments are provided below.

Validation Population and Psychometric Properties

The instrument validated in the largest and most diverse population is the World Health Organization’s Quality Of Life Instrument—WHOQOL—Spirituality, Religion and Personal Beliefs 66 (WHOQOL-SRPB). It was validated using 5,087 participants in 18 countries around the world. The Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality 40–42 was also validated in a large sample, but only composed of participants in the United States (N = 1,445). When considering specific validation in medical patients, the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-spiritual well being (FACIT-Sp) 7,65 was validated in the largest sample (N = 1,617 patients) comprised of individuals with cancer (83%) or HIV/AIDS (17%).

The clinical populations most frequently studied for instrument validation were those with severe life-threatening or chronic diseases (e.g., cancer, HIV/AIDS, terminally ill; 34%). Six instruments were initially validated only in student samples22,28,45,60,64,72, but were further used in clinical research with health outcomes, either in the same initial student population72 or in later studies with patients (see Table 1). Overall, only three instruments had been validated in older persons,36,67–69 and only one instrument was validated with nursing home residents. 54,55

In general, data on psychometric properties of the instruments were incomplete, but some important trends did emerge. First, criterion-related validity with religiousness measures or with other spirituality measures was frequently reported (54%). As no “gold standard” measure of spirituality exists, the instruments most frequently used to establish such validity were measures of religiosity (e.g., Hoge Intrinsic Religious Motivation Scale, Duke Religion Index). However, five studies 28,42,43,60,69 also used the Spiritual Well-being Scale22 as a measure of criterion validity. Second, data on concurrent validity were reported for 48% of the instruments. Domains most frequently chosen to assess concurrent validity were quality of life, psychological states, life satisfaction, or depression. Third, data on longitudinal predictive validity were scarce as most studies had cross-sectional designs and very few instruments have been used in prospective studies. Nevertheless, we found prospective data on predictive validity from other studies retrieved from the systematic search for six instruments7,22,38,45,49,60. Results show that measures of spirituality might be predictive of: (1) reduced drug use in drug treatment patients (Spiritual Well-Being Scale 22 , Spiritual Transcendence Scale 45); (2) better quality of life and decline of depressive symptoms in cancer survivors (FACIT-Sp 7); and (3) reduced long-term care utilization in older patients (Daily Spiritual Experience Scale 38). Finally, little information regarding sensitivity to change was found in prospective studies77–81 that mostly used the Spiritual Well-being Scale 22 and the FACIT-Sp 7 scales. Results are essentially inconclusive as most of these studies do not report any significant change in spirituality measures, despite significant changes in measures of quality of life.

Quality scores assessing the comprehensiveness of the instrument development and validation process revealed that most instruments had good scores, but only three had a perfect score of 6 out of 6 (i.e., The Ironson-Woods Spirituality/Religiousness Index 61, The Spiritual Well-Being Scale 22, and The Spirituality Index of Well- Being 68 ). The most frequent validation weakness was the lack of a test-retest measure, which was reported in less than half of the instruments (13/35).

Classification of Instruments to Assess Spirituality

Conceptual Classification

This classification (see Table 1) is based on the construct of spirituality the instrument is intended to assess. Twenty-two instruments were classified as measures of general spirituality.20,37–64 These instruments are usually multidimensional measures and have various purposes, such as measuring expressions of spirituality, spiritual beliefs, or spiritual experiences. Five instruments were classified as measures of spiritual well-being7,22,66–68. Four instruments were considered as measures of spiritual coping or spiritual support.36,70–72 Finally, four instruments were categorized as measures of spiritual needs73–76.

Functional Classification

This classification is based on the definition of three categories of items (i.e., cognitive, behavioral, and affective), according to the spiritual expressions these items intend to capture (see Table 1). Almost all instruments include items that investigate cognitive (34/35) and affective aspects of spirituality (26/35). Overall, 15 of the 35 instruments combined all three different functional dimensions (i.e., cognitive, behavioral, and affective).

Instruments Comprising Items Measuring a Current Spiritual State

Table 2 provides more detailed information on the 16 instruments that include items measuring a current spiritual state.

Overall, purpose and meaning in life were the spirituality domains most frequently examined. Nine instruments include questions inquiring about meaning or purpose in life (e.g., “To what extent do you feel meaning in life”). Other domains frequently investigated were life satisfaction (e.g., “I am satisfied with my life”), peacefulness (e.g., “To what extent do you have inner peace?”), and self-esteem (e.g., “I feel good about myself).

Only three instruments have at least half of their items focusing on current spiritual state. Two of these instruments have a spiritual well-being construct (i.e., the FACIT-Sp 7 and the Spirituality Index of Well-being 68) and are intended to assess the patient’s level of spiritual well-being. These two instruments underwent an extensive validation process (scoring 5 and 6, respectively, on the scale to assess validation comprehensiveness). One instrument has a spiritual needs construct (the Spiritual Needs Inventory 73 ). However, this instrument underwent a less accurate validation process (score = 4).

In conclusion, the FACIT-Sp 7 and the Spirituality Index of Well-being 68 clearly emerged as the most well-validated instruments for the assessment of a patient’s current spiritual state.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review identified 35 instruments used in clinical health research to assess spirituality. A unique contribution of this review is to offer a clear description of the constructs and aims of these instruments and to highlight the different aspects of spirituality these instruments are intended to capture. The typology of these instruments using two complementary classifications should help professionals interested in the field of spirituality and health in choosing the most appropriate instrument for their research or clinical purposes. Those interested should first define the type of concept of spirituality (e.g., spiritual well-being) they wish to assess and then choose the appropriate instrument regarding the type of spiritual expression (cognitive, behavioral, or affective expressions) assessed by the instrument (Table 1).

Another important contribution of this review is to identify instruments able to measure a patient’s current spiritual state that could potentially determine the need for spiritual intervention82. Results show that only three instruments had at least half of their items focusing on the patient’s current spiritual state. Among them, the FACIT-Sp 7 and The Spirituality Index of Well-being 68 are considered the best candidates to assess the current spiritual state of patients. However, all these instruments focus on spiritual well-being, and none address the other end of the hypothesized spectrum of spiritual state (i.e., spiritual distress). Looking at spiritual state only from a “well-being” perspective may be problematic and limit the precision of the observation in individuals whose state belongs to the other end of the spectrum. It seems unlikely that the absence of spiritual well-being could merely be equivalent to a state of spiritual distress. Making this distinction is essential to determine more precisely those situations that could potentially require an intervention. Overall, these findings have important implications for the fields of spiritual assessment and interventions in clinical care settings.

This review also emphasizes the relatively limited data available on the psychometric properties of most instruments. First, assessment of test-retest reliability was limited. Second, when reported, criterion-related validity primarily used measures of religiousness as opposed to other measures of spirituality. Thus, relationships among instruments that share similar spirituality constructs were seldom reported, limiting the robustness of the instrument validation in many cases. Third, data on predictive validity were scarce. Finally, there were very few data on sensitivity to change, and retrieved results were essentially negative. However, the population enrolled in these studies had quite high levels of spiritual well-being at baseline, making it difficult to show any further improvement over time. This ceiling effect likely explains these negative results. These limitations should be addressed in future research in order to determine the level of change that would be considered meaningful and to accurately assess the effectiveness of interventions to improve a patient’s spiritual state82.

Finally, from a wider perspective, this review illustrates the diversity of the spirituality constructs used to develop these instruments and the resulting heterogeneity in their intended aims.

This systematic review has some limitations. First, instruments initially developed and used for other purpose than to investigate the relationship between spirituality and health were excluded. The extensive literature search identified instruments originating from psychological and theological research that were not specifically designed for use in clinical studies with health outcomes. Even though these instruments were excluded from this review, it is likely that some could also be applied in a clinical setting. Second, criteria used to include instruments in this review could be criticized as spirituality remains a broad, complex, and multidimensional concept that lacks definitional consensus. The exclusion of instruments designed on those dimensions only loosely related to spirituality seems logical (i.e., hope, peace), but the exclusion of instruments measuring broad concepts such as purpose or meaning in life is debatable. However, among the instruments that were excluded, the specific goal was not to measure spirituality per se.

This study has also clear strengths. First, a systematic and structured search was performed that used several databases and was complemented with input from experts in the field. In addition, the proposed functional classification was validated based on the triple-abstraction process that was performed by blinded reviewers, with very good agreement observed. Additional data from subsequent studies where these instruments have been used (e.g., data on concurrent and predictive validity) were systematically retrieved from the search. Finally, this review was not limited to English-language instruments, but also included some measures initially developed in French, German, and Korean.51,71,75

In conclusion, this systematic review provides detailed information on instruments to assess the complex relationship between spirituality and health. Results demonstrate the relative scarcity of instruments specifically designed to measure a patient’s current spiritual state. Most importantly, these results highlight the current absence of any instrument designed to measure poor spiritual well-being, such as spiritual distress. Finally, this study also identified several methodological gaps that should be addressed before implementing spiritual interventions into routine care. In particular, the ability of current instruments to monitor changes in spiritual state over time seems especially important to understand further if one wants to adequately document the effectiveness of spiritual interventions.

References

Koenig HG, McCullough ME, Larson DB. Handbook of religion and health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001.

Koenig HG, Larson DB. Religion and mental health: Evidence for an association. Int Rev Psychiatry 2001;13:67–78.

Shuman J, Meador K. Heal Thyself. Spirituality, Medicine, and the Distortion of Christianity. New York,NY: Oxford University Press; 2003.

Chandler CK, Holden JM, Kolander CA. Counseling for spiritual wellness: Theory and practice. Journal of Counseling & Development 1992;71:168–175.

Moberg DO. Assessing and measuring spirituality: Confronting dilemmas of universal and particular evaluative criteria. Journal of Adult Development 2002;9:47–60.

Miller WR, Thoresen CE. Spirituality, religion, and health: An emerging research field. Am Psychol 2003;58:24–35.

Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Mo M, Cella D. A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psychooncology 1999;8:417–428.

McClain CS, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W. Effect of spiritual well-being on end-of-life despair in terminally-ill cancer patients. Lancet 2003;361:1603–1607.

Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Tarakeshwar N, Hahn J. Religious struggle as a predictor of mortality among medically ill elderly patients: a 2-year longitudinal study. Arch Intern Med 2001;161(15):1881–1885.

Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Depression, hopelessness, and desire for hastened death in terminally ill patients with cancer. JAMA 2000;284(22):2907–2911.

Bell IR, Caspi O, Schwartz GE, et al. Integrative medicine and systemic outcomes research: issues in the emergence of a new model for primary health care. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:133–140.

Sulmasy DP. A biopsychosocial-spiritual model for the care of patients at the end of life. Gerontologist 2002;42 3:24–33.

Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the consensus conference. J Palliat Med 2009;12:885–904.

Sinclair S, Pereira J, Raffin S. A thematic review of the spirituality literature within palliative care. J Palliat Med 2006;9:464–479.

Mularski RA, Dy SM, Shugarman LR et al. A systematic review of measures of end-of-life care and its outcomes. Health Serv Res 2007;42:1848–1870.

Vivat B. Measures of spiritual issues for palliative care patients: a literature review. Palliat Med 2008;22:859–868.

Stefanek M, McDonald PG, Hess SA. Religion, spirituality and cancer: current status and methodological challenges. Psychooncology 2005;14:450–463.

Shorkey C, Uebel M, Windsor L. Measuring dimensions of spirituality in chemical dependence treatment and recovery: research and practice. Int J Ment Health Addiction 2008;6:286–305.

Zinnbauer BJ, Pargament KI, Cole B, et al. Religion and spirituality: Unfuzzying the fuzzy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 1997;36:549–564.

Allport GW, Ross JM. Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology 1967;5:432–443.

Koenig H, Parkerson GR, Jr., Meador KG. Religion index for psychiatric research. Am J Psychiatry 1997;154:885–886.

Ellison CW. Spiritual well-being: Conceptualization and measurement. J Psychol Theol 1983;11(4):330–340.

Moberg DO. Spiritual well-being: background and issues. Review of Religious Research 1984;25.

Stewart AL. Psychometric Considerations in Functional Status Instruments. In: Wonca Classification Committee, ed. Functional Status Measurement in Primary Care. New York: Springer-Verlag;1990; 3–26

Cook DA, Beckman TJ. Current concepts in validity and reliability for psychometric instruments: theory and application. Am J Med 2006;119:166–16.

Larson D, Swyers.J.P., McCullough ME. Scientific resaerch on spirituality and health: A consensus report. Larson D, Swyers.J.P., McCullough ME, editors. Bethesda MD, National Institute for Healthcare Research; 1998.

Thibault JM. A conceptual framework for assessing the spiritual functioning and fulfillment of older adults in long-term care settings. J Relig Gerontol 1991;7(4):29–45.

MacDonald D. Spirituality: Description, Measurement, and Relation to the Five Factor Model of Personality. J Pers 2000;68:153–197.

Idler EL, Kasl SV. Religion among disabled and nondisabled persons II: attendance at religious services as a predictor of the course of disability. J Gerontol Soc Sci 1997;52(6):S306-S316.

Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Emanuel LL. Attitudes and desires related to euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide among terminally ill patients and their caregivers. JAMA 2000;284:2460–2468.

Fleiss JL. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol Bull 1971;76:378–382.

Herth K. Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: development and psychometric evaluation. J Adv Nurs 1992;17(10):1251–1259.

Warner SC, Williams JI. The Meaning in Life Scale: determining the reliability and validity of a measure. J Chron Dis 1987;40:503–512.

Roberts KT, Aspy CB. Development of the Serenity Scale. J Nurs Meas 1993;1:145–164.

Christo G, Franey C. Drug users' spiritual beliefs, locus of control and the disease concept in relation to Narcotics Anonymous attendance and six-month outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend 1995;3:51–56.

Nelson-Becker H. Development of a spiritual support scale for use with older adults. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 2005;11:195–212.

Reed PG. Religiousness among terminally ill and healthy adults. Res Nurs Health 1986;9:35–41.

Underwood LG, Teresi JA. The daily spiritual experience scale: development, theoretical description, reliability, exploratory factor analysis, and preliminary construct validity using health-related data. Ann Behav Med 2002;24:22–33.

Howden JW. Development and psychometric characteristics of the Spirituality Assessment Scale. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Texas Women’s University;1992

Fetzer Institute National Institute on Aging. Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality of use in health research: a report of the Fetzer Institute on aging working group. Kalamazoo, MI: John E.Fetzer Institute ed.; 1999.

Idler EL, Musick MA, Ellison CG, et al. Measuring Multiple Dimensions of Religion and Spirituality for Health Research. Research on Aging 2003;25(4): 327–365.

Stewart C, Koeske GF. A Preliminary Construct Validation of the Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality Instrument: A Study of Southern USA Samples. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 2006;16(3):181–196.

Hatch RL, Burg MA, Naberhaus DS, Hellmich LK. The Spiritual Involvement and Beliefs Scale. Development and testing of a new instrument. J Fam Pract 1998;46:476–486.

Kass JD, Friedman R, Leserman J, Zuttermeister PC. Health outcomes and a new index of spiritual experience. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 1991;30:203–211.

Piedmont RL. Does spirituality represent the sixth factor of personality? Spiritual transcendence and the Five-Factor Model. J Pers 1999;67:985–1013.

Veach TL, Chappel JN. Measuring spiritual health: a preliminary study. Substance Abuse 1992;13(3):139–147.

Korinek AW, Arredondo RJ. The Spiritual Health Inventory (SHI): Assessment of an Instrument for Measuring Spiritual Health in a Substance Abusing Population. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly 2004; 22(2):55–66.

King M, Speck P, Thomas A. The Royal Free interview for religious and spiritual beliefs: development and standardization. Psychol Med 1995;25:1125–1134.

King M, Speck P,Thomas A. The Royal Free Interview for spiritual and religious beliefs: Development and validation of a self-report version. Psychol Med 2001;31(6):1015–1023.

Delaney C. The Spirituality Scale: Developement and Psychometric Testing of a Holistic Instrument to Assess the Human Spiritual Dimension. Journal of Holistic Nursing 2005;23:145–167.

Ostermann T, Bussing A, Matthiessen PF. Pilotstudie zur Entwicklung eines Fragebogens zur Erfassung der spirituellen und religiosen Einstellung und des Umgangs mit Krankheit (SpREUK). Forsch Komplementarmed Klass Naturheilkd 2004;11:346–353.

Bussing A, Ostermann T, Matthiessen PF. Role of religion and spirituality in medical patients: confirmatory results with the SpREUK questionnaire. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2005;3:10.

Bussing A, Matthiessen PF, Ostermann T. Engagement of patients in religious and spiritual practices: Confirmatory results with the SpREUK-P 1.1 questionnaire as a tool of quality of life research. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes 2005;3:53.

McSherry W, Draper P, Kendrick D. The construct validity of a rating scale designed to assess spirituality and spiritual care. Int J Nurs Stud 2002;39:723–734.

Wallace M, O'Shea E. Perceptions of spirituality and spiritual care among older nursing home residents at the end of life. Holistic Nursing Practice 2007; 21(6): 285–289.

LeBron McBride J, Lloyd Pilkington, Gary Arthur. Development of a Brief Pictorial Instruments for Assessing Spirituality in Primary Care. J Ambulatory Care Manage 1998;21:53–61.

Rowan NL, Faul AC, Cloud RN, Huber R. The Higher Power Relationship Scale: a validation. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions 2006;6:81–95.

Goldfarb LM, Galanter M, McDowell D, Lifshutz H, Dermatis H. Medical student and patient attitudes toward religion and spirituality in the recovery process. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 1996;22:549–561.

Galanter M, Dermatis H, Bunt G, Williams C, Trujillo M, Steinke P. Assessment of spirituality and its relevance to addiction treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 2007; 33:264.

Genia V. The Spiritual Experience Index: Revision and reformulation. Review of Religious Research 1997;38:344–361.

Ironson G, Solomon GF, Balbin EG, et al. The Ironson-woods Spirituality/Religiousness Index is associated with long survival, health behaviors, less distress, and low cortisol in people with HIV/AIDS. Ann Behav Med 2002;24:34–48.

King M, Jones L, Barnes K, et al. Measuring spiritual belief: Development and standardization of a Beliefs and Values Scale. Psychol Med 2006;36:417–425.

Seidlitz L, Abernethy AD, Duberstein PR, Evinger JS, Chang TH, Lewis BL. Development of the Spiritual Transcendence Index. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 2002;41:439–453.

Hodge D. A new six-item instrument for assessing the salience of spirituality as a motivational construct. J of Social Service Research 2003;30(1):41–61.

Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med 2002;24:49–58.

WHOQOL SRPB Group. A cross-cultural study of spirituality, religion, and personal beliefs as components of quality of life. Soc Sci Med 2006; 62:1486–1497.

Hungelmann J, Kenkel-Rossi E, Klassen L, Stollenwerk R. Development of the JAREL spiritual well-being scale. In: Carrol-Johnson RM, editor. Classification of Nursing Diagnosis:proceedings of the eight conference, North American Diagnosis Association. Philadeplphia: JB Lippincott, 1989:393–398

Daaleman TP, Frey BB, Wallace D, Studenski S. The Spirituality Index of Well-Being: Development and testing of a new measure. J Fam Pract 2002; 51(11): 952.

Daaleman TP, Frey BB. The Spirituality Index of Well-Being: A New Instrument for Health-Related Quality-of-Life Research. Annals of Family Medicine 2004;2:499–503.

Holland JC, Kash KM, Passik S, et al. A brief spiritual beliefs inventory for use in quality of life research in life-threatening illness. Psychooncology 1998;7:460–469.

Mohr S, Gillieron C, Borras L, Brandt PY, Huguelet P. The assessment of spirituality and religiousness in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 2007;195:247–253.

Ai AL, Tice TN, Peterson C, Huang B. Prayers, Spiritual Support, and Positive Attitudes in Coping With the September 11 National Crisis. J Pers 2005;73:763–791.

Hermann C. Development and testing of the spiritual needs inventory for patients near the end of life. Oncol Nurs Forum 2006;33:737–744.

Taylor EJ. Prevalence and associated factors of spiritual needs among patients with cancer and family caregivers. Oncol Nurs Forum 2006;33:729–735.

Yong J, Kim J, Han SS, Puchalski CM. Development and validation of a scale assessing spiritual needs for Korean patients with cancer. J Palliat Care 2008;24:240–246.

Büssing A, Balzat HJ, Heusser P. Spiritual needs of patients with chronic pain diseases and cancer—validation of the spiritual needs questionnaire. Eur J Med Res 2010;15:266–273.

Miller DK, Chibnall JT, Videen SD, Duckro PN. Supportive-Affective Group Experience for persons with life-threatening illness: reducing spiritual, psychological, and death-related distress in dying patients. J Palliat Med 2005;8:333–343.

Bormann JE, Smith TL, Becker S, et al. Efficacy of frequent mantram repetition on stress, quality of life, and spiritual well-being in veterans: a pilot study. Journal of Holistic Nursing 2005;23:395–414.

Rummans TA, Clark MM, Sloan JA et al. Impacting quality of life for patients with advanced cancer with a structured multidisciplinary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:635–642.

Kristeller JL, Rhodes M, Cripe LD, Sheets V. Oncologist Assisted Spiritual Intervention Study (OASIS): patient acceptability and initial evidence of effects. Int J Psychiatry Med 2005;35:329–347.

Schover LR, Jenkins R, Sui D, Adams JH, Marion MS, Jackson KE. Randomized trial of peer counseling on reproductive health in African American breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:1620–1626.

Brennan M, Heiser D. Introduction: Spiritual assessment and intervention: Current directions and applications. Journal of Religion, Spirituality and Aging 2004;17:1–20.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Online Appendix 1

(DOC 32 kb)

Online Appendix 2

(DOC 118 kb)

Online Appendix 3

(DOC 50 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Monod, S., Brennan, M., Rochat, E. et al. Instruments Measuring Spirituality in Clinical Research: A Systematic Review. J GEN INTERN MED 26, 1345–1357 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1769-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1769-7