ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Coordination across a patient’s health needs and providers is important to improving the quality of care.

OBJECTIVES

(1) Describe the extent to which adults report that their care is coordinated between their primary care physician (PCP) and specialists and (2) determine whether visit continuity with one’s PCP and the PCP as the referral source for specialist visits are associated with higher coordination ratings.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional study of the 2007 Health Tracking Household Survey.

PARTICIPANTS

A total of 3,436 adults with a PCP and one or more visits to a specialist in the past 12 months.

MEASUREMENTS

Coordination measures were patient perceptions of (1) how informed and up to date the PCP was about specialist care received, (2) whether the PCP talked with the patient about what happened at the recent specialist visit and (3) how well different doctors caring for a patient’s chronic condition work together to manage that care.

RESULTS

Less than half of respondents (46%) reported that their PCP always seemed informed about specialist care received. Visit continuity with the PCP was associated with better coordination of specialist care. For example, 62% of patients who usually see the same PCP reported that their PCP discussed with them what happened at their recent specialist visit vs. 48% of those who do not usually see the same PCP (adjusted percentages, p < 0.0001). When a patient’s recent specialist visit was based on PCP referral (vs. self-referral or some other source), 50% reported that the PCP was informed and up to date about specialist care received (vs. 35%, p < 0.0001), and 66% reported that their PCP discussed with them what happened at their recent specialist visit (vs. 47%, p < 0.0001).

CONCLUSIONS

Facilitating visit continuity between the patient and PCP, and encouraging the use of the PCP as the referral source would likely enhance care coordination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

This study assesses whether continuity of care and referral source are associated with better coordination of care from the patient perspective. Primary care and care coordination conceptual frameworks1,2 suggest that these aspects of care are important to coordination; however, data linking these primary care processes with better coordination for adults are less plentiful in the literature than one might expect.

Coordination of care is a defining component of primary care.1,3 Common to most definitions of coordination is the degree to which information from various sources is recognized and incorporated into a patient’s current care.1–3 This includes communication between the primary care physician (PCP) and the other specialists a patient sees, and between the PCP and the patient, in order to integrate specialists’ recommendations in a way that is clinically appropriate, understandable to the patient, and consistent with the patient’s needs. Coordination between referring physicians and specialists is highly valued by patients4,5 and is associated with higher quality care, enhanced referral completion, greater physician satisfaction with specialty care, and use of recommended preventive services.1,2,6,7 PCPs, working with their staff as a team, are well positioned to lead coordination of care for patients given their generalist training and knowledge across different body systems and conditions, expertise in managing comorbid conditions, and ongoing relationship with a patient over time.1,3,6,8

Yet, referring clinicians and specialists exchange information less frequently than necessary, and this has adverse consequences for patients.2,7 This aspect of coordination has been examined within particular health systems9,10 in samples of primary care clinics and physicians7,11 and in an international study of health systems,12 with less coordination being associated with poorer patient outcomes, duplication of services,6,9,13 lower provider satisfaction, less efficiency, and lower patient ratings of physicians.5,7,11 Analyses of Medicare claims data also suggest that care is highly fragmented across physicians, in particular for patients with chronic conditions.14

Since patients are the parties experiencing care first-hand from multiple providers (e.g., only the patient was present in both the specialist’s and PCP’s office), they are uniquely positioned to assess particular aspects of coordination. Examples of such aspects of coordination include: (1) whether the primary care physician is informed of care the patient received from an outside specialist, (2) whether the PCP discussed with the patient what happened at the most recent visit to the specialist, and (3) whether different doctors caring for a patient’s chronic condition work well together to coordinate that care (e.g., in a way that avoids conflicting advice to the patient).

Using a nationally representative population-based sample of adults across a range of demographic, geographic, and insurance characteristics, we (1) describe the extent to which adults report that their care is coordinated between their primary care physician (PCP) and specialists and (2) determine whether visit continuity with one’s PCP and specialist referral source were associated with higher ratings of coordination.

METHODS

Study Population and Data

The data source for this analysis is the 2007 Health Tracking Household Survey, a nationally representative survey of the civilian noninstitutionalized US population. Funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the 2007 survey is the fifth in a series of household surveys that have been conducted since 1996 (previously known as the Community Tracking Study Household Survey). All interviews were conducted by telephone, in English or Spanish, with a random-digit dialing (RDD) sample selection method. The survey collected detailed information on health insurance, health services use, access to care, health status and chronic conditions, and perceptions of quality of care. Details on the survey methodology, including its clustered sampling design, can be found at (http://www.hschange.org/CONTENT/757/757.pdf).15

The survey’s response rate (43%) takes into account families who were contacted and refused to participate and households with whom contact was not made. Population weights used to produce nationally representative estimates adjust for differential nonresponse based on age, gender, race/ethnicity, and education. The response rate is consistent with other recent population-based national RDD telephone surveys,16 which in general have had declining response rates over the past 10 years. Although lower response rates increase concerns about survey bias, methodological studies on earlier survey rounds with higher response rates strongly suggest that the lower response rate has not increased the bias of survey estimates, especially after adjustments to population weights that account for nonresponse bias.17

The total sample for the survey was 17,797 persons, including 15,197 adults. Our analysis did not include the 2,600 persons under age 18 from the sample. So few children had a specialist visit, it was not an efficient use of resources to ask them the coordination items because there would have been insufficient power to analyze coordination in that group.

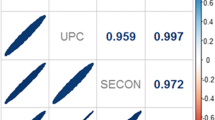

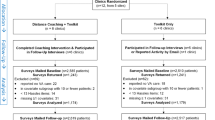

The two objectives of this analysis were to describe patients’ ratings of coordination of care between their PCP and specialist(s) they had seen in the past 12 months and to determine whether continuity of care and referral source were linked with those ratings. Thus, our analyses focus primarily on the subgroup of adults with a usual PCP and a visit to a physician specialist in the previous 12 months, with completed responses to the items on coordination of care (n = 3,436) (Fig. 1).

Measures

Establishing Usual Source of Care and Specialty Care Use

Question flow and content are summarized in Figure 1. Survey items and lay person’s definitions of terms used in those items (e.g. primary care physician, specialist, coordination of care, chronic disease definitions) come from previously validated surveys.18–21

Measures of Care Coordination

Coordination items were adapted from validated surveys19–21 and underwent cognitive interview testing to ensure that respondents understood and felt capable of answering the items. The first two outcomes focused on the components of coordination that relate to communication and recognition of specialists’ recomendations by the PCP and back to the patient. Our third coordination measure assessed the extent to which different physicians caring for a patient’s chronic conditions work together to co-manage care. The first two outcome measures were: (1) “In the last 12 months, how often did your usual physician seem informed and up to date about the care you got from specialists?” Response options were: never, almost never, sometimes, usually, almost always, always, and don’t know/refused. (2) “After going to the most recent specialist visit, did your usual doctor talk with you about what happened at the visit with the specialist?” Response options were: yes, no.

The third coordination measure was preceded by ascertaining whether respondents had been told by a health professional that they had 1 or more of the 11 most prevalent chronic conditions.18 Patients who responded affirmatively to any of the 11 chronic conditions (n = 1,650) were asked whether they had seen a doctor or other health professional for that particular condition, and then were asked the question used to create our third outcome measure: “How well do the different doctors that see you for your [chronic condition] coordinate your care? By care coordination, we mean how well do your doctors work together to manage your health care?” Response options included: My care is…not coordinated at all, coordinated some of the time, coordinated most of the time, and coordinated all of the time.21 If a respondent had more than one chronic condition and their ratings of the quality of co-management between their physicians was the same, the patient was assigned that value for this outcome variable. If the respondent’s quality of co-management was reported to be different for their separate conditions, then the conditions were ranked in the order listed above based on clinical judgment and prior data14 on the extent to which each condition on average poses greater coordination burden and need for co-management; the condition listed highest was the one used to create that co-management variable for that respondent. There were insufficient numbers of respondents with individual conditions to analyze conditions separately.

Independent variables of primary interest were visit continuity (whether the patient usually sees the same physician at the practice for primary care visits) and referral source for the most recent specialist visit (PCP vs. some other source such as self-referral or cross-referral from one specialist to another). The variable on continuity of primary care visits with the same individual was subjective and was based on the survey question: “Do you usually see the same doctor each time you go there?”

Controlling variables prior literature1–3,10,22 indicates could potentially influence or confound patient access to care, perceptions, and ratings of care coordination included: patient age, sex, education, income, race/ethnicity, interview language, self-assessed health status, number of chronic conditions, number of specialists seen in the past 12 months, insurance coverage and type, HMO participation, PCP’s practice setting, urban/rural location, the patient’s activation score (how active a role a patient plays in his/her own health care),23 and the ratio of primary care to specialist physicians in a respondent’s county.

Statistical Analysis

Both unadjusted and adjusted results are presented with sample frequencies and population-based weighted estimates. Associations were measured in bivariate analyses using x2 tests. A separate regression model was created for each of the three coordination outcomes. These models were also repeated on just the subgroup with the seven prevalent chronic conditions that were most likely to require coordination (hypertension, coronary heart disease, diabetes, depression, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma). All models were estimated using SUDAAN software24 (version 9.0.1) to adjust the standard errors for the effects of clustering within households and for the complex sample design. For the logistic regression analyses, adjusted percentages are presented along with odds ratios and 95% confidence limits. Tests of statistical significance and adjusted percentages are based on the underlying logit coefficients.

RESULTS

Compared to the entire sample, the subgroup with a usual PCP and a visit to a specialist in the previous 12 months was on average older, had higher income, and was more likely to be in fair or poor health status (Table 1). Among people under age 65, those with a visit to a specialist in the previous 12 months were more likely to have private insurance. There were no differences between persons with and without a specialist visit in terms of primary language, patient activation scores, rural/suburban/urban residence, or county ratio of primary care to specialist physicians (thus data not shown).

Among respondents with a PCP and one or more specialist visits in the previous 12 months, 93% usually saw the same PCP for their primary care visits (vs. 70% for the entire household adult sample). Seventy-two percent of those with a recent specialist visit indicated that the specialist was identified by their PCP (Table 1).

Less than half of respondents (46%) reported that their PCP always seemed informed about care received from specialists (Table 2). Two thirds (62%) reported that after going to the specialist, their PCP talked with them about what happened at that most recent specialist visit. In terms of how well different doctors work together to manage a patient’s chronic condition, 44% said they coordinated “all of the time.”

Coordination of care varied by patient characteristics (Table 3). Persons over 65 years were more likely to rate their coordination highly. There were no differences in coordination ratings by income, race and ethnicity, or primary language (thus data not shown). Patients who were more activated (in terms of playing a role in their own care23) rated their coordination more highly than did less activated persons. Persons 65 years and over with both Medicare and Medicaid rated their coordination higher than those with Medicare alone.

Compared to patients with less continuity, those who saw the same PCP for most primary care visits were more likely to report that their PCP was informed about care received from specialists and that the PCP discussed what happened at their most recent specialist visit (Tables 3 and 4). When patients’ visits to a specialist were based on PCP referral rather than from some other source, patients were significantly more likely to report that the PCP was informed and up to date about care received from the specialist (50% vs. 35%, adjusted percentages, p < 0.0001) and that their PCP discussed with them what happened at the specialist visit (66% vs. 47%, p < 0.0001). Among the subgroup with any of the seven chronic conditions, those whose most recent specialist visit was based on PCP referral had significantly higher ratings for all three aspects of coordination, including co-management by different physicians (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

We found that the majority of patients with a specialist visit in the past 12 months report less than ideal coordination between their PCP and the specialist. Continuity of visits with the same PCP and PCP as referral source were each independently associated with higher ratings of care coordination. Among persons with chronic conditions, the association between PCP as referral source and each of the three coordination outcomes was even more pronounced.

Continuity of visits with the same clinician has been linked with better coordination in a pediatric population.25 Our finding that visit continuity with the same PCP was associated with better coordination for adults adds to this prior work among children.

Assessment of additional factors associated with better coordination between primary care and specialist physicians in the literature to date comes predominantly from physician surveys and chart reviews. Such data revealed that improvements in the referral process and its completion, as well as physician satisfaction with the referral process, result from the PCP making the appointment with the specialist, the PCP sending the specialist information about the referral, and the specialist providing feedback to the PCP that include plans for co-management.7 A survey of PCPs and their patients identified continuous telephone access, the presence of agreements with other health care providers, and the performance of more services within the PC office as being associated with higher levels of coordination between PCPs and specialists.22 To this prior work, we add the finding that coordination of care between PCP and specialists is much better, from the patient perspective, when the PCP is the referral source.

Rates of patient self-referral vary with patient age, insurance, local market factors, and health status. Among persons under age 65 in three points of service plans, self-referral rates were on the order of 17% to 30%.26 Among Medicare beneficiaries, self-referral rates are much higher, with some estimates of patient self-referrals to specialists as high at 70%.27 Despite the prevalence of self-referral, patients do not always feel that they have the awareness of when a referral is clinically indicated or appropriate. Patients value the first contact and coordination roles of PCPs, and find PCP participation helpful in deciding to see a specialist.30 Given the high rates of self-referral, associated fragmentation of care, and associated costs of greater use of specialists,28 efforts to improve care coordination might take into account the benefit of having a PCP as the referral source as identified by patients in this study.

While continuity of visits with one’s PCP, and PCP as referral source, were associated with substantially higher ratings of coordination of specialist care, there is clearly room for improvement. For example, even when patients’ most recent visit to a specialist was based on PCP referral rather than self-referral, only 50% of the patients reported that the PCP was always informed about care received from the specialist. Communication between the PCP and consulting specialists likely needs to be increased from both directions, and sharing of the results of such communications with patients likely also requires additional attention. Deficiencies in consultant communication back to PCPs have been widely documented.1,11 Thus, achieving maximal coordination will likely require efforts that target specialists as well. Incentives for two-way communication are currently lacking in our fee-for-service reimbursement system, with a negative impact on coordination of care for patients.

Limitations of our study include that most measures were patient self-reported; thus, there is the potential for bias in that patients who value coordination more highly may also do more to inform their PCP of their desire to visit a specialist, or may participate more actively in organizing their care. We attempted to control for this potential bias by including a validated measure of how much patients actively participate in their own care.23 It is also possible that patient’s may over-estimate the extent of coordination by their providers. In an attempt to adjust for the “coordination burden” a patient might require, we adjusted for the number of chronic conditions, the patient’s health status, and whether s/he saw more than one specialist in the past 12 months. However, we were not able to adjust for the total number of visits to specialists in the past 12 months because we do not have access to respondents’ claims data, and, patient recall of the annual number of visits by provider type has been demonstrated by others to be poor.29 Finally, these data are cross-sectional; thus, it is not possible to ascertain causality.

Implications

Decision makers want practical advice on how to improve coordination of care.2 Our nationally representative study demonstrated that coordination is better, from the patient perspective, when patients see the same PCP for most of their primary care visits and when specialist referrals are made by the PCP rather than by another means.

Our findings can help inform current efforts to develop and finance medical homes by taking into account the roles that visit continuity with the same PCP and PCP as the referral source have on better coordination of care as rated by patients. This information can inform efforts to create educational messages for patients, and incentives for patients and providers. Patients can be encouraged to see the same PCP for as many of their visits as possible, when scheduling and access needs permit; provider appointment and scheduling systems can be structured in a way to facilitate this.

Patients can also be engaged in a discussion or voluntary agreement with their PCP about the benefits of having a PCP as their coordinator and referral source, as opposed to engaging in self-referrals or cross-referrals from one specialist to another. On the specialist side, specialists might be encouraged by payers to both communicate back to a patient’s PCP and to inform a patient’s PCP of cross-referrals they make. Encouraging patients to obtain referrals to specialists from their PCPs need not necessarily take the form of mandatory gate-keeping. A study of point-of-service health plan enrollees found that simply having the option to self-refer was enough for enrollees.26 Thus, encouraging patients and physicians to voluntarily coordinate referrals within the medical home (rather than imposed gate-keeping) may be sufficient to enhance coordination of care.

Finally, our findings have implications for efforts to foster health care “consumerism”–broadly defined as consumers taking more responsibility for medical costs, lifestyle choices, and treatment decisions. Some observers propose financial incentives for consumers to “shop” for physicians and hospitals through the use of comparative cost and quality information. An unintended consequence of increased “shopping” for physicians could be an increase in self-referrals to specialists by patients who want to avoid the cost of a primary care visit. Others have found that patients do not always feel that they have the awareness of when a referral is indicated, and they find PCP participation helpful in deciding whether to see a specialist.30 Thus, efforts to engage patients in consumerism might consider our findings that patients perceive their coordination to be better when they have continuity of care with the same PCP and when their referrals to specialists were based on PCP recommendation.

REFERENCES

Starfield B. Primary care: Balancing health needs, services and technology. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998:438.

McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, et al. Care Coordination. Vol 7 of: Shojania KG, McDonald KM, Wachter RM, Owens DK, editors. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies. Technical review No. 9 (Prepared by the Stanford University-UCSF Evidence-based Practice Center under contract 290-02-0017). AHRQ Publication No. 04(07)-0051-7. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. June 2007.

Institute of Medicine. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. 1996. National Academy Press, Washington D.C., 395 pp.

Laine C, Davidoff F, Lewis CE, et al. Important elements of outpatient care: a comparison of patients’ and physicians’ opinions. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:640–5.

Anderson R, Barbara A, Feldman S. What patients want: A content analysis of key qualities that influence patient satisfaction. J Med Pract Manage. 2007;22(5):255–61.

Stille CJ, Jerant A, Bell D, Meltzer D, Elmore JG. Coordinating care across diseases, settings and clinicians: a key role for generalist in practice. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:700–8.

Forrest CB, Glade GB, Baker AE, Bocian A, von Schrader S, Starfield B. Coordination of specialty referrals and physician satisfaction with referral care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154:499–506.

Bodenheimer T, Lo B, Casalino L. Primary care physicians should be coordinators, not gatekeepers. JAMA. 1999;281:2045–9.

Parchman ML, Noël PH, Lee S. 2005 Primary care attributes, health care system hassles, and chronic illness. Med Care. 2005;11:1123–9.

Safran DG, Tarlov AR, Rogers WH. Primary care performance in fee-for-service and prepaid health care systems. Results from the medical outcomes study. JAMA. 1994;271:1579–86.

Cummins RO, Smith RW, Inui TS. Communication failure in primary care, Failure of consultants to provide follow-up information. JAMA. 1980;243:1650–2.

Schoen C, Osborn R, Doty MM, Bishop M, Peugh J, Murukutia N. Toward higher-performance health systems: adults’ health care experiences in seven countries, 2007. Health Aff (Millwood). 2007; Nov-Dec: w717-34.

Audet AM, Davis K, Schoenbaum SC. Adoption of Patient-Centered Care Practices by Physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:754–9.

Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) Report to Congress. Increasing the Value of Medicare. Chapter 2, “Care Coordination in Fee-for service Medicare,” June 2006:31-56.

http://www.hschange.org/CONTENT/757/757.pdf; Household Survey Methodology report Round 4 (2007), and the Round 5 (2008). Accessed November 18, 2008.

Johnson DR, Addressing the Growing Problem of Survey Nonresponse. http://www.ssri.psu.edu/survey/Nonresponse1.ppt. Accessed November 18, 2008.

Carlson BL, Strouse R. The Value of the Increasing Effort to Maintain High Response Rates in Telephone Surveys. In American Statistical Association, 2005 Proceedings of the Section on Survey Research Methods. Alexandria, VA: American Statistical Association; 2005 August.

National Health Interview Survey, NHIS. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/nhis/hisdesc.htm. Accessed June 11, 2008.

CAHPS Clinician and Group Adult Survey. http://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/Browse/DisplayOrganization.aspx?org_id = 9&doc = 746. Accessed June 11, 2008.

Adult Primary Care Assessment Tool, Starfield B. Johns Hopkins University 1998; http://www.jhsph.edu/hao/pcpc/tools.htm, last accessed June 11, 2008.

Safran DG, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR, et al. The Primary Care Assessment Survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Med Care. 1998;36(5):728–39 May.

Haggerty JL, Pineault R, Beaulieu M, et al. Practice features associated with patient-reported accessibility, continuity, and coordination of primary health care. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:116–23.

Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and Measuring Activation in Patients and Consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39:1005–26.

Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN Language Manual, Release 9.0.1. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2005.

Christakis DA, Wright JA, Zimmerman FJ, Bassett AL, Connell FA. Continuity of care is associated with well-coordinated care. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3:82–6.

Forrest CB, Weiner JP, Fowles J, et al. Self-referral in point-of-service health plans. JAMA. 2001;285:2223–31.

Shea D, Stuart B, Vasey J, Nag S. Medicare physician referral patterns. Health Serv Res. 1999;34:331–48.

Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:273–87.

Wolinsky FD, et al. Hospital episodes and physician visits: the concordance between self-reports and Medicare claims. Med Care. 2007;45:300–7.

Grumbach K, Selby JV, Damberg C, et al. Resolving the gatekeeper conundrum what patients value in primary and referrals to specialists. JAMA. 1999;282:261–6.

Acknowledgement

This study and the 2007 Health Tracking Household Survey were funded entirely by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their feedback on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

O’Malley, A.S., Cunningham, P.J. Patient Experiences with Coordination of Care: The Benefit of Continuity and Primary Care Physician as Referral Source. J GEN INTERN MED 24, 170–177 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0885-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0885-5