Abstract

BACKGROUND

Despite the availability of multiple effective screening tests for colorectal cancer, screening rates remain suboptimal. The literature documents patient preferences for different test types and recommends a shared decision-making approach for physician-patient colorectal cancer screening (CRCS) discussions, but it is unknown whether such communication about CRCS preferences and options actually occurs in busy primary-care settings.

OBJECTIVE

Describe physician-patient CRCS discussions during a wellness visit.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional; patients audio-recorded with physicians.

PARTICIPANTS

A subset of patients (N = 64) participating in a behavioral intervention trial designed to increase CRCS who completed a wellness visit during the trial with a participating physician (N = 8).

APPROACH

Transcripts were analyzed using qualitative methods.

RESULTS

Physicians in this sample consistently recommended CRCS, but focused on colonoscopy. Physicians did not offer a fecal occult blood test alone as a screening choice, which may have created missed opportunities for some patients to get screened. In this single visit, physicians’ communication processes generally precluded discussion of patients’ test preferences and did not facilitate shared decision-making. Patients’ questions indicated their interest in different CRCS test types and appeared to elicit more information from physicians. Some patients remained resistant to CRCS after discussing it with a physician.

CONCLUSION

If a preference for colonoscopy is widespread among primary-care physicians, the implications for intervention are either to prepare patients for this preference or to train physicians to offer options when recommending screening to patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the US.1 Despite effective prevention methods, CRC screening (CRCS) prevalence is suboptimal (≤50%).2,3 The difference between screening efficacy and use underscores the importance of physician recommendation and physician-patient communication about CRCS.

CRCS guidelines involve multiple tests that prevent or detect early CRC,4,5 but physicians’ knowledge of and adherence to guidelines varies.6,7 The American Cancer Society (ACS) acknowledges that there is no consensus on a “best” test or “gold standard,” endorses multiple CRCS options, and encourages health-care providers to recommend CRCS to average-risk adults 50 years old and older.8,9 Walsh and Terdiman 9 recommended that health-care providers offer choices to patients regarding CRCS, taking into account the existing guidelines, effectiveness of various options, and test availability. Previous studies have shown variation in patients’ preferences for CRCS options,10–13 indicating that the “best” test may be that which the patient is most likely to complete.

Better understanding of physician-patient CRCS discussions may help researchers develop more effective interventions to increase CRCS. Some educational and targeted CRCS materials have achieved modest increases (11–14%),14,15 but effects of more intensive tailored messages are not substantively different.16–19 Some physician-directed interventions increased CRCS,20,21 while others did not.22,23

The purpose of this study was to explore the content and process of physician-patient CRCS discussions during wellness visits and answer three general questions: “What (and how) do physicians tell patients about CRC and CRCS?”, “How do patients participate in these discussions and elicit information from physicians regarding CRC or CRCS?”, and “How do patients respond to CRCS information provided by physicians?” Our qualitative study fills a gap in the literature that includes few examples of direct observation of physician-patient discussions and a focus on quantifying aspects of communication.24–29

METHODS

We collected data as part of a supplement to a behavioral intervention trial, “Tailored Interactive Intervention to Increase CRCS” (5R01CA097263-02). Both studies were conducted at a large, multi-specialty clinic in Houston, Texas, and were approved by the institutional review board at the University of Texas-Houston, School of Public Health and the Research and Education Committee at Kelsey-Seybold Clinic (KSC).

Study Sample and Data Collection

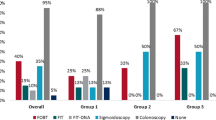

We recruited physicians through meeting announcements, letters, e-mail, and follow-up phone calls. All physicians in the Family Medicine and Internal Medicine departments at the KSC main campus location were eligible to participate. We then recruited patients enrolled in the intervention trial who completed the baseline survey and were scheduled for a wellness visit with a participating physician. Patients were eligible for the trial if they received primary care at KSC, but had not had a wellness visit in the last year, were 50–70 years old, spoke English, never had CRC or other colon diseases, and had never been screened or were due for CRCS. As part of the intervention trial, all patients met with research staff at the KSC Health Information Center 45 min before their appointment to provide written consent and review study materials, if applicable. Patients in the control group were not explicitly encouraged to stay or seek information, but were free to use the center’s resources. Patients in the two intervention arms of the trial were exposed to either a generic website or a tailored, interactive computer-delivered program that included information about four screening tests recommended by the ACS at the time of the study [fecal occult blood test (FOBT), sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, and barium enema].30 Both patients and physicians agreed to be audio-taped. Physicians’ nurses recorded patients’ visits.

Analysis Approach, Data Management, and Coding

Verbatim transcripts were reviewed and edited for accuracy. Prior to reading transcripts, investigators (AM, GM) prepared a preliminary codebook including code labels, definitions, and examples based on the original research questions and concepts from the literature (e.g., deductive etic codes).31 Three investigators (AM, GM, JB) independently coded transcripts and reviewed another coder’s transcripts using Atlas.ti software.32 Any coding differences or emergent, new codes resulted in modifications to the codebook or protocol.

Using a thematic analysis of the etic and emergent codes,33,34 one investigator (AM) led the analyses for themes and relations between the codes. Thematic analysis is a process for encoding qualitative data that supports our use of a mixed inductive and deductive approach to coding and analysis.33 Using our research questions to narrow the scope of analysis, themes emerged from the coded data and also were informed by the literature and the expertise of the research team.35,36 Results were presented to investigators and served as an opportunity to challenge perceptions, explore potential negative and deviant cases, and reduce potential bias.37 Initially, reports and tables of quotes by theme were stratified by intervention group and prior CRCS status to explore potential patterns in the data. Few differences were observed; therefore, data from all groups were combined.

RESULTS

Patient, Physician, and Visit Characteristics

Of the 9 Family Medicine and 11 Internal Medicine physicians invited to participate, 4 in each group agreed to be audio-taped. Data were collected between February 2006 and August 2007. Of 217 patients who were invited to participate, 177 agreed (82%). Of the 177 who agreed, 101 were not recorded for one of these reasons: patient failed to complete pre-visit meeting (n = 14) or wellness visit (n = 18), rescheduled with a non-participating physician (n = 1), decided not to be recorded (n = 2), or the recording failed due to staff or mechanical error (n = 66). Twelve patients with audio-recordings were excluded because they were already adherent to CRCS guidelines. Characteristics of the study sample are summarized in Table 1. No differences in patient characteristics were observed between trial participants who agreed or refused to be audio-taped or between audio-taped and all other trial participants.

Although four recordings were truncated and for five others it was unclear whether all physician-patient communication was recorded, all recordings included the common elements of the visit (history taking, physical exam, and physician orders such as laboratory work). Therefore, all 64 transcripts were coded and analyzed. Total visit length with the physician present ranged from 4.9 to 33.4 min (M = 16.0 min, SD = 7.1 min). CRCS was mentioned in 63 of 64 cases, and the 63 cases provide the data for the following results. Time spent discussing CRCS ranged from 3 s to 6 min (M = 1.7 min, SD = 1.7 min). CRCS was often mentioned more than once (73%), mainly due to physicians’ brief reminders at the end of the visit.

Research Question: What do physicians tell patients about CRC and CRCS?

Theme: Physicians consistently recommended colonoscopy for CRCS.

Physicians consistently recommended colonoscopy, described its benefits, and told patients how to schedule this test. Patients were told that CRCS was recommended at age 50 and that repeat colonoscopy was needed only every 10 years if the results were normal. Although no deadline for getting CRCS was stated, physicians occasionally mentioned “this year.” As in the following example, physicians described the thoroughness, efficacy, and efficiency of colonoscopy.

MD: Okay. So I like the colonoscopy because they see everything. If there’s any polyps, they take them out right then, and it’s a one-time deal. Whereas a flexible sigmoidoscopy—if they find anything, then they have to go back and do the whole thing. You have to come back a different day.

Most patients were referred to KSC’s onsite gastroenterology department, and the most common CRCS information physicians imparted involved the process of scheduling a colonoscopy.

MD: Have you ever had a colon test to look in your bottom with a light in the tube?

PT: No.

MD: Ok. So you need to call the GI department to schedule a consultation with them for colon cancer screening, and they will see you in the office initially, then after that they’ll schedule you for a colonoscopy.

However, physicians did not have a standard procedure for scheduling a gastroenterology appointment. Some told patients to call for an appointment (one physician consistently provided the phone number), some told patients that an appointment would be set up for them (or that someone would call them or that they would be put on a “call list”), and some told patients to set up an appointment when they checked out.

Theme: Physicians never offered FOBT alone for CRCS.

Annual home-based FOBT alone was never offered as a suitable option for CRCS. In the example below, the physician denigrated FOBT and stated its unacceptability for screening even when patients inquired.

PT: I’d like to do the stool test but I don’t really want to have that colonoscopy.

MD: Well you can’t just do the stool test. They need to look inside too.

Other physicians were more indirect in their dismissal of FOBT by focusing on colonoscopy as the optimal test, even when patients expressed barriers to colonoscopy. One physician frequently referred to colonoscopy as the “gold standard” for CRCS. Sigmoidoscopy with FOBT was sometimes recommended by physicians as an alternative to colonoscopy, but FOBT alone was not.

Research Question: How do physicians tell patients about CRC and CRCS?

Theme: Physicians differed in the persuasive techniques they employed

During the history-taking process, all physicians asked if the patient had ever been screened or whether they recently had a colonoscopy. Most CRCS discussions occurred after the history and during the physical exam. One physician frequently adopted a tone reflecting considerable dismay upon hearing that a patient had never had CRCS and was several years overdue. Another physician attempted to persuade patients to get a colonoscopy by stressing the negative impact of cancer compared to the screening procedure, frequently asking patients “Would you rather have colon cancer?” Typically, physicians simply directed patients to get a colonoscopy; however, some physicians occasionally asked for patients’ agreement with their recommendation for colonoscopy.

Theme: Physicians differed in their use of office-based FOBT and CRCS orders

Some physicians conducted office-based FOBTs. In all cases, patients were told no blood was found in their stool, but in no case did a physician explain why the other recommended test(s) was still needed. Some physicians recommended sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy, but then also prescribed a home-based FOBT without explaining why multiple tests were needed. Physicians also differed in how they ordered different tests. For example, for laboratory tests and mammography, patients received a copy of the written order. In contrast, for endoscopy, the patient was instructed to “call and make an appointment” or “get scheduled” with the gastroenterology department.

Research Question: How do patients participate in these discussions and elicit information from physicians regarding CRC or CRCS?

Theme: Patients’ questions for physicians increased their information receipt

Many patients had at least one CRCS question for the physician. Most questions concerned differences between the test types, time, cost/insurance coverage, pain, preparation, and general understanding of the process. Some patients asked which test physicians recommended or thought was best. Patients’ questions created more interactive communication and increased their receipt of CRCS-related information.

MD: …they’ll see you for a consult first and then schedule you for a colonoscopy after that.

PT: Which is the lower colon or the complete one?

MD: The entire colon.

PT: You think I should have the entire one as opposed to the lower?

MD: Yep.

PT: And that’s because?

MD: Everybody should.

PT: [Laughter]

Despite physicians’ focus on colonoscopy, patients often asked or reported preferences for other tests. Also, as illustrated in the following quote, patients seemed to perceive a hierarchy starting with FOBT (the “first” or easiest test), then sigmoidoscopy, then colonoscopy (the “last,” most intensive test).

PT: I want the middle one—the one that—I don’t know, to me it seems like that first one—I don’t remember what’s that called?

MD: Where it goes all the way?

PT: The one that you test yourself.

MD: Oh, no. That one’s no good.

PT: Okay. And then the last one is the one that they put you to sleep or something like that.

MD: That’s the good one.

Theme: Patients’ expressed barriers to CRCS

About one-third of patients overtly expressed specific barriers to or uncertainties about CRCS. Patients expressed concerns about pain, side effects, and test invasiveness. Patients also mentioned cost, distance to the clinic, needing a ride home, and scheduling/making time for the exam. Some patients with prior CRCS experience expressed dislike of the preparation or the uncomfortable test procedure.

Research Question: What do physicians tell patients about CRC and CRCS?

Theme: Physicians’ responses to patients’ expressed barriers to CRCS

Physicians generally provided brief, non-specific encouragement when patients expressed barriers to CRCS.

PT: So you recommend that…it’s okay to go through that thing I did?

MD: The colonoscopy?

PT: Yes

MD: 100%—that’s the best way to screen for colon cancer, which is one of the biggest killers in cancer so it’s very, very important

PT: I talked to the doctor and he scared me

MD: What?

PT: He said if I puncture you…

MD: Please go; it’s very, very important.

PT: Well it still scared me and I didn’t come back, plus I forgot.

MD: Ok, well don’t forget please

In some cases, physicians offered specific solutions to reported barriers, but FOBT was never offered as a solution to endoscopy barriers. The example below illustrates how a physician addressed a practical, financial barrier that caused the patient to cancel a previously scheduled colonoscopy and missed an opportunity to discuss all test options.

MD: Colon test to look in your bottom with a light and a tube? You were scheduled.

PT: Yeah.

MD: So what happened?

PT: You know they asked me to bring $500.00, and I didn’t have it so I told them I can’t pay.

MD: Can you afford it now?

PT: I don’t think I can afford it right now.

MD: Okay, so…

PT: Is there another—isn’t there another—something else one can do except, you know, going through that colonoscopy?

MD: That’s the most efficient one, because even if you did a barium enema, we still need a flex-sig to go in your bottom.

PT: So they still need my $500.00?

MD: Did you change insurance?

PT: It is the same insurance….

MD: Well, you want to go see [a gastroenterologist] and discuss that, and see, if [the gastroenterologist] recommends other options? And they can run your insurance and see what the cost is, in case they have changed your co-pay.

Another example illustrates a physician’s proposed solution to a practical scheduling barrier.

MD: Maybe you could set everything up on the same day—the mammogram and the colonoscopy. So then you’ll only have to take 1 day off.

PT: Okay. I can do it on Monday because I don’t work Sunday

MD: That would be best. Yeah, so that it won’t interfere with you taking care of your child.

PT: Uh-huh (affirmative).

Research Question: How do patients respond to CRCS information provided by physicians?

Theme: Patients’ resistance to CRCS

Although several patients indicated that they did not want to have endoscopy, others voiced justifications that “excused” them from needing CRCS, such as “everything is fine,” “I don’t have any family history [of CRC],” “I’m of the opinion that if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” or “never had any reason to” as illustrated below.

MD: Okay. All right, but you never had a colonoscopy or sigmoidoscopy?

PT: No.

MD: Okay.

PT: Really never had any reason to.

MD: Well you have. [Laughing].

PT: Okay. [Laughing]. Well…

MD: Because we all do have a reason…

PT: Yes we do. I understand, but I’ve just been healthy.

Despite acknowledgement of prior CRCS discussions and recommendations, one patient told her physician that no one had said that she had to get CRCS. When two physicians stated that patients could refuse CRCS, both patients refused. Several patients also exhibited defenses for other preventive health concerns, as illustrated in the example below.

PT: I never get a mammogram.

MD: Okay.

PT: Everybody wants me to have one. I don’t need a mammogram.

The final quotes illustrate how a patient remains uncommitted to getting CRCS despite the physician’s attempts to correct the patient’s misperceptions or biases about CRCS.

PT: No I don’t want that. Men I think are more likely, I understand, they have colon cancer more than women.

MD: No, no. That’s not true.

PT: That’s not?

MD: We see it in both sexes, and it’s recommended for screening both sexes.

PT: Really?

MD: Absolutely.

PT: Well don’t you have certain symptoms that you look for?

MD: Often times no, and especially for early precancerous polyps, none.

PT: Well, really? Huh. Well you’d have to knock me out to do that.

MD: Well I can send you to the GI specialist and they can do a colonoscopy. They do sedate you for that. Okay?

PT: I don’t know.

DISCUSSION

We identified three major themes from the data that may contribute to low CRCS rates and that may be targets for future intervention: physicians’ focus on colonoscopy, barriers to CRCS, and patients’ confusion about or rejection of CRCS.

First, primary-care physicians in this sample regularly recommended CRCS, but focused on colonoscopy, which is consistent with a national survey of physicians 7 and the recent increase in colonoscopy and decrease in FOBT use.2 Physicians’ communication processes generally precluded discussion of patient preferences and choice of test type. Rejecting FOBT alone as a sufficient screening method may have created missed opportunities for some patients to get screened. Additionally, some physicians conducted office-based FOBTs despite evidence suggesting that these tests should not be used 38,39, which may have confused patients about the need for additional CRCS tests.

Our findings prompt the question “Why did physicians focus on colonoscopy to the exclusion of other tests?” Some physicians may be confused by the guidelines,6 which have been modified over time, include different tests,4,5,40,41 and provide little or no guidance on strategies to increase patient compliance.42 Physicians may perceive colonoscopy to be the standard of care.7,43 Some physicians may reduce the menu of test options to save time or reduce patients’ “information-overload.” 44,45 Competing demands for time may be a barrier to discussing CRCS options,43 and focusing on one test may seem like a better use of time, particularly when gastroenterology services are readily available, as was the case at this clinic.46 Physicians also may believe that they will persuade patients to get a colonoscopy over successive visits; however, continuity of care has been associated with more FOBT and less endoscopy use 47 and lower CRCS among patients overdue for health screenings.48

Second, some patients may not have made any progress toward CRCS due to unresolved questions about or barriers to CRCS. Although patients’ questions appeared to increase the content and interactive nature of CRCS discussions, there was little discussion of test options. Patients’ barriers decrease CRCS adherence,49 and physicians’ general encouragement to overcome or ignore barriers may not be sufficient. Physicians are still the most trusted source for health information,50 and those willing to engage in shared decision making may increase patients’ CRCS adherence.

Third, not all patients were motivated to get CRCS. Some patients distinguished between physician recommendations and “requirements,” and when given an opportunity to refuse CRCS, they did. Self-exemption beliefs 51,52 such as ‘never had any reason to [get a colonoscopy]…I’ve been healthy’ were the most common defensive processes expressed by patients. These beliefs and misconceptions protect individuals from accepting personal risk susceptibility and obviate their perceived need for screening.

Implications for Intervention

If physicians’ focus on colonoscopy is widespread, interventions should prepare patients for physicians’ preferences, teach negotiation skills if patients prefer different tests, or train physicians to present all test options.9,53 Which strategy to use should be informed by future studies that determine whether patient adherence increases when test acceptability, preferences, and barriers are addressed using a shared-decision making approach.12,54 To reduce patient barriers and ambivalence, physicians should recommend FOBT as an acceptable CRCS option,55,56 and clinics should assist with scheduling endoscopy appointments.57,58

Limitations

This study involved one clinic site and a small number of Family Medicine and Internal Medicine physicians. Patients were participants in a concurrent trial designed to increase CRCS, agreed to schedule a wellness visit, and had medical insurance. Our use of audio-recordings precluded our ability to examine non-verbal communication,59 but was unlikely to significantly affect physician or patient behavior.60 However, similar to other studies of this type, our participants may be biased toward those who feel more confident in their relationships and communications with others.60 Our study may underestimate the amount and type of CRCS information given to patients over successive visits. Some patients had existing medical conditions, and physicians would rightly focus more time on those. Similar to other qualitative research, the purpose of this study was not to generalize results to a target population of patients and physicians, but rather to describe the phenomena of interest in detail using the original language of the participants.61 Our heuristic findings, along with other published studies, inform future CRCS research and interventions. Our findings also may be useful to clinicians who evaluate their communication practices with patients and consider modifying their approach when discussing CRCS.

References

Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States 2009: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:27–41.

Meissner HI, Breen NL, Klabunde CN, Vernon SW. Patterns of colorectal cancer screening uptake among men and women in the US. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(2):389–94.

Shapiro JA, Seeff LC, Thompson TD, Nadel MR, Klabunde CN, Vernon SW. Colorectal cancer test use from 2005 National Health Interview Study. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2008;17(7):1623–30.

Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Smith RA, Brooks D, Andrews KS, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008 March 5, 2008.

U. S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Task Force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):627–37.

Klabunde CN, Frame PS, Meadow A, Jones E, Nadel MR, Vernon SW. A national survey of primary care physicians’ colorectal cancer screening recommendations and practices. Prev Med. 2003;36:352–62.

Klabunde CN, Lanier D, Nadel MR, McLeod C, Yuan G, Vernon SW. U.S. primary care physicians’ colorectal cancer screening recommendations and practices, 2006–2007. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(1):8–16.

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures, 2008. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2008.

Walsh JME, Terdiman JP. Colorectal cancer screening. Clinical applications. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289(10):1297–302.

Leard LE, Savides TJ, Ganiats TG. Patient preferences for colorectal cancer screening. J Fam Pract. 1997;45(3):211–8.

Ling BS, Moskowitz MA, Wachs D, Pearson B, Schroy PC. Attitudes toward colorectal cancer screening tests. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:822–30.

Hawley ST, Volk RJ, Krishnamurthy P, Jibaja-Weiss ML, Vernon SW, Kneuper S. Preferences for colorectal cancer screening among racially/ethnically diverse primary care patients. Med Care. 2008;46(9 (Suppl 1)):S5–9.

Pignone MP, Bucholtz D, Harris R. Patient interest and preferences for colon cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(suppl 1):96.

Denberg TD, Coombes JM, Byers TE, Marcus AC, Feinberg LE, Steiner JF, et al. Effect of a mailed brochure on appointment-keeping for screening colonoscopy. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(12):895–900.

Pignone MP, Harris RP, Kinsinger LS. Videotape-based decision aid for colon cancer screening: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(10):761–9.

Costanza ME, Luckmann R, Stoddard AM, White MJ, Stark JR, Avrunin JS, et al. Using tailored telephone counseling to accelerate the adoption of colorectal cancer screening. Cancer Detection & Prevention. 2007;31:191–8.

Marcus AC, Mason M, Wolfe P, Rimer BK, Lipkus I, Strecher V, et al. The efficacy of tailored print materials in promoting colorectal cancer screening: results from a randomized trial involving callers to the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Information Service. J Health Commun. 2005;10(Suppl 1):83–104.

Myers RE, Sifri R, Hyslop T, Ronsenthal M, Vernon SW, Cocroft J, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the impact of targeted and tailored interventions on colorectal cancer screening. Cancer. 2007;110(9).

Rawl SM, Champion VL, Scott LL, Zhou H, Monahan PO, Ding Y, et al. A randomized trial of two print interventions to increase colon cancer screening among first-degree relatives. Patient Education & Counseling. 2008;71:215–27.

Ferreira MR, Dolan NC, Fitzgibbon ML, Davis TC, Gorby N, Ladewski L, et al. Health care provider-directed intervention to increase colorectal cancer screening among veterans: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(7):1548–54.

Lane D, Messina C, Cavanagh M, Chen J. A provider intervention to improve colorectal cancer screening in county health centers. Med Care. 2008;46(9 (Suppl 1):S109–16.

Ruffin MT, Gorenflo DW. Interventions fail to increase cancer screening rates in community-based primary care practices. Prev Med. 2004;39:435–40.

Walsh JME, Salazar R, Terdiman JP, Gildengorin G, Perez-Stable EJ. Promoting use of colorectal cancer screening tests: can we change physician behavior. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:1097–101.

Lafata JE, Divine G, Moon C, Williams K. Patient-physician colorectal cancer screening discussions and screening use. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(3):202–9.

Shokar NK, Carlson CA, Shokar GS. Physician and patient influences on the rate of colorectal cancer screening in a primary care clinic. J Cancer Educ. 2006;21:84–8.

Canada RE, Turner BJ. Talking to patients about screening colonoscopy - where conversations fall short. The Journal of Family Practice. 2007;56(8):E1–9.

Wackerbarth SB, Tarasenko YN, Joyce JM, Haist SA. Physician colorectal cancer screening recommendations: an examination based on informed decision making. Patient Education & Counseling. 2007;66:43–50.

Ling B, Trauth J, Fine M, Mor M, Resnick A, Braddock C, et al. Informed decision-making and colorectal cancer screening: is it occuring in primary care. Med Care. 2008;46(9 (suppl 1):S23–9.

Wolf MS, Baker DW, Makoul G. Physician-patient communication about colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(11):493–9.

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures, 2007. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2007.

MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Kay K, Milstein B. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cultural Anthropology Methods. 1998;10(2):31–6.

ATLAS.ti. Germany: Scientific Software Development; 2004.

Boyatzis RE. Transforming qualitative information: thematic analysis and code development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998.

Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2006;5(1):80–92.

Charmaz K. Grounded theory. In: Smith JA, Harre R, Van Langahove L, eds. Rethinking methods in psychology. London: Sage; 1995:27–49.

Henwood KL, Pidgeon NF. Qualitative research and psychological theorizing. Br J Psychol. 1992;83:97–111.

Esterberg KG. Qualitative research methods in social research. Boston: McGraw-Hill; 2002.

Collins JF, Lieberman DA, Durbin TE, Weiss DG. The Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group. Accuracy of screening for fecal occult blood on a single stool sample obtained by digital rectal examination: a comparison with recommended sampling practice. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(2):81–6.

Sox HC Jr. Office-based testing for fecal occult blood: do only in case of emergency. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(2):146–8.

Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ. Cancer Screening in the United States, 2007: a review of current guidelines, practices, and prospects. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(2):90–104.

U. S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: recommendations and rationale. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:129–31.

Berg AO. The aftermath of efficacy. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(1):3–4.

Guerra CE, Schwartz JS, Armstrong K, Brown JS, Halbert CH, Shea JA. Barriers of and facilitators to physician recommendation of colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(12):1681–8.

Griffith KM, Lewis CL, Brenner ART, Pignone MP. The effect of offering different numbers of colorectal cancer screening test options in a decision aid: a pilot randomized trial. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2008;8(4).

Lance P. Colorectal cancer screening: confusion reigns. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2008;17(9):2205–7.

Achkar E. Colorectal cancer screening in primary care: the long and short of it. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(5):837–8.

Fenton JJ, Franks P, Reid RJ, Elmore JG, Baldwin LM. Continuity of care and cancer screening among health plan enrollees. Med Care. 2008;46(1):58–62.

Zhu J, Davies J, Taira DA, Yamashita M. The impact of seeing physicians new to a patient on the response to screening reminders. Med Care. 2006;44(10):908–13.

McQueen A, Vernon SW, Myers RE, Watts BG, Lee ES, Tilley BC. Correlates and predictors of colorectal cancer screening among male automotive workers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers and Prevention. 2007;16(3):500–9.

Hesse BW, Nelson DE, Kreps GL, Croyle RT, Arora NK, Rimer BK, et al. Trust and sources of health information: the impact of the Internet and its implications for health care providers: findings from the first Health Information National Trends Survey. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(22):2618–24.

Chapman S, Wong WL, Smith W. Self-exempting beliefs about smoking and health: differences between smokers and ex-smokers. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(2):215–9.

Oakes W, Chapman S, Borland R, Balmford J, Trotter L. “Bulletproof skeptics in life’s jungle”: which self-exempting beliefs about smoking most predict lack of progression towards quitting? Prev Med. 2004;39:776–82.

Briss PA, Rimer B, Reilley B, Coates RC, Lee NC, Dolan-Mullen PD, et al. Promoting informed decisions about cancer screening in communities and healthcare systems. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(1):67–80.

Wolf RL, Basch CE, Brouse CH, Shmukler C, Shea S. Patient preferences and adherence to colorectal cancer screening in an urban population. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(5):809–11.

Winawer S, Fletcher RH, Rex DK, Bond J, Burt RW, Ferrucci JT, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(2):544–60.

Zauber AG, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Knudsen AB, Wilschut J, Van Ballegooijen M, Kuntz KM. Evaluating test strategies for colorectal cancer screening: a decision analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):659–69.

Holt CL, Schroy PCr. A new paradigm for increasing use of open-access screening colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(4):377–8.

Denberg TD, Myers BA, Lin C, Levine J. Screening colonoscopy through telephone outreach without antecedent provider visits: a pilot study. Prev Med. 2009;48:91–3.

Haskard KB, DiMatteo MR, Heritage J. Affective and instrumental communication in primary care interactions: predicting the satisfaction of nursing staff and patients. Health Communication. 2009;24(1):21–32.

Themessl-Huber M, Humphris G, Dowell J, Macgillivray S, Rushmer R, Williams B. Audio-visual recording of patient-GP consultations for research purposes: a literature review on recruiting rates and strategies. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;71:157–68.

Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a National Cancer Institute R01 grant (no. 097263; PI: Sally W. Vernon) and an American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant (CPPB-113766; PI: Amy McQueen). We gratefully acknowledge the support of the physicians and patients in the Family Medicine and Internal Medicine Departments at Kelsey-Seybold Clinic. We also thank Nicholas Solomos, MD, for his insightful comments on the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McQueen, A., Bartholomew, L.K., Greisinger, A.J. et al. Behind Closed Doors: Physician-Patient Discussions About Colorectal Cancer Screening. J GEN INTERN MED 24, 1228–1235 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1108-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1108-4