Abstract

Background

Participation by surgical trainees in complex procedures is key to their development as future practicing surgeons. The impact of surgical fellows versus general surgery resident assistance on outcomes in pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) has not been well studied. The purpose of this study was to determine differences in patient outcomes based on level of surgical trainee.

Methods

Consecutive cases of PD (n = 254) were reviewed at a single high-volume institution over a 2-year period (July 2013–June 2015). Thirty-day outcomes were monitored through the American College of Surgeon’s National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) and Quality In-Training Initiative. Patient outcomes were compared between PD assisted by general surgery residents versus hepatopancreatobiliary fellows.

Results

The hepatopancreatobiliary surgery fellows and general surgery residents participated in 109 and 145 PDs, respectively. The incidence of each individual postoperative complication (renal, infectious, pancreatectomy-specific, and cardiopulmonary), total morbidity, mortality, and failure to rescue were the same between groups.

Conclusions

Patient operative outcomes were the same between fellow- and resident-assisted PD. These results suggest that hepatopancreatobiliary surgery fellows and general surgery residents should be offered the same opportunities to participate in complex general surgery procedures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The delicate balance of patient safety with maximal trainee participation in operative cases is central to general surgery education. Despite emerging technology in surgical simulation,1 hands-on surgical training remains critical for development of operative technique. However, many patients express concern for resident involvement and even refuse resident participation in their care.2 Public perception of potential risks associated with resident-performed surgery is increasing with media portrayals. Thus, demand for only the highest quality of care leads to exclusion of surgical trainees. Although public perception of increased risk is supported by multiple published studies,3,4,5,6,7, – 8 a thorough review of the literature uncovers heterogeneous data. Many studies have shown either no effect,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17, – 18 or in some cases, improvement of operative outcomes with surgical trainee participation.19,20,21,22, – 23

Patient outcomes are becoming increasingly important as the US healthcare system shifts from reimbursement plans based on services received to quality achieved.24 Identification of factors that impact patient outcomes is crucial in order to best control these outcomes. As previously stated, one controversial factor is surgical trainee participation. Less well studied is the experience level of surgical trainee effect on outcomes. Despite varying answers to the effect of trainee level, multiple authors have found improved outcomes with increasing surgical experience.14 , 25 , 26 Does the correlation of improved outcomes with increased experience carry over to surgical fellowship? Do surgical fellows have better operative outcomes than residents? As general surgeons become increasingly specialized, surgical fellowships are likewise expanding.27 This changing landscape of general surgery necessitates a close examination of surgical curriculum. While all general surgeons should be proficient in basic general surgery procedures such as laparoscopic appendectomy, inguinal hernia repair, and laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the need for exposure to more complex procedures is less clear. Due to reports of worse outcomes,6 , 25 some have questioned the practicality of resident participation in complex operations. These cases may be better suited for surgical fellows. Not only is fellow assistance possibly related to improved outcomes but also surgical fellows will ultimately need proficiency in these complex surgical cases while residents may not. Data directly comparing operative outcomes from fellow-assisted versus resident-assisted cases are heterogeneous and scarce.3 , 12 , 14 , 15 We therefore sought to compare patient outcomes following a complex general surgery procedure, pancreatoduodenectomy (PD), assisted by hepatopancreatobiliary (HPB) surgery fellows versus general surgery residents.

Methods

Study Population

The American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) database was used to identify all PD cases at Indiana University Health University Hospital over a 2-year period (July 2013 to June 2015). NSQIP variables were augmented by data from our institutional pancreatectomy database (such as pancreatic duct size, gland texture, and vein resection). All cases were performed by an attending surgeon and assisted by a surgical trainee (HPB fellow versus general surgery resident); no cases were excluded. Each attending surgeon performing PD was beyond the learning curve of 60 cases. PD was performed by one of five HPB surgeons at Indiana University Health University Hospital spanning two general surgery services staffed by one HPB fellow, one chief resident (PGY5), and two fourth year residents (PGY4) to assist the five HPB surgeons. Cases were assigned by the most senior surgical trainee on each general surgery service. Postoperative care was also primarily managed by the most senior trainee on the service. Trainees examined patients and reviewed electronic medical records for patient data several times daily and subsequently plans were discussed with attending surgeons who oversaw and directed postoperative care.

Study Design

Thirty-day outcomes of all patients undergoing PD were monitored and tracked through ACS-NSQIP. Quality In-Training Initiative (QITI) is a novel component of NSQIP which allows for documentation of PGY level of the trainee assisting in the case.28 Mortality, individual morbidities, total morbidities, readmission, hospital length of stay, and failure to rescue were compared between groups based on level of surgical trainee. Specific morbidities tabulated included the following:

-

1.

Infectious complications: surgical site infections (superficial, deep, and organ space infections), urinary tract infections, pneumonia, sepsis, and septic shock

-

2.

Renal complications: acute renal failure and renal insufficiency

-

3.

Pancreatectomy-specific complications: delayed gastric emptying and pancreatic fistula

-

4.

Cardiopulmonary complications: pulmonary embolism, mechanical ventilator support for greater than 48 h, unplanned intubation, myocardial infarction, and cardiac arrest

Failure to rescue (FTR) was calculated using total patients with at least one morbidity as denominator and mortality within those patients as numerator.

Comparisons between operations done with surgical trainees of varying levels included assessment of preoperative/intraoperative variables and operative outcomes previously described. All statistical analyses used IBM SPSS, version 24. Descriptive statistics, including frequency, mean, and standard deviation were calculated when appropriate. Continuous data was analyzed with Student’s t test and ANOVA; categorical data was analyzed with chi-square. p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Two hundred fifty-four patients underwent PD at Indiana University Health University Hospital from July 2013 to June 2015. HPB fellows assisted with 109 operations and general surgery residents assisted with 145 operations. Table 1 displays patient demographic data. There were no differences in patient gender or age between fellow and resident groups. Additionally, patient comorbid conditions were the same in both fellow and resident groups (Table 1). Surrogate markers of operative difficulty level including pancreatic duct size, gland texture, vein reconstruction, and operative time were also the same in patients whose operations were assisted by both fellows and residents (Table 2). Table 2 also shows no difference in surgical pathology in fellow-assisted versus resident-assisted cases (malignant 64/66%; pancreatitis 17/16%).

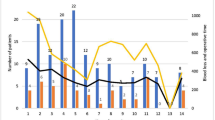

Table 3 displays incidence of each postoperative outcome. Mean length of stay for patients operated on by fellows and residents was 7 days. Renal, infectious, cardiac, pulmonary and pancreatectomy-specific postoperative occurrences were the same in both fellow-assisted and resident-assisted cases. FTR, or the rate of mortality within those experiencing morbidity, was 6 and 4% in fellow-assisted and resident-assisted operations. Eighty and 139 total morbidities resulted from operations assisted by fellows and residents, respectively; the mean number of morbidities per patient was 0.7 and 1.0 (p = 0.21). Forty-three (39%) and 71 (49%) patients experienced at least one morbidity in the fellow and resident groups (p = 0.16) (Fig. 1). There were also no differences in incidence of return to the operating room (3 versus 5%; p = 0.52), readmission (17 versus 18%; p = 0.61), or mortality (2 versus 3%; p = 1.0) among fellows and residents, respectively. Attending specific postoperative outcomes were also stratified by resident versus fellow which showed no differences (data not shown).

Postoperative outcomes. Pancreatoduodenectomy outcomes are compared between fellow- and resident-assisted cases. Frequencies of each postoperative outcome are displayed here. Morbidity includes all patients with at least one morbidity. The included morbidities are the following: ARF, PNA, SSI, UTI, PE, cardiac arrest, MI, sepsis, unplanned intubation, vent >48 h, RTOR, DGE, PF. RTOR return to operating room

Pancreatic fistulas were graded based on International Study Group Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) definition.29 Eighteen (16.5%) pancreatic fistulas occurred within the fellow-assisted group and 35 (24.1%) within the resident-assisted group (Table 4). Grade B + C (clinically relevant) fistulas occurred in 5.5 and 9.7% of cases. There were no significant differences in pancreatic fistula grades (either total or B/C) among fellow- and resident-assisted operations (p = 0.96).

Surgical residents were further stratified based on their level of training. Seventy chief residents (post-graduate year “PGY” 5) and 75 junior residents (PGY 1–4) were compared to HPB fellows (Table 5). All previously described outcomes, including all specific morbidities, total morbidity, and mortality, were again compared between subgroups. Incidence of total pancreatic fistula resulted from significantly more operations assisted by chief residents (31%) than junior residents (19%) and fellows (16%, p = 0.034). When considering only clinically relevant fistulas (grade B/C), no difference in fistula rate was observed between groups (chief 8.6%, junior 10.7%, and fellow 5.5%; p = 0.43) Total morbidity, mortality, and all other specific morbidities were the same between subgroups. Likewise, HPB fellows were stratified based on experience. There were no differences in fellow outcomes based on which quarter of the academic year the operation was performed.

Discussion

In this study, we report 254 consecutive PD with surgical trainee participation over a 2-year period. We found no difference in preoperative or intraoperative factors between PD assisted by fellows versus residents. Additionally, we found no difference in any specific postoperative occurrence (infectious, renal, cardiopulmonary, or pancreatectomy-specific), total morbidity, mortality, FTR, or operative time. When stratified by level of surgical trainee, chief residents (PGY-5) had higher rates of pancreatic fistula (31%) than fellows (16%) and junior residents (PGY ≤4; 19%; p = 0.034). However, total morbidity and all other specific postoperative morbidities were the same between subgroups.

Although we found a correlation between chief resident assistance and an increased pancreatic fistula rate, the interpretation of this is not clearly evident by a statistically lower rate in the junior resident group. Of note, after exclusion of non-clinically relevant fistulas (grade A), no difference in fistula rate was observed. Several other studies have demonstrated increased operative time and morbidity in cases assisted by more senior residents.7 , 8 , 30 , 31 Increased chief resident autonomy in the operating room may explain the higher incidence of pancreatic fistula. Typically, attending surgeons more freely allow chief residents to perform the most critical steps of procedures including pancreatic anastomoses. Although this latter notion is widely accepted, there is no data to support it. As has been discussed in multiple studies, we were unable to reliably measure the degree of surgical trainee participation in operative cases and therefore had no way to study its effect on patient outcomes.18 , 22 , 32 Based on attending surgeon survey, PGY2-3 residents did not perform pancreaticojejunal anastomoses, while PGY4 and PGY5 (chief) residents performed the majority (approximately 90%) and HPB fellows performed all pancreatojejunal anastomoses. Multiple authors have identified case volume of surgeons performing PD as a risk factor for PF development. Completion of less than 50 PD was independently associated with higher risk of PF (10 versus 20%) within previous published data.33 Chief residents acting as primary surgeon certainly possess this risk factor, having usually performed very few PD operations. A recent study by Hogg et al. established a technical scoring system for surgeon performance in robotic pancreatectomy that independently predicts PF; better technical performance led to decreased probability of PF.34 This data again supports the idea that less-skilled chief resident surgeons operating as primary surgeons may have higher incidence of postoperative PF.

These data suggest that there is no additional patient safety benefit associated with HPB fellow participation over surgical resident participation in PD. Multiple previous studies support these results including two that compare outcomes following minimally invasive operations assisted by fellow versus resident.3 , 35 Linn et al. analyzed patient outcomes before and after a minimally invasive fellowship was terminated and found that although operative time had increased with resident participation, postoperative complications had remained the same.35 Likewise, Davis et al. reported no difference in outcomes of minimally invasive operations assisted by fellows versus residents.3 Similar studies showed equivalence in patient outcomes following fellow- and resident-assisted laparoscopic ventral hernia repair15 and pediatric laparoscopic appendectomy.12 In contrast to our data, both studies found increased operative time in the fellow groups. An additional supporting article found no difference in fellow versus resident outcomes in PD.14 This same study compared individual resident complication rates over time. As the resident gained experience performing more PDs, their complication rates decreased. Authors were able to predict PD-specific complication rate based on resident case number. However, the decrease in complication rate was only observed for up to 15 cases, and each additional PD offered no further decrease. Based on existing literature and the results presented here, both fellows and residents should continue to be allowed involvement in complex general surgical procedures.

Our conclusions are limited by several factors. Although 254 PD outcomes were analyzed, this data is from only 2 years at a single institution. From this dataset, we were unable to evaluate the degree of trainee participation during PD, as described in previous studies discussed above. The heterogeneity of trainee participation is broad, thus creating comparison groups on PGY level may not be completely reflective of ability or experience. Intraoperative differences can also arise that make one PD more difficult than another including vascular resection or presence of active pancreatitis; these types of factors are not as clearly defined in a retrospective series. Another limitation included the inability to control for postoperative management in a retrospective series; heterogeneity of postoperative management is created by both the attending surgeon compared against other surgeons and surgical trainee compared against other trainees guiding care and leads to inherent discrepancy in management. Enhanced recovery after surgery protocols for pancreatectomy could control for many aspects of postoperative management going forward. A prospective, multi-institutional study is needed to eliminate bias introduced by limited data. We intend to query other high-volume institutions who train both fellows and residents in regards to performing a multi-institutional prospective study in which patients could be randomized to fellow versus resident participation. This would require an evaluation of degree of resident participation immediately postoperative graded by the attending surgeon as well as an assessment of degree of difficulty of the case. This type of study would answer questions formulated based on preliminary data presented here.

Conclusion

This retrospective, single-institution study examined 254 consecutive PDs over 2 0years. From these data, we conclude patient operative outcomes are the same between fellow- and resident-assisted PD. Although there was an increased rate of PF among chief residents when groups were subdivided by level of trainee, this may be due to the confounding degree of trainee participation. These results suggest that in the training environment, HPB surgery fellows and general surgical residents are equivocal in terms of postoperative outcomes following PD. Therefore, fellows and residents should be offered the same opportunities to participate in complex general surgery procedures.

References

Beyer L, Troyer JD, Mancini J, Bladou F, Berdah SV, Karsenty G, Impact of laparoscopy simulator training on the technical skills of future surgeons in the operating room: a prospective study. Am. J. Surg. 2011, 202 (3), 265–72.

Dutta S, Dunnington G, Blanchard MC, Spielman B, DaRosa D, Joehl RJ, “And doctor, no residents please!”. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2003, 197 (6), 1012–7.

Davis SS, Jr., Husain FA, Lin E, Nandipati KC, Perez S, Sweeney JF, Resident participation in index laparoscopic general surgical cases: impact of the learning environment on surgical outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2013, 216 (1), 96–104.

Advani V, Ahad S, Gonczy C, Markwell S, Hassan I, Does resident involvement affect surgical times and complication rates during laparoscopic appendectomy for uncomplicated appendicitis? An analysis of 16,849 cases from the ACS-NSQIP. Am. J. Surg. 2012, 203 (3), 347–51; discussion 351–2.

Khuri SF, Najjar SF, Daley J, Krasnicka B, Hossain M, Henderson WG, Aust JB, Bass B, Bishop MJ, Demakis J, DePalma R, Fabri PJ, Fink A, Gibbs J, Grover F, Hammermeister K, McDonald G, Neumayer L, Roswell RH, Spencer J, Turnage RH, Comparison of surgical outcomes between teaching and nonteaching hospitals in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Ann. Surg. 2001, 234 (3), 370–82; discussion 382–3.

Krell RW, Birkmeyer NJ, Reames BN, Carlin AM, Birkmeyer JD, Finks JF, Effects of resident involvement on complication rates after laparoscopic gastric bypass. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014, 218 (2), 253–60.

Scarborough JE, Pappas TN, Cox MW, Bennett KM, Shortell CK, Surgical trainee participation during infrainguinal bypass grafting procedures is associated with increased early postoperative graft failure. J. Vasc. Surg. 2012, 55 (3), 715–20.

Scarborough JE, Bennett KM, Pappas TN, Defining the impact of resident participation on outcomes after appendectomy. Ann. Surg. 2012, 255 (3), 577–82.

Fanous M, Carlin A, Surgical resident participation in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y bypass: Is it safe? Surgery 2012, 152 (1), 21–5.

Matulewicz RS, Pilecki M, Rambachan A, Kim JY, Kundu SD, Impact of resident involvement on urological surgery outcomes: an analysis of 40,000 patients from the ACS NSQIP database. J. Urol. 2014, 192 (3), 885–90.

Mizrahi I, Mazeh H, Levy Y, Karavani G, Ghanem M, Armon Y, Vromen A, Eid A, Udassin R, Comparison of pediatric appendectomy outcomes between pediatric surgeons and general surgery residents. J. Surg. Res. 2013, 180 (2), 185–190.

Naiditch JA, Lautz TB, Raval MV, Madonna MB, Barsness KA, Effect of resident postgraduate year on outcomes after laparoscopic appendectomy for appendicitis in children. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. A 2012, 22 (7), 715–9.

Patel SP, Gauger PG, Brown DL, Englesbe MJ, Cederna PS, Resident participation does not affect surgical outcomes, despite introduction of new techniques. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2010, 211 (4), 540–5.

Relles DM, Burkhart RA, Pucci MJ, Sendecki J, Tholey R, Drueding R, Sauter PK, Kennedy EP, Winter JM, Lavu H, Yeo CJ, Does resident experience affect outcomes in complex abdominal surgery? Pancreaticoduodenectomy as an example. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2014, 18 (2), 279–85; discussion 285.

Ross SW, Oommen B, Kim M, Walters AL, Green JM, Heniford BT, Augenstein VA, A little slower, but just as good: postgraduate year resident versus attending outcomes in laparoscopic ventral hernia repair. Surg. Endosc. 2014, 28 (11), 3092–100.

Singh P, Turner EJ, Cornish J, Bhangu A, Safety assessment of resident grade and supervision level during emergency appendectomy: analysis of a multicenter, prospective study. Surgery 2014, 156 (1), 28–38.

Venkat R, Valdivia PL, Guerrero MA, Resident participation and postoperative outcomes in adrenal surgery. J. Surg. Res. 2014, 190 (2), 559–64.

Whealon MD, Young MT, Phelan MJ, Nguyen NT, Effect of resident involvement on patient outcomes in complex laparoscopic gastrointestinal operations. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2016, 223 (1), 186–92.

Fahrner R, Turina M, Neuhaus V, Schob O, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy as a teaching operation: comparison of outcome between residents and attending surgeons in 1,747 patients. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2012, 397 (1), 103–10.

Hutter MM, Glasgow RE, Mulvihill SJ, Does the participation of a surgical trainee adversely impact patient outcomes? A study of major pancreatic resections in California. Surgery 2000, 128 (2), 286–92.

Saliba AN, Taher AT, Tamim H, Harb AR, Mailhac A, Radwan A, Jamali FR, Impact of Resident Involvement in Surgery (IRIS-NSQIP): Looking at the bigger picture based on the American College of Surgeons-NSQIP Database. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2016, 222 (1), 30–40.

Seib CD, Greenblatt DY, Campbell MJ, Shen WT, Gosnell JE, Clark OH, Duh QY, Adrenalectomy outcomes are superior with the participation of residents and fellows. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2014, 219 (1), 53–60.

Yaghoubian A, de Virgilio C, Lee SL, Appendicitis outcomes are better at resident teaching institutions: a multi-institutional analysis. The American Journal of Surgery 2010, 200 (6), 810–813.

Obama B, United states health care reform: progress to date and next steps. JAMA 2016.

Ferraris VA, Harris JW, Martin JT, Saha SP, Endean ED, Impact of Residents on Surgical Outcomes in High-Complexity Procedures. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2016, 222 (4), 545–55.

Wilkiemeyer M, Pappas TN, Giobbie-Hurder A, Itani KM, Jonasson O, Neumayer LA, Does resident post graduate year influence the outcomes of inguinal hernia repair? Ann. Surg. 2005, 241 (6), 879–82; discussion 882–4.

Stitzenberg KB, Sheldon GF, Progressive specialization within general surgery: adding to the complexity of workforce planning. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2005, 201 (6), 925–32.

Kelz RR, Sellers MM, Reinke CE, Medbery RL, Morris J, Ko C, Quality in-training initiative—a solution to the need for education in quality improvement: results from a survey of program directors. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2013, 217 (6), 1126–1132.e5.

Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M, Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery 2005, 138 (1), 8–13.

Castleberry AW, Clary BM, Migaly J, Worni M, Ferranti JM, Pappas TN, Scarborough JE, Resident education in the era of patient safety: a nationwide analysis of outcomes and complications in resident-assisted oncologic surgery. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2013, 20 (12), 3715–24.

Kiran RP, Ahmed Ali U, Coffey JC, Vogel JD, Pokala N, Fazio VW, Impact of resident participation in surgical operations on postoperative outcomes: National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Ann. Surg. 2012, 256 (3), 469–75.

Raval MV, Wang X, Cohen ME, Ingraham AM, Bentrem DJ, Dimick JB, Flynn T, Hall BL, Ko CY, The influence of resident involvement on surgical outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2011, 212 (5), 889–98.

Schmidt CM, Turrini O, Parikh P, House MG, Zyromski NJ, Nakeeb A, Howard TJ, Pitt HA, Lillemoe KD, Effect of hospital volume, surgeon experience, and surgeon volume on patient outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a single-institution experience. Arch. Surg. 2010, 145 (7), 634–40.

Hogg ME, Zenati M, Novak S, Chen Y, Jun Y, Steve J, Kowalsky SJ, Bartlett DL, Zureikat AH, Zeh HJ, 3rd, Grading of surgeon technical performance predicts postoperative pancreatic fistula for pancreaticoduodenectomy independent of patient-related variables. Ann. Surg. 2016.

Linn JG, Hungness ES, Clark S, Nagle AP, Wang E, Soper NJ, General surgery training without laparoscopic surgery fellows: the impact on residents and patients. Surgery 2011, 150 (4), 752–8.

Author Contribution

Carr: data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafting; final approval; agreement to be accountable

Chung: data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; drafting; final approval; agreement to be accountable

Schmidt II: design concept; data acquisition; critical revision; final approval; agreement to be accountable

Jester: design concept; critical revision; final approval; agreement to be accountable

Kilbane: data acquisition; critical revision; final approval; agreement to be accountable

House: design concept; critical revision; final approval; agreement to be accountable

Zyromski: design concept; critical revision; final approval; agreement to be accountable

Nakeeb: design concept; critical revision; final approval; agreement to be accountable

Schmidt: design concept; critical revision; final approval; agreement to be accountable

Ceppa: design concept; data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation; critical revision; final approval; agreement to be accountable

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carr, R.A., Chung, C.W., Schmidt, C.M. et al. Impact of Fellow Versus Resident Assistance on Outcomes Following Pancreatoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg 21, 1025–1030 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-017-3383-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-017-3383-4