Abstract

Objective

To examine racial disparities in health care service quality.

Design

Secondary data analyses of visits by primary care service users in the Community Tracking Study household sample.

Setting

Sixty communities across the United States.

Participants

A total of 41,537 insured adult patients making sick visits to primary care physicians in 1996–1997, 1998–1999, 2000–2001, and 2003.

Measurements

Lag between appointment and physician visit, waiting time in physician office, and satisfaction with care were analyzed.

Results

Blacks but not other minorities were more likely to have an appointment lag of more than 1 week (13% white vs. 21% black, p < 0.001). Blacks, Hispanics, and other minorities were more likely to wait more than 30 min before being seen by the physician (16% white vs. 26% black, p < 0.001; vs. 27% Hispanic and 22% other minority, p < 0.001 and p = 0.02, respectively) and were less likely to report that they were very satisfied with their care (65% white vs. 60% black, p = 0.02; vs. 57% Hispanic and 48% other minority, p = 0.004 and p < 0.001, respectively). The differences in appointment lag and wait time remain large and statistically significant after the inclusion of multiple covariates, including geographic controls for CTS site. For all groups, satisfaction with care was affected by objective measures of service quality. Differences in objective measures of service quality explained much of the black-white difference in satisfaction, though not differences for other minority groups.

Conclusion

There are substantial racial/ethnic disparities in satisfaction with care, and these are related to objective quality measures that can be improved.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

BACKGROUND

In 2003 the US Institute of Medicine (IOM) released its landmark report Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Reviewing over a hundred studies, the report found that, on average, racial and ethnic minorities received heath care of a lower quality than that obtained by non-minorities and that these differences were disparities—they persisted after adjusting for differences in access-related factors, needs, and preferences.1 The report concentrated on technical quality, noting that minorities were less likely than whites to receive needed services, including clinically necessary procedures, and were more likely to receive less desirable services, such as amputation of all or part of a limb.

While much emphasis is placed on disparities in the technical quality of health, health care quality is a multifaceted concept that, in Donabedian’s classic formulation, also incorporates the interpersonal aspects of care and the amenities associated with the care experience.2 The IOM’s 2001 report Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century, which built on Donabedian’s formulation, identifies six aims for improving health care, including patient centeredness and timeliness.3 Optimization of the patient experience is also one of the three dimensions of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s (IHI) new “Triple Aim” initiative.4

These various non-technical service quality aspects of care matter greatly to patients. While patients have a strong preference for physicians of high technical quality, when asked to make tradeoffs, a substantial proportion still favor physicians of high interpersonal quality (promptness, courtesy/respect, timeliness).5 Moreover, these service aspects of quality may affect the ability to achieve technical quality and outcomes. Service quality can affect the quality of patient-provider communication and trust.2 Interpersonal quality is associated with improved adherence to physician recommendations.6 Appointment scheduling delays have been directly associated with higher mortality.7

Prior studies have found that Asians, blacks, and Hispanics were more likely than whites to be dissatisfied with the quality of their medical care and reported more subjective difficulty in getting an appointment and longer waiting times in a physician’s office.8–11 Barr et al. found no difference in general patient satisfaction between whites and minorities, but found that minorities were less satisfied than white patients with their direct interaction with their physicians.12 Mead and Roland found that minorities treated in English general practices waited longer for consultations than did non-minorities and that these differences in actual waiting times were an important explanation of differences in overall quality ratings between whites and minorities.13

Observed differences in technical quality can be explained, in part (though not entirely), by differences in access-related factors such as health insurance, income, educational attainment, and having a usual source of care.1 Some research suggests that technical quality differences may also reflect variation in the distribution of minority and majority populations across the country.14

The purpose of this study was to determine whether there are racial or ethnic disparities in the service quality of health care received by insured adult patients seen in physicians’ offices. The study examines disparities, controlling for many aspects of need for and access to care that may explain differences in quality outcomes. To that end, the study focuses on insured patients seen in physician offices to eliminate differences in service quality by race/ethnicity that are attributable to lack of access to care among uninsured populations and differences in service quality across types of care delivery. In robustness analysis, uninsured patients are also included in the sample.

This study builds on prior literature in three ways. First, this study uses both self-reported satisfaction, the most common measure of service quality, and objective measures of service quality: appointment lag (whether more than a week passed between the time an appointment was scheduled and the physician visit) and waiting time at the physician’s office (whether the patient waited more than 30 min before seeing the physician). Second, this study examines the effects of geographic location of care, which has been shown to be an important factor explaining observed differences in technical quality of care across race/ethnic groups. Finally, this study examines how objective service quality measures affect racial and ethnic differences in satisfaction.

METHODS

Study Design and Population

Data were drawn from the first four Community Tracking Study (CTS) Household Surveys (1996–1997, 1998–1999, 2000–2001, and 2003), conducted by the Center for Health System Change. These surveys include a representative sample of people in 60 sites across the US (51 metropolitan areas and 9 non-metropolitan areas). The survey was administered to a random sample of households in the 60 CTS sites and asked questions covering demographic information, health insurance type, utilization of health services, satisfaction with care, and health status.15 All four surveys were combined to generate sufficient sample size, particularly for analyses that include controls for CTS sites. All analyses used CTS-provided weighting variables.

Variables

All analyses were limited to insured, in-person, visits to primary care physicians (PCPs) for sickness or injury by insured adult patients (which constitute about 55% of visits by all insured adult respondents to the CTS). Analyses of appointment lags were further limited to those with lags less than or equal to 30 days to restrict to true sick visits. Long appointment lag was defined as waiting more than 7 days between making an appointment and seeing a doctor. This was approximately the 70th percentile of observed appointment lags (after truncation at 30 days). Long waiting time was defined as waiting more than 30 min before seeing the doctor. This was approximately the 85th percentile of observed waiting times and is consistent with the definition used by Mead and Roland.13 Satisfaction was defined as the percentage of those reporting that they were “very satisfied” with their health care, a score of 5 on a 5-point Likert scale.

Race and ethnicity was categorized as non-Hispanic white (the reference group), non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, and other minorities.

In multivariate analyses, covariates were included based on the factors that distinguish differences from disparities according to the IOM: demographic and health status covariates, which reflect need for care; socioeconomic and insurance covariates (including having a usual source of care), which reflect variation in access to care; and geographic location. Demographic variables included age (entered linearly and as a quadratic term) and gender. Health status was measured as “fair” or “poor” self-rated general health on a five-point scale and as having at least one hospital stay in the previous year. Socioeconomic covariates included education, employment status, marital status, and income (entered as its natural logarithm). Education was coded as less than high school, high school only, some college, and college or more. Full-time employment status was coded as working 35 h a week or more. Marital status was classified as married or not. Insurance type was coded as Medicare (with or without supplemental Medicaid or Medigap coverage), Medicaid only, private insurance only, and military insurance or other public coverage. CTS sites were coded as separate dummy variables.

Statistical Analysis

STATA version 8.0 was used for all statistical analyses. Data were analyzed across four survey waves. We compared the mean rate of long appointment lags, long waiting times, and satisfaction with care across the three race/ethnicity groups in univariate logistic analyses. We then conducted multivariate logistic analyses initially controlling for all but the geographic location covariates, and then adding geographic location dummy variables. Each dependent variable was analyzed separately, and these regressions were performed using all the observations available for each dependent variable.16

To assess whether differences in satisfaction across race and ethnic groups reflect differences in the objective of service quality experienced by these groups, the satisfaction analysis was repeated, including measures of appointment lags and waiting times. To assess whether minorities respond differently to the objective measures of service quality than do whites, we included interaction terms between race/ethnicity and long appointment lag/long waiting time in the multivariate analyses and tested for the size and significance of the interaction coefficients. We accounted for the complex survey design of the CTS using the complex survey modules available in STATA.17

In robustness analyses, we repeated analyses including the uninsured. We also repeated analyses including two more indicators of health status, the SF-12 Physical Component Summary score and the SF-12 Mental Component Summary score.18 We did not include these measures in the main analyses reported here because they were not part of the household survey in 2003 so that including these measures required omitting observations from 2003.

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic characteristics by race and ethnicity over all four survey periods of the Community Tracking Study. Blacks, Hispanics, and other minorities were younger than whites. They were more likely to report that they were in “fair” or “poor” health (26% black, 27% Hispanic, and 18% other minority vs. 13% white), while blacks, but not Hispanics or other minorities, were more likely to have had a hospital stay in the past year. Blacks, but not Hispanics or other minorities, were less likely to be privately insured (69% black, 72% Hispanic, and 76% other minority vs. 76% white). However, all minorities were more likely to be on Medicaid (8% black, 12% Hispanic, and 5% other minority vs. 2% white) and Hispanics and other minorities, but not blacks, were more likely to report no usual source of care (11% black, 16% Hispanic, and 18% other vs. 11% white). Blacks and Hispanics but not other minorities were less likely to have completed college. All minorities were less likely to be married and on average had lower incomes.

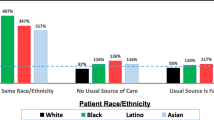

Blacks but not Hispanics or other minorities experienced longer appointment lags than did whites (Table 2). Whites waited more than 1 week for an appointment in 13% of cases, while blacks did so in 21% of cases (p = 0.02 relative to whites), and Hispanics and other minorities both did so in 16% of cases (p = 0.07 and p = 0.30 relative to whites, respectively). The odds ratio of waiting for more than 1 week for blacks relative to whites was 1.73 (p < 0.001); for Hispanics it was 1.27 (p = 0.06), and for other minorities it was 1.21 (p = 0.25). In multivariate analyses, controlling for non-site covariates, the odds remained unchanged for blacks [1.73 (p < 0.001)] and became significant for Hispanics [1.31 (p = 0.05)] but not other minorities (full multivariate results are available online [Appendix Table 1]). Adding site dummies decreased the significance of the odds for Hispanics [1.23 (p = 0.15)], whereas the odds increased for blacks [1.82 (p < 0.001)].

Blacks, Hispanics, and other minorities were more likely to have long wait times at the physician’s office than whites (Table 2). Whites waited longer than 30 min at the physician’s office in 16% of cases, whereas blacks did so in 26% of cases (p < 0.001 relative to whites), Hispanics did so in 27% of cases (p < 0.001 relative to whites), and other minorities did so in 22% of cases (p = 0.02 relative to whites). The odds ratio of waiting longer than 30 min at the doctor’s office for blacks relative to whites was 1.84 (p < 0.001); for Hispanics it was 1.93 (p < 0.001), and for other minorities it was 1.47 (p = 0.01). In multivariate analyses (full multivariate results are available online [Appendix Table 2]), these odds, although they do decrease, remained significant with the inclusion of both non-site and site covariates [1.48 (p < 0.001), 1.39 (p = 0.003), and 1.37 (p = 0.04), respectively).

Blacks, Hispanics, and other minorities were on average less likely to be very satisfied with their care than whites (Table 2). Sixty-five percent of whites rated being very satisfied with their care, whereas 60% of blacks rated being very satisfied (p = 0.02 relative to whites), 57% of Hispanics (p = 0.004 relative to whites), and 48% of other minorities gave such a rating (p < 0.001 relative to whites). The odds ratio of being very satisfied for blacks relative to whites was 0.83 (p = 0.02); for Hispanics it was 0.73 (p = 0.003), and for other minorities it was 0.50 (p < 0.001). After the inclusion of non-site covariates, these differences remained statistically significant for Hispanics and other minorities, but not blacks [0.87 (p = 0.10) for blacks, 0.81 (p = 0.04) for Hispanics, and 0.55 (p < 0.001) for other minorities] (full multivariate results are available online [Appendix Table 3]). The inclusion of site dummies had little effect on the odds ratios, but reduced the statistical significance of the results for Hispanics [0.87 (p = 0.10) for blacks, 0.85 (p = 0.12) for Hispanics, and 0.57 (p < 0.001) for other minorities].

Both waiting time and appointment lag had strong and significant effects on satisfaction (Table 3). The inclusion of these objective measures of service quality largely eliminated the difference between blacks and whites in satisfaction, but had less effect on the relationship between Hispanic ethnicity or other minority status and satisfaction. In analyses that included interaction terms between objective measures of service quality and race/ethnicity, the only significant interaction was that long appointment lags were less strongly associated with reduced satisfaction for Hispanics than for other groups (Table 3). Overall, the interaction results suggest that service quality is important to all racial and ethnic groups (full multivariate results are available online [Appendix Tables 4 and 5]).

The analyses conducted here included only insured patients. Rates of uninsurance are higher among minority groups, and the estimated effects here for insured populations may understate the service quality disadvantage of minorities overall by failing to include uninsured populations. We repeated the analyses including uninsured populations and including a dummy for uninsured. Including the uninsured population tended to increase the estimated effects of minority status on poor service outcomes.

The CTS includes only limited information about patient health status. We repeated the analyses including the SF-12 physical and mental health scores available in three of the surveys (1996–1997, 1998–1999, 2000–2001). Inclusion of these measures did not substantively affect the results.

Limitations

Measures of time spent waiting to see the doctor or to get an appointment were obtained by patient self-report and were not independently verified. To assess their validity, site level means of an alternative self-reported measure of time in the 2000 CTS household survey, travel time to the physician’s office, were compared with data on travel time to work obtained by the US Bureau of the Census in its 2000 Journey to Work Survey for the 28 sites that appeared in both datasets.19 The correlation between these related but distinct measures was 0.55, supporting use of these self-reported time measures as indicators of service quality.

Measures of appointment lag were only available for patients who saw a physician. To the extent that patients put off visits altogether or chose to use alternative sites of care, the long appointment lag variable will not fully capture the effect of delays. To assess this possibility, we examined responses to two additional CTS questions. First, respondents who had not had a visit were asked whether they put off a physician visit because of a long delay in getting an appointment. All three minority groups were more likely to report that they had put off a visit for this reason, with the effect reaching statistical significance for blacks [1.22 (p = 0.03)]. This finding suggests that appointment lags may be even longer for minorities than reported here. Second, we examined whether patients who had not had a visit had made their last visit to an emergency room instead. There was no difference across race/ethnicity groups in responses to this question. Results of these analyses are available online (Appendix Tables 6 and 7).

DISCUSSION

This study finds that blacks and other minorities experience worse service quality, as measured by appointment lags, waiting time, and satisfaction, than whites when using primary care in physicians’ offices. The results reported here with respect to appointment lag may even understate disparities, because minorities are more likely to report that they gave up and skipped a visit altogether because of long appointment lags. The findings persisted after controlling for health status, socioeconomic characteristics, insurance status, and presence of a usual source of care. In addition, in contrast to some other studies that find that disparities can be explained by differences in the geographic distribution of minorities across the country, our results were robust to the inclusion of site dummies.

The data available in the CTS cannot be used to examine differences in service quality at the level of the individual provider. The differences in service quality observed here could occur because minorities see different providers (within a given site) than do members of majority groups, and these providers have lower service quality for all their patients. Several studies have demonstrated that minority and majority populations see different providers and that minority patients often see providers who face more constraints on their practices.20,21

These results suggest that efforts to reduce disparities in the quality of care should go beyond technical quality and also consider the service quality of care. In our analysis, as in Mead and Roland’s recent paper, differences in objective measures of service quality explain almost all the difference in observed satisfaction between whites and blacks. Objective measures of service quality were important predictors of service quality for all groups, but for non-black minorities, other barriers, such as language or cultural obstacles, may contribute to the differences in satisfaction that persist after controlling for objective quality measures.

The relationship between disparities, objective measures of quality, and satisfaction is encouraging because strategies for improving these objective quality indicators exist. For example, Gordon and Chin describe the beneficial effects of a collaborative learning redesign on service quality in primary health clinics serving low income populations in New York City, and Schall et al. describe similar results in a series of Veterans’ Health clinics.22,23 Further research and demonstrations are needed to adapt these clinic-based models to office practices.

Improving service quality has the potential to improve outcomes. Studies have found lower adherence to medical management of chronic diseases in minorities.24,25 Aspects of the physician-patient relationship, especially trust, have been shown to have a significant effect in patient compliance, and blacks have been shown to have less trust in their physicians.26–30 Poor service quality may explain some of the differences in the willingness of groups to seek care and follow recommendations.

References

Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington: National Academy Press; 2003.

Donabedian A. The quality of care: how can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260:1743–48.

Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington: National Academy Press; 2001.

Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff. 2008;27:759–769.

Fung CH, Elliott MN, Hays RD, et al. Patients’ preferences for technical versus interpersonal quality when selecting a primary care physician. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:957–77.

Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, Ordway L, DiMatteo MR, Kravitz RL. Antecedents of adherence to medical recommendations: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. J Behav Med. 1992;15:447–68.

Prentice JC, Pizer SD. Delayed access to health care and mortality. Health Serv Res. 2007;42:644–62.

Shi L, Stevens GD. Disparities in access to care and satisfaction among US children: the roles of race/ethnicity and poverty status. Public Health Rep. 2005;120:431–41.

Shi L. Experience of primary care by racial and ethnic groups in the United States. Med Care. 1999;37:1068–77.

Taira DA, Safran DG, Seto TB, et al. Do patient assessments of primary care differ by patient ethnicity? Health Serv Res. 2001;36:1059–71.

Weech-Maldonado R, Morales LS, Elliott M, Spritzer K, Marshall G, Hays RD. Race/ethnicity, language, and patients’ assessments of care in Medicaid managed care. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:789–808.

Barr DA. Race/ethnicity and patient satisfaction: using the appropriate method to test for perceived differences in care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:937–43.

Mead N, Roland M. Understanding why some ethnic minority patients evaluate medical care more negatively than white patients: a cross sectional analysis of a routine patient survey in English general practices. BMJ. 2009;339:b3450.

Baicker K, Chandra A, Skinner JS. Geographic variation in health care and the problem of measuring racial disparities. Perspect Biol Med. 2005;48:S42–S53.

The response rates in chronological order were 65%, 63%, 61%, and 56.5%. More details are available at http://www.hschange.com/index.cgi?data=02. Accessed December 12, 2009.

Our study population numbered 41,537. The minimum number of observations in a regression was 30,953.

For site-specific estimates of the Household Survey, the variance estimates from STATA are identical to those generated by SUDAAN. More details are available at http://www.hschange.com/CONTENT/575/. Accessed December 12, 2009.

Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–33.

McGuckin N, Srinivasan N. Journey to work trends in the United States and its major metropolitan areas: 1960–2000. Publication No. FHWA -EP-03-058. Washington, DC: US Department of Transportation, 2003. Available at: http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ctpp/jtw/index.htm. Accessed December 12, 2009

Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL. Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:575–84.

Reschovsky JD, O’Malley AS. Do primary care physicians treating minority patients report problems delivering high-quality care? [Web Exclusive]. Health Aff. 2008;27:w222–w231. Available at: http://content.healthaffairs.org/cgi/reprint/27/3/w222. Accessed December 12, 2009.

Gordon P, Chin M. Achieving a new standard in primary care for low-income populations: case studies of redesign and change through a learning collaborative. The Commonwealth Fund, 2004. Available at: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/Content/Publications/Fund-Reports/2004/Aug/Achieving-a-New-Standard-in-Primary-Care-for-Low-Income-Populations--Case-Studies-of-Redesign-and-Ch.aspx. Accessed December 12, 2009.

Schall MW, Duffy T, Krishnamurthy A, et al. Improving patient access to the Veterans Health Administration’s primary care and specialty clinics. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2004;30:415–23.

Nguyen GC, LaVeist TA, Harris ML, Datta LW, Bayless TM, Brant SR. Patient trust-in-physician and race are predictors of adherence to medical management in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1233–9.

Morris AB, Li J, Kroenke K, Bruner-England TE, Young JM, Murray MD. Factors associated with drug adherence and blood pressure control in patients with hypertension. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26:483–92.

Thom DH, Ribisl KM, Steward AL, Luke DA. Further validation and reliability test of the Trust in Physician Scale. The Stanford Trust Study Physicians. Med Care. 1999;37:510–17.

Piette JD, Heisler M, Krein S, Kerr EA. The role of patient-physician trust in moderating medication nonadherence due to cost pressures. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1749–55.

Schneider J, Kaplan SH, Greenfield S, Li W, Wilson IB. Better physician-patient relationships are associated with higher reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1096–1103.

O’Malley AS, Sheppard VB, Schwartz M, Mandelblatt J. The role of trust in use of preventive services among low-income African-American women. Prev Med. 2004;38:777–85.

Boulware LE, Cooper LA, Ratner LE, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:358–65.

Acknowledgement

Research support was provided, in part, by the Commonwealth Fund.

Conflicts of Interest

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix Table 1

(DOC 49 kb)

Appendix Table 2

(DOC 49 kb)

Appendix Table 3

DOC 49 kb)

Appendix Table 4

DOC 53 kb)

Appendix Table 5

(DOC 61 kb)

Appendix Table 6

(DOC 49 kb)

Appendix Table 7

(DOC 49 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ly, D.P., Glied, S.A. Disparities in Service Quality Among Insured Adult Patients Seen in Physicians’ Offices. J GEN INTERN MED 25, 357–362 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1231-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1231-2