ABSTRACT

Background

Research has documented greater health care costs attributable to intimate partner violence (IPV) among women during and after exposure. However, no studies have determined whether health care costs for abused women return to baseline levels at some point after their abuse ceases.

Objective

We examine whether health care costs among women exposed to IPV converge with those of non-abused women during a 10-year period following the end of exposure.

Design

Retrospective cohort analysis.

Setting

Group Health Cooperative, a large integrated health care system in the Pacific Northwest.

Participants

Random sample of English-speaking women aged 18–64 enrolled within Group Health and who participated in a telephone survey between June 2003 and August 2005.

Measurements

Total health care costs over an 11-year period from January 1, 1992 to December 31, 2002 were compiled using automated health plan data and comparisons made among women exposed to IPV since age 18 and those who never experienced IPV. IPV included physical, sexual, or psychological violence involving an intimate partner, and was assessed using five questions from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System.

Results

Relative to women with no IPV history, total health care costs were significantly higher during IPV exposure, costs that were sustained for 3 years following the end of exposure. By the 4th year following the end of exposure to IPV, health care costs among IPV-exposed women were similar to non-abused women, and this pattern held for the remainder of the 10-year study period.

Conclusions

Policy makers should consider the ongoing needs of victims following abuse exposure. Interventions to reduce the prevalence of IPV or to mitigate the impact of IPV have the potential to reduce the rate of growth of health care costs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

A growing literature has documented increased health care costs ranging from 1.4 to 4 times higher for women who have been exposed to intimate partner violence (IPV) compared to other women.1–6 Increased health care use has been found for abused women across both inpatient and outpatient service settings.1,2.

Prior research has also documented that the greater health care utilization attributable to IPV is sustained for some period after direct exposure ends. For example, Rivara et al. report that health care use among women exposed to IPV was 20 percent higher during the 5-year period following the end of IPV compared with women who reported no experience with IPV during their lifetime.2 However, no studies, to date, have determined how and whether health care costs for abused women return to baseline levels at some point after IPV ceases. Specifically, do health care costs for women exposed to IPV converge with those of non-abused women after time elapses?

We bridge this information gap by examining health care costs among women while they were exposed to IPV and up to 10 years following the end of their exposure. Our goal is to estimate the impact of IPV on health care use and costs during the period of abuse exposure, as well as to examine the specific manner in which exposure impacts health care costs after abuse ends. The approach we take is to estimate the mean costs experienced by women exposed and not exposed to IPV for each of the 11 years we examine. This analytic strategy has not been applied to IPV, and we think it has several advantages over previously reported studies of the cost of IPV. First, our estimates allow for an explicit tracking of the economic consequences of IPV during and following women’s exposure on an annual basis. These data may be useful to public and private decision makers as they plan for and allocate population-based health care resources. Second, these data are necessary for conducting incremental cost effectiveness analyses of programs designed to reduce the impact of IPV.

METHODS

Design Overview

We compared total health care costs among women exposed to IPV during the period of abuse and for up to 10 years after women reported their abuse had stopped to age-matched women who had never been exposed to IPV during their adult lifetime. This study was conducted at Group Health Cooperative, the nation’s oldest and largest consumer-governed integrated group practice. Group Health serves approximately 550,000 enrollees in Washington State and northern Idaho. More than two thirds of enrollees receive care through its integrated group practice that operates in the Puget Sound region of western Washington and in metropolitan Spokane in eastern Washington. The remainder of Group Health’s enrollees receives care from a statewide contracted network of providers and facilities. Socio-demographic characteristics of the Group Health population are similar to those in the surrounding area; however, the Group Health population is more highly educated, and whites are slightly overrepresented and Asians slightly underrepresented compared to the surrounding area.7 Fewer Group Health enrollees live in rural settings compared to the state as a whole.7 Approximately 9% of Group Health enrollees under age 65 have insurance through Medicaid or the Washington Basic Health Plan, a ‘gap’ plan for Medicaid-ineligible persons without employer sponsored health insurance. Enrollment in Group Health is relatively stable over time, with only 15% of enrollees leaving each year. All study materials and protocols were approved by Group Health’s Institutional Review Board.

Setting and Participants

We provide a brief overview of the sampling and recruitment process, with details available elsewhere.7,8. A total of 6,666 English-speaking women aged 18–64 enrolled within Group Health were randomly sampled from the health plan membership files between June 2003 and August 2005. Women were mailed information explaining the study and informing them that they would be contacted by telephone to participate in a telephone survey. The study was presented as one that broadly assessed women’s health to protect women who may have been residing with their abuser. Women were then contacted by telephone and consented to participate, and the interview was done by telephone. Women were provided a $25 gift card for participating in the telephone survey.

Of the 6,666 women, 345 (5.2%) were ineligible when contacted–209 because they did not meet sampling criteria identified in the Group Health automated records, 3 had died, 15 were too ill, and 115 either did not speak English or had a hearing impairment that precluded their ability to complete a telephone interview. Among the 6,321 eligible women, the response rate was 56.4%, with 28.9% refusing to participate and 14.7% who could not be reached, resulting in 3,568 women completing telephone surveys. Of the 3,568 women who completed the telephone surveys, we excluded 297 women (8.3%) because they were not enrolled within Group Health for a full year during the period January 1, 1992 to December 31, 2002, or they did not provide start and stop dates of their abuse exposure. With these exclusions, the final analytic sample comprised 3,271 women (1,867 women who reported no IPV exposure since age 18 and 1,404 with IPV exposure since age 18).

Because of the response rate, we used logistic regression to predict the probability of participating in the survey as a function of age, length of enrollment at Group Health, and healthcare utilization in the year prior to the survey. Non-respondents were older (45.3 vs. 43.1 years) and were more likely to be nonusers of health care services (14.5% vs. 7.1%) when compared to respondents.2 However, despite these differences, the estimated probability of study participation was similar for women exposed to IPV compared to women who reported no IPV (0.58 vs. 0.57).2. These analyses indicate that non-response should not bias the estimated effects of exposure to IPV on cost and utilization.

Survey and Definitions

The telephone survey asked whether women had had an intimate partner since age 18, the gender of their current or most recent partner, the status of the partnership, and, if applicable, the beginning and ending years of the relationship. This information was gathered for women’s three most recent partners. These data provided the complete intimate partnership history for the past 5 years for 98.7% of all respondents. Finally, women were asked to estimate how many intimate partners they had had in their adult lifetimes, if they had had more than three.

Intimate partner violence exposure since age 18 was assessed using five questions covering physical, sexual or non-physical (e.g., threats, controlling behavior) IPV from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) 7,9–12. Women were classified as experiencing any IPV if they reported physical, sexual, or non-physical abuse on the BRFSS questions. Women who indicated the presence of abuse on the BRFSS were also asked about the year in which each abuse type started and stopped. Intimate partner violence was defined as physical, sexual, or psychologic violence between adults aged 18–64 years who were present or past sexual/intimate partners, in heterosexual or homosexual relationships. Intimate partners were defined as current or former spouses, non-marital partners, or dating partners in relationships lasting longer than 1 week. In concert with current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention definitions, an intimate partnership could have been present without a sexual relationship.13 Questions from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) and the Women’s Experience with Battering (WEB) Scale.14–17 The five BRFSS questions assessed exposure to physical abuse, sexual abuse (forced intercourse or sexual touching), fear due to anger or threats of an intimate partner, and controlling behavior; these are scored dichotomously. This survey has been widely used in the United States. The ten-item WEB was used to assess battering resulting from a woman’s perceived loss of power and control due to interaction with her partner. Each item is scored on a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Scores greater than 20 (range, 10–60) are indicative of battering. Women were classified as experiencing IPV if 1 they reported physical or sexual abuse, or threats, or chronic controlling behavior on the BRFSS questions, or 2 their score on the WEB for any partner was 20 or higher. The survey asked whether the respondent had had an intimate partner since age 18, the gender of the partner, the current status of the partnership, and, if applicable, the beginning and ending years of each relationship. This information was gathered for up to three partners, after which respondents were asked to estimate how many intimate partners they had in their adult lifetime. These data provided complete intimate partnership history for the past 5 years for 98.7% of all study subjects. As reported previously, approximately 77% of women with a history of IPV experienced physical and/or sexual abuse. 7

Health Care Costs

Detailed information on health services use and costs has been available for care provided to Group Health enrollees within the integrated group practice and from the contract network since 1991. 18 The cost system captures utilization data from 15 different systems at Group Health on a monthly basis, calculating the precise cost for each unit of service delivered and assigning costs to patients based on the units of service they utilized. Key characteristics of the cost methodology are that actual costs from the general ledger are reported, overhead costs are fully allocated to patient care departments, total costs are reduced to the unit of service, and there is systematic verification of the automated data. The automated data sources included costs for visits to primary and specialty care providers, emergency and urgent care visits, acute care hospitalizations, mental health and chemical dependency services, home care services, laboratory and radiologic services, and pharmaceutical utilization. The costs incurred by Group Health for any service received from contract providers or facilities outside of the integrated group practice are also included in the allocation model. These data are a key component of Group Health’s clinical improvement efforts, and have been validated in a variety of research and clinical applications. Nominal cost information collected from Group Health was adjusted to 2004 dollars using the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index for the Seattle-Tacoma-Everett Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA). 19

Cases and Controls

We assessed women’s health care cost data starting January 1, 1992, or her first date of enrollment in the health plan as an adult (aged ≥18 years). Follow-up for the assessment was through December 31, 2002, or the date of last dis-enrollment in the plan. A woman could have more than one start and stop date if she dis-enrolled and then re-enrolled in the health plan between 1992 and 2002. 2 To ensure complete capture of health services data for estimation of annual health care costs, the analyses only included follow-up years in which the woman was enrolled in Group Health for at least 2 months in each calendar quarter, for all four quarters of the year. 15

The primary aim of the analysis was to estimate costs associated with health services for abused women (cases) during abuse and as a function of time after the end of abuse, and to compare this cost trajectory to that of women who had not been exposed to IPV (controls). All time between when the abuse first started and the when the abuse ended were treated as “during” abuse for the purpose of our analysis. Since abuse may have spanned across multiple years, women may contribute multiple follow-up years to the estimates of cost and utilization measured “during” abuse.

All women who reported never having been exposed to IPV served as controls. Because there was no specific time period to anchor the time series of health care use among women not exposed to IPV, these control women were assigned to pseudo IPV exposure periods using an age-based frequency match to exposed women. We then considered the corresponding period of exposure for controls as their frequency-matched cases.

Statistical Analysis

We use repeated measures general estimating equations to examine the manner in which health care costs changed over time. Generalized estimating equation methods correct for the problem of correlated data structure that is common in health cost analyses and allow for missing data in a time series design,20,21 so an individual need not be enrolled within Group Health during each year of potential exposure or post exposure to IPV. We conducted our analyses from the health plan perspective using the subject-year as the unit of analysis. We estimated the regression using a gamma error distribution with a log link 22 and used the ‘sandwich’ method described by Huber to produce robust standard errors.22 Health care costs were adjusted for women’s age, race, education, income level and marital status, employment status and whether living in an urban or rural setting. Age was measured as of the calendar year for which costs were captured, but all other control variables were determined from the telephone survey. We adjust for underlying drivers of health care cost through the Resource Utilization Band (RUB) measure of the Adjusted Clinical Group (ACG) co-morbidity classification. 23–25 RUBs are a categorical variable ranging from 0–5 to reflect relatively low to high expected resource use, based on the diagnoses an individual received in the prior 12 months.

RESULTS

Of the 3,271 eligible women, 1,404 (42.9%) reported IPV exposure since age 18. The analysis focused on health care costs during abuse and up to 10 years after IPV ended. Follow-up years that occurred before the start of abuse or more than 10 years after abuse stopped were excluded from the analysis. A total of 1,245 women (545 cases, 700 controls) were excluded because they did not have at least one year of health care cost data during or within 10 years of the exposure period. The analytic sample included 1,167 women not exposed to IPV and 859 exposed women, and are described in Table 1. Because women were asked to report the year that they were first and last exposed to IPV, the exposure period for IPV includes multiple years of experience for most women. Therefore, women exposed to IPV contributed a total of 2,211 years of exposure to IPV for a mean of 5.1 (SD 3.7, maximum = 11) years per woman. Slightly less than one quarter (24%) of women surveyed said that their abuse was extremely severe, and 38.7% reported their abuse as not severe or slightly severe. Severity was based on each woman’s perception about how violent each abuse experience was, and women rated the overall severity of each IPV type over multiple partners using the following 4-point response scale: not violent, slightly violent, moderately violent, and extremely violent.

Compared to controls, women exposed to IPV were slightly older at the time of the baseline survey, more likely to be white and working at least part time, were less likely to have a college education, and were more likely to have lower incomes, although only the difference in income was statistically significant (Table 1).

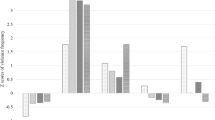

Adjusted total health care costs by year and IPV exposure are presented in Figure 1. Lifetime exposure to IPV resulted in $585 greater annual total health care costs during the period of abuse (p < 0.05), and these greater health care costs remained significantly (p < 0.05) higher for 3 years following the end of exposure. During this 3-year period following the end of exposure to IPV, the mean IPV-attributable costs ranged from $785 to $1,200. The difference in costs persisted into the 4th year, but the difference was not statistically significant. By the 5th year following the end of exposure, health care costs among women exposed and not exposed to IPV were similar, and this trend persisted for the entire 10-year follow-up period.

Similar results were also found for analyses of costs for inpatient services, visits to primary and specialty care providers and outpatient pharmacy use. Primary care costs were statistically greater (p < 0.05) in years 3 and 4 following the end of abuse, specialty care in year 2 following abuse and pharmacy cost in year 1 and 2 post-IPV exposure. Inpatient care costs were slightly more variable because relatively few individuals are hospitalized in any given year. Inpatient costs were statistically greater (p < 0.05) in years 3, 4, 5, and 9 following the end of exposure.

DISCUSSION

We examined health care costs up to 10 years following the end of exposure to intimate partner violence. Previous studies have reported on the health care costs of women exposed to IPV both during and following their exposure. Our study is unique in that we provide explicit estimates of the mean costs per year over an 11-year period, which provides health care decision makers with new information about the manner in which exposure to IPV effects health care seeking behavior.

Relative to women with no IPV history, total health care costs were significantly higher during IPV exposure, costs that were sustained for 3 years following the end of exposure. By the 4th year following the end of exposure to IPV, health care costs among women exposed to IPV were similar to women with no experience with IPV, and this pattern held for the remainder of the 10-year study period.

Health care costs may remain higher among abused women after their abuse exposure for several reasons. As prior studies have noted, women may continue to experience physical and emotional consequences of IPV years after their abuse exposure. 8,26,27 These emotional and physical complications could cause women to seek care for a period of years, a finding also supported by prior research. 2 Women may also feel the need to maintain a relationship with their abusive partner either for their own economic security or because of a desire to maintain a stable environment for their children, which could result in their continued use of health services through their partner’s insurance.

Our findings may underestimate the true impact of IPV on health care costs during periods of abuse because of our study design. We asked women to report the year that exposure to IPV began and ended, a crude estimation of abuse start and end dates; thus, the ‘exposed’ period may actually include a prolonged period for many women. On average, the women included in our analysis reported exposure for 14.5 (SD 11.1) years on average, and of these, 5.1 (SD 3.7) years of data on average are available from Group Health automated information systems. Because of this, the exposed period includes a wide range of experience and severity that limits the ability to characterize the impact of IPV exposure on health care use. An important implication of the parent study on which this analysis is based is that IPV should be considered as a chronic condition that has acute exacerbations, and our study definition was based on this understanding. Therefore, the multiple years during which a woman is exposed to IPV reflects IPV’s chronicity, but as with many other chronic medical conditions, health service use is likely to be heterogeneous over the course of the natural history of an illness.

The prolonged impact on health care costs associated with IPV is consistent with findings for a wide range of behaviors and health events such as tobacco use and alcohol and drug abuse. Our findings highlight the need for policy makers to consider the ongoing needs of women after abuse ends.28–32 In this regard, IPV may be more similar to a chronic health condition, in which the diagnostic and treatment phase must be followed by long-term management. 33 Our results may also point to a greater economic benefit from interventions designed to reduce the prevalence of IPV or to mitigate its impact once it has occurred. Interventions designed to positively impact women’s health have the potential to reduce the rate of growth of health care costs if these interventions are successful in effectively responding to women’s health care needs during and following their exposure to IPV.

References

Bonomi AE, Anderson ML, Rivara FP, Thompson RS. Health care utilization and costs associated with physical and non-physical intimate partner violence. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(3):1052–1067.

Rivara FP, Anderson ML, Fishman P, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs for women with a history of intimate partner violence. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(2):89–96.

Arias I, Corso P. Average cost per person victimized by an intimate partner of the opposite gender: A comparison of men and women. Violence Vict. 2005;20:379–391.

Snow Jones A, Dienemann J, Schollenberger J, et al. Long-term costs of intimate partner violence in a sample of female HMO enrollees. Womens Health Issues. 2006;16(5):252–261.

Coker AL, Reeder CE, Fadden MK, Smith PH. Physical partner violence and Medicaid utilization and expenditures. Public Health Rep. 2004;119:557–567.

Max W, Rice DP, Finkelstein E, Bardwell RA, Leadbetter S. The economic toll of intimate partner violence against women in the United States. Violence Vict. 2004;19(3):259–272.

Thompson RS, Bonomi AE, Anderson M, et al. Intimate partner violence: prevalence, types, and chronicity in adult women. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:447–457.

Bonomi AE, Thompson RS, Anderson ML, et al. Intimate partner violence and women’s physical, mental, and social functioning. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:458–466.

Vest JR, Catlin TK, Chen JJ, Brownson RC. Multistate analysis of factors associated with intimate partner violence. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22:156–164.

Verhoek-Oftedahl W, Pearlman DN, Coutu Babcock J. Improving surveillance of intimate partner violence by use of multiple data sources. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19(4):308–315.

Lemon SC, Verhoek-Oftedahl W, Donnelly EF. Preventive health care use, smoking and alcohol use among Rhode Island women experiencing intimate partner violence. J Women's Health Gend-Based Med. 2002;11(6):555–562.

Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Chronic disease and health risk behaviors associated with intimate partner violence—18 US states/territories, 2005. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(7):538–544.

Saltzman LE, Fanslow JL, McMahon PM. Intimate partner violence surveillance uniform definitions and recommended data elements, 1.0 ed. Atlanta GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1999.

Smith PH, Earp JA, DeVellis R. Measuring battering: development of the Women’s Experience of Battering (WEB) Scale. Women Health. 1995;1:273–288. 26.

Buehler J, Dixon B, Toomey K. Lifetime and annual incidence of intimate partner violence and resulting injuries—Georgia, 1995. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47:849–853.

Bensley L, Macdonald S, Van Eenwyk J. Wyncoop Simmons K, Ruggles D. Prevalence of intimate partner violence and injuries—Washington, 1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;59:589–592.

Hathaway J, Silverman J, Aynalem G, Mucci L, Brooks D. Use of medical care, police assistance, and restraining orders by women reporting intimate partner violence—Massachusetts, 1996–1997. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:485–488.

Fishman PA, Wagner EH. Managed care data and public health: the Experience of Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:477–491.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Databases, Tables and Calculators by Subject. Available at http://www.bls.gov/data. Accessed March 30, 2010.

Manning WG, Basu A, Mullahy J. Generalized modeling approaches to risk adjustment of skewed outcomes data. J Health Econ. 2005;24(3):465–488.

Manning WG, Mullahy J. Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform? J Health Econ. 2001;20(4):461–494.

Liang KY, Zeger SL. Regression analysis for correlated data. Annu Rev Public Health. 1993;14:43–68.

Weiner JP, Starfield BH, Steinwachs DM, Mumford LM. Development and application of a population-oriented measure of ambulatory care case-mix. Med Care. 1991;29(5):452–472.

Weiner JP, Starfield BH, Steinwachs DM, Mumford LM. Development and application of a population-oriented measure of ambulatory care case-mix. Med Care. 1991;29(5):452–472. 2.

The Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Group (ACG) Case-mix Adjustment System [computer program]. Version 6. Baltimore MD: The Johns Hopkins University; 2003.

Campbell J, Jones AS, Dienemann J, et al. Intimate partner violence and physical health consequences. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1157–1163.

Brokaw J, Fullerton-Gleason L, Olson L, Crandall C, McLaughlin S, Sklar D. Health status and intimate partner violence: a cross-sectional study. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:31–38.

Holder HD. Cost benefits of substance abuse treatment: an overview of results from alcohol and drug abuse. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 1998;1:23–29.

Jackson CA, Manning WG Jr, Wells KB. Impact of prior and current alcohol use on use of services by patients with depression and chronic medical illnesses. Health Serv Res. 1995;30:687–705. 48.

Holder HD, Cisler RA, Longabaugh R, Stout RL, Treno AJ, Zweben A. Alcoholism treatment and medical care costs from Project MATCH. Addiction. 2000;95:999–1013. 49.

Kane RL, Wall M, Potthoff S, McAlpine D. Isolating the effect of alcoholism treatment on medical care use. J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65:758–765. 50.

Parthasarathy S, Weisner CM. Five-year trajectories of health care utilization and cost in a drug and alcohol treatment sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80:231–240.

Nicolaidis C, Touhouliotis V. Addressing intimate partner violence in primary care: lessons from chronic illness management. Violence Vict. 2006;21(1):101–115.

Acknowledgements

Research supported by a grant from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, grant no. RO1 HS 10909

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fishman, P.A., Bonomi, A.E., Anderson, M.L. et al. Changes in Health Care Costs over Time Following the Cessation of Intimate Partner Violence. J GEN INTERN MED 25, 920–925 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1359-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1359-0