Abstract

Background

Solid pseudopapillary tumors (SPTs) are rare, benign tumors of the pancreas that present as heterogeneous masses. We sought to evaluate the short- and long-term outcomes of surgical resected SPTs. Patients managed via initial surveillance were compared to those who underwent upfront resection.

Methods

A prospectively maintained institutional database was used to identify patients who underwent surgical resection for a SPT between 1988 and 2018. Data on clinicopathological features and outcomes were collected and analyzed.

Results

Seventy-eight patients underwent surgical resection for SPT during the study period. The mean age was 34.0 ± 14.6 years and a majority were female (N = 67, 85.9%) and white (N = 46, 58.9%). Thirty patients (37.9%) were diagnosed incidentally. Imaging-based presumed diagnosis was SPT in 49 patients (62.8%). A majority were located in the body or tail of the pancreas (N = 47, 60.3%), and 48 patients (61.5%) underwent a distal pancreatectomy. The median tumor size was 4.0 cm (IQR, 3.0–6.0), nodal disease was present in three patients (3.9%), and R0 resection was performed in all patients. No difference was observed in clinicopathological features and outcomes between patients who were initially managed via surveillance and those who underwent upfront resection. None of the patients under surveillance had nodal disease or metastasis at the time of resection; however, one of them developed recurrence of disease 95.1 months after resection. At a median follow-up of 36.1 months (IQR, 8.1–62.1), 77 (%) patients were alive and one patient (1.3%) had a recurrence of disease at 95.1 months after resection and subsequently died due to disease.

Conclusions

SPTs are rare pancreatic tumors that are diagnosed most frequently in young females. While a majority are benign and have an indolent course, malignant behavior has been observed. Surgical resection can result in exceptional outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Solid pseudopapillary neoplasms (SPTs) are rare lesions of the pancreas that comprise 1 to 2% of all pancreatic tumors and were first described by Frantz in 1959.1,2 They are less frequently referred to as solid pseudopapillary neoplasms, Hamoudi tumors, Frantz tumors, solid and papillary tumors, papillary cystic tumors, or solid cystic tumors, though the definition was standardized as “solid pseudopapillary tumors” by the World Health Organization in 1996.3,4

SPTs are frequently diagnosed in young females as large heterogeneous (mixed solid and cystic features) pancreatic masses.5 They typically present with vague non-specific symptoms including epigastric pain, dyspepsia, early satiety, and nausea and vomiting.6 Radiographic evaluation demonstrates cystic features, often accompanied with calcifications.7,8 On histopathological examination, SPTs are found to be surrounded by blood vessels, contain cystic degeneration, and intracystic hemorrhage.6,8 They have an indolent course, though malignant behavior has been observed in around 10% of documented cases.1,5,9,10 Complete extirpation of both local disease and any metastatic disease is associated with favorable outcomes and long-term survival.6,8,11

Given that SPTs are exceedingly rare, literature available on them is limited to case series, including our institutional series of 2, 7, and 37 cases.6,12,13 Herein, we sought to report the largest single institution experience of resected SPTs over a 30-year period. Furthermore, we compared clinicopathological characteristics and outcomes of patients who were managed via upfront resection with those who were initially managed via surveillance followed by resection.

Methods

A prospectively maintained institutional database was used to identify patients who underwent surgical resection for SPT between 1988 and 2018. Data on clinicopathological details and outcomes were extracted from the aforementioned database, and missing data were collected retrospectively from the patients’ electronic medical records. Our institutional definition of SPT incorporates the following criteria: “an epithelial neoplasm composed of discohesive polygonal cells that surround delicate blood vessels and form solid masses, with frequent cystic degeneration and intracystic hemorrhage. These neoplastic cells have to have uniform nuclei, finely stippled chromatin, and usually nuclear grooves. Abnormal nuclear labeling with antibodies to β-catenin [is] considered to be strongly supportive of the diagnosis of SPT”.3,6 Postoperative complications were defined as any complication occurring within 90 days of the operation. Complications were graded according to the Clavien-Dindo Classification index.14 Postoperative pancreatic insufficiency was defined as the need for chronic pancreatic enzyme supplementation. A surveillance-first approach was defined as routine surveillance of at least 6 months following diagnosis and prior to surgical resection.

A Student’s t test or Mann-Whitney U test was utilized for continuous variables as deemed appropriate while the Pearson’s chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test was utilized for categorical variables. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages while continuous variables were reported as means and standard deviation or median and interquartile range as deemed necessary. Overall survival was calculated from the time of surgery. A P value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 3.3.3 (Vienna, Austria).

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Research and complied with all Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations.

Results

During the study period, 78 patients underwent surgical resection for a SPT at our institution. A majority were female (N = 67, 85.9%) and white (N = 46, 58.9%). The mean age at resection was 34.0 ± 14.6 years. A majority of patients were symptomatic at presentation (N = 54, 69.2%), with the most common symptom being epigastric discomfort (N = 33, 42.3%) followed by nausea and vomiting (N = 11, 14.1%). Baseline characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

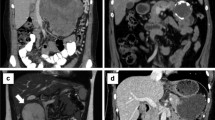

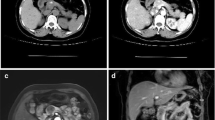

After an initial evaluation via cross-sectional imaging and diagnostic biopsy, the presumed diagnosis was SPT in 57 patients (73.1%). Radiologically, in 50 patients (64.1%), tumors had heterogeneous (solid and cystic) features (Fig. 1a). The radiological preoperative diagnosis was SPT in 49 patients (62.8%), cystic neoplasm in 24 patients (30.8%), and neuroendocrine tumor in 5 patients (6.4%). Calcification was observed in 13 patients (16.7%) (Fig. 1b). Endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration (EUS/FNA) was performed in 44 patients (56.4%). The results of these biopsies were suggestive of SPT in 35 patients (79.5%), and neuroendocrine tumor and chronic pancreatitis in 2 patients (4.5%) each respectively. Preoperative cancer antigen 19–9 (CA19–9) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) values were within normal limits in all patients. Tumors were most commonly located in the body or tail of the pancreas (N = 51, 65.4%) followed by the pancreatic head (N = 27, 34.6%). Pancreatic duct dilatation was observed in six patients (7.7%). Furthermore, macrovascular involvement was observed in 26 patients (33.3%). The portal vein and superior mesenteric venous (PV/SMV) were the most commonly involved vessels (N = 12, 46.2%), followed by the splenic vein (N = 11, 42.3%). No patients had metastatic disease at presentation (Figs. 2 and 3). Data on clinical workup of these patients are detailed in Table 2.

CT scan of a 19-year-old patient who presented with acute abdominal pain. CT demonstrated a large, heterogeneous, well-circumscribed mass originating from the pancreatic head and neck with minimal enhancement as seen on the axial (a) and coronal (b) planes. Abutment of the portal vein and superior mesenteric vein was observed without any invasion of other vessels. The patient was recommended surgical resection

CT scan of a 31-year-old female who presented with abdominal pain. CT demonstrated a large heterogeneous mass with rim calcification in the body and tail of the pancreas (a). Given the extent of vascular involvement and the increasing size of the lesion on follow up imaging the patient was recommended chemotherapy. The tumor remained stable on therapy (b) and surgical resection was recommended

Of note, one patient was explored at an outside hospital for attempted curative resection but was aborted due to the extensive vascular involvement of the porto-splenic confluence. Upon review at our multidisciplinary clinic, a recommendation of neoadjuvant chemotherapy with a combination of a WNT/β-catenin inhibitor and FOLFIRINOX was made given the extent of vascular involvement. After 6 months of therapy, the patient underwent surgical resection.

The most common type of surgery was a distal pancreatectomy (N = 48, 61.5%), followed by pancreaticoduodenectomy (N = 27, 34.6%), total pancreatectomy (N = 2, 2.6%), and a central pancreatectomy (N = 1, 1.3%) (Table 3). Vascular resection was performed in five patients (6.4%), all requiring a primary repair of the PV/SMV confluence. The median length of surgery was 340 min (IQR 235–406), and the median estimated blood loss was 300 mL (IQR, 150–500).

The median tumor size was 4.0 cm (IQR, 3.0–6.0). Eight patients (10.3%) had perineural invasion, while four (5.1%) had lymphovascular invasion, and three patients (3.9%) were found to have nodal disease. A negative margin was obtained in all patients.

Data on postoperative complications are listed in Table 3. In total, 29 (37.2%) patients experienced clinically relevant postoperative complications. The most common complication was a postoperative pancreatic fistula (N = 15, 19.2%) followed by delayed gastric emptying (N = 8, 10.3%). The median length of hospitalization was 8 days (IQR, 5–11). Eight patients (10.3%) required 90-day readmission, and there were no 90-day mortalities.

The median length of follow-up was 36 months (IQR, 8–62). During this period, seven patients (8.9%) had new onset of diabetes mellitus and six patients (7.7%) developed pancreatic insufficiency. One patient (1.3%) developed a liver recurrence at 95.1 months after resection. This was evaluated via ultrasound-guided biopsy which revealed SPT with positive β-catenin staining. This patient was subsequently treated with gemcitabine, and the post recurrence survival was 37.7 months (132.8 months after resection). At the time of the last follow-up, 77 patients (98.7%) were alive and free of disease.

Five patients (6.4%) were initially managed via surveillance. All five (100.0%) presented incidentally and respective attending physicians and patients collectively agreed on a surveillance-first approach. The median time between diagnosis and resection was 12 months (IQR, 8 to 39). When compared to patients managed via an upfront surgery, no difference was observed in clinicopathological characteristics between the two groups. (Table 4).

Discussion

First documented in 1959 by Frantz, SPTs are rare tumors of the pancreas.2 Both literature and the current series suggest that these tumors have a strong preference for younger females.15 Reddy et al. reported that the rate of diagnosis of SPT is on the rise.6 Indeed, two-thirds of their series were diagnosed in the last one-third of the study period. This notion holds true in the present study, which added 41 cases in the subsequent 10-year period. This is, perhaps in large part, due to improvements in diagnostic modalities and an increased utilization of cross-sectional imaging and endoscopic biopsies. Of note, the incorporation of EUS/FNA significantly increases the diagnostic yield of pancreatic cysts over CT alone.16,17 A systemic review by Law et al., in 2012, identified 484 studies in English literature reporting a total of 2744 SPTs.15 Interestingly, in their study spanning five decades (1961–2012), 87.8% were diagnosed between 2000 and 2012.

In the aforementioned meta-analysis, 87.8% of cases were young females. Similarly, a recent systemic review by Bender et al. identified 135 studies reporting 523 SPTs in pediatric patients.18 Among this pediatric cohort, 83% of patients were female. Similar trends were observed in the current series; however, SPTs were also observed in males and older females. Various studies have reported that males who present with SPTs have a tendency to present at an older age as compared to their female counterparts.10,19

Similar to other studies, a significant number of patients in this study (38.4%) were diagnosed incidentally.15,20 When symptomatic patients typically present with vague and non-specific symptoms including abdominal discomfort, nausea, and vomiting, resulting in a delay in diagnosis.6,15 Interestingly, in this study, while 34.6% of tumors were located in the head of the pancreas, only one patient (1.3%) presented with jaundice. The differential diagnosis of SPT includes mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCN), serous cystic neoplasms (SCN), and cystic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. When considering older patients, the possibility of a solid invasive cancer developing in the setting of a cystic neoplasm must be considered.6 SPTs are frequently diagnosed accurately using cross-sectional imaging, though definitive diagnosis relies on immunohistochemical analysis.21 However, a cytological diagnosis will likely not change the management of these tumors.

SPTs are genetically distinct from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). Whereas KRAS mutations are a hallmark of PDAC, this oncogene is rarely, if ever, mutated in SPTs.22,23 In contrast, one of the earliest studies investigating the molecular mechanisms of development of SPT identified alterations to the tumor suppressor gene, adenomatosis polyposis coli (APC), and β-catenin protein.23 Notably, APC/β-catenin mutations are not considered to be implicated in ductal neoplastic development. Downstream, the cell-cycle regulator cyclin D1 has been reported to be overexpressed in 10 to 70% of SPTs.23,24 In line with β-catenin mutations, another study identified WNT signaling as a key driver in the tumorigenesis of SPTs.24 Recently, a bioinformatics analysis of SPTs provided unprecedented access to the genetic drivers of the development of SPT and identified mutations in the EGFR, FYN, JUN, GCG, MYC, and CD44 genes. Additionally, the ErbB and GnRH signaling pathways were identified as possible drivers of progression in SPTs.25 Interestingly, in a study of five metastatic SPTs, Amato et al. found that KDM6A and BAP1 expression were significantly reduced in metastatic SPTs.26 These findings suggest that KDM6A and BAP1 may function as a barrier to SPT progression and/or metastasis.26

A number of studies have discussed the immunohistochemistry findings of SPTs. Recently, Lanke et al. summarized these findings.21 Commonly, SPTs stain positive for β-catenin (both nuclear and cytoplasmic), vimentin, synaptophysin, progesterone receptor, CD56, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), CD10, and E-cadherin (loss of both membrane and nuclear).21,27 Kim et al. also identified the androgen receptor (AR), lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF-1), and transcription factor for immunoglobulin heavy-chain enhancer 3 (TFE3) as putative diagnostic markers of SPTs.28

Though SPTs are generally benign, those with malignant potential have been reported.1,5,9 Similarly, in this series, four patients displayed metastatic behavior; three had positive nodal disease at the time of resection and one developed liver recurrence after surgery. Of note, the three patients with nodal disease were free of disease at 2.1, 82.7, and 136.1 months after resection. Interestingly in addition to nodal disease, margin positivity was not found to be a predictor of poorer outcomes.29,30 Furthermore, in literature, patients who presented with metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis achieved excellent long-term outcomes after resection of their disease.6,8,11,31 Based on these data, it is clear that surgical resection of disease even in the presence of distant disease is recommended.20,32

Based on current literature, the role of chemotherapy and radiotherapy for SPTs is unclear. In a meta-analysis, Law et al. reported 47 patients (6.3%) who received adjuvant chemotherapy using either Fluorouracil (5FU)-based and Gemcitabine-based regimens.15 Follow-up was available for 24 of these patients. Six (25.0%) died from their disease while the remaining patients were alive with a mean follow up of 51.1 ± 56.2 months after diagnosis. One interesting case was reported by Tajima et al., where the patient presented with liver metastasis who underwent resection of the primary tumor followed by adjuvant gemcitabine and an oral fluoropryrimidine derivative.31 This patient progressed on this regimen and was switched to hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy of gemcitabine with good disease response. Transarterial tumor embolization (TAE) and metastasectomy were performed successfully.31 At the time of last follow up, the patient was under monthly observation and was receiving maintenance chemotherapy. In another case report, a patient was diagnosed with locally advanced disease due to extensive portal vein invasion and was treated solely with radiotherapy achieving a complete radiographic response.33 This case highlights that SPTs may be radiosensitive and begs the question of whether or not radiation therapy could serve as an effective treatment for smaller SPTs. Lastly, another case report presented a patient with a large 13 cm SPT that was managed successfully with gemcitabine-based chemotherapy.34 This patient was diagnosed with a locally advanced tumor with local invasion of the mesocolon, porta hepatis, and gastrocolic ligament. The patient was initially treated with 5-FU-based chemotherapy and standard radiation (50*4 Gy) though no tumor response was appreciated. The patient was switched to gemcitabine-based chemotherapy and experienced a 69.2% reduction in tumor size followed by successful surgical resection. The patient was alive without recurrence at 36 month follow-up. In our series, one patient received chemotherapy due to vascular involvement and subsequently underwent successful resection.

Favorable outcomes and long-term survival have been reported for nearly all patients undergoing resection for SPTs. In fact, the rate of 5-year survival approaches 100% in most studies even in the presence of metastatic or recurrent disease.15,32,35,36,37 While data are limited, it can be suggested that young asymptomatic patients with an incidental diagnosis of SPTs can be managed initially via surveillance. Patients with benign SPTs are still at risk for disease recurrence; therefore, it is important to maintain long-term follow-up.15,36 Data available on predictors of metastatic spread or recurrence of disease are heterogeneous. Some reports have identified tumor size > 5.0 cm, the presence of lymphovascular and perineural invasion, and nuclear grade as predictive factors.6,36,38 Kang et al. reported a rate of recurrence of 2.6%; large tumor size, microscopic malignant features, and metastatic disease at presentation were independently predictive of recurrence.37 Common biomarkers including CA19–9 and CEA have not shown to be of diagnostic value for SPTs. Rastogi et al. recently reported that increased enhancement during the delayed phase of a contrast-enhanced computed tomography is suggestive of aggressive tumor biology.39

In conclusion, SPTs are rare tumors of the pancreas that are identified most frequently in young females. While a majority are benign, malignant behavior has been observed. In younger asymptomatic patients with incidental tumors, initial surveillance may be feasible but needs further study. Surgical resection of SPTs, even in the presence of metastatic disease, can result in exceptional outcomes.

References

Martin RC, Klimstra DS, Brennan MF, Conlon KC. Solid-pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas: a surgical enigma? Ann Surg Oncol 2002; 9: 35–40.

Frantz V. Tumors of the Pancreas. Atlas of Tumor Pathology 1959; 2.

Hruban RH. Solid Pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas. 2007.

Kloppel. Histological typing of tumors of the exocrine pancreas. 1996.

Kawamoto S, Scudiere J, Hruban RH et al. Solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: spectrum of findings on multidetector CT. Clin Imaging 2011; 35: 21–28.

Reddy S, Cameron JL, Scudiere J et al. Surgical management of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas (Franz or Hamoudi tumors): a large single-institutional series. J Am Coll Surg 2009; 208: 950–957; discussion 957-959.

Zheng X, Tan X, Wu B. [CT imaging features and their correlation with pathological findings of solid pseudopapillary tumor of pancreas]. Sheng Wu Yi Xue Gong Cheng Xue Za Zhi 2014; 31: 107–112.

Guo N, Zhou QB, Chen RF et al. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: analysis of 24 cases. Can J Surg 2011; 54: 368–374.

Ng KH, Tan PH, Thng CH, Ooi LL. Solid pseudopapillary tumour of the pancreas. ANZ J Surg 2003; 73: 410–415.

Machado MC, Machado MA, Bacchella T et al. Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: distinct patterns of onset, diagnosis, and prognosis for male versus female patients. Surgery 2008; 143: 29–34.

Mao C, Guvendi M, Domenico DR et al. Papillary cystic and solid tumors of the pancreas: a pancreatic embryonic tumor? Studies of three cases and cumulative review of the world’s literature. Surgery 1995; 118: 821–828.

Sanfey H, Mendelsohn G, Cameron JL. Solid and papillary neoplasm of the pancreas. A potentially curable surgical lesion. Ann Surg 1983; 197: 272–275.

Zinner MJ, Shurbaji MS, Cameron JL. Solid and papillary epithelial neoplasms of the pancreas. Surgery 1990; 108: 475–480.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004; 240: 205–213.

Law JK, Ahmed A, Singh VK et al. A systematic review of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasms: are these rare lesions? Pancreas 2014; 43: 331–337.

Khashab MA, Kim K, Lennon AM et al. Should we do EUS/FNA on patients with pancreatic cysts? The incremental diagnostic yield of EUS over CT/MRI for prediction of cystic neoplasms. Pancreas 2013; 42: 717–721.

Law JK, Stoita A, Wever W et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration improves the pre-operative diagnostic yield of solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: an international multicenter case series (with video). Surg Endosc 2014; 28: 2592–2598.

Bender AM, Thompson ED, Hackam DJ et al. Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasm of the Pancreas in a Young Pediatric Patient: A Case Report and Systematic Review of the Literature. Pancreas 2018; 47: 1364–1368.

Cai YQ, Xie SM, Ran X et al. Solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas in male patients: report of 16 cases. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 6939–6945.

Lee SE, Jang JY, Hwang DW et al. Clinical features and outcome of solid pseudopapillary neoplasm: differences between adults and children. Arch Surg 2008; 143: 1218–1221.

Lanke G, Ali FS, Lee JH. Clinical update on the management of pseudopapillary tumor of pancreas. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2018; 10: 145–155.

Wolfgang CL, Herman JM, Laheru DA et al. Recent progress in pancreatic cancer. CA Cancer J Clin 2013; 63: 318–348.

Abraham SC, Klimstra DS, Wilentz RE et al. Solid-pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas are genetically distinct from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas and almost always harbor beta-catenin mutations. Am J Pathol 2002; 160: 1361–1369.

Tanaka Y, Kato K, Notohara K et al. Frequent beta-catenin mutation and cytoplasmic/nuclear accumulation in pancreatic solid-pseudopapillary neoplasm. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 8401–8404.

Zhang Y, Han X, Wu H, Zhou Y. Bioinformatics analysis of transcription profiling of solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. Mol Med Rep 2017; 16: 1635–1642.

Amato E, Mafficini A, Hirabayashi K et al. Molecular alterations associated with metastases of solid pseudopapillary neoplasms of the pancreas. J Pathol 2018.

Serra S, Chetty R. Revision 2: an immunohistochemical approach and evaluation of solid pseudopapillary tumour of the pancreas. J Clin Pathol 2008; 61: 1153–1159.

Kim EK, Jang M, Park M, Kim H. LEF1, TFE3, and AR are putative diagnostic markers of solid pseudopapillary neoplasms. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 93404–93413.

Jutric Z, Rozenfeld Y, Grendar J et al. Analysis of 340 Patients with Solid Pseudopapillary Tumors of the Pancreas: A Closer Look at Patients with Metastatic Disease. Ann Surg Oncol 2017; 24: 2015–2022.

Serrano PE, Serra S, Al-Ali H et al. Risk factors associated with recurrence in patients with solid pseudopapillary tumors of the pancreas. JOP 2014; 15: 561–568.

Tajima H, Takamura H, Kitagawa H et al. Multiple liver metastases of pancreatic solid pseudopapillary tumor treated with resection following chemotherapy and transcatheter arterial embolization: A case report. Oncol Lett 2015; 9: 1733–1738.

El Nakeeb A, Abdel Wahab M, Elkashef WF et al. Solid pseudopapillary tumour of the pancreas: Incidence, prognosis and outcome of surgery (single center experience). Int J Surg 2013; 11: 447–457.

Fried P, Cooper J, Balthazar E et al. A role for radiotherapy in the treatment of solid and papillary neoplasms of the pancreas. Cancer 1985; 56: 2783–2785.

Maffuz A, Bustamante Fde T, Silva JA, Torres-Vargas S. Preoperative gemcitabine for unresectable, solid pseudopapillary tumour of the pancreas. Lancet Oncol 2005; 6: 185–186.

D'Haese JG, Werner J. Surgery of Cystic Tumors of the Pancreas - Why, When, and How? Visc Med 2018; 34: 206–210.

You L, Yang F, Fu DL. Prediction of malignancy and adverse outcome of solid pseudopapillary tumor of the pancreas. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2018; 10: 184–193.

Kang CM, Choi SH, Kim SC et al. Predicting recurrence of pancreatic solid pseudopapillary tumors after surgical resection: a multicenter analysis in Korea. Ann Surg 2014; 260: 348–355.

Nishihara K, Nagoshi M, Tsuneyoshi M et al. Papillary cystic tumors of the pancreas. Assessment of their malignant potential. Cancer 1993; 71: 82–92.

Rastogi A, Assing M, Taggart M et al. Does Computed Tomography Have the Ability to Differentiate Aggressive From Nonaggressive Solid Pseudopapillary Neoplasm? J Comput Assist Tomogr 2018; 42: 405–411.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed to the conception of the study. AAJ, MJWr, TS, and YZ preformed data collection and composed the first draft of the manuscript. RAB, JU, JH, JLC, MAM, CLW, and MJWe critically reviewed and edited the final draft of the manuscript. All the authors take responsibility for the accuracy of the repotted data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Research and complied with all Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act regulations.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wright, M.J., Javed, A.A., Saunders, T. et al. Surgical Resection of 78 Pancreatic Solid Pseudopapillary Tumors: a 30-Year Single Institutional Experience. J Gastrointest Surg 24, 874–881 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-019-04252-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-019-04252-7