Abstract

Background

The goal of this study was to determine the impact of mesenteric defect closure and Roux limb position on the rate of internal hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB).

Methods

A retrospective review was conducted of all LRYGB patients from 2001 to 2011 who had all internal hernia (IH) defects closed (DC) or all defects not closed (DnC).

Results

Of 914 patients, 663 (72.5 %) had DC vs. 251 (27.5 %) with DnC, and 679 (74.3 %) had an ante-colic vs. 235 (25.7 %) with a retro-colic Roux limb. Forty-six patients (5 %) developed a symptomatic IH. Of these, 25 (3.8 %) were in the DC vs. 21 (8.4 %) in the DnC group (p = 0.005), and 26 (3.8 %) were in the ante-colic vs. 20 (8.5 %) in the retro-colic Roux limb position (p = 0.005). Data from 45 patients were available for further analysis. The most common symptom was chronic postprandial abdominal pain (53.4 %). All patients underwent CT scan consistent with IH in 26 patients (57.5 %), suggestive in 7 (15.6 %), showing small bowel obstruction in 4 (8.9 %), and negative in 8 (17.8 %).

Conclusions

Closure of mesenteric defects and ante-colic Roux limb position result in a significantly lower IH rate. Furthermore, a high index of suspicion must be maintained since symptoms may be nonspecific and imaging may be negative in nearly 20 % of patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since first described in 1994, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) stands today as the preferred bariatric procedure due to its favorable and durable outcomes.1–7 Although LRYGB has several advantages over the open approach, a higher incidence of early and late postoperative small bowel obstruction has been described.8–12 In fact, while the rate of postoperative small bowel obstruction is reported to be 1 to 3 % in the open approach, it ranges between 1.5 and 11 % in the laparoscopic approach, with most series reporting rates of 4–5 %.9–12 The most common cause of small bowel obstruction after LRYGB is internal hernia accounting for 42–61 % of cases, followed by adhesive disease and jejuno-jejunostomy stenosis.10–12 The increased incidence of internal hernia seen in LRYGB has been attributed to the reduced adhesion formation with laparoscopy.13 Closure vs. nonclosure of the mesenteric defects and ante-colic vs. retro-colic positioning of the Roux limb are major technical considerations that may affect the incidence of internal hernia. The goal of this study was to compare the rate of symptomatic internal hernia in our patients with respect to closure of mesenteric defects and Roux limb positioning, as well as to determine the symptoms and characteristics of internal hernia after LRYGB.

Methods

Patients

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. A retrospective chart review of a prospectively maintained database was conducted of all patients who underwent LRYGB at our institution from 2001 to 2011. Only patients who had all defects closed or no defects closed were included. Patients who had an incidentally identified internal hernia at the time of another operation were also excluded. Data collected included age, sex, preoperative weight, and body mass index (BMI), as well as operative time, positioning of the Roux limb, closure of the mesenteric defects, and length of hospital stay. Postoperative data collected included last documented follow-up visit; weight, BMI, and percent excess weight loss (%EWL) at the time of that visit; and whether the patient had an internal hernia diagnosed during the follow-up period. If a symptomatic internal hernia was diagnosed, the interval to diagnosis and the weight, BMI, and %EWL at the time of diagnosis were collected. The clinical and CT scan findings at presentation were also collected. Details of the internal hernia repair were recorded including the type of admission (emergency vs. elective), type of operation (laparoscopic vs. open), operative time, length of hospital stay, internal hernia site, and whether there was bowel incarceration or strangulation.

Operative Technique

In brief, the gastric pouch size of ≤30 mL and the vertical orientation with the gastro-jejunostomy constructed over a 34-French bougie using a laparoscopic linear cutting stapler and intracorporeal closure of the common opening remained constant throughout the period of the study. The biliopancreatic limb was uniformly 40 cm, and the length of the Roux limb was 100 cm for BMI <50 kg/m2 or 150 cm for BMI ≥50 kg/m2. The jejuno-jejunostomy was constructed using a linear cutting stapler with the common enterotomy closed using a hand-sewn or stapled technique. This jejuno-jejunostomy results in a potential hernia defect in the small bowel mesentery called the mesomesenteric defect.

Early in our practice, the majority of Roux limbs were fashioned in a retro-colic and retro-gastric position. This technique results in two potential hernia sites, one through the transverse colon mesentery called the mesocolic defect and another between the Roux limb and the transverse colon mesentery called Petersen's defect. However, as of 2003, most were constructed in an ante-colic and ante-gastric position. This technique results in one mesenteric defect between the Roux limb and the transverse colon mesentery, Petersen's defect. Initially, running absorbable sutures were used to close the mesenteric defects, but running nonabsorbable sutures have been used since 2004.

Statistical Analysis

Parametric or nonparametric data analysis was conducted depending upon the distribution of the variables. Continuous data are presented as the median. Pearson chi-square, Fisher's exact test, and ANOVA tables were utilized, and a p value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariate analysis adjusting for preoperative demographics was also used to test the hypothesis. All analysis was conducted using SAS (version 9.2) and SPSS (version 16) statistical software.

Results

Between 2001 and 2011, there were 1,160 patients who underwent LRYGB at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Of these, 914 patients met the inclusion criteria with 663 patients (72.5 %) having all defects closed (DC) and 251 (27.5 %) having no defects closed (DnC) (Table 1). Of the 914 patients, 679 patients had an ante-colic Roux limb with the majority having all defects closed except in 22 (3.2 %) and 235 patients had a retro-colic Roux limb and no defects closed except in 6 (2.6 %), again reflecting the evolving practice. Data were further analyzed based on closure of mesenteric defects, although we acknowledge that there is no way to separate the impact of closure of defects from the position of the Roux limb in our dataset.

The median age was 42 years (range, 14–73), and there were 728 females (79.6 %) vs. 186 males (20.4 %). The median preoperative weight was 293 lbs (range, 183–555), and BMI was 48 kg/m2 (range, 32–84). The median operative time was 110 min (range, 62–335), with the DC group taking a statistically significant longer time by 15 min (p < 0.0001). The median hospital stay was 2 days (range, 1–9). There was follow-up data available for 869 (95.1 %) patients with a median follow-up interval of 24.9 months (range, 0.5–131). The DC group had a shorter hospital stay (p < 0.0001) and a shorter follow-up interval (p < 0.0001), most likely as a result of a maturing practice and the shift in technique from DnC to DC later in time. At the last follow-up visit, there was no significant difference between the two groups in weight, BMI, or %EWL.

Internal Hernia

Of these 914 patients, 46 (5 %) developed a symptomatic internal hernia that required primary surgical intervention. This incidence was significantly lower in the DC group, 25 of 663 patients (3.8 %), vs. the DnC group, 21 of 251 patients (8.4 %) (p = 0.005). This difference remained statistically significant on multivariate analysis adjusting for age and sex (p = 0.0098, OR 0.44, 95 % CI 0.24–0.82). As expected, the incidence was also significantly lower in the ante-colic vs. retro-colic Roux limb group (3.8 % vs. 8.5 %, respectively; p = 0.005). One of the 46 patients developed a symptomatic hernia when he was in a different state. Open repair was performed, but there was no data available concerning the clinical presentation or intraoperative findings. The remaining 45 patients were subject to secondary review and analysis.

Both DC and DnC groups were comparable in terms of age, sex, preoperative weight, and BMI (Table 2). However, the DC group had a statistically significant shorter follow-up interval at 40.6 months (range, 13–90) vs. the DnC group at 73 months (range, 17–113) (p = 0.001). Again, this is most likely attributable to the shift in technique from DnC to DC later in time. However, the interval to the development of a symptomatic internal hernia was significantly shorter for the DC vs. DnC group (16.6 months (range, 3–72) vs. 33.5 months (range, 10–103), respectively; p < 0.0001). The reasons for this are unclear but may be related to later increased vigilance and a decreased threshold for evaluating for an internal hernia. At the time of internal hernia repair, there was no difference between the groups in weight, BMI, or %EWL.

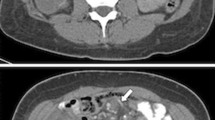

The clinical presentation and CT scan findings are shown in Table 3. The most common symptom was vague postprandial abdominal pain (24 patients (53.4 %)), followed by abdominal pain associated with nausea (8 (17.8 %)) and abdominal pain associated with nausea and vomiting (8 (17.8 %)). Two patients (4.4 %) presented with acute abdominal pain without nausea or vomiting, two patients (4.4 %) presented with acute abdominal pain with nausea and vomiting, and one patient (2.2 %) presented with peritonitis and an acute surgical abdomen after being misdiagnosed at an outside hospital. All 45 patients had a diagnostic CT scan performed prior to surgical exploration. The CT scan was consistent with the presence of an internal hernia in 26 patients (57.5 %), suggestive in 7 patients (15.6 %), and demonstrated the presence of small bowel obstruction without a specific reason in 4 patients (8.9 %). Eight patients (17.8 %) had negative CT scan findings.

Twenty-six patients (57.8 %) had an elective admission and 19 patients (42.2 %) had an emergency admission (Table 4). At the time of operation, 39 cases (86.7 %) were repaired laparoscopically and 6 (13.3 %) had open exploration and repair. Small bowel incarceration was identified at 27 hernia sites (38 %) and strangulation at 1 site (1.4 %). Of the 45 patients who developed a symptomatic internal hernia, there were 5 internal hernias at the mesocolic site, 40 at the Peterson space, and 26 at the mesomesenteric site. Two patients (4.4 %) required small bowel resection. The median operative time was 104 min (range, 75–180), and the median hospital stay was 1 day (range, 0.5–32). There was one mortality (2.2 %) in the patient who presented in extremis and fulminant liver failure after being hospitalized elsewhere for 3 days with the incorrect diagnosis. One patient had recurrence of an internal hernia 43 months after repair, and another patient had recurrence twice 11.5 and 14.2 months after initial hernia repair. All three recurrences required urgent open exploration. These recurrences indicate that the mesenteric defects reopened or were not adequately closed at the time of initial or subsequent repair.

Discussion

LRYGB has largely replaced the open approach due to improved outcomes in postoperative pain, length of stay, and perioperative morbidity.2–6 Roux-en-Y reconstruction of the alimentary tract creates defects in the mesentery or potential internal hernia sites. In the retro-colic retro-gastric technique, three mesenteric defects are created: the mesocolic defect where the alimentary limb traverses the mesocolon into the lesser sac, Petersen's defect between the mesentery of the alimentary limb and the transverse mesocolon, and the mesomesenteric defect at the jejuno-jejunostomy between the mesenteries of the alimentary limb and the biliopancreatic limb and common channel. In the ante-colic ante-gastric technique, two mesenteric defects are created: Petersen's and mesomesenteric defects. Similar to the open operation, the Roux limb was passed retro-colic and mesenteric defects were not routinely closed in the early experience with LRYGB. However, unlike the open approach, the laparoscopic approach resulted in a higher incidence of internal hernia ranging from 0 to 11 % thought to be due to decreased adhesion formation.9–14 In this study, we examined the impact of closure of the mesenteric defects and Roux limb position on the incidence of symptomatic internal hernia. We report an overall incidence of symptomatic internal hernia of 5 % after LRYGB, with a statistically significant lower incidence when all of the defects were closed with an ante-colic Roux limb vs. not closed with a retro-colic limb.

An internal hernia is a potentially life-threatening complication, and there has been considerable debate throughout the history of LRYGB regarding technical considerations to decrease its incidence. There is general consensus that ante-colic ante-gastric placement of the Roux limb decreases the rate of internal hernia when compared to retro-colic retro-gastric placement.12,15–18 This makes intuitive sense since there is no mesocolic defect with ante-colic ante-gastric placement. Importantly, there are reports of a three- to tenfold higher incidence of small bowel obstruction with retro-colic vs. ante-colic positioning of the Roux limb due to both a higher incidence of internal hernia and cicatrization at the mesocolic window.12,19 However, advocates of the retro-colic retro-gastric approach have suggested that careful defect closure may result in a decreased internal hernia rate.14

Consistent with our data, most studies have shown decreased rates of internal hernia with closure of defects and most authors have advocated closure of the mesenteric defects.14,20,21 However, Abasbassi et al. have suggested that only the mesomesenteric defect needs to be closed, citing higher rates of internal hernia here.20 This finding has not been consistent among studies with other reports demonstrating higher rates in the mesocolic or Petersen's defect than at the jejuno-jejunostomy.22–24 Bauman and Pirrello investigated internal hernia at Petersen's space and found an incidence of 6.2 % without closure vs. 0 % since 2006 when they started closing Petersen's space.24

Other technical considerations aside from defect closure have been described to impact the rate of internal hernia. Nandipati et al. showed that construction of the Roux limb with counterclockwise rotation of the bowel so that both the jejuno-jejunostomy and ligament of Treitz are to the left of the axis of the mesentery significantly reduces the incidence of internal hernias at Petersen's defect (0 % vs. 9.2 %, p = 0.043).25 Bauman and Pirrello suggested that there is a decrease in incidence of Petersen's hernias with a short biliopancreatic limb length (50 cm) vs. a longer limb length (100 cm).24 Madan et al. have suggested that defects do not need to be closed, reporting an internal hernia rate of 0 % at a median follow-up of 23.5 months (range, 1–60).18 Notably, they emphasize that there are other technical considerations that may impact internal hernia incidence such as (1) ante-colic ante-gastric Roux limb, (2) minimal division of the small bowel mesentery, (3) a long jejuno-jejunostomy, (4) division of the omentum, (5) configuration of the Roux limb and the biliopancreatic limb, and (6) placement of the jejuno-jejunostomy above the colon in the left upper quadrant.

Our study has several limitations. First, it is a retrospective review comparing the impact of defect closure with a historical control group early in the practice when defects were not routinely closed. As a result, the length of follow-up was significantly shorter for the DC vs. DnC group (p = 0.001). However, the time to develop an internal hernia was also significantly shorter for the DC vs. DnC group (p < 0.0001). The reason for this is not entirely clear but may be related to later increased vigilance and a decreased threshold for evaluating for an internal hernia. With regard to technical considerations, most operations were performed by a single surgeon whose practice did evolve over time from a retro-colic retro-gastric Roux limb without closure of mesenteric defects to an ante-colic ante-gastric Roux limb with closure of mesenteric defects. As a result, the greatest limitation of our study is that we could not separate the impact of defect closure from Roux limb position to determine the contribution of either alone in the incidence of internal hernia. Further, our study only investigated the rate of symptomatic internal hernia, and internal hernias that were incidentally repaired during another operation were not included. Finally, there is no way to capture patients who may have been lost to follow-up and treated elsewhere for internal hernia. Overall, this number is likely low since most of our patients are referred back to us when they present to outside regional hospitals or develop any complication. Regardless, there is no reason to suspect a difference between the two groups, that is, a higher number of patients with all defects closed vs. no defects closed presenting to outside hospitals.

Conclusion

In conclusion, internal hernia is a potentially life-threatening complication that can present at any time ranging from a few weeks to several years after LRYGB. A high index of suspicion must be maintained since symptoms may be nonspecific and imaging may be negative. It is our current practice to perform (1) an ante-colic ante-gastric Roux limb with (2) counterclockwise rotation of the alimentary limb so the stapled end faces the left upper quadrant, (3) division of the omentum, (4) 40-cm biliopancreatic limb, and (5) routine closure of Petersen's and the mesomesenteric defects using nonabsorbable suture. Although closure of defects and ante-colic positioning of the Roux limb does not eliminate the risk of internal hernia, our data support that each may be a key factor in reducing the incidence of internal hernias.

References

Wittgrove AC, Clark GW, Tremblay LJ. Laparoscopic gastric bypass, Roux-en-Y: preliminary report of five cases. Obes Surg 1994;4:353–357.

Nguyen NT, Goldman C, Rosenquist CJ, Arango A, Cole CJ, Lee SJ, Wolfe BM. Laparoscopic versus open gastric bypass: a randomized study of outcomes, quality of life, and costs. Ann Surg 2001;234:279–289.

Luján JA, Frutos MD, Hernández Q, Liron R, Cuenca JR, Valero G, Parrilla P. Laparoscopic versus open gastric bypass in the treatment of morbid obesity: a randomized prospective study. Ann Surg 2004;239:433–437.

Smith SC, Edwards CB, Goodman GN, Halversen RC, Simper SC. Open vs. laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: comparison of operative morbidity and mortality. Obes Surg 2004;14:73–76.

Hutter MM, Randall S, Khuri SF, Henderson WG, Abbott WM, Warshaw AL. Laparoscopic versus open gastric bypass for morbid obesity: a multicenter, prospective, risk-adjusted analysis from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Ann Surg 2006;243:657–666.

Jones KB Jr, Afram JD, Benotti PN, Capella RF, Cooper CG, Flanagan L, Hendrick S, Howell LM, Jaroch MT, Kole K, Lirio OC, Sapala JA, Schuhknecht MP, Shapiro RP, Sweet WA, Wood MH. Open versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a comparative study of over 25,000 open cases and the major laparoscopic bariatric reported series. Obes Surg 2006;16:721–727.

Obeid A, Long J, Kakade M, Clements RH, Stahl R, Grams J. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: long term clinical outcomes. Surg Endosc 2012;26:3515–3520.

Blachar A, Federle M, Pealer K, Ikramuddin S, Schauer P. Gastrointestinal complications of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: clinical and imaging findings. Radiology 2002;223:625–632.

Podnos YD, Jimenez JC, Wilson SE, Stevens CM, Nguyen NT. Complications after laparoscopic gastric bypass: a review of 3464 cases. Arch Surg 2003;138:957–961.

Nguyen N, Huerta S, Gelfand D, Stevens M, Jeffrey J. Bowel obstruction after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2004;14:190–196.

Husain S, Ahmed A, Johnson J, Boss T, O’Malley W. Small bowel obstruction after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Arch Surg 2007;142:988–993.

Koppman JS, Li C, Gandas A. Small bowel obstruction after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: A review of 9,527 patients. J Am Coll Surg 2008;206:571–584.

Garrard CL, Clements RH, Nanney L, Davidson JM, Richards WO. Adhesion formation is reduced after laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc 1999;13:10–13.

Miyashiro L, Fuller W, Ali M. Favorable internal hernia rate is achieved using retrocolic, retrogastric alimentary limb in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2010;6:158–164.

Cho M, Pinto D, Carrodeguas L, Lascano C, Soto F, Whipple O, Simpfendorfer C, Gonzalvo JP, Zundel N, Szomstein S, Rosenthal RJ. Frequency and management of internal hernias after laparoscopic antecolic antegastric Roux-en-Y gastric bypass without division of the small bowel mesentery or closure of mesenteric defects: review of 1400 consecutive cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2006;2:87–91.

Escalona A, Devaud N, Gustavo P, Crovari F, Boza C, Viviani P, Ibanez L, Guzman S. Antecolic versus retrocolic alimentary limb in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a comparative study. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2007;3:423–427.

Finnell CW, Madan AK, Tichansky DS, Ternovits C, Taddeucci R. Non-closure of defects during laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2007;17:145–148.

Madan A, Lo Menzo E, Dhawan N, Tichansky D. Internal hernia and nonclosure of mesenteric defects during laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2009;19:549–552.

Champion JK, Williams M. Small bowel obstruction and internal hernias after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2003;13:596–600.

Abasbassi M, Pottel H, Deylgat B, Vansteenkiste F, Van Rooy F, Devriendt D, et al. Small bowel obstruction after antecolic antegastric laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass without division of small bowel mesentery: a single center, 7 year review. Obes Surg 2011; 21: 1822–1827.

de la Cruz-Munoz, Cabrera C, Cuesta M, Hartnett S, Rojas R. Closure of mesenteric defect can lead to decrease in internal hernias after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2011; 7: 176–180.

Filip JE, Mattar SG, Bowers SP, Smith CD. Internal hernia formation after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Am Surgeon 2002;68:640–643.

Iannelli A, Facchiano E, Gugenheim J. Internal hernia after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Obes Surg 2006;16:1265–1271.

Bauman RW, Pirrello JR. Internal hernia at Petersen’s space after laparoscopic roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 6.2% incidence without closure – a single surgeon series of 1047 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2009;5:565–570.

Nandipati K, Lin E, Husain F, Srinivasan J, Sweeney J, Davis S. Counterclockwise rotation of Roux-en-Y limb significantly reduces internal herniation in laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB). J Gastrointest Surg 2012;16:675–681.

Facchiano E, Iannelli A, Gugenheim J, Msika S. Internal hernias and nonclosure of mesenteric defects during laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2010;20:676–678.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Discussant

Dr. Thomas Aloia (Houston, TX): This study examines a single-surgeon, large-volume experience with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. The focus is on the prevention of the postoperative complication of internal hernia. As the technique has evolved, mainly with higher utilization of mesenteric defect closure and anticolic anastomosis, the authors have observed a reduction in internal hernia rates. It is noted that due to issues including geography, access to care, and vigilance on the part of the operative team, there is very thorough long-term follow-up data to address this issue.

Although I am not a bariatric surgeon, I do take general surgery emergency call in a city with over 20 bariatric surgery centers, many of which do not enjoy the rigorous follow-up that returns the sick postoperative patient to their home surgical center, as happens in your area. I have found the presentation and management of this problem to be very difficult, and therefore, I am supportive of any and all maneuvers that can be done to prevent these complications. What I have learned from caring for these patients is that a high level of suspicion for the diagnosis of internal hernia should be held for any post-LRYGB patient with a complaint of abdominal pain, regardless of imaging findings.

Ultimately, I have three questions:

1. The nuances of your technique have evolved over time. Were the individual decisions to change directly driven by an intent to reduce internal hernias or were they aimed at another outcome, such as decreasing operative time, and the reduction of internal hernias was a fortuitous bystander effect?

2. In the discussion, it appears that there is a trend toward consensus that the maneuvers you have adopted do reduce this complication, but a handful of studies are quoted that find no such relationship. Can you explain why surgeons who do not close mesenteric defects do not see problems with internal hernias? Could it be that their follow-up is less rigorous than yours?

3. For the benefit of the trainees, and even the full-fledged nonbariatric surgeons in the audience, can you describe the proper operative approach to the LRYGB patient with an internal hernia?

Closing Discussant

Dr. Ayman Obeid: Thank you for the valuable comments and the intriguing questions.

Regarding your first question, the changes in the practice were indeed made with the intent to reduce the incidence of internal hernias. As a matter of fact, LRYGB evolved from open RYGB, a technique in which retro-colic positioning of the Roux limb was routine practice as well as nonclosure of mesenteric defects. Given more experience with the laparoscopic approach, surgeons began reporting higher internal hernia rates, a complication that was rare with the open approach. Thus, many surgeons, including our practice, started routinely closing these defects with the thought that the higher incidence was due to the decreased adhesion formation in the laparoscopic approach. Again, as more experience was gained with the laparoscopic approach, we learned that most Roux limbs could be positioned in ante-colic fashion without undue tension at the gastro-jejunostomy, especially with splitting of the omentum. This change did have the benefit of eliminating one of the potential hernia sites (mesocolic defect) and potentially decreasing operative time. The shift to closure of the defects and ante-colic Roux limb positioning in our practice actually resulted in an increased total OR time by about 15 min.

With respect to the second question regarding studies that do not advocate for closure of the defects, certainly duration of and compliance with follow-up may play a role. Internal hernia may present at any time from a few months to several years after LRYGB, and we know that long-term follow-up in these patients tends to be poor, with studies reporting 40–70 % loss to follow-up at 2 years. In the study by Finnell et al. in 2007 reporting their rate of internal hernia at 0 % with nonclosure of the defects, the sample size was 300 patients and the follow-up was 18 months (range, 1–44). In their subsequent study by Madan et al. in 2009, the follow-up period was 23.5 months (range, 1–60) in 387 patients. Our overall follow-up was 25 months (range, 1–131) in a sample size of 914 patients. For the patients who developed a symptomatic internal hernia in our cohort, the median follow-up was 56 months (range, 13–113). There was also a difference in how we defined “internal hernia.” In their 2009 study, Madan et al. did report that 2/54 (3.7 %) patients had a “potential” defect behind the Roux limb and the defect was closed in one of these two patients. They did not count these as “internal hernias” since they were merely open and potential spaces. In our study, we counted any open defect in a symptomatic patient as an internal hernia. We would also refer you to the Letter to the Editor by Facchiano et al. 26 in Obesity Surgery in 2010 for further discussion of the Madan et al. 2009 paper.

Additionally, as you suggested, patients may not return to their home surgical institution for evaluation of complications. In Alabama, we are the major tertiary referral center, and many other centers will not operate on our patients unless on an absolutely emergent basis. Most contact us for transfer, even if >3 h away. Many outside surgeons will also not evaluate our bariatric patients electively (for the chronic presentations), and they end up finding their way back to us as well, even if they were otherwise lost to follow-up.

Lastly, there may be other technical considerations aside from defect closure that may impact the rate of internal hernia and may account for the decreased rates seen with nonclosure of the defects in some studies. Finnell et al. and others have cited other technical considerations such as ante-colic positioning, counterclockwise rotation of the bowel with the jejuno-jejunostomy and ligament of Treitz to the left of the axis of the mesentery, short <50-cm biliopancreatic limb length, minimal division of the small bowel mesentery, a long jejuno-jejunostomy, division of the omentum, and placement of the jejuno-jejunostomy above the colon in the left upper quadrant. In our study, all of these other considerations remained constant with the only change in practice being the position of the Roux limb and closure vs. nonclosure of the defects.

Regarding the proper operative approach to the LRYGB patient with an internal hernia, as you mentioned, the presentation and management of this complication can be very challenging. The most important guiding principle is to maintain a high index of suspicion and to have a low threshold for exploration when evaluating a patient with abdominal pain status post LRYGB. If internal hernia is suspected, we start with a thorough history and physical followed by a CT scan. We as surgeons and our radiologists are experienced in specific signs that may indicate an internal hernia, and the CT scan is specifically examined for these findings: mesenteric swirl, mushroom shape of the mesentery, small bowel obstruction, clustered loops of the small bowel, small bowel behind the SMA, and a right-sided jejuno-jejunostomy. However, as our study demonstrated, CT scan findings were negative in almost 20 % of patients. Thus, even if imaging is negative but clinical suspicion remains high, the patient is taken to the operating room to explore for an internal hernia. In terms of the actual operation, one could explore laparoscopically or open based on the surgeon's comfort. It is usually easiest to identify the ileocecal valve and start running the small bowel from distally to proximally since this portion of the intestine will be decompressed, easier to manipulate, and usually in normal anatomic position. The hernia may reduce as this is being performed. If starting proximally, it can be difficult to sort out the Roux limb from the biliopancreatic limb from the common channel and determine whether and which bowel is herniated. If ante-colic, both potential spaces need to be inspected and closed. If retro-colic, all three potential spaces need to be inspected and closed. We recommend a running nonabsorbable suture for closure.

This paper was presented as an oral presentation during Digestive Diseases Week during the SSAT Annual Meeting in Orlando, Florida, on May 18–21, 2013.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Obeid, A., McNeal, S., Breland, M. et al. Internal Hernia After Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y Gastric Bypass. J Gastrointest Surg 18, 250–256 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-013-2377-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-013-2377-0