Abstract

BACKGROUND

Diagnostic and treatment delay in depression are due to physician and patient factors. Patients vary in awareness of their depressive symptoms and ability to bring depression-related concerns to medical attention.

OBJECTIVE

To inform interventions to improve recognition and management of depression in primary care by understanding patients’ inner experiences prior to and during the process of seeking treatment.

DESIGN

Focus groups, analyzed qualitatively.

PARTICIPANTS

One hundred and sixteen adults (79% response) with personal or vicarious history of depression in Rochester NY, Austin TX and Sacramento CA. Neighborhood recruitment strategies achieved sociodemographic diversity.

APPROACH

Open-ended questions developed by a multidisciplinary team and refined in three pilot focus groups explored participants’ “lived experiences” of depression, depression-related beliefs, influences of significant others, and facilitators and barriers to care-seeking. Then, 12 focus groups stratified by gender and income were conducted, audio-recorded, and analyzed qualitatively using coding/editing methods.

MAIN RESULTS

Participants described three stages leading to engaging in care for depression — “knowing” (recognizing that something was wrong), “naming” (finding words to describe their distress) and “explaining” (seeking meaningful attributions). “Knowing” is influenced by patient personality and social attitudes. “Naming” is affected by incongruity between the personal experience of depression and its narrow clinical conceptualizations, colloquial use of the word depression, and stigma. “Explaining” is influenced by the media, socialization processes and social relations. Physical/medical explanations can appear to facilitate care-seeking, but may also have detrimental consequences. Other explanations (characterological, situational) are common, and can serve to either enhance or reduce blame of oneself or others.

CONCLUSIONS

To improve recognition of depression, primary care physicians should be alert to patients’ ill-defined distress and heterogeneous symptoms, help patients name their distress, and promote explanations that comport with patients’ lived experience, reduce blame and stigma, and facilitate care-seeking.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

When patients explicitly request help for depression, primary care physicians (PCPs) generally initiate guideline-concordant care, including medication, referral for psychotherapy or appropriate follow-up.1 However, not all people request help for depressive symptoms — and physicians often do not recognize patients’ emotional distress2–4 — which might explain why one-fourth of people with major depression are undiagnosed5 and fewer than half receive treatment.6,7

A critical but poorly understood step in depression care involves symptom recognition and disclosure. Even people who desire treatment may be unwilling or unable to disclose their depressive symptoms to physicians.8 Patient-level barriers to disclosure include lack of knowledge (about the symptoms or treatment), socio-cultural factors (e.g. stigmatization,9–11 beliefs about help-seeking), psychological factors (e.g. difficulty articulating emotions), discomfort discussing personal issues,12 and the belief that physicians are not interested in or not able to treat depression.13

Discordance between physician and patient beliefs may also hinder depression care.14–20 When patients attribute depressive symptoms to problems of living or physical illness,14–16,21,22 physicians are more likely to overlook depression and pursue situational explanations or organic disease.18,19 Unwillingness to seek care may result from discordance between patients’ treatment preferences (generally, psychosocial interventions) and their expectations about what their physicians will recommend (generally, medications).20

To gain a deeper understanding of how people recognize their own depressive symptoms and bring them to the attention of their PCPs, we used focus groups to explore cognitive, relationship, and communication factors that affected recognition and disclosure of depressive symptoms.

METHODS

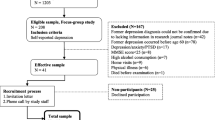

Focus groups were conducted with a diverse sample of people with personal and vicarious experience with depression; results from these groups informed the design of targeted and tailored media interventions to encourage depression care-seeking in primary care.

Study Sites & Participants

The institutional review boards at the three study sites (Rochester, New York; Austin, Texas; and Sacramento, California) approved the protocol. We purposively sampled participants to achieve maximum variation and representativeness by income, gender, and racial/ethnic background. In addition to on-line postings, we sent postcards, and posted flyers in public venues in Zip codes that reported median incomes closest to the 50th (middle-income) and 15th (low-income) percentiles.

Study participants were English-speaking men and women, aged 25–64, who reported a personal history of depression or experience with a close friend or relative with depression. Each participant received $35.

Data Collection

The team developed an initial set of guiding questions, based on theories of illness cognition,14–16,23–26 and behavior change (e.g. transtheoretical model, social cognitive theory),27–30 and research on depression care-seeking.111 These approaches propose that people are most likely to seek treatment if they are well-informed and psychologically minded, experience typical symptoms of depression and little stigma, and have confidence in the effectiveness of treatment, few concerns about side effects, adequate social support, and high self-efficacy. Open-ended questions prompted participants to disclose their “lived experiences” of depression, depression-related knowledge and beliefs, and facilitators and barriers to care-seeking. The questions had a pragmatic goal — to help design media interventions for those in pre-contemplative and contemplative stages of care-seeking starting with the initial experience of symptoms continuing through treatment.

Before each focus group, participants provided informed consent, and completed a questionnaire. Groups lasted 75–110 minutes, and were facilitated by 1–2 study investigators. A project coordinator took notes.

Based on pilot focus groups (balanced for gender and income) conducted at each site, we expanded our guiding questions to explore two areas: the time between the appearance of depressive symptoms and the first realization that something might be wrong, and the interactions among people with depressive symptoms, their close social contacts, and the health care system that influenced care-seeking (see Appendix).31,32 Using the revised guiding questions, we conducted four additional focus groups per site, stratified by gender and income level (“low”, “middle”), in early 2008.

Data Analysis

Groups were digitally recorded, then transcribed. First, the entire multidisciplinary study team identified broad emergent coding categories based on iterative line-by-line review of 15 focus group transcripts. The codes were grouped into larger categories by consensus during regular meetings. Then, the primary coding team (DAP & CSC) reviewed the transcripts for accuracy while listening to the recordings and systematically coded all 15 transcripts using EthnoNotes software; they selected numerous illustrative quotes and identified each quote according to city, gender, and income group.

In the second phase, the data analysis team (RME, PRD, PB, JDB) refined codes pertaining to cognitive and communicative processes that hindered or enabled discussion of depression-related symptoms. They rechecked the transcripts, reviewed the codes and coded transcripts, refined definitions of the codes, defined sub-codes, searched for recurrent themes, generated hypotheses, and extracted representative quotes from the initial set that exemplified each sub-code. The team organized relevant codes and transcript segments into three themes (Table 1) and explored theoretical links among the codes and themes. Disconfirming data were used to modify themes and refine hypotheses. Co-investigators not involved in the initial phases of the analysis audited the results for consistency, clarity, and comprehensiveness (MPF, ABR, RLK). Data relating to gender, social and patient-physician relationship issues are reported elsewhere.33,34

RESULTS

Study Participants

One hundred eighty-three people responded to our recruitment efforts; 37 were unavailable or ineligible due to age or income. Among the 146 remaining volunteers, we were able to accommodate 116 (79%) participants into one of 15 scheduled focus groups (Table 2).

Naming, Knowing and Explaining

Participants described three linked themes: their inner experiences of depression as they first recognized that something was wrong (“knowing”), sought to put a name on their distress (“naming”) and tried to make sense of their experiences (“explaining”) (Table 1).

Knowing

We first examined how people became aware that their experience of “depression” might represent something abnormal or undesirable (Text Box 1)

Not knowing

Many participants reported not knowing that something was wrong — sometimes for years. One participant did not seek treatment because they “didn’t know there was anything wrong with me…” Another was “totally unaware” but, in retrospect could “pinpoint times even as a teenager that I obviously isolated myself.” Some were equally unaware, despite having had prior treatment for depression.

Several participants described how personality can influence knowing. Some who described themselves as “always dark,” “introspective”, and “always in a bad mood” had been so acclimated to being “gloomy” that it was difficult for them to appreciate their descent into depression. In contrast, self-described extraverts, unaccustomed to introspection or negative emotions, were not attuned to the nuances of their moods. They had difficulty reconciling a self-image as an “outgoing likeable person” with the experience of depression. Traits also made it more difficult for participants’ family members and friends to know they were depressed.

Becoming aware

A surprisingly wide range of emotional and behavioral changes, physical symptoms, and perceptual distortions cued participants that something was wrong. Some described a “growing awareness;” others described sentinel events — hospitalization for substance abuse or “feeling totally out of control.” Many reported delays in seeking care, especially lower-income men. By normalizing their symptoms as “everyday life problems that many other people are going through” they delayed until their distress was extreme before seeking help.

Social influences

Family members, friends or health professionals “pushed” some participants towards knowing. Others reported the opposite –friends and family seemed unable to notice or discuss depression, even suicidal statements. One man commented, “…you’re not looking for help and … there are people around that aren't recognizing it either.” Spending time with someone in the midst of depression did not facilitate recognition of depression in oneself; some individuals perceived their own distress as categorically distinct from the clinical depression of their friends or loved ones.

Naming

Once having recognized that something was “not right,” participants described difficulty naming their distress. Below, we discuss four aspects of naming (Text Box 2).

The lived experience

Women, especially mid-income women, described more aspects of the depression experience than men. Participants’ experiences included symptoms (e.g., mood, interest, appetite, sleep, energy, slowing) typically considered to be diagnostic criteria for depression,35 as well as other domains: perceptual distortion, metaphors of constriction and social inhibition. Commonly, participants felt as if there were actually “haze,” “fog” or “shadows” that affected their ability to see clearly. They used metaphors, most commonly of enclosed spaces with no way out. One woman suggested that depression was “the monster” that “you can’t see” but “all of a sudden they put a name on it,” allowing it to “be fixed with …a pill or something.” Social inhibition was manifested by not answering the phone, not going out, not shaving, or making sarcastic or negative comments in social situations. Because patients did not name these experiences as “depression”, “[…asking], ‘Have you ever had depression?,’ probably isn’t the best [question] to use, because if you aren’t recognizing it at this point, you can say, ‘no.’”

Clinical and colloquial use of word “depression”

Participants commented that the words “depressing,” “depressed”, and “depression,” are used colloquially (“So depressing that they didn’t win”), as a personality characteristic (“He’s always down and depressed”) and as a clinical name for an illness (“I am being treated for depression”). In addition, some participants’ narrow concept of depression interfered with recognition and acceptance of the diagnosis. In one focus group, mid-income women expressed confusion about why only one word, “depression,” was used to describe such diverse experiences, time courses, and treated disorders.

The value of naming

Despite the problems with the word “depression”, participants did not dispute the value of naming their distress. Because they saw depression as “beyond sad,” participants searched for qualifiers to capture the differences between depression and ordinary sadness– it “spirals down,” “lasts longer,” and is “ “deeper,” “more painful,” and “irrational”. One low-income woman reflected a common perspective that “depression is more of a medical thing, where sadness could be, maybe, from tragedy.” Depression often involved “lacking control” over one’s own thinking.

Participants remarked that they often avoided the word “depression” with friends, family, and employers -- to avoid misunderstanding, stigmatization or over-burdening others. One low-income woman said, “…if I tell my family….I would say that I’m sad or I’m tired. I don’t say I’m depressed.” Many participants reported that a diagnosis of “depression” had a paradoxical result on their recovery. On the one hand, naming distress as “depression” led to improved access to medical treatment. Conversely, participants feared losing the very social support that could help them overcome depression — friends and family might avoid or blame them, and they might experience employment discrimination.

Questionnaires

Completing a depression questionnaire played an important legitimizing and exculpating role for several participants; it helped attach words to experience, convince them of the gravity of the situation, that it was “real….not just in (their) head(s)”. One mid-income male participant noted that he used to “associate” depression with “crying, sadness…inability to kind of cope and…and get on with life” but that “didn’t describe (his) situation at all.” However, once he “sat down and …faced that questionnaire,” he realized that he was suffering from depression, despite his ability to “bring home a paycheck.” While men generally reported positive reactions to depression screening questionnaires, several women objected to the checklist quality of the questionnaires preferring a more personal approach.

Explaining

Finding meaningful causal explanations for their distress allowed participants to organize their experience and engage with health care professionals. Three types of explanations were identified: physical, characterological, and situational (Text Box 3). Most favored a single explanation, but some combined two or more types of explanations into a coherent narrative; more often, the link between the two (or more) explanations was not made. A few participants commented that they could find no meaningful explanation for their distress.

Physical explanations

Physical explanations — depression as a “medical condition,” “disease,” or “illness” — were welcomed by those who initially had explanations that involved self-blame. Often, physical explanations were offered by health care professionals, family members, celebrities or advertisements, which the patient then adopted. Participants typically referred to “chemicals” being “imbalanced” or “blocked.” Others attributed depression to menopause, or lack of sexual vigor (“my mojo is gone…”). Whereas “chemical imbalance” typically reduced stigma and blame, genetic attributions left a more complex wake, which involved blame ascribed to a prior generation and to themselves for their role in transmission to future generations.

Characterological explanations

Participants who felt that depression was “just part of me” or “I’ve been depressed since I was born” had more difficulty recognizing that they had a condition that needed treatment. They viewed their propensity to depression as a personal weakness, lower self-worth and a “shameful” lack of control. Participants who used the term “depressed” to describe a personality characteristic (rather than a treatable clinical condition) seemed less likely to seek care.

Situational explanations

When depression was also viewed as a result of current stressors (e.g., accidents, deaths, family conflict) and past events, participants felt that social factors were to blame for their distress and that changing the social environment would be necessary to alleviate depressive symptoms. Often “several things… jumped on you at one time;” many were woven into life’s daily fabric — “wear[ing] yourself out taking care of everybody else” and “not being able to let go of a relationship.” One participant noted that “people or situations…have a negative effect on you” and one would be well-advised “to stay away from [these] influences.” Participants also referred to childhood trauma and neglect (e.g., insufficient “lap time”), and parental divorce, substance abuse and mental illness. One man attributed depression to conflicts between his emerging sexual orientation and his family’s religious beliefs. Others noted secretiveness of their early emotional environment leading to self-silencing and internalizing their distress.

DISCUSSION

Our demographically and geographically diverse participants described three themes relevant to presenting depression-related symptoms to primary care physicians and engaging in care — “knowing,” “naming”, and “explaining.” Our findings also suggest ways in which theories of diagnostic delay, illness cognition and health behavior change can inform interventions to improve depression care.25,28,29,36

Whereas research on diagnostic and treatment delay tends to emphasize physician factors (such as misattribution), our findings underscore the importance of patient-related delay.25,36 For example, “not-knowing” can be seen as a type of appraisal delay. While “knowing” can promote care-seeking, sometimes patients come to “know” that something is awry during discussions with physicians about experiences that initially seem unrelated to depression, such as pain, fatigue, and a vague sense of “just not feeling right.”

“Naming” refers to how people find words to describe their distress. “Naming” is often a precondition for the contemplation phase of behavior change; conversely, not naming one’s distress as depression can contribute to “illness delay” — the temporal gap between deciding one is ill and seeking care. Many participants had difficulty naming their distress as depression because their experiences did not comport with their “common-sense” models of depression.24 Nor were many of these experiences likely to have been considered depression symptoms by their physicians, who held different but narrow models that did not encompass the protean ways in which people experience depression. Expanding the public’s concept of depression and physicians’ ability to accommodate diverse experiences of depression may facilitate dialogues between patients and physicians and lead to earlier recognition.

The word “depression”– with its colloquial connotations and associations with immutable personality characteristics — presented multiple subtle issues. Participants found it less stigmatizing to say “I have depression” rather than “I am depressed,” just as men might refer to having erectile dysfunction rather than being impotent. Based on prior reports, we thought that older patients, Blacks, Latinos, and Asians would have more difficulty naming their distress as “depression;”37 we found that naming was problematic for everyone. Standardized depression screening tools,38 helped many “name” their depression, but some women found them unhelpful.

Meaningful explanations, our third theme, were strongly influenced by social relationships patients have with health care professionals, friend and family, and by the media.31 Arriving at an understanding of depression that comports with personal illness beliefs, exculpates (“not my fault’), instills hope (“treatment can work”), and empowers (“I can do it”] can promote movement from contemplation to action.23–25,27–30 But, not all explanations propel people along the path to care. The most motivating and destigmatizing explanations represented a balance between physical, characterological and situational attributions. While most participants ultimately preferred physical (e.g. chemical imbalance) to characterological attributions, they often recognized that “chemical imbalances” neglected the uniquely personal aspects of the depression experience — and devalued behavioral or psychosocial treatment options. Furthermore, participants felt that personality traits and social forces were important to consider in promoting recognition of depression. However, holding predominantly situational attributions, while defusing self-blame, often resulted in beliefs that changes in the social environment — not medical care — were necessary to improve their mood, functioning, and self-concept.

Our observations are relevant to both patient-physician communication and the development of clinical, public health, and media interventions to improve depression care. First, depression-related information should emphasize the diverse ways in which people experience depression. Second, common difficulties with the word “depression” should be addressed. Third, explanations for emotional distress should take into account individual vulnerability — due to personality, situational, social, and genetic factors — while being careful to avoid blame and emphasizing responsiveness to treatment. Fourth, physicians should not rely on symptom checklists exclusively to detect depression. Finally, discussions of depression-related concerns with PCPs should not require that the patient endorse a self-diagnosis of depression.

Several limitations should be noted. First, self-selected volunteers from urban areas — with prior psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy — present different views than undiagnosed people with depression presenting in primary care. Second, depression diagnoses were by self-report. Finally, focus groups cannot explore themes in as much depth as individual interviews and can foster collective thinking which reinforces some themes and avoids others.

CONCLUSIONS

A framework that considers the role of health systems, illness cognition, behavior change, and social influences can advance our understanding of how people come to know, name, and explain their depressive symptoms and seek care. To bring depressive symptoms to the attention of physicians, people must first become aware that their ill-defined, heterogeneous and (often) longstanding distress is not normal and warrants attention. While labeling their experience as “depression” is often helpful, in order to seek care, people also need meaningful explanations for their distress that comport with their lived experience, reduce blame, stigma, and shame and provide hope that interventions will help. Physicians, families, friends, and the media can prompt people who have depressive symptoms to seek care by adopting a multi-faceted understanding of the experience of depression from the patient’s perspective — and helping them find the words to bring their experiences and concerns to the attention of physician. In that way, a shared vision of the cause and treatment of depression can facilitate follow-through with a mutually-endorsed plan.

References

Kravitz RL, Epstein RM, Feldman MD, et al. Influence of patients' requests for direct-to-consumer advertised antidepressants: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:1995–2002.

Levinson W, Gorawara-Bhat R, Lamb J. A study of patient clues and physician responses in primary care and surgical settings. JAMA. 2000;284:1021–7.

Lang F, Floyd MR, Beine KL. Clues to patients' explanations and concerns about their illnesses. A call for active listening. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:222–7.

Epstein RM, Hadee T, Carroll J, Meldrum SC, Lardner J, Shields CG. "Could this be something serious?" Physicians' responses to patients' expressions of worry and distress. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1731–9.

Barbui C, Tansella M. Identification and management of depression in primary care settings. A meta-review of evidence. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2006;15:276–83.

Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:55–61.

Harman JS, Edlund MJ, Fortney JC. Disparities in the adequacy of depression treatment in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:1379–85.

Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, Wells KB. Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:527–34.

Barney LJ, Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF. Exploring the nature of stigmatising beliefs about depression and help-seeking: implications for reducing stigma. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:61.

Goldman LS, Nielsen NH, Champion HC. Awareness, diagnosis, and treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:569–80.

Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Jenckes MW, Gonzales JJ, Levine DM, Ford DE. Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:431–8.

Mohr DC, Hart SL, Howard I, et al. Barriers to psychotherapy among depressed and nondepressed primary care patients. Ann Behav Med. 2006;32:254–8.

Kravitz RL, Paterniti DA, Epstein R, et al. Organizational and relational barriers to depression help-seeking in primary care: Qualitative Study. Ann Fam Med. 2009.

Karasz A, Sacajiu G, Garcia N. Conceptual models of psychological distress among low-income patients in an inner-city primary care clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:475–7.

Karasz A, Watkins L. Conceptual models of treatment in depressed Hispanic patients. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4:527–33.

Karasz A. Cultural differences in conceptual models of depression. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1625–35.

Feldman MD, Franks P, Duberstein PR, Vannoy S, Epstein R, Kravitz RL. Let's not talk about it: suicide inquiry in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:412–8.

Rudebeck CE. General practice and the dialogue of clinical practice: On symptoms, symptom presentations, and bodily empathy. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1992;Supplement:1–87.

Epstein RM, Quill TE, McWhinney IR. Somatization reconsidered: Incorporating the patient's experience of illness. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:215–22.

Raue PJ, Schulberg HC, Heo M, Klimstra S, Bruce ML. Patients' depression treatment preferences and initiation, adherence, and outcome: a randomized primary care study. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:337–43.

Good BJ, Good MD. The Meaning of Symptoms: A Cultural Hermeneutic Model for Clinical Practice. In: Eisenberg L, Kleinman A, eds. The Relevance of Social Science for Medicine. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Co.; 1981:165–96.

Stoeckle JD, Barsky AJ. Attributions: Uses of Social Science Knowledge in the 'Doctoring' of Primary Care. In: Eisenberg L, Kleinman A, eds. The Relevance of Social Science for Medicine. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Co.; 1981:223–40.

Baumann LJ, Cameron LD, Zimmerman RS, Leventhal H. Illness representations and matching labels with symptoms. Health Psychol. 1989;8:449–69.

Leventhal H, Diefenbach MA, Leventhal EA. Illness cognition: Using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cogn Ther Res. 1992;16(2):143–63.

Safer MA, Tharps QJ, Jackson TC, Leventhal H. Determinants of three stages of delay in seeking care at a medical clinic. Med Care. 1979;17:11–29.

Karasz A. The development of valid subtypes for depression in primary care settings: a preliminary study using an explanatory model approach. J of Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196:289–96.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:390–5.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy Theory, Research and Practice. 1982;19:276–88.

Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK. Linking theory, research, and practice. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1997:19–35.

Pescosolido BA. Beyond rational choice: The social dynamics of how people seek help. Am J Sociol. 1992;97:1096.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10.

Rochlen AB, Paterniti DA, Epstein RM, Duberstein P, Willeford L, Kravitz RL. Barriers in Diagnosing and Treating Men With Depression: A Focus Group Report. Am J Mens Health. 2009.

Bell RA, Paterniti DA, Azari R, et al. Encouraging patients with depressive symptoms to seek care: A mixed methods approach to message development. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:198–205.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

Andersen R, Anderson OW, Smedby B. Perception of and response to symptoms of illness in Sweden and the United States. Med Care. 1968;6:18–30.

Wittink MN, Dahlberg B, Biruk C, Barg FK. How older adults combine medical and experiential notions of depression. Qual Health Res. 2008;18:1174–83.

Lowe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, Grafe K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). J Affect Disorders. 2004;81:61–6.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded with support from Grants # R01MH79387 and K24MH72756 (R. Kravitz, PI) and K24MH072712 (P. Duberstein, PI). The authors thank Tina Slee for research assistance and Dawn Case for manuscript preparation.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Kravitz has received unrestricted research grants from Pfizer during the past three years. Dr. Epstein gave two lectures on patient-physician relationships for Merck in 2009 in which no commercial products were discussed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix — Focus Group Guiding Questions

Appendix — Focus Group Guiding Questions

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Epstein, R.M., Duberstein, P.R., Feldman, M.D. et al. “I Didn’t Know What Was Wrong:” How People With Undiagnosed Depression Recognize, Name and Explain Their Distress. J GEN INTERN MED 25, 954–961 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1367-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1367-0