Abstract

BACKGROUND

The contribution of masculinity to men’s healthcare use has gained increased public health interest; however, few studies have examined this association among African-American men, who delay healthcare more often, define masculinity differently, and report higher levels of medical mistrust than non-Hispanic White men.

OBJECTIVE

To examine associations between traditional masculinity norms, medical mistrust, and preventive health services delays.

DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS

A cross-sectional analysis using data from 610 African-American men age 20 and older recruited primarily from barbershops in the North, South, Midwest, and West regions of the U.S. (2003-2009).

MEASUREMENTS

Independent variables were endorsement of traditional masculinity norms around self-reliance, salience of traditional masculinity norms, and medical mistrust. Dependent variables were self-reported delays in three preventive health services: routine check-ups, blood pressure screenings, and cholesterol screenings. We controlled for socio-demography, healthcare access, and health status.

RESULTS

After final adjustment, men with a greater endorsement of traditional masculinity norms around self-reliance (OR: 0.77; 95% CI: 0.60–0.98) were significantly less likely to delay blood pressure screening. This relationship became non-significant when a longer BP screening delay interval was used. Higher levels of traditional masculinity identity salience were associated with a decreased likelihood of delaying cholesterol screening (OR: 0.62; 95% CI: 0.45–0.86). African-American men with higher medical mistrust were significantly more likely to delay routine check-ups (OR: 2.64; 95% CI: 1.34–5.20), blood pressure (OR: 3.03; 95% CI: 1.45–6.32), and cholesterol screenings (OR: 2.09; 95% CI: 1.03–4.23).

CONCLUSIONS

Contrary to previous research, higher traditional masculinity is associated with decreased delays in African-American men’s blood pressure and cholesterol screening. Routine check-up delays are more attributable to medical mistrust. Building on African-American men’s potential to frame preventive services utilization as a demonstration, as opposed to, denial of masculinity and implementing policies to reduce biases in healthcare delivery that increase mistrust, may be viable strategies to eliminate disparities in African-American male healthcare utilization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Among adults, men are least likely to use preventive health services,1–3 often delaying blood pressure (BP) and cholesterol screenings and routine check-ups, waiting longer after symptom onset before seeking care, and underutilizing clinically appropriate health services.2,4,5 How such underuse of preventive services impacts men’s health is not fully understood. Yet this underuse coincides with shorter life spans and more preventable deaths among men than women.

Compared to non-Hispanic White men, African-American men attend fewer preventive health visits, are less likely to know their cholesterol levels, have poorer BP control, and face greater morbidity and premature mortality from conditions amenable to early interventions.6–11 African-American men also experience earlier onset and higher death rates from heart disease8,12 and cancers detectable through screening,13,14 and often first present with conditions at more advanced stages.15,16 Recent data suggest the Black-White life-expectancy gap has narrowed,17 yet African-American men’s life-expectancy still lags behind non-Hispanic White women (11.3 years), African-American women (6.8 years), and non-Hispanic White men (6.2 years).18 Timely receipt of preventive health services may reduce this gap.

Studies of African-American men’s preventive health services utilization, primarily qualitative, attribute underutilization to fatalism,19 socioeconomic barriers,19,20 limited health knowledge or awareness,21 medical mistrust,22 and masculinity.20–23 Well-established healthcare utilization models suggest psychosocial factors work with socioeconomic and insurance-related determinants to produce such delays.24,25 The contribution of psychosocial factors is less understood. Quantitative analyses could illuminate these factors while informing development of culturally-relevant clinical and community-based interventions. We focused on two specific psychosocial factors relevant to African-American men’s preventive health services delays: masculinity and medical mistrust.

Previous research links masculinity to men’s mortality, health behavior, and healthcare use26–29 and medical mistrust to African-Americans' use of preventive health services.30,31 Researchers speculate that men delay using preventive health services because of traditional social constructions of masculinity, which prescribe extreme self-reliance, stoicism, and healthcare avoidance for men.27,32,33 Indeed, men who endorse more traditional masculine norms underutilize healthcare.26,29,34,35 Masculinity that manifests as “unmitigated agency” or extreme self-reliance is related to poor health behaviors,36 longer delays in seeking help for a heart attack,35 and noncompliance with physicians’ recommendations.35 Our study focuses on the contribution of traditional masculinity norms around self-reliance to African-American men’s preventive health services delays.

Men’s enactment of masculinity in a healthcare-seeking context varies according to their race and social location, since how men display masculinity depends on how much social power they hold.27 Theorists differ over how masculinity impacts African-American men’s healthcare use, largely because this group has experienced socioeconomic challenges (e.g., joblessness) to fulfilling traditional male provider role expectations37,38 and defines masculinity differently than non-Hispanic White men.39 Some argue that since African-American men hold relatively lower social positions, they may delay healthcare utilization to symbolically exercise masculine dominion over their bodies.27,40,41 Others posit that barriers to traditional male role fulfillment encourage African-American men to reject traditional masculinity, and adopt patterns of healthcare use that contradict dominant male behavioral norms.42–45

African-American men’s enactment of masculinity while seeking healthcare might also depend on how they prioritize traditional male norms. Theorists46 suggest that African-American men must attach a high degree of importance, or salience, to such norms before behavioral by-products of masculinity (i.e., healthcare seeking delays) manifest. Considering masculinity salience permits a more thorough assessment of African-American men’s commitment to traditional masculinity norms.47 Researchers rarely assess both the endorsement of masculinity norms and the degree of salience attributed to such norms. We address this oversight in the current study.

Empiric research on health care utilization in African-American men has been limited. Prior research has been in populations with limited diversity, treats masculinity as a stable personality or biological characteristic, and rarely considers potential contributions of race and masculinity.26,35 These constructs, moreover, should be yoked with the role of medical mistrust, which is higher among African-Americans,48 is linked to visible incidents of race-based medical malice towards this group (e.g., the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male),49 and is partly a consequence of traditional masculine beliefs.22,50 Strict interpretations of U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) screening guidelines51 and younger adults’ relatively healthy status have also led to a focus on preventive health services among middle-aged and older populations. This focus neglects emergent life-course perspectives52,53 and African-American men’s shorter lifespan and earlier onset of chronic conditions.12,54 Finally, nationally representative datasets rarely include measures assessing social constructions of masculinity and medical mistrust. Thus, we investigate the role of masculinity and medical mistrust in preventive health services delays among a community-based sample of African-American men.

METHODS

Study Population

This cross-sectional study of African-American men’s health and social lives was conducted in three waves from 2003-2009. Participants were recruited from seven barbershops in Michigan, Georgia, California, and North Carolina (80.7%) and from two academic institutions and events (19.3%): a community college in Southeastern Michigan, and a historically Black university (HBU) in central North Carolina. Fifty percent of the community college population was male and 22% were ethnic minorities. The HBU student population was 77% African-American and 33% male. The academic event was a 2003 conference for African-American male law enforcement professionals in Miami, FL.

Recruitment Procedure and Research Settings

Participants were recruited using fliers, direct contact, and by word-of-mouth. Barbershops were chosen as primary recruitment sites because they are trusted congregating spaces for African-American men from various socioeconomic backgrounds, and have been successfully targeted in interventions with this population.55,56 Eight barbershops characterized as “high volume” businesses (i.e., having a wait time of 30-60 minutes and serving a minimum of 30 customers per day) were approached about participation. “High volume” shops were preferred because men could use their wait time to complete the surveys. Initial contact with barbershop owners was made in person or by telephone and followed-up with a study brochure, copy of the survey, and consent forms, after which we obtained signed letters of support. One of eight barbershop owners declined to participate in the study. We solicited and incorporated feedback from barbers into our final survey. Receptionists and/or barbers invited patrons to participate in “a study about African-American men’s health”; men aged 18 or older and who self-identified as African-American were eligible to complete the survey. We limited our examination to men age 20 and older. Ninety percent of the men approached in the barbershops verbally consented to participate; most completed the survey during the wait time. The most frequently cited reason for non-participation was time constraints. All respondents received a $25 gift certificate for a free haircut. In academic settings, we used similar procedures to recruit in places of high congregation (e.g., student unions, cafeterias, conference exhibit halls); 86% of the men approached completed the survey and received a $25.00 gift card. The Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Preventive Health Services Delays

Preventive health services delays were assessed with three single-item questions: “About how long has it been since you had 1) a routine check-up by a doctor or a health professional; 2) your BP checked by a doctor or health professional; and 3) your blood cholesterol checked by a doctor or a health professional?” Response options were coded as follows (1 = Within the past year; 2 = Within the past two years; 3 = Within the past three years; 4 = Within the past five years; 5 = more than five years; 6 = never). Based on guidance from the USPSTF51 and previous studies,3,30,57 responses were dichotomized for each type of preventive health service (routine health visit, BP screening and blood cholesterol screening): 0 = No Delay (Receipt of in the past year for routine check-ups and BP screenings and in the past five years for cholesterol screenings) and 1 = Delay (All others).

Independent & Control Variables

Socio-demographic variables included age, education (≤High school, some college, and college/graduate or professional degree), marital status (currently married and unmarried), annual income (<$20,000, $20–39,999, ≥$40,000), and employment (employed full or part-time vs. unemployed). Healthcare access factors included health insurance (has health insurance vs. no health insurance) and usual source of care (has a usual source of care vs. no usual source of care). Physical health status was assessed with single-item questions; participants were asked to report whether they had ever been informed by a doctor or health professional that they had hypertension or coronary heart disease (Yes or No) and to rate their physical health on a scale ranging from 0 (“Poor”) to 5 (“Excellent”). We included a measure of depressive symptoms because of the positive association between psychological distress and preventive health services utilization.58–61 Healthcare visits may serve a “latent function” for psychologically distressed individuals, who may use the clinical interaction as an opportunity to make emotional disclosures.62 Depressive symptomatology was assessed with a 12-item version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D).63 The CES-D measures the frequency of depressive symptomatology, but is commonly used to assess acute mental health status. Responses ranging from 0 (“Rarely or none of the time”) to 3 (“Most or all of the time”) were summed to create an overall continuous score. Possible scores ranged from 0-36, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptomatology (Cronbach’s α = 0.79).

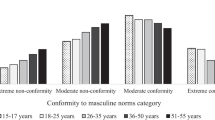

Masculinity was assessed with two scales. The Self-reliance subscale of the Male Role Norms Inventory (MRNI)64 is a 6-item measure that assesses traditional masculinity norms around autonomy and independent decision-making (e.g., “a man should never doubt his own judgment” and “a man must be able to make his own way in the world”). A mean score was computed from responses ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 7 (“strongly agree”) (Cronbach’s α = 0.71). We assessed the salience of traditional masculinity norms (e.g., having power and courage) to men’s overall identity with a 9-item scale constructed from previous qualitative work on masculinity meaning among African-American men.39 This measure assesses men’s commitment to traditional masculinity norms and their likelihood of invoking them when making behavioral choices.47,65 A mean score was computed from responses ranging from 1 (“not at all important”) to 5 (“extremely important”) (Cronbach’s α = 0.79). Medical mistrust was evaluated with the 14-item Medical Mistrust Index (MMI),48 which measures individual mistrust in healthcare organizations as a whole (e.g., “Healthcare organizations have sometimes done harmful experiments on their patients without their knowledge”). After reverse coding six items, a mean score was computed from responses ranging from 1 (“strongly disagree”) to 4 (“agree) (Cronbach’s α = 0.78). Higher scores in each of these scales indicate greater levels of that construct.

Analysis

We conducted simple bivariate analyses (χ2 and ANOVA) to describe our sample. We used logistic regression to calculate unadjusted odds ratios and 95% CI’s for the association between the sample characteristics and preventive health services delays (i.e., routine check-ups, BP screening, and cholesterol screening). Multiple logistic regression was used to examine adjusted associations between masculinity (Model 1), medical mistrust (Model 2), and preventive health services delays (routine check-up, BP screening, and cholesterol screening delays). We adjusted for socio-demographic, healthcare access, and health status factors, hypertension, coronary heart disease, and any heart disease diagnoses. For routine check-up and BP screening delays we also adjusted for asthma diagnosis. Model 3 examined simultaneous associations between masculinity, medical mistrust, and preventive health services delays. Multicollinearity was evaluated and found absent as evidenced by variance inflation factors (VIF) values of less than 5.66 We used the Hosmer Lemeshow test to evaluate the quality of our fully adjusted models and found good fit as indicated by non-significant statistics (P = 0.–7-0.51). We also computed pseudo-R2’s (Nagelkerke) to evaluate the quality of and variance explained by our models. Pseudo R2’s indicate full model fit at 1 and no fit at 0.

Since the appropriate interval of BP screening is unknown and screening every 2 years is recommended for those with BP < 120/180,51 we performed sensitivity analyses characterizing BP delays as “no BP screening within the past 2 years” to determine whether our multiple logistic regression results were affected by this different cut-point.

Data were missing for ≤ 5% of the variables except for usual source of care (missing for 5.7%), income (missing for 7.7%) and health insurance status (missing for 9.4%). Further analysis suggested that these values were missing at random. Hence, we used established multiple imputation procedures67 to generate five complete data sets. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals from these five data sets were examined independently and in aggregate. Since we did not observe any notable differences between values in our imputed and original data sets, we present results from the original data. All statistical analyses were performed with Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS for Windows, Release 17)68 and evaluated with two-tailed tests of significance using a 0.05 alpha level.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Participant ages ranged from 20–79 (M = 33.20, SD = 10.80). Most men were 30 and older (Table 1), were unmarried, resided in the south, worked at least part-time, and reported having health insurance. Participant incomes and education levels were equally distributed across the sample. Most men reported having a usual source of care, having “very good” self-rated health status, and no diagnosed hypertension or coronary heart disease. A higher percentage of men recruited from academic institutions were younger (in the 20–29 year-old age category) than those recruited from barbershops, were unmarried, reported completing some college, had incomes of < $20,000, and resided in the Midwest. These men had higher levels of depressive symptoms and more medical mistrust. More men recruited from barbershops reported hypertension and demonstrated higher levels of traditional masculinity identity salience, together with greater delays in routine check-ups (40.8%) and BP screenings (31.2%).

Unadjusted Associations between Sample Characteristics and Preventive Health Services Delays

In unadjusted models, youth, lower levels education and income, unmarried status, and having no usual source of care increased the likelihood of preventive health service delays. Younger men with lower incomes had a higher odds of reporting routine check-up, BP screening, and cholesterol screening delays (Table 2). Men who reported having “some college” or a “HS or less” education had a higher odds of reporting BP screening delays than men with a college, graduate, or professional degree. Unmarried men and those without a usual source of care had higher odds of delaying routine check-ups, BP, and cholesterol screenings. At the same time, the odds of delaying routine check-ups and BP screenings were lower among men residing in the South and higher among men recruited from academic institutions.

Results were mixed with regard to self-reported health status. Men with “very good” and “good” self-rated health status had a lower odds of delaying BP and cholesterol screenings than men who rated their health as “excellent.” Although men diagnosed with hypertension were less likely to delay BP and cholesterol screenings, the odds of such delays were higher among men reporting an asthma diagnosis. Higher depressive symptomatology and higher medical mistrust were associated with an increased odds of delaying routine check-ups and BP screenings. Greater masculine self-reliance was associated with reduced odds of delaying BP screenings.

Multivariate Associations Between Masculinity, Medical Mistrust, and Preventive Health Services Delays

Multivariate analyses indicated that when examined alone (Model 1), higher masculine self-reliance significantly reduced the odds of BP screening delays (P = 0.035). In this model, higher masculinity salience was also significantly associated with a reduced odds of delaying cholesterol screening (P = 0.006). Neither aspects of masculinity were significantly associated with routine check-up delays. Men with higher medical mistrust (Model 2) had significantly higher odds of reporting routine check-up (P = 0.005), BP screening (P = 0.005), and cholesterol screening delays (P = 0.032)(Table 3).

When the joint contribution of masculinity and medical mistrust were examined (Model 3), we observed a higher odds of routine check-up, BP and cholesterol screening delays among men with higher medical mistrust. Also, we found a lower odds of BP screening delays among men with higher masculine self-reliance, and a lower odds of cholesterol screening delays among men with higher masculinity salience. Nagelkerke pseudo-R2’s indicate that our fully adjusted models sufficiently explain a moderate percentage of the variance in routine check-up (37%), BP screening (33%), and cholesterol screening delays (27%).

Results from Sensitivity Analyses

Sensitivity analyses using “No BP screening in the past 2 years” as an indicator of BP screening delays revealed somewhat similar results. Overall, 17.7% of the sample reported not having a BP screening within the past 2 years. There were no differences in the percentage of participants recruited from barbershop and academic institution/events reporting no BP screening in the past 2 years. After adjustment for socio-demographic factors, recruitment site, comorbid conditions, and depressive symptomatology, the relationship between medical mistrust and BP screening delays was significant when examined alone (OR: 3.23; 95% CI: 1.34–7.78) and when masculinity was also included in the model (OR: 3.65; 95% CI: 1.47–9.04). The association between masculine self-reliance and BP screening delays was no longer significant when examined alone (OR: 0.95; 95% CI: 0.71–1.28) or when mistrust was also included in the model (OR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.67–1.23).

DISCUSSION

In a community-based sample of African-American men, we found that masculinity was associated with a reduced likelihood of delaying BP and cholesterol screening even after controlling for socio-demographics, healthcare access, and health status. Additionally, we demonstrated that medical mistrust rooted in expectations of racially biased treatment,22,48 not masculinity, may delay African-American men’s routine check-up initiation. While routine check-ups have debatable value in and of themselves,69 the USPSTF recognizes them as a “gateway” to more tailored preventive screening, behavioral health counseling, and disease detection.51 Forty-one percent of our sample delayed routine check-ups. Moreover, medical mistrust increased the likelihood of delaying BP and cholesterol screening in our sample, suggesting that medical mistrust may prevent a substantial number of African-American men from obtaining recommended services. Our findings augment existing research26,34 by demonstrating the complex impact of masculinity on African-American men’s health. Our apparently contradictory findings support the hypothesis that more marginalized social status results in an enactment of masculinity that manifests in attempts to acquire healthcare resources otherwise limited by socio-structural barriers. Also, African-American men’s move towards preventive healthcare when they endorse more traditional masculine norms may be attributed to distinct masculinity definitions, which prioritize pro-action and interdependence over relational distancing.39

We extend previous research linking medical mistrust to preventive health services30,31,70 by assessing the contributions of masculinity and medical mistrust to African-American men’s preventive health services use. Emergent life-course prevention perspectives,52,53 African-American men’s disproportionate risk for early-onset of chronic conditions,12,54 and support for the timely and increased utilization of preventive services71–75 heighten the relevance of our focus.

By measuring African-American men’s embrace of traditional masculinity norms (e.g., identity salience), we were also able to identify important distinctions in their contributions to this population’s use of these preventive health services. We observed a positive association between BP screening and men’s endorsement of traditional masculinity norms around self-reliance. Such norms, which emphasize agency, might empower African-American men to obtain BP screenings because they might perceive the general conditions (i.e., hypertension) revealed by the screenings as more normative and conducive to self-management. This association may be confounded by higher internal health locus of control, which is conceptually similar to self-reliance and has been found to increase health promotion engagement.76 The attenuation and apparent reversal of this effect during our sensitivity analyses implies that masculine self-reliance may become less helpful among men with longer BP screening delays. Future studies should examine the circumstances under which masculine self-reliance promotes and hinders BP screening.

We were intrigued to learn that cholesterol screening delays dipped only when traditional masculinity norms were more salient to African-American men’s identity. Timely uptake of this more invasive preventive service might require African-American men to iteratively weigh desires for self-directed preventive healthcare engagement against the need to protect oneself from potential medical harm or mistreatment. These hypotheses require further empirical evaluation but are consistent with ideas expressed elsewhere.22 Healthcare providers and public health professionals could leverage traditional masculine self-reliance in interventions and clinical encounters to empower African-American men to “seize control” of their health. This gendered, patient-centered approach could shift power balances, perhaps inspiring greater trust among African-American men.

Although depressive symptomatology was not a primary variable of interest, we did find that it was associated with reduced odds of delaying routine check-ups and BP screening in our unadjusted models. In the end, only the association between BP screening delays and depressive symptoms remained. This association may reflect African-American men’s greater likelihood of disengaging from healthcare in the face of psychological distress. African-American men may also be likely to rely on other coping strategies, thus diminishing the proposed latent psychological function of healthcare visits.62 Future studies should continue examining the role of depressive symptoms in African-American men’s healthcare use.

This study has limitations. The descriptive and cross-sectional design prevents us from making causal inferences. Our sample, although demographically similar to the U.S. population of African-American men, is not a nationally representative one.77,78 Although our data are self-reports, in post hoc sensitivity analyses, adjusted for social desirability,79 we found no differences in our logistic regressions. We improve on previous studies by assessing more than one aspect of masculinity and moving beyond its treatment as a fixed biological or personality characteristic. Given the multidimensional nature of masculinity, future studies should assess other aspects of the concept. Despite these limitations, our study advances a more nuanced understanding of how African-American men see preventive healthcare engagement as an opportunity to demonstrate their ability to “be a man about” their health.

References

Cherry DK, Woodwell DA, Rechtsteiner EA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2005 summary. Advance Data. 2007;2007:1–39.

Sandman D, Simantov E, An C, Fund C, Harris L. Out of touch: American men and the health care system. Commonwealth Fund New York, 2000.

Viera A, Thorpe J, Garrett J. Effects of sex, age, and visits on receipt of preventive healthcare services: a secondary analysis of national data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:15.

Neighbors HW, Howard CS. Sex differences in professional help seeking among adult Black Americans. Am J Community Psychol. 1987;15:403–17.

Green CA, Pope CR. Gender, psychosocial factors and the use of medical services: a longitudinal analysis. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:1363–72.

United States. Agency for Healthcare R, Quality. National healthcare disparities report. In: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2006. Rockville: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Service; 2006.

Arias E. United states life tables, 2004. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2007;56:1–39.

Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2006 Update: A report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2006;113:e85–151.

Wong MD, Chung AK, Boscardin JW, et al. The contribution of specific causes of death to sex differences in mortality. Public Health Rep. 2006;121:746–54.

Hertz RP, Unger AN, Cornell JA, Saunders E. Racial disparities in hypertension prevalence, awareness, and management. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2098–104.

Nelson K, Norris K, Mangione CM. Disparities in the diagnosis and pharmacologic treatment of high serum cholesterol by race and ethnicity: data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:929–35.

Barnett E, Casper MC, Halveron TA, et al. Men and heart disease an atlas of racial and ethnic disparities in mortality. Morgantown: Office for Social Environment and Health Research, West Virginia University; 2000.

American Cancer Society. Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures 2008-2010. In: Society AC, ed. Atlanta, 2008.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2009-2010. In: Society AC, ed. Atlanta, 2009.

Agrawal S, Bhupinderjit A, Bhutani MS, et al. Colorectal cancer in African Americans. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:515–23.

Ndubuisi SC, Kofie VY, Andoh JY, Schwartz EM. Black-White differences in the stage at presentation of prostate cancer in the District of Columbia. Urology. 1995;46:71–7.

Harper S, Lynch J, Burris S, Davey Smith G. Trends in the black-white life expectancy gap in the United States, 1983-2003. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;297:1224–32.

Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu J, Murphy SL. Deaths: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2008;56:1–120.

Ravenell JE, Whitaker EE, Johnson WE Jr. According to him: barriers to healthcare among African-American men. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100:1153–60.

Whitley EM, Samuels BA, Wright RA, Everhart RM. Identification of barriers to healthcare access for underserved men in Denver. J Mens Health Gend. 2005;2:421–8.

Cheatham CT, Barksdale DJ, Rodgers SG. Barriers to health care and health-seeking behaviors faced by Black men. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2008;20:555–62.

Hammond WP, Matthews D, Corbie-Smith G. Psychosocial factors associated with routine health examination scheduling and receipt among African-American men. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102:276–289.

Wade JC. Masculinity ideology, male reference group identity dependence, and African American men's health-related attitudes and behaviors. Psychol Men Masc. 2008;9:5–16.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10.

Bradley EH, McGraw SA, Curry L, et al. Expanding the Andersen model: the role of psychosocial factors in long-term care use. Health Serv Res. 2002;37:1221–42.

Mahalik JR, Burns SM, Syzdek M. Masculinity and perceived normative health behaviors as predictors of men's health behaviors. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:2201–9.

Courtenay WH. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men's well-being: A theory of gender and health. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:1385–401.

Månsdotter A, Lundin A, Falkstedt D, Hemmingsson T. The association between masculinity rank and mortality patterns: a prospective study based on the Swedish 1969 conscript cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:408–13.

Marcell AV, Ford CA, Pleck JH, Sonenstein FL. Masculine beliefs, parental communication, and male adolescents' health care use. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e966–75.

Musa D, Schulz R, Harris R, Silverman M, Thomas SB. Trust in the health care system and the use of preventive health services by older Black and White adults. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1293–9.

O'Malley AS, Sheppard VB, Schwartz M, Mandelblatt J. The role of trust in use of preventive services among low-income African-American women. Prev Med. 2004;38:777–85.

Addis ME, Mahalik JR. Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. Am Psychol. 2003;58:5–14.

Helgeson VS. Relation of agency and communion to well-being: Evidence and potential explanations. Psychol Bull. 1994;116:412–28.

Mahalik JR, Lagan HD, Morrison JA. Health behaviors and masculinity in Kenyan and U.S. male college students. Psychol Men Masc. 2006;7:191–202.

Helgeson VS. The role of masculinity in a prognostic predictor of heart attack severity. Sex Roles. 1990;22:755–74.

Helgeson V, Fritz H. Unmitigated agency and unmitigated communion: Distinctions from agency and communion. J Res Pers. 1999;33:131–58.

Bound J, Freeman RB. What Went Wrong? The erosion of relative earnings and employment among young Black men in the 1980s. Q J Econ. 1992;107:201–32.

Holzer HJ, Offner P. Trends in employment outcomes of young black men, 1979-2000. Madison: Institute for Research on Poverty, University of Wisconsin--Madison; 2002.

Hammond WP, Mattis JS. Being a man about It: Manhood meaning among African American men. Psychol Men Masc. 2005;6:114–26.

Wallace M. Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman. Verso, 1999.

Staples R. Black masculinity: The Black male's role in American society. Feminism and Masculinities. 2004:121.

Abreu J, Goodyear R, Campos A, Newcomb M. Ethnic belonging and traditional masculinity ideology among African Americans, European Americans, and Latinos. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 2000;1:75–86.

Gordon E. Cultural politics of black masculinity. Transforming Anthropology. 1997;6:36–53.

Aronson RE, Whitehead TL, Baber WL. Challenges to masculine transformation among urban low-income African American males. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:732–41.

Wade JC, Brittan-Powell C. Men's attitudes toward race and gender equity: The importance of masculinity ideology, gender-related traits, and reference group identity dependence. Psychol Men Masc. 2001;2:42–50.

Sheldon S, Serpe RT. Identity salience and psychological centrality: equivalent, overlapping, or complementary concepts? Social Psychology Quarterly. 1994;57:16–35.

Hogg MA, Terry DJ, White KM. A tale of two theories: A critical comparison of identity theory with social identity theory. Soc Psychol Q. 1995;58:255–69.

LaVeist T, Nickerson K, Bowie J. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57:146–61.

Gamble VN. Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and health care. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1773–8.

Hammond WP. Psychosocial correlates of medical mistrust among African American men. Am J Community Psychol. 2010;45:86–107.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008.

Vasan RS, Kannel WB. Strategies for cardiovascular risk assessment and prevention over the life course: Progress amid imperfections. Circulation. 2009;120:360–3.

Lynch J, Smith GD. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology. Annu Rev Pub Health. 2005;26:1–35.

Fields LE, Burt VL, Cutler JA, Hughes J, Roccella EJ, Sorlie P. The burden of adult hypertension in the United States 1999 to 2000: A rising tide. Hypertension. 2004;44:398–404.

Hess PL, Reingold JS, Jones J, et al. Barbershops as hypertension detection, referral, and follow-up centers for Black men. Hypertension. 2007;49:1040–6.

Hart A, Bowen DJ. The feasibility of partnering with African-American barbershops to provide prostate cancer education. Ethn Dis. 2004;14:269–73.

Corbie-Smith G, Flagg E, Doyle J, O’Brien M. Influence of usual source of care on differences by race/ethnicity in receipt of preventive services. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:458–64.

Witt W, Kahn R, Fortuna L, et al. Psychological Distress as a Barrier to Preventive Healthcare Among U.S. Women. J Prim Prev. 2009;30:531–47.

Tessler R, Mechanic D, Dimond M. The effect of psychological distress on physician utilization: A prospective study. J Health Soc Behav. 1976;17:353–64.

Bellon JA, Delgado A, Luna JD, Lardelli P. Psychosocial and health belief variables associated with frequent attendance in primary care. Psychol Med. 1999;29:1347–57.

Manning WG Jr, Wells KB. The effects of psychological distress and psychological well-being on use of medical services. Med Care. 1992;30:541–53.

Shuval JT. Social functions of medical practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1970.

Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401.

Levant RF, Hirsch LS, Celentano E, Cozza TM. The male role: An investigation of contemporary norms. Journal of Mental Health Counseling. 1992;14:325–37.

Sheldon S, Serpe RT. Identity salience and psychological centrality: equivalent, overlapping, or complementary concepts? Soc Psychol Q. 1994;57:16–35.

Hair JF. Multivariate Data Analysis. Upper Saddle River, N.J.; Harlow: Pearson Education, 2009.

Allison PD. Multiple imputation for missing data: A cautionary tale. Sociol Methods Res. 2000;28:301–9.

SPSS 17 for Windows. Chicago, Ill.: SPSS Inc., 2008.

Boulware LE, Marinopoulos S, Phillips KA, et al. Systematic Review: Systematic review: The value of the periodic health evaluation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:289–300.

Fiscella K, Franks P, Clancy CM. Skepticism toward medical care and health care utilization. Med Care. 1998;36:180–9.

Elster AB, Levenberg P. Integrating comprehensive adolescent preventive services into routine medicine care. Rationale and approaches. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1997;44:1365–77.

Marcell AV. The adolescent male. In: Heidelbaugh JJ, Jauniaux E, Landon MB, eds. Clinical men's health: evidence in practice. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier; 2007:75–94.

Rich JA. Primary care for young African American men. J Am Coll Health. 2001;49:183.

Park MJ, Paul Mulye T, Adams SH, Brindis CD, Irwin JCE. The health status of young adults in the United States J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:305–17.

Stamler J, Daviglus ML, Garside DB, Dyer AR, Greenland P, Neaton JD. Relationship of baseline serum cholesterol levels in 3 large cohorts of younger men to long-term coronary, cardiovascular, and all-cause mortality and to longevity. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;284:311–8.

Wallston K, Wallston B. Who is responsible for your health? The construct of health locus of control. In: Sanders GS, Suls JM, eds. Social psychology of health and illness. Hillsdale: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1982:65–95.

United States Census Bureau. United States - Data Sets - American Fact Finder. 2009.

United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. The employment situation: December 2004-2007. Washington: U.S. Dept. of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2008.

Reynolds WM. Development of reliable and valid short forms of the Marlowe-Crowne social desirability scale. J Clin Psychol. 1982;38:119–25.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was supported by a Student Award Program award to the first author from the Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation (Grant # 657.SAP), The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health & Society Scholars Program, and The University of North Carolina Cancer Research Fund. Additional research and salary support during the preparation of this manuscript was provided to the first author from the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities (Award # 1L60MD002605-01), and National Cancer Institute (Grant # 3U01CA114629-04 S2).

Additional Contributions

The first author wishes to thank faculty, student, and community members of the UNC Men’s Health Research Lab: Yasmin Cole-Lewis, Travis Melvin, Justin Smith, Allison Mathews, Dr. Keon Gilbert, Melvin R. Muhammad, and Donald Parker for their assistance with data collection for the African-American Men’s Health & Social Life Study. The first author also thanks Dr. Amani Nuru-Jeter, Keith Hermanstyne, Adebiyi Adesina, and Michael Hammond for their assistance with data collection. The authors thank Dr. Nestor Lopez-Duran for his feedback about the statistical analyses.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hammond, W.P., Matthews, D., Mohottige, D. et al. Masculinity, Medical Mistrust, and Preventive Health Services Delays Among Community-Dwelling African-American Men. J GEN INTERN MED 25, 1300–1308 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1481-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1481-z