Abstract

Very little is known about complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use in Asian Americans (AA), especially on a national level. To compare CAM use, reasons for use, and disclosure rates between Asian and non-Hispanic white Americans (NHW), and examine ethnic variations among AA. Data on CAM use in the past year (excluding prayer) were used from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey for 917 AA and 20,442 NHW. Compared with NHW, AA were as likely to use any CAM modality [42 vs. 38%; adjusted prevalence ratio = 1.09, 95% confidence interval (0.94, 1.27)]. Asian Americans were less likely than NHW to disclose the use of herbal medicines (16 vs. 34%, p < 0.001) and mind/body therapies (15 vs. 25%, p < 0.05). Mind/body therapies were used more often by Asian Indians (31%) than by Chinese (21%) and Filipinos (22%), whereas herbal medicines were used more often by Chinese (32%) than by Filipinos (26%) and Asian Indians (19%). Among AA, CAM use was associated with being female, having higher education, and having a chronic medical condition; foreign-birth was not associated with CAM use. Complementary and alternative medicine use is common among AA, and there are important ethnic variations in use. Asian Americans are less likely than NHW to disclose CAM use to conventional healthcare providers, suggesting that it is particularly important that physicians query AA patients about CAM use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is defined by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine as a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine.1 Results from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) indicated that 62% of adults used some form of CAM therapy during the previous 12 months. The most commonly used modalities included prayer, meditation, chiropractic care, yoga, and massage.

Projections from the U.S. Census Bureau indicate that Hispanic and Asian Americans (AA) are the fastest growing minority groups in the United States.2 However, very few studies have examined CAM use among ethnic populations. Graham et al.3 found that Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks used CAM less often than non-Hispanic whites (NHW), based upon analysis of the 2002 NHIS survey. Even fewer studies have examined CAM use nationally among AA. Ahn et al.4 found that 55 to 72% of Chinese and Vietnamese populations had ever used CAM, and that use of CAM modalities varied across Asian ethnic groups. Moreover, CAM use by Asian ethnic groups is poorly characterized.

Given this paucity of information, we used the 2002 NHIS to estimate national rates of CAM use among AA, and compared CAM rates with NHW. We further explored whether reasons for CAM use and rates of disclosure to healthcare providers differed between AA and NHW. Finally, we examined patterns of CAM use by the three largest Asian ethnic groups (Chinese, Filipino, Asian Indian) represented in the NHIS.

METHODS

Data Source

We analyzed data from the 2002 NHIS Sample Adult Core and the Alternative Medicine Supplement. The NHIS is a multipurpose health survey conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and is the principal source of information on the health of the civilian, noninstitutionalized, household population of the United States. Households were randomly selected based upon a multistage stratified sampling design. Face-to-face surveys were administered in English and/or Spanish. One randomly selected adult, aged 18 years or older, from each household in the sample was asked to complete the Sample Adult and Alternative Medicine questionnaires. Hispanic and non-Hispanic black populations were oversampled. The final adult sample included 31,044 respondents, with an overall response rate of 74%. We used data from 917 AA and 20,442 NHW respondents.

Respondents were queried about their use of 21 CAM modalities (excluding prayer). Our primary outcome of interest was the use of at least one of the 21 CAM modalities in the previous 12 months. Small sample sizes precluded analyses of many modalities individually. Therefore, we grouped the 21 CAM modalities into five broad categories: alternative medical systems (Ayurveda, acupuncture, homeopathy, folk medicine, naturopathy), bodywork therapies (chiropractic care, massage), biologically-based therapies (diet-based therapies, mega-vitamin therapy, chelation therapy), mind/body therapies (biofeedback, energy healing, hypnosis, tai chi, qigong, meditation, guided imagery, progressive relaxation, deep breathing, yoga), and herbal medicines.

For each CAM modality used in the past year, respondents were asked a series of questions to gather information about disclosure to conventional providers and reasons for CAM use. Disclosure was ascertained using the following question: “Did you let any of these conventional medical professionals (medical doctor, nurse practitioner/physician assistant, psychiatrist) know about your use of [modality]?” Reasons for use were ascertained using the following questions. First, respondents were asked “Did you use [modality] to treat a specific health problem or condition?” Second, they were asked “Did you choose [modality] for any of the following reasons?” Respondents answered yes/no to each of five items: (1) conventional medical treatments would not help you, 2) conventional medical treatments were too expensive, (3) [modality] combined with conventional medical treatments would help you, (4) a conventional medical professional suggested you try [modality], or (5) you though it would be interesting to try [modality]. Lastly, respondents were asked “How important was your use of [modality] to maintain health and well-being?” We categorized responses as very important or not very important.

We identified potential correlates of CAM use from previous literature, including sociodemographic characteristics, health care access, and illness burden. Sociodemographic characteristics included respondent’s age (18–24, 25–44, 45–64, or ≥65 years); sex; educational attainment (<high school, high school graduate, college graduate or higher); region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South, West); annual family income (<$20,000, $20,000–$44,999, $45,000–$74,999, ≥$75,000); place of birth (U.S.-born, foreign-born); and, for foreign-born respondents, the number of years in the United States (<5, 5–10, >10). Health care access was measured by insurance status (uninsured, Medicaid, Medicare, private, other) and access to conventional health care (e.g., clinic, doctor’s office, emergency department). Disease burden was measured by self-rated health status (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor), body-mass index (BMI) (<25 kg/m2, ≥25 kg/m2), and number of self-reported chronic medical conditions (none, 1, ≥2).

Statistical Analysis

The Institutional Review Boards at our institutions approved this study. All analyses used SAS-callable SUDAAN version 8.1 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC, United States) to obtain proper variance estimates that account for the complex sampling design. All results were weighted to reflect national estimates. We used bivariable analyses to describe the study sample, and compare characteristics between AA and NHW respondents. Next, we used methods of Flanders and Rhodes 5 to estimate prevalence of CAM use, adjusted for age, sex, education, income, region, place of birth, insurance status, access to conventional health care, BMI, self-rated health status, and number of chronic medical conditions, for AA and NHW separately. We present prevalence estimates for each characteristic adjusted for the other factors. In addition, we estimated the adjusted prevalence ratio (aPR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of CAM use in past 12 months for AA compared to NHW.

Next, we estimated age–sex-adjusted disclosure rates for herbal, mind/body, and bodywork therapies separately, and compared rates between AA and NHW. Insufficient sample sizes precluded analyses of disclosure for alternative systems and biologically based therapies. We then compared reasons for use by race/ethnicity to identify differences in CAM use for treatment of specific medical conditions and maintaining health and well-being. Insufficient sample sizes precluded analyses of reasons for use for alternative systems, biologically-based therapies, and bodywork therapies. Finally, we further examined the subset of AA to (1) explore ethnic variations in age–sex adjusted prevalence of CAM use for the three largest Asian ethnic groups surveyed (Asian Indian, Chinese, and Filipino) and (2) identify independent correlates of any CAM use among AA using multivariable logistic regression.

RESULTS

Table 1 identifies respondent characteristics. We found significant differences between AA and NHW in sociodemographic characteristics (age distribution, sex, education levels, and region of residence), health care access (insurance status and access to conventional healthcare), and disease burden (self-rated health, number of chronic conditions, and BMI). In particular, AA were younger, more educated, and more likely to live in the west. They reported fewer chronic conditions and a lower BMI. Overall, 80% of AA were foreign-born, and two-thirds had lived in the United States for more than 10 years.

Prevalence of CAM Use During the Past 12 Months

Overall, 42% of AA and 38% of NHW reported using at least one CAM modality in the past year (p = 0.06) (Table 2). After adjustment for sociodemographic characteristics, health care access, and illness burden, AA were as likely to use CAM as NHW [aPR = 1.09, 95% CI (0.94, 1.27)].

Table 2 presents age–sex-adjusted prevalence rates for AA and NHW during the past 12 months for the categories of CAM. Use of mind/body therapies and herbal medicines was common in both groups, whereas alternative systems and biologically based therapies were rarely used. Compared with NHW, AA used herbal medicine more often (19 vs. 25%; p < 0.01) and bodywork therapies less often (13 vs. 7%; p < 0.001).

Table 3 presents the prevalence of CAM use during the past 12 months among AA and NHW for selected characteristics. For both groups, CAM users were more often female, had higher education levels, and had one or more chronic conditions. Compared with their NHW counterparts, AA who were 65 years and older reported higher CAM use (p < 0.01). Asian Americans who reported having more than one chronic medical condition reported higher CAM use than NHW respondents (p < 0.001). Among AA, those with family incomes greater than $75,000 reported higher rates of CAM use. For both groups, CAM use varied by region and insurance status, although the patterns of use differed between them. Contrary to our hypothesis, there was no significant difference in CAM use between U.S.-born and foreign-born AA.

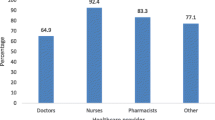

Disclosure of CAM Use to Healthcare Providers

Asian Americans disclose the use of any CAM modality less often than NHW (25 vs. 40%; p < 0.001). Compared to NHW, AA were substantially less likely to disclose the use of herbal medicines (34 vs. 16%; p < 0.001) and mind/body therapies (25 vs. 15%; p < 0.05) to their conventional health care providers. Disclosure of bodywork therapies was higher for both groups and not significantly different (38 vs. 44%; p = 0.70).

Reasons for CAM Use

Compared with NHW, AA used mind/body therapies less frequently to treat specific medical conditions (33 vs. 20%; p < 0.01), but more frequently reported that mind/body therapies were very important to health maintenance and well-being (31 vs. 43%; p < 0.05).

Asian Americans used herbal medicines less frequently than NHW to treat specific medical conditions (38 vs. 59%; p < 0.01), but were equally likely to report the use of herbal medicines as very important to maintain health and well-being (24 vs. 26%; p = 0.45). For both groups, almost half reported that herbal medicines used in combination with conventional medicine would be more helpful (49 vs. 48%; p = 0.81) and that they used herbal medicines because they thought that they were interesting to try (54 vs. 52%; p = 0.78).

Ethnic Variations of CAM Use Among AAs

Because use of herbal medicines and mind/body therapies was common among AA, we explored ethnic variations in use between Asian Indians (n = 182), Chinese (n = 191), and Filipinos (n = 155)—the three largest Asian groups surveyed. Herbal medicine use was higher among Chinese (32%) and Filipinos (26%) than Asian Indians (19%) during the previous 12 months (p < 0.01). A different pattern of use emerged for mind/body medicine. Asian Indians (31%) used mind/body medicine more often than Chinese (21%) or Filipinos (22%) (p < 0.01).

Independent Correlates of CAM Use Among AAs

Compared with AA males, females were more likely to use CAM [aPR = 1.24 (1.04, 1.46)]. Compared with AA who have less than a high school education, those who completed high school or its equivalency test [aPR = 1.40 (1.08, 1.81)] or had college education or higher [aPR = 1.40 (1.32, 1.49)] were more likely to use CAM. Compared with AA without chronic medical conditions, those with one condition [aPR = 1.26 (1.20, 1.32)] and at least two conditions [aPR = 1.29 (1.00, 1.65)] had higher CAM use.

DISCUSSION

Complementary and alternative medicine use is common among AA, and at least as common as use among NHW. Asian Americans use herbal medicines more often and bodywork therapies less often then NHW. Importantly, they were less likely than NHW to disclose their CAM use to conventional providers, particularly for herbal medicines and mind/body therapies.

Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies. Najm et al.6 studied a community-dwelling elderly population, and found that AA were higher users of acupuncture and Oriental medicine, while Hispanics were higher users of dietary supplements, home remedies, and curanderos (folk healers). Bair et al.7 reported common CAM use among Asian and white women, as well as ethnic differences in the use of specific CAM therapies. Nutritional remedies were common among white (41%) and Japanese (40%) women, and less common among Chinese (22%) and African Americans (24%). Using the 1995 Commonwealth Fund Survey, Mackenzie et al.8 found that CAM use was equally prevalent across ethnic populations (43%; n = 3452); however, the characteristics of CAM users varied for different CAM modalities. Asian Americans (n = 632) were nearly 13 times more likely to use acupuncture as compared to white Americans (n = 1114). In addition, AA were almost three times more likely to report herbal medicine use when compared with whites. Ultimately, these studies indicate that CAM use by specific ethnic groups may be predicted in part by the therapies with which they were familiar.

Despite the common use of CAM among AA, we found that only a minority had disclosed their CAM use to their conventional healthcare providers, especially herbal and mind/body therapies. These findings support those of Kuo et al.9 who found that AA had the highest rate of herbal medicine use (50%) and the lowest rate of disclosure to their physicians (31%). Importantly, high rates of herbal medicine use combined with low physician disclosure rates may lead to unknown herb–drug interactions. Our findings are particularly striking given that the overwhelming majority of AA respondents likely participated in English. Only small minorities had not completed high school or had been living in the United States for less than 5 years. We suspect that more vulnerable members of the AA community, including those with limited English proficiency or less education and recent immigrants, may be even less likely to discuss CAM use with their physicians. It is possible that these AA face significant barriers to health care and may use CAM therapies at even higher rates, possibly substituting CAM for medical conditions where there are highly effective conventional medical therapies.

Previous studies show that AA frequently encounter negative reactions from Western clinicians about their CAM use.10, 11 However, healthcare providers’ discussions of CAM therapy with their patients are associated with patients’ reports of improved quality of care.4 This emphasizes the need for physicians to provide culturally competent care by routinely asking patients about their use of CAM.

To our knowledge, this is the first national study to explore reasons for CAM use among Asians residing in the United States. We found that AA were more likely than NHW to use herbal medicine for health maintenance and less likely to use herbal medicine to treat a specific condition. Our findings for mind/body therapies were analogous to previous studies. In a multiracial Singapore community, a pilot study 12 found that 72% of those surveyed used CAM for the maintenance of health rather than the treatment of illness. These findings underscore the fact that discussions that focus just on treatment of illness may not be sufficient to elicit information about CAM. Discussions with patients should also emphasize health maintenance.

Among AA, we found significant ethnic variations in CAM use for the three largest groups surveyed. Nearly one-third of Asian Indians used at least one mind/body modality, whereas nearly one-third of Chinese used herbal medicines. Most previous studies of AA have examined them in aggregate, even though they represent a heterogeneous diaspora in which there exists no common language, tradition, or culture. Despite limited sample sizes, our findings suggest important ethnic variations in CAM use among Asian subgroups. Perhaps future survey tools will need to be culturally and linguistically competent to AA populations, given their projected dramatic growth.2

Among AA, we identified important characteristics that independently predicted CAM use: female gender, higher educational attainment, and the presence of chronic medical conditions. These findings are consistent with previously reported findings in the general population.13–15 It may not be surprising that the correlates of CAM use among AA in our study closely reflect those of their NHW counterparts because the vast majority were either born in America or had lived in the United States for more than 10 years.

Our study has several important limitations. First, NHIS does not over-sample AA; thus, the sample size of AA was relatively small, especially for analyses of Asian ethnic groups. Therefore, we had limited power to detect differences in CAM use between Asian and NHW Americans and variations across ethnic groups. Nevertheless, this is the largest national survey of CAM use among AA. Perhaps future NHIS instruments might over-sample Asian ethnic groups, thereby increasing statistical power to study important health care information about AA, including their CAM use. Second, NHIS does not describe many CAM modalities that are embedded in Asian traditions. This may unconsciously create an ethnocentric bias that underestimates the prevalence of CAM use among AA. For example, coining and cupping treatments are indigenous to some Asian cultures. However, the use of these, and several other traditional modalities, was not specifically elicited in NHIS; furthermore, there was no option to “write-in” responses. Many herbal remedies in NHIS are unique to the United States and are commonly marketed to middle-class NHW.3 Thus, NHIS cannot identify many CAM modalities specific to Asian cultures. This is further compounded by our suspicion that non- and limited-English-speaking AA were not captured in the sample. Even though NHIS is designed to be nationally representative, surveys are conducted in only English and Spanish. For non-English and non-Spanish speaking individuals to participate in the NIHS, they would have to rely upon English-speaking or Spanish-speaking household members to assist in translating questions during the interview.16 Finally, the term “Asian American” describes individuals from more than 25 ethnic groups originating from countries with distinct cultures, languages, and immigration patterns. The lack of attention to ethnic diversity among AA may lead to the oversimplification of assumptions regarding healthcare utilization 17 and physicians’ understanding of culturally competent care.18

Despite the limitations of the NHIS, our findings have important implications. Asian Americans do have high rates of CAM use. Our observation that AA have higher rates of herbal medicine use and low disclosure rates should raise concerns about potential herb–drug interactions. Asian Americans also have lower rates of bodywork use, which may represent underutilization of therapies effective for some chronic conditions, such as back pain. In conjunction with findings from previous studies, the successful delivery of healthcare must involve the education of physicians about culturally competent care. Given this, our study portends an even greater imperative for physicians to ask their patients about their use of CAM. The National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine and the National Library of Medicine provide valuable tools and updated information to educate healthcare providers about different CAM modalities http:www.nccam.nih.gov and http://www.medlineplus.gov. Eisenberg recommends that health care providers proactively discuss CAM use with their patients by conducting a formal discussion of patients’ preferences and expectations, utilizing symptom diaries, and ensuring follow-up visits in order to monitor for potentially harmful situations.19 Future research should seek to further understand CAM use and its relation to patient belief systems among ethnic minority populations.

References

Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004;343:1–19.

U.S. Census Bureau. U.S. Interim Projections by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2004.

Graham RE, Ahn AC, Davis RB, O’Connor BB, Eisenberg DM, Phillips RS. Use of complementary and alternative medical therapies among racial and ethnic minority adults: results from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(4):535–45.

Ahn AC, Ngo-Metzger Q, Legedza AT, Massagli MP, Clarridge BR, Phillips RS. Complementary and alternative medical therapy use among Chinese and Vietnamese Americans: prevalence, associated factors, and effects of patient–clinician communication. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(4):647–53.

Flanders WD, Rhodes PH. Large sample confidence intervals for regression standardized risks, risk ratios, and risk differences. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(7):697–704.

Najm W, Reinsch S, Hoehler F, Tobis J. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among the ethnic elderly. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9(3):50–7.

Bair YA, Gold EB, Greendale GA, et al. Ethnic differences in use of complementary and alternative medicine at midlife: longitudinal results from SWAN participants. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(11):1832–40.

Mackenzie ER, Taylor L, Bloom BS, Hufford DJ, Johnson JC. Ethnic minority use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM): a national probability survey of CAM utilizers. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9(4):50–6.

Kuo GM, Hawley ST, Weiss LT, Balkrishnan R, Volk RJ. Factors associated with herbal use among urban multiethnic primary care patients: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2004;4(1):18.

Sung CL. Asian patients’ distrust of western medical care: one perspective. Mt Sinai J Med. 1999;66(4):259–61.

Ngo-Metzger Q, Massagli MP, Clarridge BR, et al. Linguistic and cultural barriers to care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(1):44–52.

Lim MK, Sadarangani P, Chan HL, Heng JY. Complementary and alternative medicine use in multiracial Singapore. Complement Ther Med. 2005;13(1):16–24.

Conboy L, Patel S, Kaptchuk TJ, Gottlieb B, Eisenberg D, Acevedo-Garcia D. Sociodemographic determinants of the utilization of specific types of complementary and alternative medicine: an analysis based on a nationally representative survey sample. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11(6):977–94.

Astin JA. Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study. JAMA. 1998;279(19):1548–53.

Bausell RB, Lee WL, Berman BM. Demographic and health-related correlates to visits to complementary and alternative medical providers. Med Care. 2001;39(2):190–6.

Dey AN, Lucas JW. Physical and mental health characteristics of U.S.- and foreign-born adults: United States, 1998–2003. Adv Data. 2006;369:1–19.

Ryu H, Young WB, Kwak H. Differences in health insurance and health service utilization among Asian Americans: method for using the NHIS to identify unique patterns between ethnic groups. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2002;17:55–68.

Kakai H, Maskarinec G, Shumay DM, Tatsumura Y, Tasaki K. Ethnic differences in choices of health information by cancer patients using complementary and alternative medicine: an exploratory study with correspondence analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(4):851–62.

Eisenberg DM. Advising patients who seek alternative medical therapies. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(1):61–9.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by Grant R03-AT002236 from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, National Institutes of Health. Dr. Mehta is supported by an Institutional National Research Service Award (T32AT00051-06) from National Institutes of Health. Dr. Phillips is supported by a Mid-Career Investigator Award from the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, National Institutes of Health (K24-AT000589). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine or the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mehta, D.H., Phillips, R.S., Davis, R.B. et al. Use of Complementary and Alternative Therapies by Asian Americans. Results from the National Health Interview Survey. J GEN INTERN MED 22, 762–767 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0166-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0166-8