Abstract

Increased rates of colorectal cancer (CRC) with high rates of progression from dysplasia to CRC are well documented in the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) population. This increased risk in the presence of currently improving but still inadequate surveillance techniques confirms that the cancer “fear” in IBD patients is still real. The majority of data on the cancer risk in IBD has been gathered from ulcerative colitis (UC) patients as these patients are generally better studied. Thus surveillance and treatment protocols for Crohn’s disease (CD) are frequently modeled on UC paradigms. Dysplasia in the IBD cohort frequently is a harbinger of local, distant, or metachronous neoplasia. Therefore, frequent surveillance and referral for surgical intervention when dysplasia is detected are justified in both the CD and UC patient.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

An increased risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) is seen in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients compared to the general population. This risk is substantial with CRC documented as the cause of death in up to 15 % of IBD patients.1 Studies on dysplasia and cancer in ulcerative colitis (UC) are more widely available than those on Crohn's disease (CD), thus surveillance and treatment paradigms are often similar in the two groups despite differing disease pathophysiologies. However, notably, CD patients have an increased incidence of non-colorectal cancers such as small bowel carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in anal fistuli which may influence surveillance and treatment regimes.2 In both UC and Crohn's colitis, incidence of CRC is increased in those with greater extent of disease, longer disease duration, family history of CRC3,4 and in the presence of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC).5 The average age of CRC diagnosis in the colitic patient is 50–52 and is similar in CD and UC and is approximately 15 years younger than the average age of those diagnosed with sporadic cancer.6,7

Although the general consensus is that of an increased CRC risk in IBD, controversially, a 2012 Danish study using their national registry documented no overall increased risk of CRC when comparing all UC and CD patients to the general population. However, risk was seen to be increased in subpopulations, i.e., those with PSC or a childhood diagnosis of IBD. This study also showed a decrease in the incidence of CRC in the IBD population since the 1980s, a likely result of new medical therapy and increased awareness and surveillance leading to earlier diagnosis and treatment.5

CRC Incidence in CD

Two large meta-analyses of CRC in CD including over 100,000 patients have been performed to date. The first, performed in 2007 by Von Roon et al., documented a relative risk of colon cancer of 2.59 in CD patients compared to the general population.8 Laukoetter et al.'s subsequent 2011 meta-analysis confirmed this figure demonstrating a 2–3× increased rate of CRC in CD vs the non IBD population, with an average disease duration of 18.3 years from CD diagnosis to CRC.7 Both meta-analyses similarly showed a significant association between anatomical area of inflammation and cancer location as well as a greatly increased risk of small bowel cancer (with a relative risk of 28.4 and up to 18× that of the general population in each study, respectively). A particularly increased risk of cancer in patients with extensive or total colitis was noted by Gillen et al. who demonstrated that this subgroup of their 281 studied CD patients had an 18-fold increased risk of developing cancer. When these extensive colitis patients were diagnosed in childhood, relative risk was calculated at an extremely elevated 57-fold.9 Studies on rectal cancer in CD, however, vary with some showing no increased risk and others showing a slightly increased risk.6,8–10

CRC in UC

UC CRC rates are slightly greater than CD CRC rates. This is likely due to the greater extent of continuous inflammation present. The largest, most commonly referenced meta-analysis of 116 studies (54,478 IBD patients with 1,698 CRCs diagnosed) performed in 2001demonstrated an overall CRC rate of 3.7 % in all UC patients with increasing cumulative probabilities of 2 % by 10 years, 8 % by 20 years, and 18 % by 30 years.11

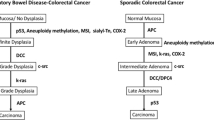

Types of IBD-Associated Dysplasia

Five main types of dysplasia are described in IBD. Classification is based on location and lesion morphology (Table 1). Treatment is guided by each type of dysplasia's risk of synchronous and metachronous lesions and risk of progression to CRC. The current IBD dysplasia–carcinoma model suggests progression from inflamed tissue to low-grade dysplasia (LGD) to high-grade dysplasia (HGD) to carcinoma. However, frequently IBD-associated cancer “skips stages” and HGD or CRC is discovered without prior evidence of LGD. In addition, IBD-associated carcinoma often develops at a more accelerated rate.

Synchronous and Metachronous Lesions

Due to the “field effect” of cellular and molecular changes present throughout the IBD colon, both synchronous and metachronous dysplasia and carcinomas are more common in the IBD population than the sporadic cancer population.6 This suggests the discovery of either cancer or dysplasia to be a marker or “warning” for the presence of other foci. In Kiran et al.'s 2010 study, records of 64 CD and 176 UC patients with CRC were evaluated. A 14 and 4 % synchronous tumor rate and a synchronous dysplasia rate of 55 and 30 % were noted in UC and CD, respectively.12 In other similar studies, synchronous tumors were found in 4–11 % of CD resections and 10–25 % UC resections.13

Often dysplasia and cancer are found concomitantly in resection specimens. Reported rates of distant dysplasia (of any grade) in cases of adenocarcinoma have been as high as 55–74 % in UC and 30–41 % in CD.13,14 Studies vary with a 0–41 % prevalence rate of synchronous CRC in colectomy specimens resected for LGD diagnosed in endoscopic biopsies in IBD patients.15 In Gorfine et al.'s study of the pathology reports of 590 proctocolectomy specimens from UC patients, patients whose colectomy specimens were found to have a focus of dysplasia (HGD or LGD) were 36× more likely to have invasive carcinoma present when compared to patients whose specimens did not contain dysplasia.16

Metachronous lesion rates are more difficult to study due to the practice of excising the colon and rectum in its entirety when neoplasia is found. However, rates have been reported to be as high as 15 % within 4 years in CD patients who had undergone segmental resections.12

LGD

LGD shares several histopathologic features with inflammation, is often difficult to detect colonoscopically, and thus, is most commonly found during random biopsying. Progression from LGD to HGD or CRC has been suggested to be more rapid and more common in those with distal LGD and in those with longstanding, extensive disease as shown in Goldstone et al.'s study which followed the outcomes of 121 UC patients with LGD.17 A 53 % 5-year rate for LGD progressing into cancer or HGD was seen in Ullman's study of 46 UC patients with LGD discovered on surveillance colonoscopy.18 Similarly, Connell found a 5-year predictive value for LGD developing into HGD or CR of 54 % in a study of long-term surveillance of over 300 UC patients.19

Studies documenting lack of progression of dysplasia, such as Befrits et al.'s controversial 2002 study following patients with LGD, compromised by low patient numbers (37 patients) although follow-up was a mean of 10 ± 6 years with a range of 1–22 years, have been performed.20 Another such study included 40 UC patients with LGD on colonoscopy. Patients underwent a combined further 201 colonoscopies (223 patient years follow-up). Half (n = 20) had no further dysplasia (mean 4.0 colonoscopies per patient over 4.7 years), 19 had persistent low-grade dysplasia (mean 6.3 colonoscopies per patient over 6.9 years). and 1 subsequently developed CRC.21 However, such studies are greatly outnumbered by studies demonstrating a high risk of progression, suggesting that LGD should be considered as a likely precursor to CRC.18 LGD discovered on biopsy requires investigation and confirmation by a second pathologist. If agreement between pathologists is not achieved, repeat colonoscopy is required. Once LGD is confirmed, surgery is recommended.

HGD

HGD shares histopathological features with CRC. Due to the high likelihood of progression to CRC, the likelihood of CRC on final colectomy pathology and the high incidence of synchronous tumors (discussed above), HGD is usually resected and therefore, no large studies following HGD patients have been performed. In a small systematic review by Bernstein et al., 32 % (of 47 patients) with HGD on colonoscopy had CRC discovered on resection pathology.22 Thus, all HGD warrants surgical excision.

DALMs

Dysplasia-associated masses or lesions (DALMs) are distinct areas of dysplasia located within IBD-associated inflammation and represent a very high-risk group, particularly sessile DALMs. These lesions are often found to be associated with CRC and are difficult or impossible to remove colonoscopically. In an earlier study, carcinoma was found in 7 of 12 cases of DALM diagnosed on colonoscopic surveillance of 112 UC patients with longstanding disease. Five of these 7 DALMs were single polypoid masses and all 5 contained invasive carcinoma on colectomy pathology. Notably, multiple colonoscopic biopsies of these DALMs did not reveal carcinoma.23 In Bernstein et al.'s small systematic review mentioned above, 43 % of patients diagnosed with DALMs were found to ultimately have CRC.22 Larger longitudinal studies of these difficult to colonoscopically remove DALM lesions have not been done because of these early studies showing the high risk of cancer within the DALM itself and of progression to CRC leading to the strong recommendation that surgical excision is required for all DALMs.

ALMs

Adenoma-like masses (ALMs) are lesions that resemble adenomas in their distinct singular polyp-like morphology but are found in areas lacking inflammation and are amenable to complete endoscopic excision after circumferential biopsy to rule out inflammation. One study of both ALMs and DALMs in 59 highly selected IBD patients, found that carcinoma and dysplasia were found only in the lesions that were found in areas of inflammation, with no cancer or HGD found in patients with ALMs.24 If endoscopic resection of these lesions is performed, subsequent, frequent, thorough colonoscopic surveillance is recommended.25

Adenoma-Like DALMs

Adenoma-like DALMs are polypoid lesions located within an inflamed area but, as opposed to DALMs, are amenable to resection based on their morphology. Adenoma-like DALMs tempt the colonoscopist to resect them endoscopically due to their polypoid appearance. Despite their singular polypoid morphology, they are uncommonly studied as a distinct entity separate to DALMs. One study by Engelsgjerd et al. in 1999 was limited by very small patient numbers but demonstrated approximately 60 % of the 24 UC patients with adenoma-like DALMs developed further adenoma-like DALMs in 4 years of endoscopic follow-up. One developed LGD and none developed CRC. However, this group was highly selected and follow-up was relatively short.26 Recently, a Dutch group reported on the outcomes of 110 IBD patients with “adenomas,” 123 IBD patients without adenomas, and 179 non IBD patients with adenomas. Close analysis of the paper reveals that 81 % (89 out of 110) of the adenomas were located within areas affected by IBD and were therefore at least adenoma-like DALMs, if not real DALMs. Five-year cumulative risk of HGD or CRC was 11 % in the “adenoma” group vs only 3 % in IBD non adenoma patients, again suggesting that adenomas within areas of inflammation (adenoma-like DALMs) predispose to eventual malignancy.27

Based on this limited data, some clinicians advocate close surveillance after colonoscopic removal of an adenoma-like DALM. However, if such is undertaken, surveillance should be very frequent (at least every 6 months) and should be performed by an expert endoscopist with an expert gastrointestinal pathologist examining the biopsies. Both caregivers and patients often choose surgical resection when adenoma-like DALMs are discovered to obviate this burdensome and stressful surveillance need. The various treatment paradigms for IBD-associated dysplasia are summarized in Table 2.

Resection Options for IBD-Associated Neoplasia

Once carcinoma or dysplasia of any type or grade is identified, extensive resection is usually recommended. Total proctocolectomy (TPC) or the excision of the entire colon and rectum is the only surgical procedure that eliminates all current and future lesions in IBD. For the UC patient, either an end ileostomy or ileal anal pouch anastomosis may be created. Due to the segmental nature of CD, less extensive resections may be considered in CD vs UC. However, surgical decision making should consider the surgical fitness of the patient and may result in less than a TPC. A detailed discussion of choice of surgery is beyond the scope of this paper and the reader is referred to Connelly et al.28 In patients who have undergone anything less than a TPC for dysplasia or carcinoma, frequent surveillance of any remaining colon or rectum must be continued. Surgical decision ‘rules’ in dysplasia and IBD are highlighted in Table 3.

Prognosis

Generally, prognosis in IBD patients with CRC is similar to or slightly poorer than that found in the sporadic CRC population. A less than 60 % 5-year survival rate in IBD-CRC with slightly worse survival seen in CD has been documented in multiple studies.12,13 Averboukh et al.'s 13-patient CD–CRC cohort had only a 37 % 5-year survival rate compared to the 40-patient UC–CRC cohort which had a 61 % survival.1 However, most such studies have shown that IBD-associated cancer is often discovered at a later stage with serosal invasion or with nodal or distant metastases.10 In Kirin's 1999 study, approximately 40 and 60 % of UC and CD patients respectively had stage III or IV cancer at the time of their resection. Also, many of the tumors in the Kiran et al. and Sigel et al.'s studies were poorly differentiated on final pathology.12,14

Conclusion

Yes, the fear of colorectal cancer in the IBD patient is still real. Endoscopic surveillance techniques are improving, molecular diagnostic research is ongoing that may, in the future, identify at risk patients earlier leading to more effective prophylactic care. However, at this time, frequent surveillance, a high index of suspicion for lesions detected, and extensive resection are warranted in this selected patient cohort.

References

Averboukh F, Ziv Y, Zmora O et al. Colorectal carcinoma in inflammatory bowel disease: a comparison between Crohn's and ulcerative colitis. Colorectal Disease 2011; 13, 1230-1236

Friedman, S. Cancer in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2006; 35:621-639

Nuako KW, Ahlquist DA, Mahoney DW et al . Familial predisposition for colorectal cancer in chronic ulcerative colitis: a case-control study. Gastroenterology 1998; 114:669-674

Eaden J, Abrams K, Ekbom A, Jackson E, Mayberry J. Colorectal cancer prevention in ulcerative colitis: a case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000; 14:145-153

Jess T, Simonsen J, Jorgensen KT et al. Decreasing risk of colorectal cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease over 30 years. Gastroenterology 2012; 143:375–381

Svrcek M, Cosnes J, Beaugerie L. et al. Coloretal neoplasia in Crohn's colitis: a retrospective comparative study with ulcerative colitis. Histopathology 2007; 50: 574-583

Laukoetter MG, Mennigen R, Hannig C et al. Intestinal cancer risk in Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis. J Gastrointestinal Surg 2011; 15:576-583

Von Roon A, Reese G, Teare J et al. The risk of cancer in patients with Crohn's disease. Dis Col Rect 2007;50: 839-855

Gillen Cd, Andrews HA, Prior P et al. Crohn's disease and colorectal cancer. Gut 1994;35:651-655

Freeman H. Colorectal cancer complicating Crohn's Disease. Can J Gastroenterol 2001;15: 231-236

Eaden JA, Abramsb KR, Mayberry JF. The risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis. Gut 2001:48: 526-535

Kiran RP, Khoury W, Church JM, Lavery IC, Fazio VW and Remzi FH. Colorectal cancer complicating inflammatory bowel disease. Similarities and differences between Crohn's and ulcerative colitis based on decades of experience. Annals of Surg 2010; 252: 330-335

Choi PM and Zelig MP. Similarity of colorectal cancer in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: implications for carcinogenesis and prevention. Gut 1994; 35:950-954

Sigel JE, Petras RE, Lashner BA, Fazio VW an Goldblum JR. Intestinal adenocarcinoma in Crohn's Disease: a report of 30 cases with a focus on coexisting dysplasia. The Am. J. of Surg. Pathology 1999; 23:651-655

Farraye FA, Odze RD, Eaden J, et al. AGA medical position statement on the diagnosis and management of colorectal neoplasia in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2010;138:738-745

Gorfine Sr, Bauer JJ, Harris MT et al. Dysplasia complicating chronic ulcerative colitis; is immediate colectomy warranted? Dis col Rectum 2000;43: 1575-81

Goldstone R, Itzkowitz S, Harpaz N and Ullman T. Progression of low-grade dysplasia in ulcerative colitis: effect of colonic location. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;74:1087-1093

Ullman T, Croog V, Harpa N et al. Progression of flat low-grade dysplasia to advanced neoplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2003;125:1311-1319

Connell WR, Lennard-Jones JE, Williams CB, Talbot IC, Price AB, Wilkinson KH. Factors affecting the outcome of endoscopic surveillance for cancer in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 1994;107:934-944

Befrits R, Ljung T, Jaramillo E, et al. Low-grade dysplasia in extensive, long-standing inflammatory bowel disease: a follow-up study. Dis Colon Rectum 2002;45:615-620

Lynch DA, Lobo AJ, et al. Failure of colonoscopic surveillance in ulcerative colitis. Gut 1993;34:1075-1080

Bernstein CN, Shanahan F and Weinstein WM. Are we telling patients the truth about surveillance colonoscopy in ulcerative colitis? Lancet 1994;343:71-74

Blackstone MO, Riddell RH, Rogers BH and Levin, B. Dysplasia-associated lesion or mass (DALM) detected by colonoscopy in long-standing ulcerative colitis: an indication for colectomy. Gastroenterology 1981;80: 366-74

Torres C, Antonioli D and Odze RD. Polypoid dysplasia and adenomas in inflammatory bowel disease: a clinical, pathologic, and follow-up study of 89 polyps from 59 patients Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:275-284

Rubin PH, Friedman S, Harpaz N, Goldstein E, Weiser J, Schiller J, Waye JD, Present DH. Colonoscopic polypectomy in chronic colitis: conservative management after endoscopic resection of dysplastic polyps. Gastroenterology 1999;117:1295-1300

Engelsgjerd M, Farraye FA, Odze RD. Polypectomy may be adequate treatment for adenoma-like dysplastic lesions in chronic ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 1999; 117):1288-1294

Van Schaik FD, Mooiweer E, van der Have M et al. Adenomas in patients with inflammatory bowel disease are associated with an increased risk of advanced neoplasia. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:342-349

Connelly TM and Koltun WA. The surgical treatment of inflammatory bowel disease-associated dysplasia. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;7:307-22

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

MCQs

1. The only surgical resection that will excise all primary and synchronous neoplasms and prevent metachronous lesions in IBD is:

A) Total proctocolectomy

B) Total abdominal Colectomy

C) Segmental resection of the affected colon

D) None of the above

2. DALM is:

A) Dysplasia-associated lesion or mass that is readily amenable to colonoscopic removal

B) Dysplasia/adenoma luminal material that is used in chromoendoscopy to improve identification of lesions in ulcerative colitis patients

C) Dysplasia-associated lesion or mass that by definition is unable to be removed colonoscopically and mandates surgical excision

D) Dysplasia/adenoma luminal mass that frequently is diagnosed as a hyperplastic polyp on biopsy and pathology

3. Multifocal flat high-grade dysplasia discovered on surveillance colonoscopy in an otherwise healthy UC patient, suggests the need for which of the following:

A) Repeat colonoscopy/multiple every 10 cm biopsies in 6–12 months

B) Total proctocolectomy

C) Institution of ASA derivatives and repeat colonoscopy/biopsies in 6–12 months

D) Diverting ileostomy to quell inflammation and repeat colonoscopy/biopsies.

4. A 40-year-old male patient presents with a 20-year history of colitis and low-grade dysplasia on colonoscopy. The next step in diagnosis and treatment is:

A) Confirmation by second pathologist opinion and/or repeat biopsy

B) Endoscopic resection of all dysplasia

C) Repeat colonoscopy in 6 months

D) Segmental resection of all areas containing dysplasia

5. A colonic stricture in a UC patient is a concern for:

A) Impending obstruction

B) Crohn's disease

C) Carcinoma

D) All of the above

6. A large polypoid mass is discovered in an area of inflammation in a Crohn's patient. This lesion is called:

A) Low-grade dysplasia

B) A DALM

C) An ALM

D) An adenoma-like DALM

7. Risk factors for CRC in the IBD patient include:

A) PSC

B) Family history of colorectal cancer

C) Extensive colitis

D) All of the above

8. Cumulative risk of CRC in UC 30 years after diagnosis is:

A) 5 %

B) Equal to the non IBD population

C) 18 %

D) 10 %

Answers:

1) A

2) C

3) B

4) A

5) D

6) D

7) D

8) C

The Division of Colon and Rectal Surgery at Penn State College of Medicine, Hershey Penn State Medical Center is the recipient of the Carlino Fund for IBD Research

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Connelly, T.M., Koltun, W.A. The Cancer “Fear” in IBD Patients: Is It Still REAL?. J Gastrointest Surg 18, 213–218 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-013-2317-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-013-2317-z