Abstract

Introduction

Stomal varices can develop in patients with ostomy in the setting of portal hypertension. Bleeding from the stomal varices is uncommon, but the consequences can be disastrous. Haemorrhage control measures that have been described in the literature include pressure dressings, stomal revision, mucocutaneous disconnection, variceal suture ligation and sclerotherapy. These methods may only serve to temporise the stomal bleeding and have a high risk of recurrent bleed. While transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunting has been advocated as the treatment of choice in patients with underlying liver cirrhosis, histoacryl glue or coil embolisation has been successfully employed in patients who are not suitable candidates for TIPS.

Methods and Results

Direct percutaneous embolisation of the dominant varices was performed successfully under ultrasound and fluoroscopic guidance in two patients using a combination of coils and histoacryl glue.

Results

While transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunting has been advocated as the treatment of choice in patients with underlying liver cirrhosis, histoacryl glue or coil embolisation has been successfully employed in patients who are not suitable candidates for TIPS.

Conclusion

Direct percutaneous embolisation is a safe and effective treatment for stomal varices in selected patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Stomal varices are an uncommon cause of gastrointestinal haemorrhage and occur in the presence of portal hypertension. The management of bleeding from stomal varices includes simple measures such as local compression, suture ligation and sclerotherapy to more invasive methods such as stomal revision, mucocutaneous disconnection and porto-systemic shunts. We describe a safe and effective alternative in the management of bleeding stomal varices when simple local measures fail to control the haemorrhage.

Patient 1

A 57-year-old female presented with a 2-day history of dizziness and recurrent episodes of bleeding from her colostomy. Her background history included a Duke C rectal cancer with synchronous solitary liver metastases 3 years previously for which she underwent Hartmann’s procedure and adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. She developed metachronous liver metastases 12 months later for which a staged liver resection was planned. She initially underwent a left lobe metastasectomy and right portal vein embolisation; however, there was disease progression and the patient subsequently underwent only chemotherapy.

During this presentation, the patient was anaemic (haemoglobin 64 g/L) with a normal coagulation profile. The bleeding from the stoma persisted despite direct pressure and local infiltration of haemostatic agent. Subsequent endoscopic investigation via the stoma revealed peristomal portal hypertensive changes without obvious varices or source of active bleeding. Abdominal computed tomography confirmed multiple recurrent hepatic metastases with secondary portal hypertension. In addition, a large varix arising from the jejunal branch of the superior mesenteric vein was present and drained into the colostomy site (Fig. 1a).

Under ultrasound guidance, a direct percutaneous puncture of the dominant stomal varix was achieved under sterile conditions. Digital subtraction venography demonstrated hepatofugal flow within the varix towards a complex meshwork of peristomal variceal veins (Fig. 1b). A 7-cm segment of the varix was selected with a 4-French catheter and embolised with 0.035 coils initially (Fig. 1c), followed by controlled injection of histoacryl glue. Post-embolisation venography confirmed complete occlusion of the varix (Fig. 1d).

The stomal bleeding resolved immediately after the procedure and the patient had no further episodes of bleeding before her death 1 month later from the progressive metastatic disease.

Patient 2

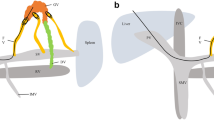

A 74-year-old female presented with recurrent episodes of bleeding from her ileal conduit secondary to a dominant stomal varix, which was a result of the underlying portal hypertension from non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (Fig. 2a). She had a background history of interstitial cystitis for which an ileal conduit urinary diversion surgery was performed 5 years ago.

Direct pressure, injection of sclerosants (phenol and almond oil), attempted banding of the stomal varices as well as commencement of β-blocker medication only served to control the stomal haemorrhage temporarily.

Once again, the dominant varix was directly accessed under ultrasound and fluoroscopic guidance via one of the dilated veins at the base of the ileal conduit. A 4-French catheter was passed to the vein draining to the superior mesenteric vein (Fig. 2b). After confirming the absence of any vital draining visceral vessels, the dominant vessel feeding the varix was embolised using a combination of coils and histoacryl glue (Fig. 2c).

At the end of the procedure, the ileostomy was visually less congested and there was no report of stomal bleed for at least 6 months.

Discussion

Peristomal varices develop when the hepatofugal flow from the high pressure portal venous system decompresses into the low pressure systemic veins of the abdominal wall via the mucocutaneous venous network surrounding the stoma site.1 This phenomenon can occur in up to 50 % of patients with enterostomies/colostomies with concurrent portal hypertension.2, 3 The risk of stomal bleeding in this setting has been estimated to be approximately 27 %.

A number of treatment options have been described in an attempt to decrease the portal pressure at the stomal site and arrest bleeding from the peristomal mucocutaneous venous network. Local therapies such as direct compression and injection of vasoconstrictive or sclerosing agents have proven to be less successful in preventing recurrent variceal bleeding from the stoma, as these temporizing techniques do not address the underlying portal hypertension and may be associated with stomal injury.1, 4, 5 While surgical revision and re-siting of the stoma, disconnection of mucocutaneous porto-systemic communications are other options but these procedures are invasive and carry high risk of postoperative morbidity in patients with portal hypertension.2, 6–8 In addition, new venous collaterals may also develop at the newly formed stomal site.9

Liver transplantation would be an ideal treatment of recurrent stomal bleed in patients with portal hypertension due to underlying liver cirrhosis.10 This option, however, was not indicated in the first patient as the nature of the liver disease was outside of the liver transplantation criteria. Transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt is an effective treatment modality in patients with stomal bleeding, but it has been associated with a recurrent bleeding rate of up to 25 %.11 This approach was not appropriate for the first patient as she had multiple liver metastases obstructing the right and left hepatic veins.12 Both liver transplantation and transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt were not appropriate in the second patient as she was elderly and had no identifiable cause for underlying liver disease.

Embolisation of bleeding stomal varices, either via the internal jugular vein or the percutaneous approach, has been successfully performed.13 While the transhepatic approach can potentially be associated with an increased risk of hepatic bleeding or injury,9, 13 direct percutaneous embolisation of the dominant stomal varix under ultrasound guidance using either glue or coils is a safe and effective technique in controlling stomal bleeding in the setting of portal hypertension. This approach is particularly useful when a single, dominant feeding varix is identified. In order to minimise the development of future varices, the ideal length of embolisation should commence from the origin of the major varix to as distally as possible, preferably the ostomy site. The benefit of using the cyanoacrylate glue at the distal end of the vessel in addition to the coils is to anchor the coils thereby preventing migration of the embolisation materials.

One of the limitations of this approach is that the patient may still develop additional varices or venous collaterals at the stomal site as the underlying cause of portal hypertension remains untreated. This could potentially lead to further stomal bleeding from the newly developed venous network surrounding the stoma. In addition, this technique relies heavily on the ability of the ultrasound to clearly visualize the feeding varix so that accurate percutaneous puncture and subsequent embolisation of the vessel can be achieved. Finally, transhepatic route would be an easier option technically if there are numerous collateral vessels to be accessed and embolised in the same setting.

In conclusion, direct percutaneous embolisation with glue and coils is a safe and effective treatment for stomal variceal bleeding in selected patients.

References

Johnson PA, Laurin J. Transjugular portosystemic shunt for treatment of bleeding stomal varices. Digestive diseases and sciences. Feb 1997;42(2):440–442.

Norton ID, Andrews JC, Kamath PS. Management of ectopic varices. Hepatology. Oct 1998;28(4):1154–1158.

Ryu RK, Nemcek AA, Jr., Chrisman HB, et al. Treatment of stomal variceal hemorrhage with TIPS: case report and review of the literature. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. Jul-Aug 2000;23(4):301–303.

Vidal V, Joly L, Perreault P, Bouchard L, Lafortune M, Pomier-Layrargues G. Usefulness of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the management of bleeding ectopic varices in cirrhotic patients. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. Mar-Apr 2006;29(2):216–219.

Medina CA, Caridi JG, Wajsman Z. Massive bleeding from ileal conduit peristomal varices: successful treatment with the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. The Journal of urology. Jan 1998;159(1):200–201.

Conte JV, Arcomano TA, Naficy MA, Holt RW. Treatment of bleeding stomal varices. Report of a case and review of the literature. Diseases of the colon and rectum. Apr 1990;33(4):308–314.

Han SG, Han KJ, Cho HG, et al. A case of successful treatment of stomal variceal bleeding with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt and coil embolization. Journal of Korean medical science. Jun 2007;22(3):583–587.

Kishimoto K, Hara A, Arita T, et al. Stomal varices: treatment by percutaneous transhepatic coil embolization. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. Nov-Dec 1999;22(6):523–525.

Naidu SG, Castle EP, Kriegshauser JS, Huettl EA. Direct percutaneous embolization of bleeding stomal varices. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. Feb 2010;33(1):201–204.

Hedaya MS, El Moghazy WM, Uemoto S. Living-related liver transplantation in patients with variceal bleeding: outcome and prognostic factors. Hepatobiliary & pancreatic diseases international: HBPD INT. Aug 2009;8(4):358–362.

Kochar N, Tripathi D, McAvoy NC, Ireland H, Redhead DN, Hayes PC (2008) Bleeding ectopic varices in cirrhosis: the role of TIPSS. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 28(3):294-303.

Alkari B, Shaath NM, El-Dhuwaib Y, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic porto-systemic shunt and variceal embolisation in the management of bleeding stomal varices. International journal of colorectal disease. Sep 2005;20(5):457–462.

Arulraj R, Mangat KS, Tripathi D. Embolization of bleeding stomal varices by direct percutaneous approach. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. Feb 2011;34 Suppl 2:S210–S213.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kwok, A.C.H., Wang, F., Maher, R. et al. The Role of Minimally Invasive Percutaneous Embolisation Technique in the Management of Bleeding Stomal Varices. J Gastrointest Surg 17, 1327–1330 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-013-2180-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-013-2180-y