Abstract

The American College of Physicians (ACP), Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM), American Geriatric Society (AGS), American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) developed consensus standards to address the quality gaps in the transitions between inpatient and outpatient settings. The following summarized principles were established: 1.) Accountability; 2) Communication; 3.) Timely interchange of information; 4.) Involvement of the patient and family member; 5.) Respect the hub of coordination of care; 6.) All patients and their family/caregivers should have a medical home or coordinating clinician; 7.) At every point of transitions the patient and/or their family/caregivers need to know who is responsible for their care at that point; 9.) National standards; and 10.) Standardized metrics related to these standards in order to lead to quality improvement and accountability. Based on these principles, standards describing necessary components for implementation were developed: coordinating clinicians, care plans/transition record, communication infrastructure, standard communication formats, transition responsibility, timeliness, community standards, and measurement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

BACKGROUND

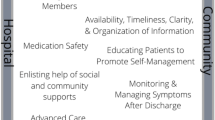

Studies of the transition of care between inpatient and outpatient settings have shown that there are significant patient safety and quality deficiencies in our current system. The transition from the hospital to the outpatient setting has been more extensively studied than the transition from the outpatient to the inpatient setting. One prospective cohort study found that one in five patients discharged from the hospital to home experience an adverse event, defined as an injury resulting from medical management rather than from the underlying disease, within three weeks of discharge1. This study also concluded that 66% of these were drug-related adverse events, many of which could have been avoided or mitigated. Another prospective cross-sectional study found that approximately 40% of patients have pending test results at the time of discharge and that 10% of these require some action; yet outpatient physicians and patients are unaware of these results2. Medication discrepancies have also been shown to be prevalent with one prospective observational study showing that 14% of elderly patients had one or more medication discrepancies and of those patients with medication discrepancies 14% were re-hospitalized at 30 days compared to 6% of the patients who did not experience a medication discrepancy3. A recent review of the literature cited improving transitional care as a key area of opportunity to improve post-discharge care4.

Lack of communication has clearly been shown to adversely affect post-discharge care transitions5. A recent summary of the literature by an Society of Hospital Medicine/Society of General Internal Medicine Task Force found that direct communication between hospital physicians and primary care physicians occurs infrequently (in 3%-20% of cases studied), the availability of a discharge summary at the first post-discharge visit is low (12%-34%) and did not improve greatly even after 4 weeks (51%-77%), affecting the quality of care in approximately 25% of follow-up visits5. This systematic review of the literature also found that discharge summaries often lack important information such as diagnostic test results, treatment or hospital course, discharge medications, test results pending at discharge, patient or family counseling, and follow-up plans.

However, the lack of studies of the communication between ambulatory physicians and hospital physicians prior to admission or during emergency department (ED) visits does not imply that this communication is not equally important and essential to high quality care. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), the greatest source of hospital admissions in many institutions is through the emergency department. Over 115,000,000 visits were made to the nation’s approximately 4,828 emergency departments in 2005, and about 85.2 percent of ED visits end in discharge6. The emergency department is also the point of re-entry into the system for individuals who may have had an adverse outcome linked to a prior hospitalization6. Communication between hospital physicians and primary care physicians must be established to create a loop of continuous care and diminish morbidity and mortality at this critical transition point.

While transitions can be a risky period for patient safety, observational studies suggest there are benefits to transitions. A new physician may notice something overlooked by the current caregivers7–12. Another factor contributing to the challenges of care transitions is the lack of a single clinician or clinical entity taking responsibility for coordination across the continuum of the patient’s overall healthcare, regardless of setting13. Studies indicate that a relationship with a medical home is associated with better health, on both the individual and population levels, with lower overall costs of care and with reductions in disparities in health between socially disadvantaged subpopulations and more socially advantaged populations14. Several medical societies have addressed this issue, including the American College of Physicians (ACP), Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM), American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and have proposed the concept of the “medical home” or “patient centered medical home” which calls for clinicians to assume this responsibility for coordinating their patients’ care across settings and for the healthcare system to value and reimburse clinicians for this patient-centered and comprehensive method of practice15–17.

Finally, patients and their family or caregivers have an important role to play in transitions of care. Several observational and cross-sectional studies have shown that patients and their caregivers and family express significant feelings of anxiety during care transitions. This anxiety can be caused by a lack of understanding and preparation for their self-care role in the next care setting, confusion due to conflicting advice from different practitioners, a sense of abandonment attributable to the inability to contact an appropriate healthcare practitioner for guidance, and they report an overall disregard for their preferences and input into the design of the care plan18–20. Clearly there is room for improvement in all these areas of the inpatient and outpatient care transition and the Transitions of Care Consensus Conference (TOCCC) attempted to address these areas by developing standards for the transition of care that also harmonize with the work of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation’s Stepping up to the Plate (ABIMF SUTTP) Alliance (21 in press). In addition, other important stakeholders are addressing this topic and actively working to improve communication and continuity in care including Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and the National Quality Forum (NQF). In summary, it is clear that there are qualitative and quantitative deficiencies in transitions of care between the inpatient and outpatient setting that are affecting patient safety and experience with care.

METHODS

The executive committees of the ACP, SGIM, and SHM agreed to jointly develop a policy statement on transitions of care. Transitions of care specifically between the inpatient and outpatient settings was selected as an ideal topic for collaboration for the three societies as they represent the continuum of care for internal medicine within these settings. To accomplish this, a consensus conference was convened to develop consensus guidelines and standards around transitions between inpatient and outpatient settings through a multi-stakeholder process. The steering committee (see Appendix for roster) developed the agenda and invitee list for the consensus conference.

RECOMMENDATIONS ON PRINCIPLES AND STANDARDS FOR MANAGING TRANSITIONS IN CARE BETWEEN THE INPATIENT AND OUTPATIENT SETTINGS FROM THE ACP, SGIM, SHM, AGS, ACEP, AND SAEM

The TOCCC first proposed a framework that provides guiding principles for what we would like to measure and eventually report. From those principles are developed a set of preferred practices or standards; the standards are more granular and allow for more specificity in describing the desired practice or outcome and its elements. Standards then provide a roadmap for identification and development of performance measures.

The TOCCC established the following principles:

-

Accountability

-

Communication: clear and direct communication of treatment plans and follow-up expectations

-

Timely feedback and feed forward of information

-

Involvement of the patient and family member, unless inappropriate, in all steps

-

Respecting the hub of coordination of care

-

All patients and their family/caregivers should have and be able to identify who is their medical home or coordinating clinician (i.e., practice or practitioner).

-

At every point along the transition the patient and/or their family/caregivers need to know who is responsible for their care at that point and who to contact and how.

-

National standards should be established for transitions in care and should be adopted and implemented at the national and community level through public health institutions, national accreditation bodies, medical societies, medical institutions etc, in order to improve patient outcomes and patient safety.

-

For monitoring and improving transitions, standardized metrics related to these standards should be used in order to lead to continuous quality improvement and accountability.

The TOCCC then proposed the following standards:

-

Coordinating Clinicians

Communication and information exchange between the medical home and the receiving provider should occur in an amount of time that will allow the receiving provider to effectively treat the patient. This communication and information exchange should ideally occur whenever patients are at a transition of care; e.g., at discharge from the inpatient setting. The timeliness of this communication should be consistent with the patient’s clinical presentation and, in the case of a patient being discharged, the urgency of the follow-up required. Guidelines will need to be developed that address both the timeliness and means of communication between the discharging physician and the MH. Communication and information exchange between the MH and other physicians may be in the form of a call, voicemail, fax or other secure, private, and accessible means including mutual access to an EHR.

The emergency department (ED) represents a unique subset of transitions of care. The potential transition can generally be described as outpatient to outpatient or outpatient to inpatient depending on whether or not the patient is admitted to the hospital. The outpatient to outpatient transition can also encompass a number of potential variations. Patients with a medical home may be referred in to the ED by the medical home or they may self refer. A significant number of patients do not have a physician and self refer to the ED. The disposition from the ED, either outpatient to outpatient or outpatient to inpatient is similarly represented by a number of variables. Discharged patients may or may not have a medical home, may or may not need a specialist and may or may not require urgent (<24 hours) follow-up. Admitted patients may or may not have a medical home and may or may not require specialty care. This variety of variables precludes a single approach to ED transitions of care coordination.

-

Care Plans/Transition Record

The TOCCC proposed a minimal set of data elements that should always be part of the transition record and be part of any initial implementation of this standard. That list includes the following:

-

Principle diagnosis and problem list

-

Medication list (reconciliation) including over the counter/ herbals, allergies and drug interactions

-

Clearly identifies the medical home/transferring coordinating physician/institution and their contact information

-

Patient’s cognitive status

-

Test results/pending results

The TOCCC recommended the following additional elements that should be included in an “ideal transition record” in addition to the above:

-

Emergency plan and contact number and person

-

Treatment and diagnostic plan

-

Prognosis and goals of care

-

Advance directives, power of attorney, consent

-

Planned interventions, durable medical equipment, wound care etc

-

Assessment of caregiver status

-

Patients and/or their family/caregivers must receive, understand and be encouraged to participate in the development of their transition record which should take into consideration the patient’s health literacy, insurance status and be culturally sensitive.

-

Communication Infrastructure

-

All communications between providers and between providers and patients and families/caregivers need to be secure, private, HIPAA compliant, and accessible to patients and those practitioners who care for them.

Communication needs to be two-way with opportunity for clarification, and feedback. Each sending provider needs to provide a contact name and number of an individual who can respond to questions or concerns.

The content of information transferred needs to include a core standardized dataset.

This information needs to be transferred as a “living database” whereby it is created only once and then each subsequent provider then only needs to update, validate, or modify the information.

Patient information should be available to the provider prior to patient arrival

Information transfer needs to adhere to national data standards.

Patients should be provided with a medication list that is accessible (paper or electronic), clear, and dated.

-

Standard Communication Formats

Communities need to develop standard data transfer forms (templates, transmission protocols).

Access to the patient medical history needs to be on a current and ongoing basis with ability to modify information as a patient’s condition changes.

Patients, family and caregivers should have access to their information (“nothing about me without me”).

A section on the transfer record should be devoted to communicating a patients’ preferences, priorities, goals and values (e.g., patient does not want intubation).

-

Transition Responsibility

The sending provider/institution/team at the clinical organization maintains responsibility for the care of the patient until the receiving clinician/location confirms that the transfer and assumption of responsibility is complete (within a reasonable timeframe for the receiving clinician to receive the information i.e., transfers that occur in the middle of the night can be communicated during standard working hours). The sending provider should be available for clarification with issues of care within a reasonable timeframe after the transfer has been completed and this timeframe should be based on the conditions of the transfer settings. The patient should be able to identify the responsible provider. In the case of patients who do not have an ongoing ambulatory care provider or whose ambulatory care provider has not assumed responsibility, the hospital-based clinicians will not be required to assume responsibility for the care of these patients once discharged.

-

Timeliness

Timeliness of feedback and feed forward of information from a sending provider to a receiving provider should be contingent on four factors:

-

Transition settings

-

Patient circumstances

-

Level of acuity

-

Clear transition responsibility

This information should be available at the time of the patient encounter.

-

Community standards

Medical communities/institutions must demonstrate accountability for transitions of care by adopting national standards, and processes should be established to promote effective transitions of care

-

Measurement

For monitoring and improving transitions, standardized metrics related to these standards should be used. These metrics/measures should be evidence-based, address documented gaps and have demonstrated impact on improving care (comply with performance measure standards) whenever feasible. Results from measurement using standardized metrics must lead to continuous improvement of the transition process. The validity, reliability, cost, and impact, including unintended consequences, of these measures should be assessed and re-evaluated.

All of these standards should be applied with special attention to the varying transition settings and should be appropriate to each transition setting. Measure developers will need to take this into account when developing measures based on these proposed standards.

FUTURE CHALLENGES

In addition to the work on the principles and standards development, the TOCCC uncovered six future challenges which are described below.

Electronic Health Record

There was disagreement among the group as to the extent to which electronic health records would resolve the existing issues involved in poor transfers of care. However, the group did concur that (1) established transition standards should not be contingent upon the existence of an electronic health record (2) some universally, nationally defined set of core transfer information should be the short term target of efforts to establish electronic transfers of information

Use of a Transition Record

There should be a core set of data (much smaller than a complete health record or discharge summary) that goes to the patient and the receiving provider that includes items in the “core” record described above.

Medical Home

There was a lot of discussion around the benefits and challenges of establishing a medical home and inculcating the concept into delivery and payment structures. The group was favorable to the concept; however, since the medical home is not yet a nationally defined standard, care transition standards should not be contingent upon the existence of a “medical home.” Wording of future standards should use a general term for the clinician coordinating care across sites in addition to the term “medical home.” Using both terms will acknowledge the movement toward the medical home without requiring adoption of medical home practices to refine and implement quality measures for care transitions.

Pay for Performance

The group strongly agreed that behaviors and clinical practices are influenced by payment structures. Therefore, they agreed, a new principle should be established to advocate for changes in reimbursement practices to reward safe, complete transfers of information and care. However, development of standards and measures should move forward based on the current reimbursement practices and without assumptions of future changes.

Underserved/Disadvantaged Populations

Care transition standards and measures should be the same for all economic groups with careful attention that lower socioeconomic groups are not “forgotten” or unintentionally disadvantaged, including the potential for “cherry-picking.” It should be noted that underserved populations may not always have a “medical home” due to their disadvantaged access to the health system and providers. Moreover, clinicians who care for underserved/disadvantaged populations should not be penalized by standards that assume continuous clinical care and ongoing relationships with patients who may access the health system only sporadically.

Need for Patient-Centered Approaches

The group agreed that across all principles and standards previously established by Stepping Up to the Plate coalition, greater emphasis was needed on patient centered approaches to care including, but not limited to, including patient and families in care and transition planning, greater access to medical records, and the need for education at the time of discharge regarding self-care and core transfer information.

NEXT STEPS FOR THE TOCCC

The TOCCC focuses only on the transitions between the inpatient and outpatient settings and does not address the equally important transitions between the many other different care settings such as hospital to nursing home, or rehabilitation facility. The intent of the TOCCC is to provide this document to national measure developers such as the Physician Consortium for Performance Improvement and others in order to guide measure development and ultimately lead to improvement in quality and safety in care transitions.

References

Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, et al. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–7.

Roy CL, Poon EG, Karson AS, et al. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(2):121–8.

Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D, Min SJ. Posthospital medication discrepancies: prevalence and contributing factors. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165(16):1842–7.

Tsilimingras D, Bates DW. Addressing post-discharge adverse events: a neglected area. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(2):85–97.

Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, et al. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–41.

Nawar EW, Niska RW, Xu J. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2005 Emergency Department Summary. Advance Data From Vital And Health Statistics; No. 386. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2007.

Cooper JB. Do short breaks increase or decrease anesthetic risk? J Clin Anesth. 1989;1(3):228–31.

Cooper JB, Long CD, Newbower RS, Philip JH. Critical incidents associated with intraoperative exchanges of anesthesia personnel. Anesthesiology. 1982;56(6):456–61.

Wears RL, Perry SJ, Shapiro M, et al. Shift changes among emergency physicians: best of times, worst of times. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 47th Annual Meeting: p 1420–1423. Denver, CO: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society; 2003.

Wears RL, Perry SJ, Eisenberg E, et al. Transitions in care: signovers in the emergency department. Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 48th Annual Meeting: p 1625 - 1628. New Orleans, LA: Human Factors and Ergonomics Society; 2004.

Behara R, Wears RL, Perry SJ, et al. Conceptual framework for the safety of handovers. In: Henriksen K, ed. Advances in Patient Safety. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality/Department of Defense; 2005: pp 309 - 321.

Feldman JA. Medical errors and emergency medicine: will the difficult questions be asked, and answered? (letter). Acad Emerg Med.. 2003; 10(8):910–1.

Coleman EA, Berenson RA. Lost in transition: challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care. Ann Intern Med. 2004; 141(7):533–6.

Starfield B, Shi L. The Medical Home, Access to Care, and Insurance: A Review of Evidence. Pediatrics. 2004; 113(5 Supple):1493–8.

Redesigning the practice model for general internal medicine. A proposal for coordinated care: a policy monograph of the Society of General Internal Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(3):400–9.

The medical home. Pediatrics 2002;110(1 Pt 1):184-6.

American College of Physicians. The advanced medical home: a patient-centered, physician-guided model of healthcare. A Policy Monograph. 2006. Available at http://www.acponline.org/advocacy/where_we_stand/policy/adv_med.pdf Accessed March 13, 2009.

Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, et al. Development and testing of a measure designed to assess the quality of care transitions. Int J Integr Care. 2002;2:e02.

vom Eigen KA, Walker JD, Edgman-Levitan S, et al. Carepartner experiences with hospital care. Med Care. 1999;37(1):33–8.

Coleman EA, Mahoney E, Parry C. Assessing the quality of preparation for post hospital care from the patient’s perspective: the care transitions measure. Med Care. 2005;433:246–55.

American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Stepping Up to the Plate Alliance. Principles and Standards for Managing Transitions in Care (in press) Available at http://www.abimfoundation.org/publications/pdf_issue_brief/F06-05-2007_6.pdf Accessed March13, 2009.

Conflict of Interest Statements

Summary:

Conflict of Interest Statement for Faculty, Authors, Members of Planning Committees and Staff

American College of Physicians – Society of Hospital Medicine – Society of General Internal Medicine

The following members of the Steering (or Planning) Committee and Staff of the Transitions of Care Consensus Conference have declared a Conflict of Interest:

Dennis Beck, MD, FACEP (ACEP Representative) President and CEO, Beacon Medical Services has declared conflict of interest of Stocks/Holdings: 100 units of stock options/holdings in Beacon Hill Medical Services

Tina Budnitz, MPH (SHM Staff) Senior Advisor for Quality Initiatives Society of Hospital Medicine has declared conflict of interest of Employment: Staff, Society of Hospital Medicine

Eric S. Holmboe, MD (ABIM Representative) Senior Vice President Quality Research and Academic Affairs American Board of Internal Medicine has declared conflict of interest of Employment: SVP Quality Research and Academic Affairs American Board of Internal Medicine

Vincenza Snow, MD, FACP (ACP Staff) Director, Clinical Programs and Quality of Care American College of Physicians has declared conflict of interest of Research grants: CDC, Atlantic Philanthropies, Novo Nordisk, Bristol Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, United Healthcare Foundation, Sanofi Pasteur

Laurence D. Wellikson, MD, FACP (SHM Staff) Chief Executive Officer Society of Hospital Medicine has declared conflict of interest of Employment: CEO, Society of Hospital Medicine

Mark V. Williams, MD, FACP (Co-Chair, SHM Representative) Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Hospital Medicine Past-President, Society of Hospital Medicine has declared conflict of interest of Membership: Society of Hospital Medicine

The following members of the Steering (or Planning) Committee and Staff of the Transitions of Care Consensus Conference have declared No Conflict of Interest:

David Atkins, MD, MPH, (AHRQ Representative)

Associate Director, QUERI, Department of Veteran Affairs, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research & Development (124)

Doriane C. Miller, MD (Co-Chair, SGIM Representative)

Associate Division Chief, General Internal Medicine, Stroger Hospital of Cook County

Jane Potter, MD (American Geriatric Society Representative)

Professor and Chief of Geriatrics, University of Nebraska Medical Center

Robert L. Wears, MD, FACEP (Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Representative)

Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Florida

Kevin B. Weiss, MD, MPH, MS, FACP (Chair, ACP Representative)

CEO, American Board of Medical Specialties

Financial Support Statement

The TOCCC was funded under an unrestricted educational grant from Novo Nordisk, as part of the ACP Diabetes Initiative, and from the AHRQ. The funders had no input into the planning, structure, content, participants, or outcomes of the conference.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

APPENDIX: CONFERENCE DESCRIPTION

In the Fall-Winter of 2006 the Executive Committees of the American College of Physicians (ACP), the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM), and the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) agreed to jointly develop a policy statement on transitions of care. Transitions of care specifically between the inpatient and outpatient settings was selected as an ideal topic for collaboration for the three societies as they represent the continuum of care for internal medicine within these settings. To accomplish this, the three organizations decided to convene a consensus conference to develop consensus guidelines and standards around transitions between inpatient and outpatient settings through a multi-stakeholder process. A steering committee was convened, chaired by Kevin B. Weiss, MD, MPH, FACP of the ACP and co-chaired by Doriane Miller, MD, representing the SGIM; and Mark Williams, MD, FACP representing the SHM. The steering committee also had representatives from the AHRQ, ABIM and AGS. The steering committee developed the agenda and invitee list for the Consensus Conference. After the conference was held the steering committee was expanded to include representation from the emergency medicine community. The American College of Emergency Physicians was represented by Dr. Dennis Beck and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine was represented by Dr. Robert Wears.

During the planning stages of the Transitions of Care Consensus Conference (TOCCC), the steering committee became aware of the Stepping Up to the Plate (SUTTP) Alliance of the ABIM Foundation. The SUTTP Alliance has representation from medical specialties such as internal medicine and its subspecialties, family medicine, and surgery. The Alliance formed in 2006 and has been working on care coordination across multiple settings and specialties. The SUTTP developed a set of principles and standards for care transitions and agreed to provide their draft document to the TOCCC for review, input, and further development and refinement.

The TOCCC was held over two days on July 11-12, 2007 at ACP Headquarters in Philadelphia, PA. There were 51 participants representing over thirty organizations. Participating organizations included medical specialty societies from internal medicine as well as family medicine and pediatrics, governmental agencies, such as the AHRQ and CMS, performance measure developers, such as the NCQA and AMA PCPI, nurses associations, such as the VNAA and Home Care and Hospice, pharmacists groups, and patient groups such as the Institute for Family-Centered Care. The morning of the first day was dedicated to presentations covering the AHRQ Stanford Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) Evidence Report on Care Coordination, the literature around transitions of care, the continuum of measurement from principles to standards to measures, and the SUTTP principles document. The attendees then split into breakout groups that discussed the principles and standards developed by the SUTTP and refined and/or revised them. All discussion were summarized and agreed on by consensus and presented by the breakout groups to the full conference attendees. The second day was dedicated to reviewing the work of the breakout groups and further refinement of the principles and standards through a group consensus process. Once this was completed, the attendees then prioritized the standards using a group consensus voting process. Each attendee was given one vote and each attendee attached a rating of 1 for highest priority and 3 for lowest priority to the standards. The summary scores were then calculated and the standards were then ranked from those summary scores.

The TOCCC recognizes that full implementation of all of these standards may not be feasible and that these standards may be implemented in a stepped or incremental basis. This prioritization can assist in deciding which of these to implement. The results of the prioritization exercise are:

-

1.

All transitions must include a transition record

-

2.

Transition Responsibility

-

3.

Coordinating Clinicians

-

4.

Patient and Family involvement and ownership of the transition record

-

5.

Communication Infrastructure

-

6.

Timeliness

-

7.

Community Standards

The final activity of the conference was to discuss some of the overarching themes and environmental factors that could influence the acceptance, endorsement, and implementation of the standards developed. The TOCCC adjourned with the tasks of forwarding its conclusions to the SUTTP Alliance and to develop a policy document to be reviewed by other stakeholders not well represented at the conference. Two such pivotal organizations were the American College of Emergency Physicians and the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine that were added to the Steering Committee after the conference. Subsequently the ACP, SGIM, SHM, AGS, ACEP, and SAEM approved the summary document and forwarded it to the other participating organizations for possible endorsement and to national measures and standards developers for use in performance measurement development.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Snow, V., Beck, D., Budnitz, T. et al. Transitions of Care Consensus Policy Statement American College of Physicians-Society of General Internal Medicine-Society of Hospital Medicine-American Geriatrics Society-American College of Emergency Physicians-Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J GEN INTERN MED 24, 971–976 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-0969-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-0969-x